Classic Human Anatomy in Motion: The Artist's Guide to the Dynamics of Figure Drawing (2015)

Chapter 4

Facial Muscles and Expressions

When learning about muscles’ influence on the surface form, the muscles of the face present the trickiest problem. This is because the various circular and straplike facial muscles are completely covered by a layer of subcutaneous tissue that usually obscures any evidence of their presence beneath the skin. This means you must approach your understanding of facial anatomy in a holistic way. Knowing approximately where the muscles attach on the cranium is helpful, but it is only one part of the picture. Bone structure, facial planes, facial features, and the overall three-dimensionality of the head and face are likewise important, as are elements such as the shape of the hair, the fleshiness (or lack thereof) of the face, wrinkles (if present), and the attitude, or psychology, that the face projects. Attitude can be conveyed by the way a head is held, the quality of the eyes, a slight hint of emotion playing across the facial features, and other subtle factors.

So why learn about the placement of facial muscles at all? The answer is that understanding facial muscles is key to understanding the movements of the face, better known as facial expressions. The study of facial muscles and their movements is essential for animators, storyboard artists, comic book artists, illustrators, and fine artists who want to achieve a sense of narrative and expressiveness within their figurative work. Understanding muscle and soft-tissue placement is also important for forensic artists who reconstruct faces from skulls found at archaeological or crime sites, helping them create lifelike likenesses of people whose faces have vanished.

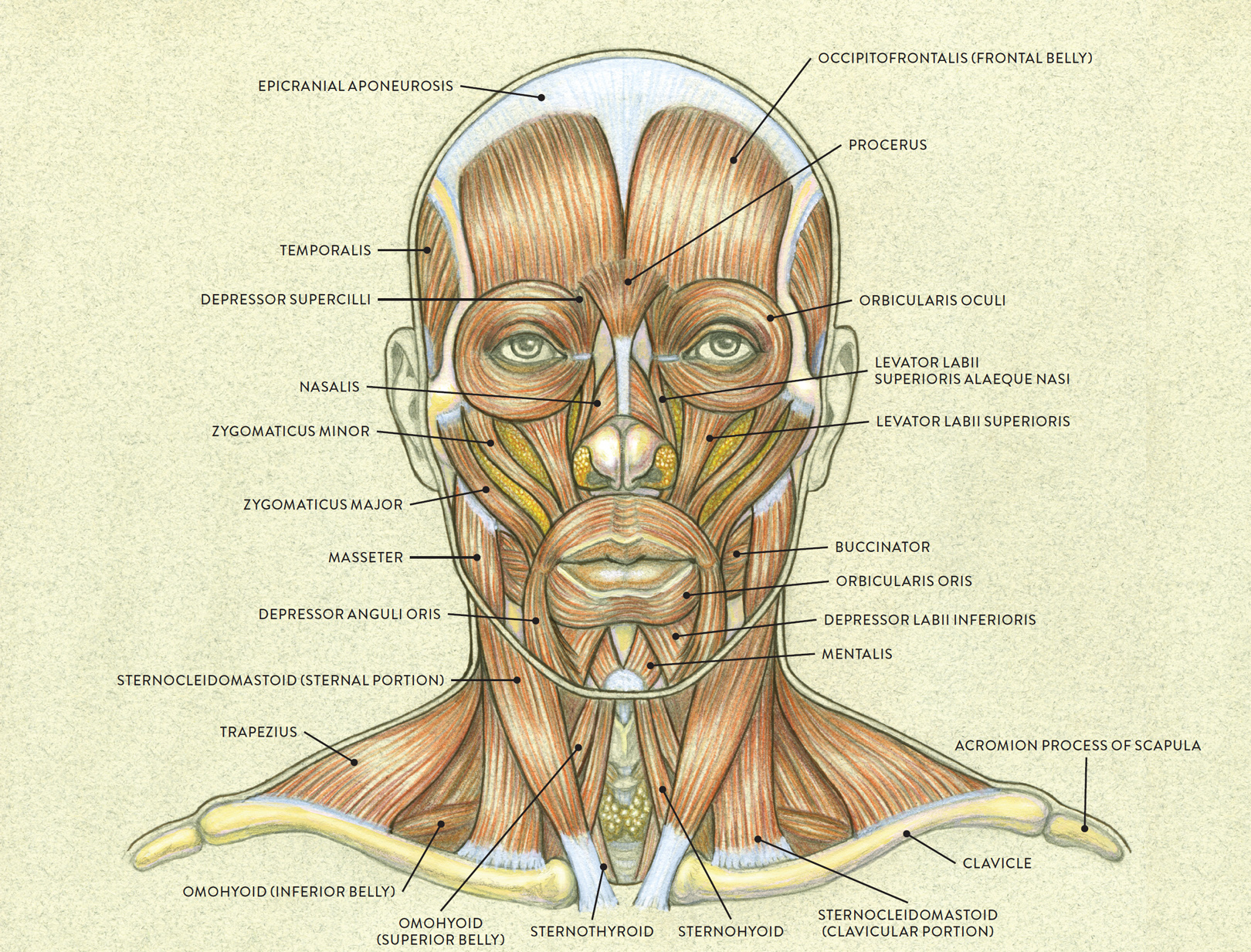

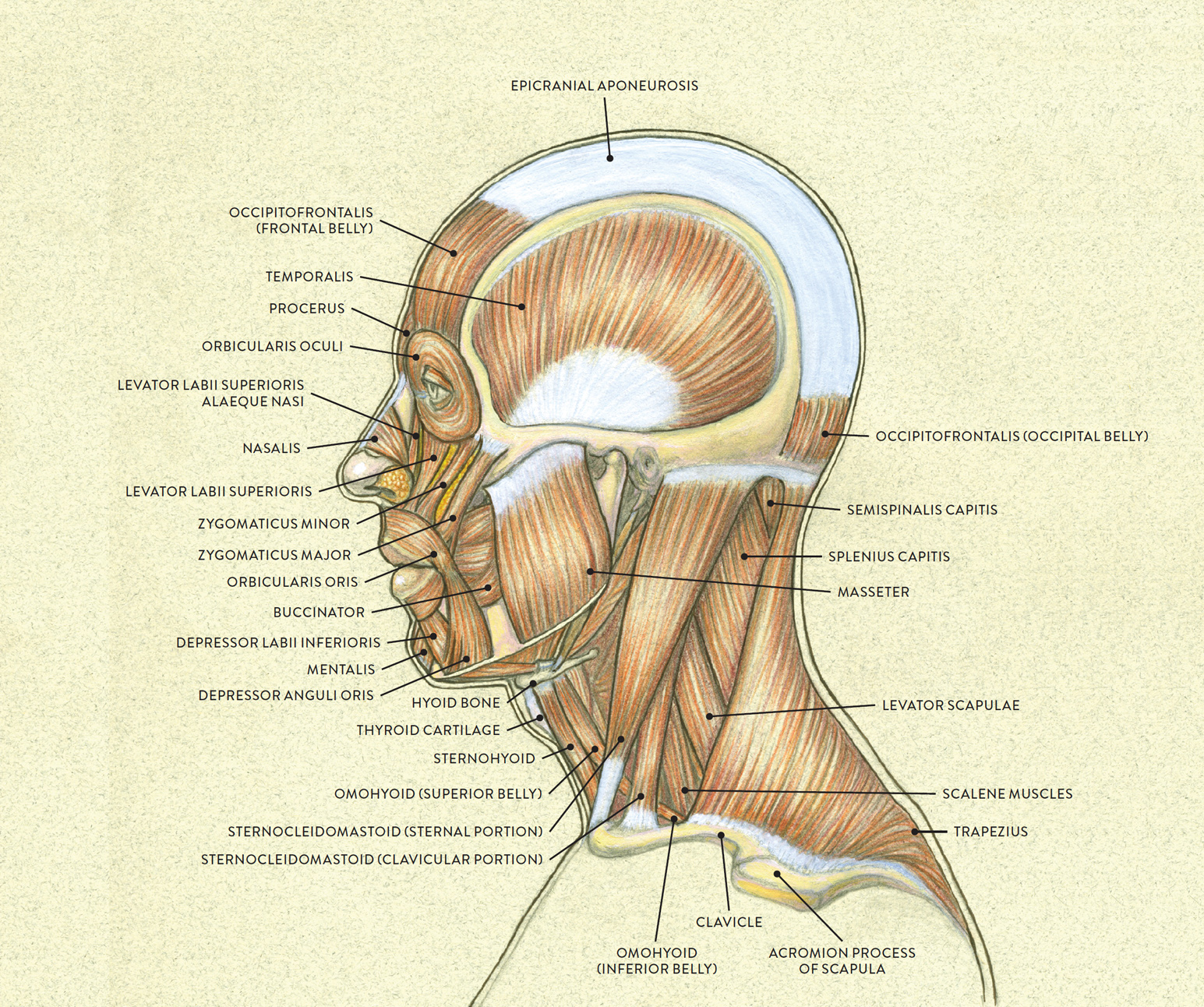

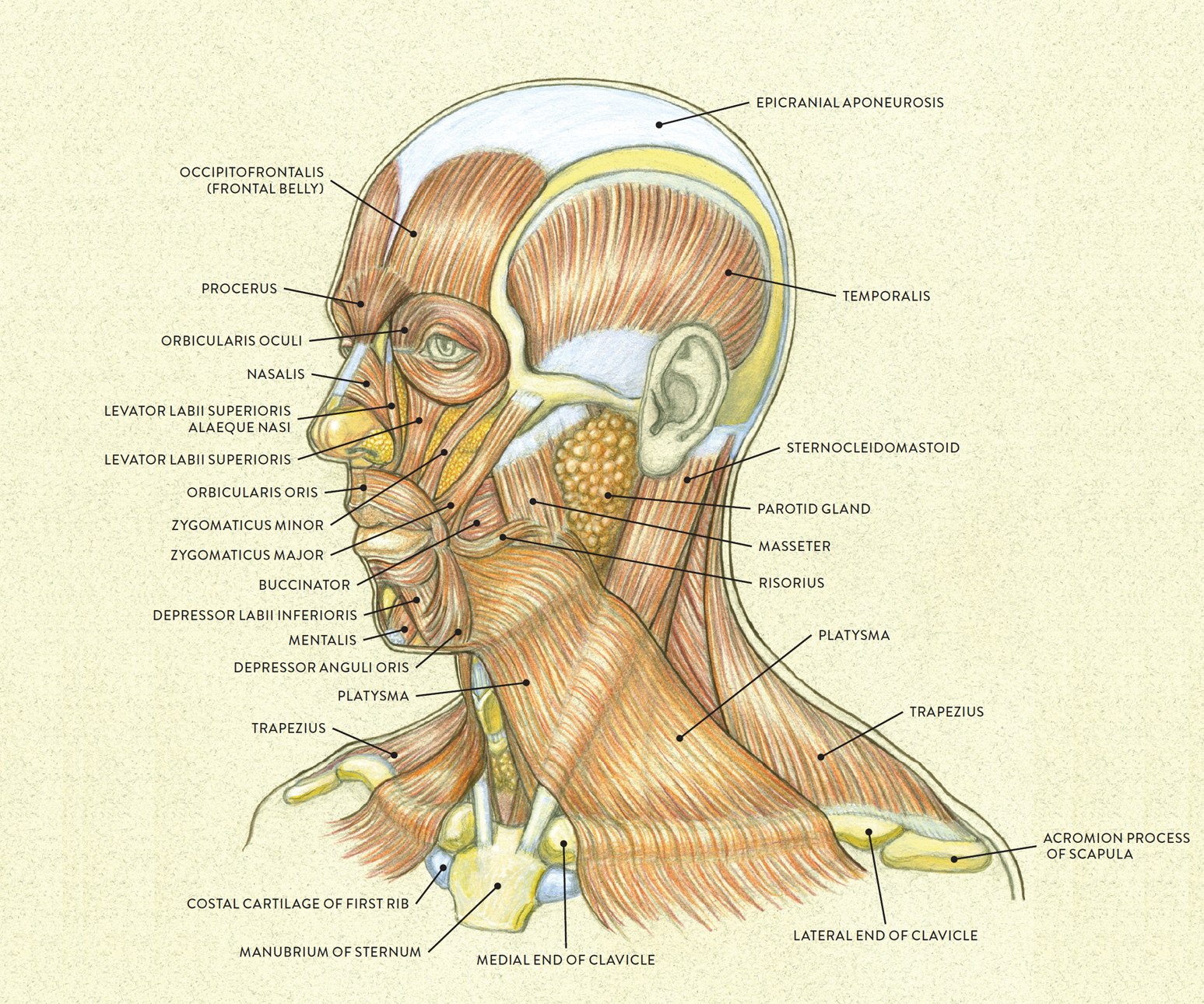

The first three drawings in this chapter depict the muscles of the face in the anterior, lateral, and three-quarter views.

MUSCLES OF THE FACE—ANTERIOR VIEW

MUSCLES OF THE FACE—LATERAL VIEW

MUSCLES OF THE FACE, WITH PLATYSMA MUSCLE—THREE-QUARTER VIEW

Facial Muscle Movement

As discussed in the previous chapter, an individual skeletal muscle generally attaches on one bone (the site of origin) and then crosses over a joint to attach on a second bone (the site of insertion). When the muscle contracts, it pulls the second bone, creating movement. While this is an extremely simplified explanation, it does help you understand the general pattern of body movement. For the most part, however, this pattern does not apply to the facial region.

The anterior portion of the skull, consisting of the facial bones, is the site of attachment for most facial muscles. Since the bones of the cranium are, with the exception of the mandible (jawbone), fused together, these bones cannot move when facial muscles contract. Facial muscles do generally originate on bone, like the skeletal muscles of the rest of the body, but instead of inserting on a different bone, they insert on soft-tissue structures. So when muscles of the face contract, they do not pull bones but rather the various soft forms of the face (eyebrows, eyelids, lips, skin), creating facial movements, or expressions.

Skin creases called expressive lines, or dynamic lines, typically occur in the vicinity of a facial expression. For example, when the muscle of the forehead (frontalis) contracts, it lifts the eyebrows upward, producing a series of horizontal creases on the forehead. On young people’s faces, the creases in the skin disappear when the muscles relax, but as people age many of these expressive lines become static lines, or permanent wrinkles, etched into the skin. When an older person makes a particular facial expression and then relaxes his or her face, the wrinkles—worry lines, laugh lines, crow’s feet, frown lines—remain present on the surface of the skin.

Facial Muscle Groups

In what follows, I group the facial muscles according to the region of the face that they influence most significantly: the forehead muscle group, the orbital muscle group (of the eye region), the nasal muscle group, and the oral muscle group. The muscles that lift the upper lip (oral muscles—upper group) and those that depress the lower lip (oral muscles—lower group) are dealt with separately. The locations of these muscle groups are shown in the following drawing.

FACIAL MUSCLE GROUPS

I will also be introducing the muscles of the jaw and one muscle of the neck, the platysma, that is importantly involved in facial expressions.

Names of Facial Muscles

The names of facial muscles provide clues to their location, function, or size. Knowing the meanings of these terms helps you avoid confusing one facial muscle with another, similarly named muscle:

· Labii pertains to the lips.

· Nasalis and nasi pertain to the nose.

· Orbicularis pertains to a circular or orblike form.

· Oculi pertains to the eye.

· Oris pertains to the mouth.

· Supercilii means “above the eyebrow.”

· Inferioris means “below,” or “lower.”

· Superioris means “above,” or “upper.”

· Levator indicates that a body part is moved in an upward direction.

· Depressor indicates that a body part is moved in a downward direction.

· Major means “greater.”

· Minor means “lesser.”

The Forehead Muscle Group

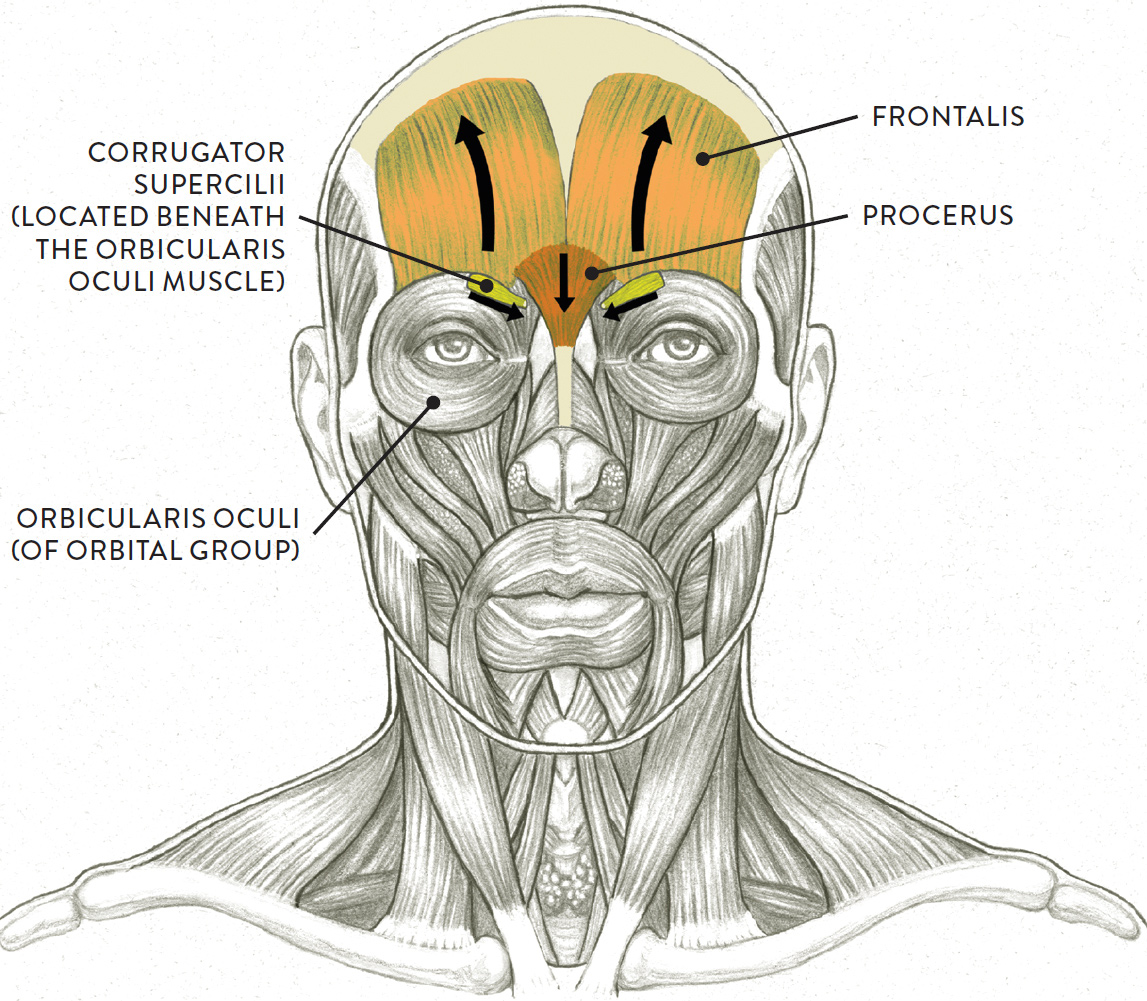

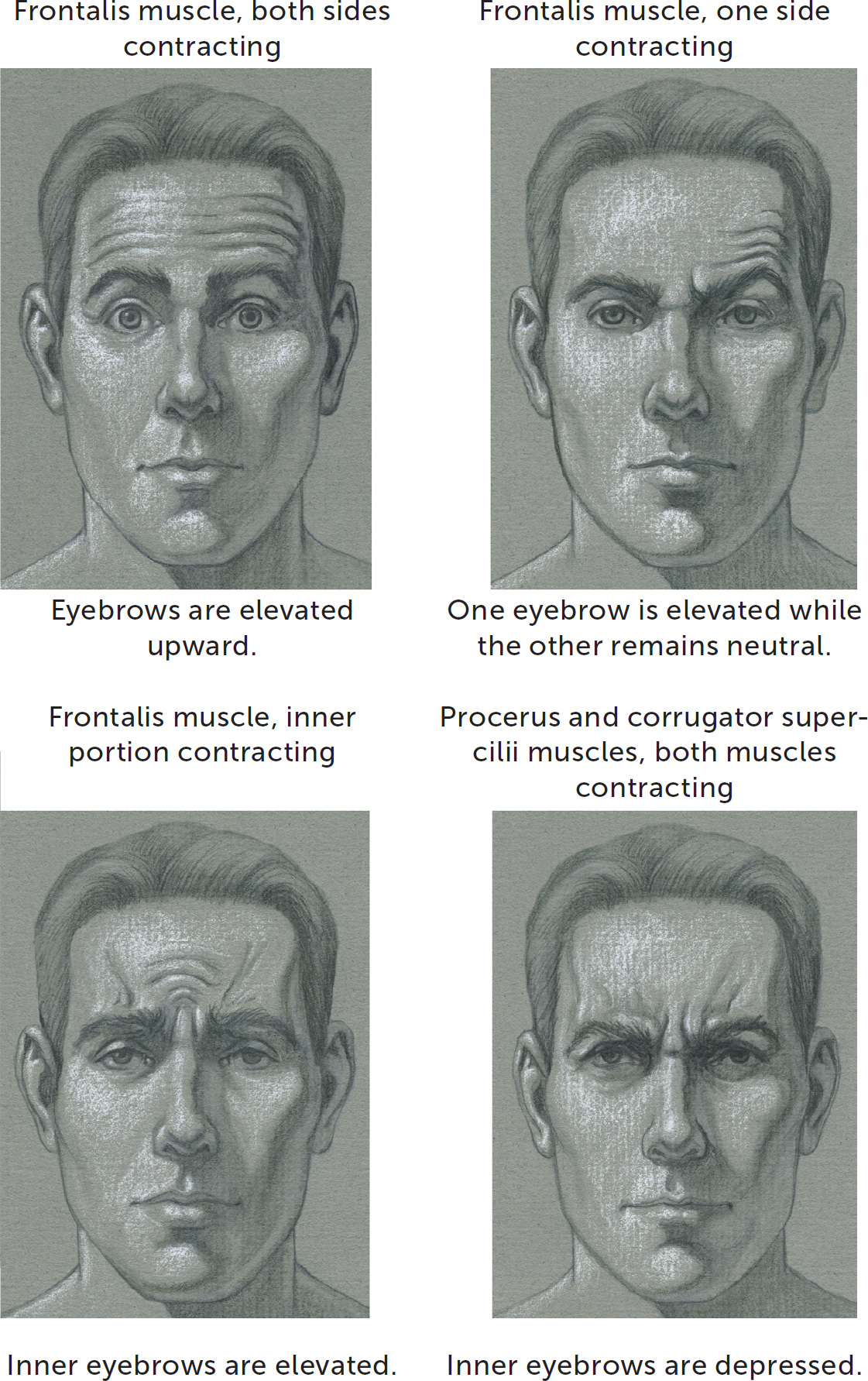

The forehead muscle group, located on the frontal bone of the cranium, consists of the frontalis, procerus, and corrugator supercilii muscles. These are the muscles that move the eyebrows and the skin of the forehead. Muscles of the forehead group and their associated expressions are shown in the following drawings.

FOREHEAD MUSCLE GROUP

Arrows indicate direction of muscular contraction.

FOREHEAD MUSCLE GROUP—FOUR STUDIES

The frontalis (pron., frun-TAY-liss or frun-TAL-iss) is a thin muscle occupying the forehead region of the cranium. It is divided into two sections, one on either side of the midline of the head. It is actually the frontal portion (or belly) of the occipitofrontalis muscle, which has a large, thin aponeurosis (the epicranial aponeurosis) that wraps tightly over the top of the cranium, like a skullcap; the occipital belly of this muscle is at the back of the cranium. The origin of the frontalis is near the hairline on the frontal bone. The frontalis inserts into the skin and subcutaneous tissue of the forehead near the eyebrows. The fibers of this muscle also interweave somewhat with the fibers of the orbicularis oculi and procerus muscles.

When the frontalis as a whole contracts, it lifts both eyebrows, producing a series of horizontal wrinkles across the forehead region. This action occurs in expressions of surprise, disbelief, and curiosity as well as in a silent acknowledgment of recognition.

When only one side of the frontalis contracts, it lifts one eyebrow while the other remains more or less stationary. Over the lifted eyebrow, a series of wrinkles curve on top of each other, like ripples. This action occurs in expressions of bemusement, amused distrust, or skepticism.

When just the inner portion of the frontalis contracts, with the rest of the muscle remaining in a normal state, it lifts the inner ends of the eyebrows, producing vertical and curving horizontal wrinkles in the central portion of the forehead. It can also create a curved horseshoe wrinkle above the root of the nose. This action occurs in expressions of sadness, sorrow, grief, and worry.

The corrugator supercilii (pron., KOR-uh-GATE- or soo-per-SIL-ee-eye or KOR-ah-gay-tor soo-per-SIL-lee-ee) are two small muscles, each positioned at an slight angle beneath the orbicularis oculi muscle of the orbital group (see this page). Its origin is on the inner end of the brow ridge of the frontal bone, and it inserts into the forehead skin over the middle of the eyebrow.

When the corrugator supercilii contracts, it lowers the inner ends of the eyebrows, producing skin wrinkles in a vertical direction on the forehead near the root of the nose. This expression is associated with anger, and these creases are called vertical glabellar furrows or frown lines. Other expressions include intense concentration, concern, disapproval, annoyance, and a state of confusion. The corrugator supercilii works in tandem with the procerus muscle in the expression commonly called “knitting the eyebrows.” On some faces you can see the bulging shape of the corrugator supercilii muscle when it is contracting.

The procerus (pron., pro-SAIR-us, pro-SEE-rus, or pro-SIR-us) is a small fan-shaped muscle positioned in the lower central region of the forehead. Its origin is on the bridge of the nose (the nasal bone and upper portion of the lateral nasal cartilage) and fascia, and it inserts into the skin of the lower region of the forehead between the eyebrows.

When the procerus contracts, it depresses the inner ends of the eyebrows, producing a horizontal skin crease at the root of the nose. It can also produce a vertical skin wrinkle on the inner end of each eyebrow. This muscle, along with the two corrugator supercilii muscles and the two depressor supercilii muscles of the orbital group (see this page), produces a frowning action of the eyebrows. It is activated in expressions of anger, disdain, disapproval, annoyance, and intense concentration.

The Orbital Muscle Group

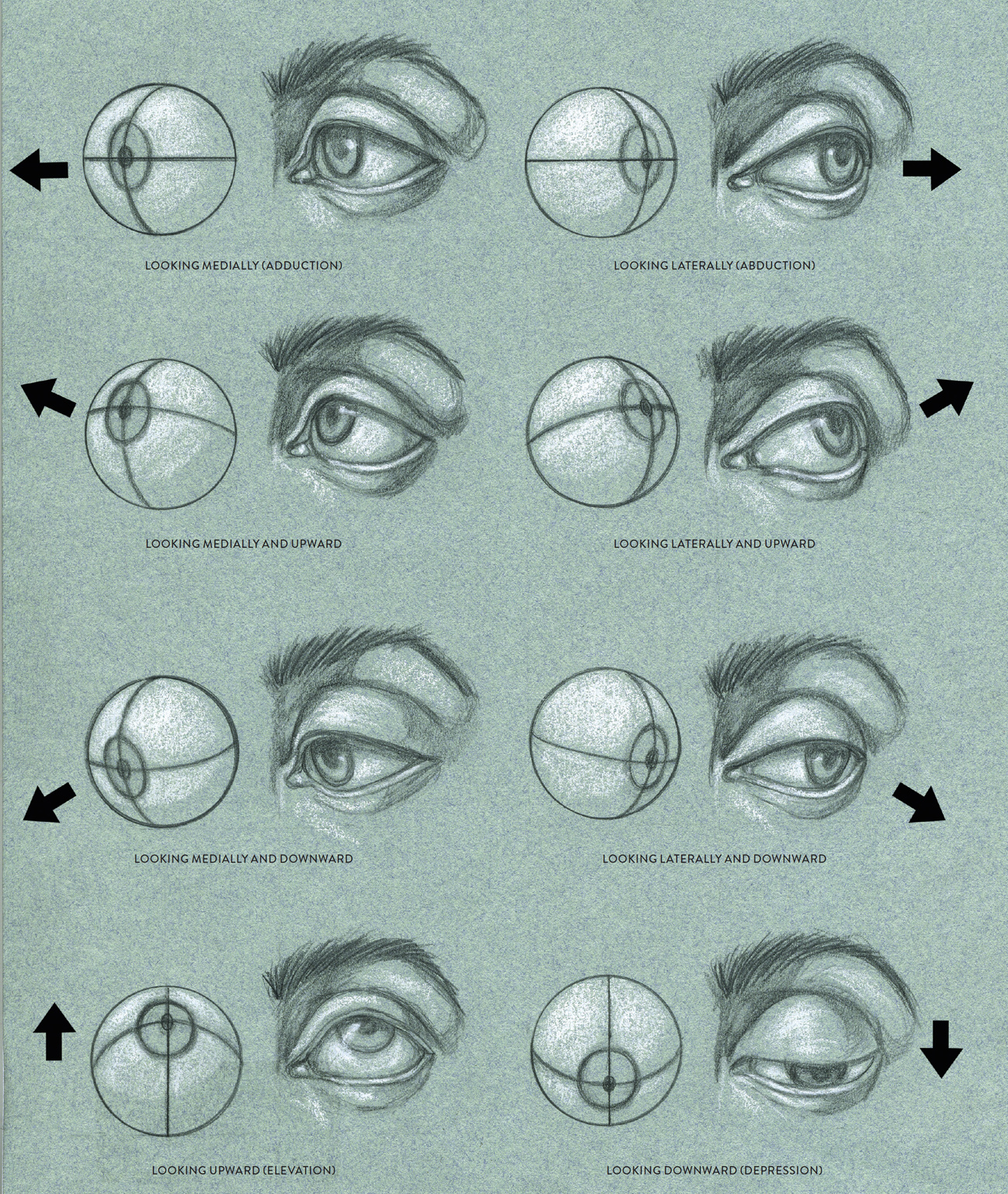

The ball of the eye is positioned within its eye socket (orbital cavity) in a cushion of orbital fat. The orbital muscle group includes the orbicularis oculi and depressor supercilii muscles, which participate in moving the eyelids and portions of the eyebrows (see this page). Additionally, there are several elongated strips of muscle called the extrinsic eye muscles, or extra-ocular muscles, that originate at the back of the orbital cavity and other locations within the eye socket and that insert on the ball of the eye. These muscles, shown in the drawing below, move the eye in various directions, causing it to directly look up (elevation), directly look down (depression), and look to the left and right (abduction and adduction). They also assist in moving the eye to look upward medially or laterally, and to look downward medially or laterally. None of the extrinsic muscles can be seen on the surface, but I include them here because of their essential role in eye movement.

EXTRINSIC EYE MUSCLES

Left eye, lateral view

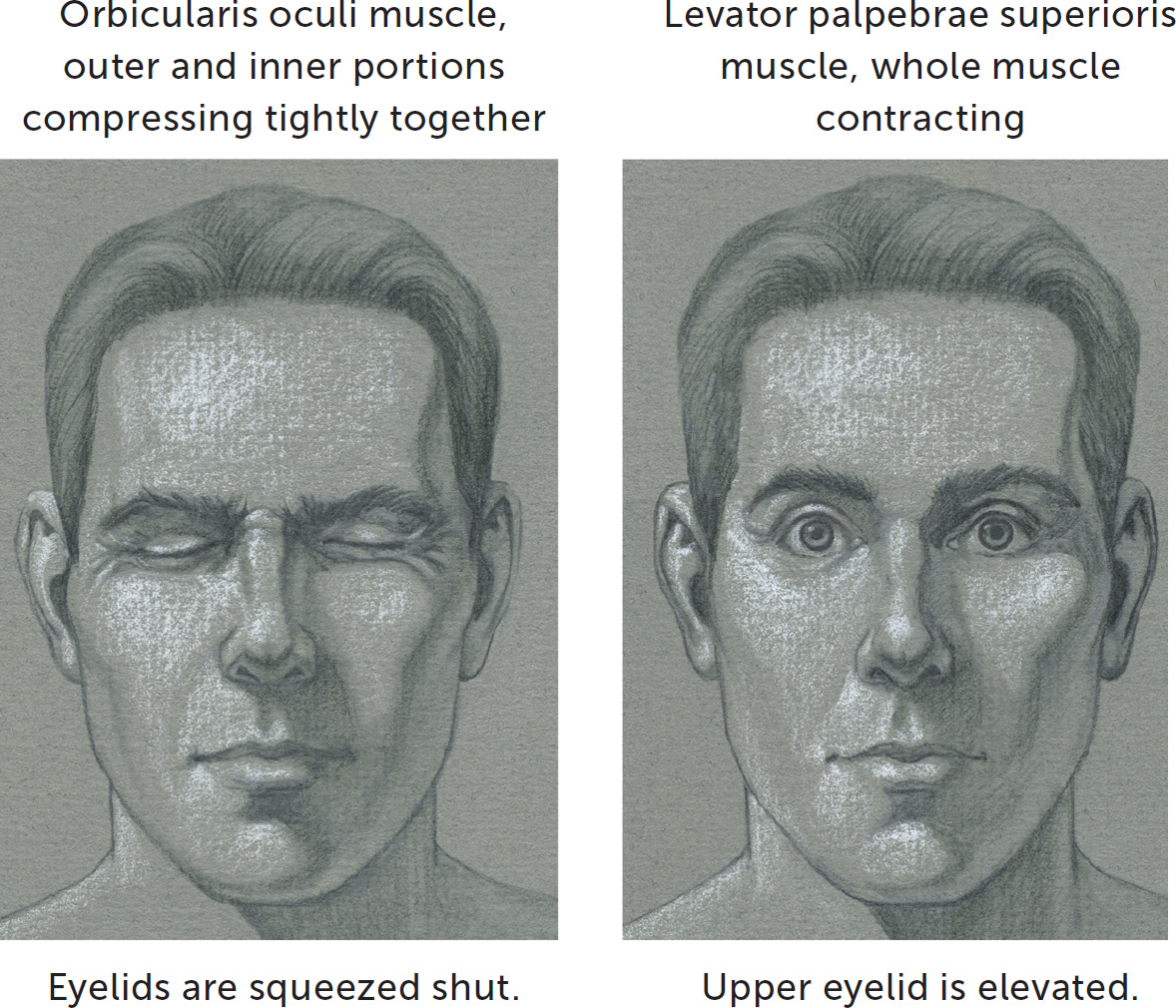

One of the extrinsic eye muscles moves the upper eyelid but does not participate in moving the eyeball. This is the levator palpebrae superioris (LEV-uh-tor PAL-pa-bree soo-PEER-ee-or-iss), a small, slender muscle in the orbital cavity that attaches directly into the skin of the upper eyelid rather than on the eyeball. While it is the orbicularis oculi muscle (see this page) that closes or squeezes the upper lid, the levator palpebrae superioris is responsible for lifting the upper lid in an exaggerated manner—the action colloquially known as the “deer in the headlights” stare or the “bug-eyed” look. The full contraction of the muscle reveals the white of the eye above the upper lid and can be seen in expressions of terror, shock, and astonishment. More moderate contractions cause an intense stare or look of surprise or disbelief. This muscle is not seen on the surface form.

The drawing Movement of the Eyeball, shows the movement capability of the eyeball enabled by the extrinsic eye muscles. The placement of the iris, which is the round colored disk of the eyeball, immediately tells us the direction the eyes are looking in.

MOVEMENT OF THE EYEBALL

Left eye, anterior view

Becoming aware of the placement and shape of the iris on the ball of the eye will help you portray the eyes more convincingly. If the eyes are looking straight ahead, the iris is a full circle, but partly overlapped by the upper lid. When the eyes look directly upward or downward, the iris retains its circular shape, but even more of it is covered by the eyelids. When the eyes look off to either side, the iris becomes an ellipse overlapped by the eyelids.

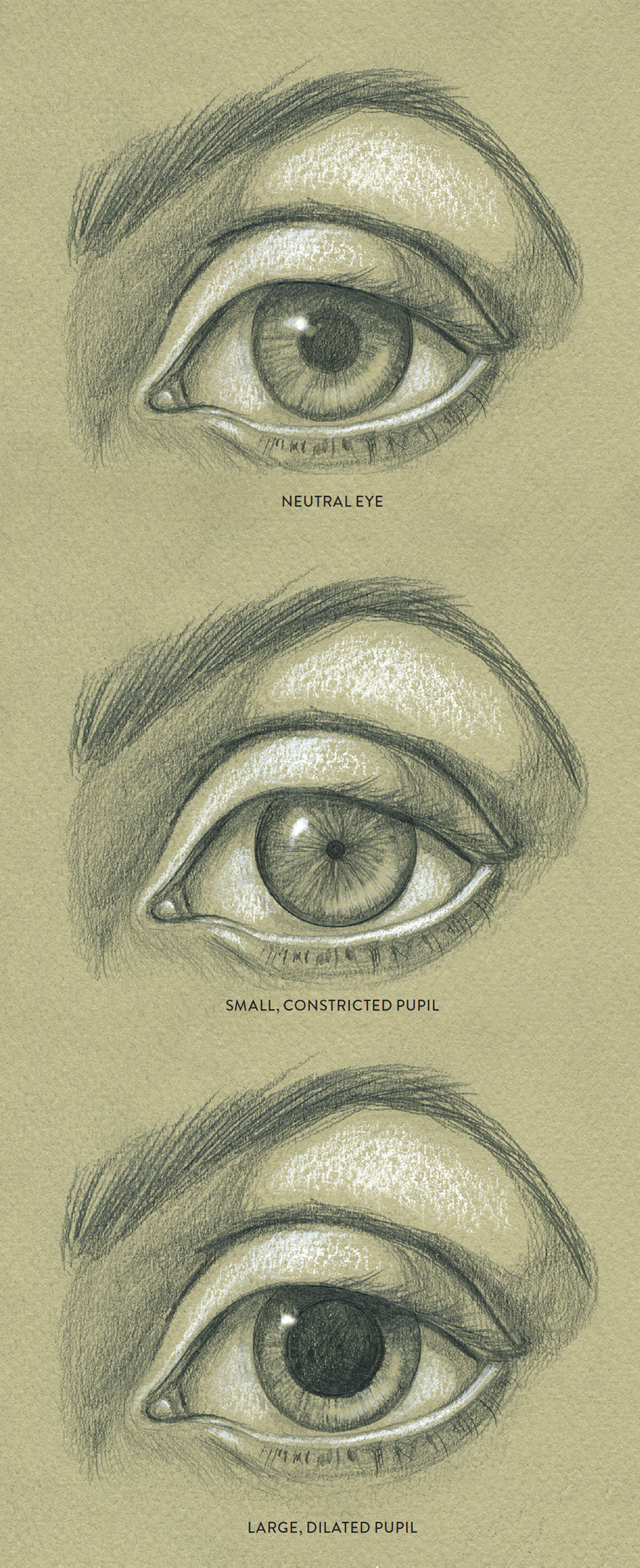

The Muscles of the Iris

When the facial muscles surrounding the eye region are activated, the eyes can communicate a variety of expressions. But even in an otherwise neutral face with no contraction of facial muscles, the eyes still have the potential of conveying expression or emotion. This is possible because of the dilation and constriction of the pupil in the center of the iris. The iris is a circular disk whose color varies among people, ranging from deep browns to hazel, green, and various shades of gray and blue. Light enters the eye through the pupil, and the iris contains two muscles that expand and contract the pupil, allowing more or less light to pass through. These muscles, which are classified as smooth muscles (not skeletal muscles), are the circular muscle of the iris and the radial muscle of the iris. When the circular muscle contracts, it reduces the size of the pupil; when the radial muscle contracts, it dilates the pupil. These muscles cannot contract at the same time.

The size of the pupils can itself convey emotion. For instance, if you depict the pupils as tiny black pin-size holes, the eyes will have extremely intense or even creepy look. Overly enlarged pupils can produce the dreamy, romantic “doe-eyed” look sometimes called “bedroom eyes.” The drawing Constriction and Dilation of the Pupil, shows three views of the left eye, each with a different size pupil. The dilation or constriction of the pupils can also work in concert with the contraction of facial muscles in the region of the eye to produce expressions. For example, if the eyebrows are lifted high, the upper lid is drooping, and the pupils are overly enlarged, the face will look sleepy or intoxicated. When the eyebrows are depressed downward and the pupils are black small holes, the facial expression can indicate rage.

CONSTRICTION AND DILATION OF THE PUPIL

Left eye, anterior view showing different size pupils

Even highlights in the eye can indicate emotion. In expressions of positive emotions, the eyes can have a sparkling look, and placing a bright highlight in one eye can communicate joy, mirth, or amusement. (Downplay the highlight in the other eye to avoid giving the eyes a sentimental quality.) In expressions of despondency and melancholy, the eyes lose their luster, so downplay or eliminate the highlights when trying to convey those moods. In expressions of grief and sorrow, tears may well up in the eyes, and these drops of fluid will have their own small highlights.

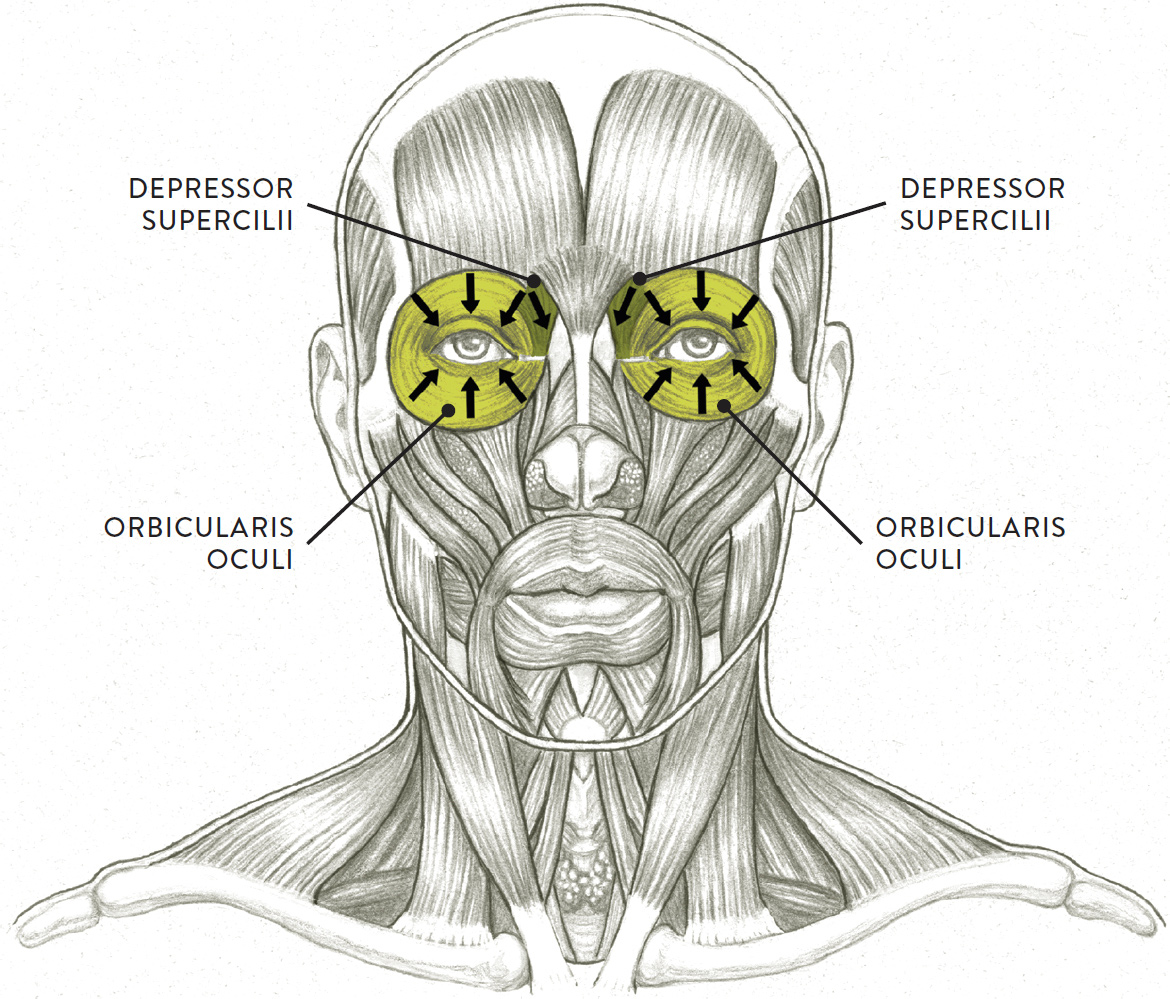

The Orbicularis Oculi and Depressor Supercilii

The orbicularis oculi and the depressor supercilii muscles are positioned on the front portion of the orbits (eye sockets), as shown in the next drawing. These muscles move the eyelids and participate in moving the eyebrows.

ORBICULARIS OCULI AND DEPRESSOR SUPERCILII

Arrows indicate direction of muscular contraction.

The orbicularis oculi (pron., or-BICK-yoo-LAR-iss OCK-yoo-lie or or-BICK-kyoo-LAIR-riss OCK-yoo-lee) is the circular muscle of the eye, positioned over the front portion of the orbit. Its basic shape is round or orblike, hence the name orbicularis. This muscle has two main sections: The outer section, called the orbital portion, surrounds the outer eye socket, while an inner portion, called the palpebral portion, lies within the eyelids.

When the inner (palpebral) portion of the orbicularis oculi contracts, it usually causes a subtle action, such as gently closing the eyelids. If the outer portion contracts with some intensity, then the lids are squeezed shut and a series of radiating skin creases—commonly called “crow’s feet”—appears at the outer corner of the eye. An even more intense contraction can create other skin creases near the root of the nose and below the lower eyelid. Depending on the degree of contraction, the orbicularis oculi also produces the actions of blinking, winking, and squinting.

Blinking is a very subtle action of the eyelids. Natural blinking is an involuntary movement of the lids (the “blink reflex”) that bathes the eyeball with fluid from the tear ducts, preventing it from drying out and clearing the eye of dust particles. While this eye movement may seem unimportant, blinking can make an animated figure seem far more natural and alive, especially when the character is not talking or showing any facial expression. Rapid, more intense blinking can also be seen in expressions of disbelief, bewilderment, and astonishment, or might indicate that a person is telling a fib. A “fluttering” of the upper lids is seen when someone is enamored or charmed.

Winking is a stronger, more intentional action than blinking. In winking, the lids of one eye are rapidly squeezed together (just once), while the other eye remains relaxed. This action can indicate that someone is “in the know” about a particular thing, but it can also be an affectionate gesture, much like throwing a small visual “kiss” to another person. In animated figures, these subtle actions can speak volumes in the absence of any dialogue.

Squinting occurs when the face is reacting to an external threat or force (wind, blinding light, physical impact) or when someone is experiencing an internal force of some intensity (sneezing, coughing, crying). More subtle squinting, in which the lower eyelid overlaps the lower portion of the iris, can be seen in expressions of skepticism, distrust, hatred, or disgust.

The depressor supercilii (pron., dee-PRESS- or soo-per-SIL-ee-eye or dee-PREH-sor soo-per-SIL-lee-ee) is actually part of the orbicularis oculi (although some anatomists consider it a separate muscle). Its fanlike fibers radiate upward from the inner portion of the orbicularis oculi near the root of the nose, interweaving with parts of the frontalis and procerus muscles of the forehead. When the depressor supercilii contracts, it assists the corrugator supercilii and procerus muscles in lowering the inner eyebrows, causing some minor skin creases on the side of the root of the nose.

The following studies shows how the eyelids move when certain orbital muscles contract on an otherwise neutral face.

ORBITAL MUSCLE GROUP—TWO STUDIES

The Nasal Muscle Group

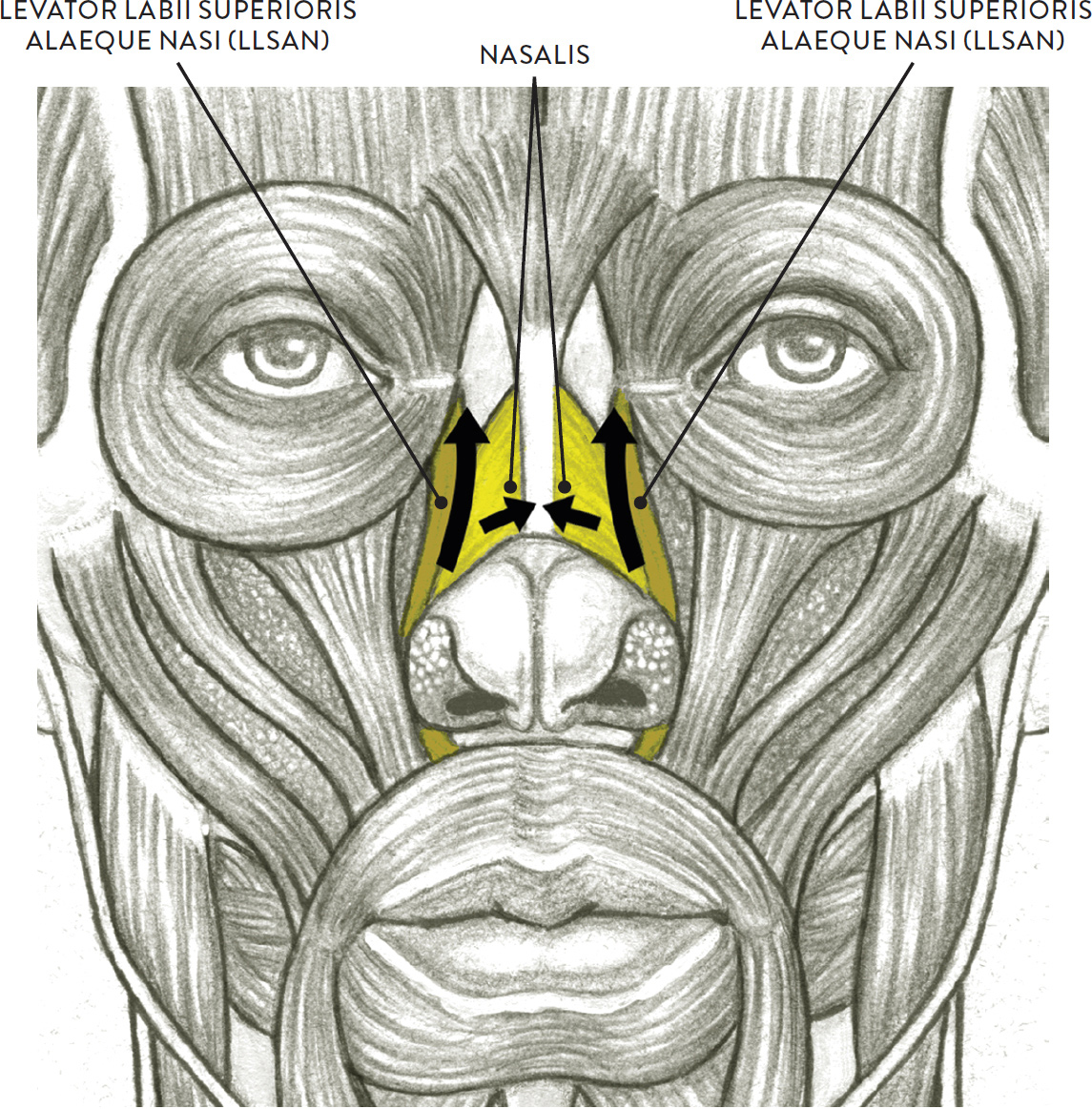

The two main muscles of the nasal region are the nasalis and the levator labii superioris alaeque nasi, shown in the following drawing. The actions of these muscles are somewhat subtle, slightly moving the wings of the nose and skin around the nose.

NASAL MUSCLE GROUP

Arrows indicate direction of muscular contraction.

The nasalis (pron., nay-ZAL-iss or nay-ZAY-liss) consists of two triangular muscles positioned on both sides of the nose and joined by a fibrous strip (aponeurosis) on the bridge. Each muscle has two portions: the transverse portion and the alar portion. Both portions begin on the lower part of the maxilla (upper jaw). The transverse portions insert into the aponeurosis on the bridge of the nose, while the alar portions insert into the alar cartilages of the nose. When the nasalis muscles contract, they produce an action that is noticeable only on close inspection, lowering and compressing the wings of the nose and slightly lowering the tip of the nose.

The levator labii superioris alaeque nasi muscles (pron., LEV-uh-tor LAY-bee-eye soo-PEER-ee-OR-iss uh-LEE-quee NAYZ-eye), or LLSAN muscles, are two elongated muscular strips positioned along either side of the nose. Each begins on the upper part of the maxilla (upper jaw), near the nasal bone, and then inserts into the wing of the nose, the skin of the nasolabial furrow (the smile crease near the wings of the nose), and the skin of the upper lip. When both LLSAN muscles contract, they lift up the wings of the nose (slightly dilating the nostrils), and the central upper lip. This action produces small wrinkles along the bridge and side of nose, commonly termed “crinkling the nose”—an expression of disgust or revulsion.

The next drawing shows how the wings of the nose elevate and wrinkles appear near the nose when certain muscles of the nasal group contract.

NASAL MUSCLE GROUP—STUDY OF A FACE

Levator labili superioris alaeque nasi, whole muscle contracting with slight contraction of the procerus muscle

Wings of the nose are elevated, causing wrinkles on the skin.

The Oral Muscle Group

Several muscles affect the lips and mouth. The main muscle is the orbicularis oris, which contains the structure of the lips. Muscles located above the orbicularis oris, collectively referred to as the oral muscles–upper group, pull the upper lip upward. Muscles located below the orbicularis oris, referred to as the oral muscles–lower group, pull the lower lip downward. A horizontal muscle called the buccinator pulls the outside corners of the mouth horizontally.

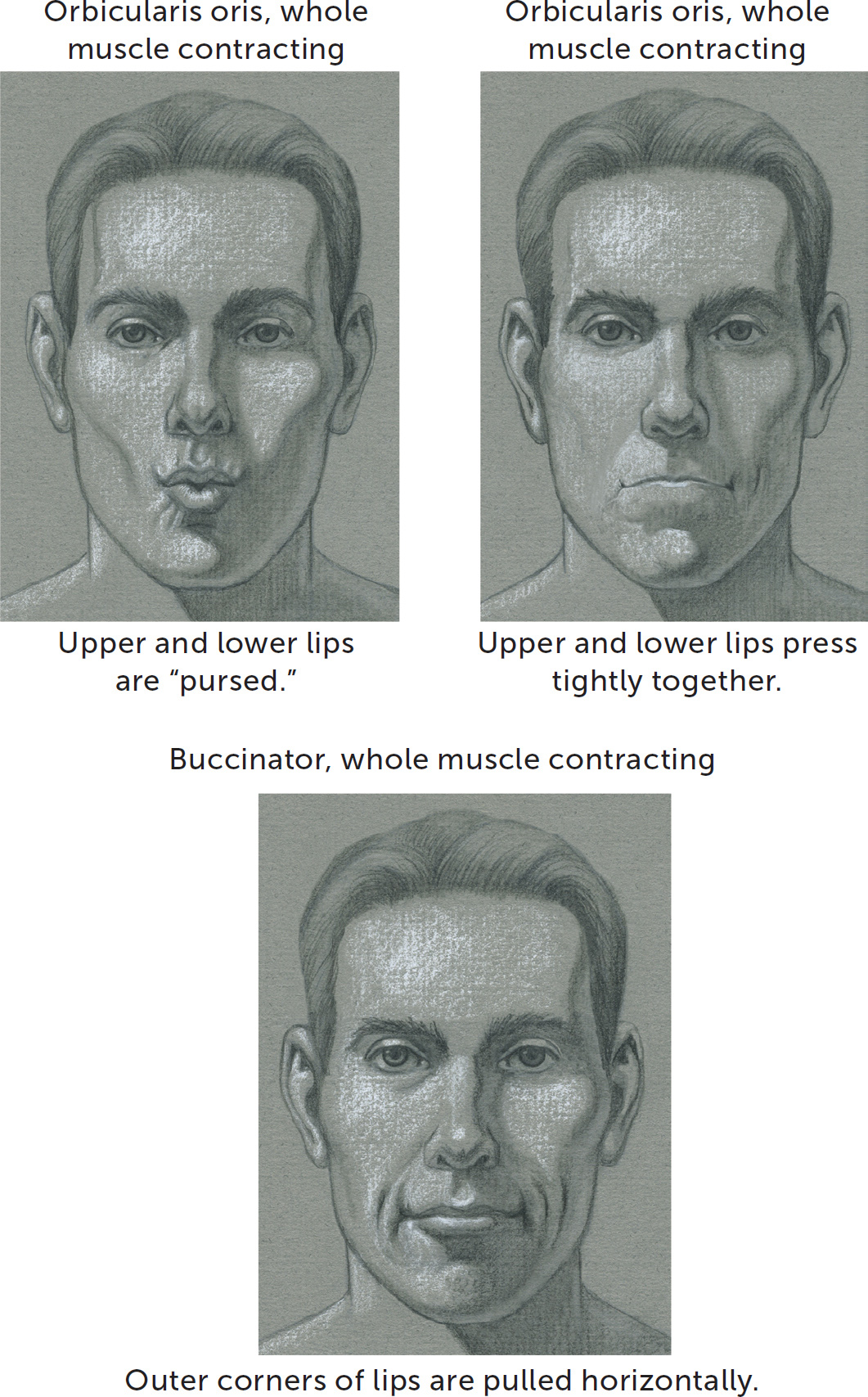

The Orbicularis Oris and Buccinator Muscles

To keep things simple, let’s start by looking at the basic oral muscle group, consisting of the orbicularis oris and buccinator muscles, shown in the following drawing.

ORBICULARIS ORIS AND BUCCINATOR

Arrows indicate direction of muscular contraction.

The term orbicularis oris (pron., or-BICK-yoo-LAR-iss OR-iss or or-BICK-kyoo-LAIR-riss OR-iss) means “the circular muscle of the mouth,” and the structure of this muscle is in some ways very similar to the structure of the orbicularis oculi, the circular muscle of the eye. It is a very complex facial muscle, mainly because it serves as a foundation for various muscular straps attaching into its outer borders.

The orbicularis oris has two portions: the outer circular portion and the form of the lips. The lips change their shape when the overall orbicularis oris and surrounding muscles contract in various degrees of intensity. The upper and lower lips are covered by skin on the outside and mucous membrane on the inside.

The muscle begins on the maxilla and mandible (upper and lower jaws) as well as on the muscle fibers of other facial muscles and the skin and fascia around the lips. It inserts into the two outer corners of the mouth (the angles of the mouth), helping to create the small mounds that are formed by many muscle attachments of surrounding muscles. The term for each mound is modiolus (pron., moe-DIE-oh-lus), meaning “hub of a wheel.”

When the orbicularis oris contracts moderately it gently closes the lips. When it contracts more intensely it compresses the upper and lower lips tightly against each other. This action can be seen in the expressions of determination, disappointment, doubt, restraint, and concentration.

The muscle also contributes to the action of protruding the lips in a small but thick circular shape. This action is sometimes called the “pursing of the lips” because the lips are drawn together like a purse with drawstrings, with skin creases radiating outward from the lips and crossing over the boundaries of the lips. The lips purse in whistling and in kissing, and the action is one element in the expression of moderate surprise. The muscle also assists in articulation in speech and in mastication (chewing).

The buccinator (pron., BUCK-sin-NAY-tor) is a flat horizontal muscle that forms the muscular wall of the cheek. The muscle originates from the maxilla and mandible near the first and second molars of both bones. It inserts into the outer perimeter of the orbicularis oris as well as the outside corner of the mouth with a series of crisscrossing muscular fibers that help create the fibrous mound of the modiolus. When the buccinator contracts, it compresses the cheeks and pulls the lips tightly across the teeth, creating dimples in the skin around the outside corners of the mouth. This action occurs in smirking and in expressions of sarcasm and contempt. Along with the orbicularis oris, the buccinator is activated when musicians play brass or woodwind instruments, hence the nickname “trumpeter’s muscle.”

The following group of facial studies shows how the mouth moves when certain oral muscles contract on an otherwise neutral face.

ORAL MUSCLE GROUP—THREE STUDIES

The Oral Muscles—Upper Group

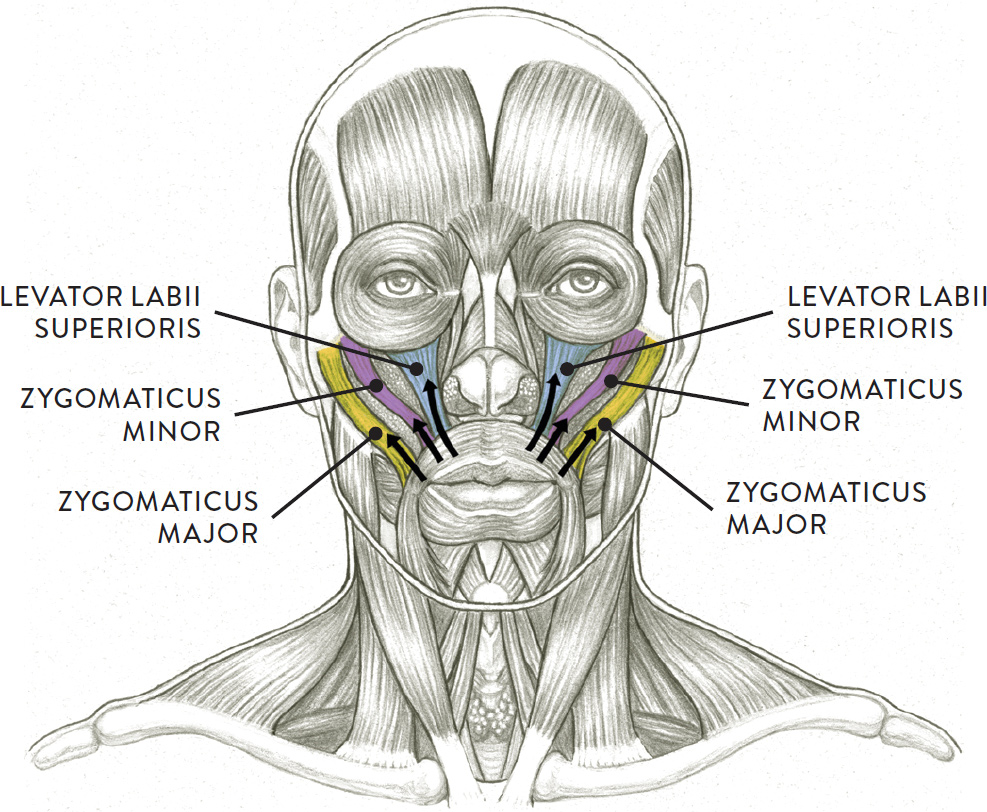

The upper group of oral muscles, located above the orbicularis oris, elevates the upper lip. The group consists of the levator labii superioris, zygomaticus minor, and zygomaticus major, all shown in the next drawing.

ORAL MUSCLES—UPPER GROUP

Arrows indicate direction of muscular contraction.

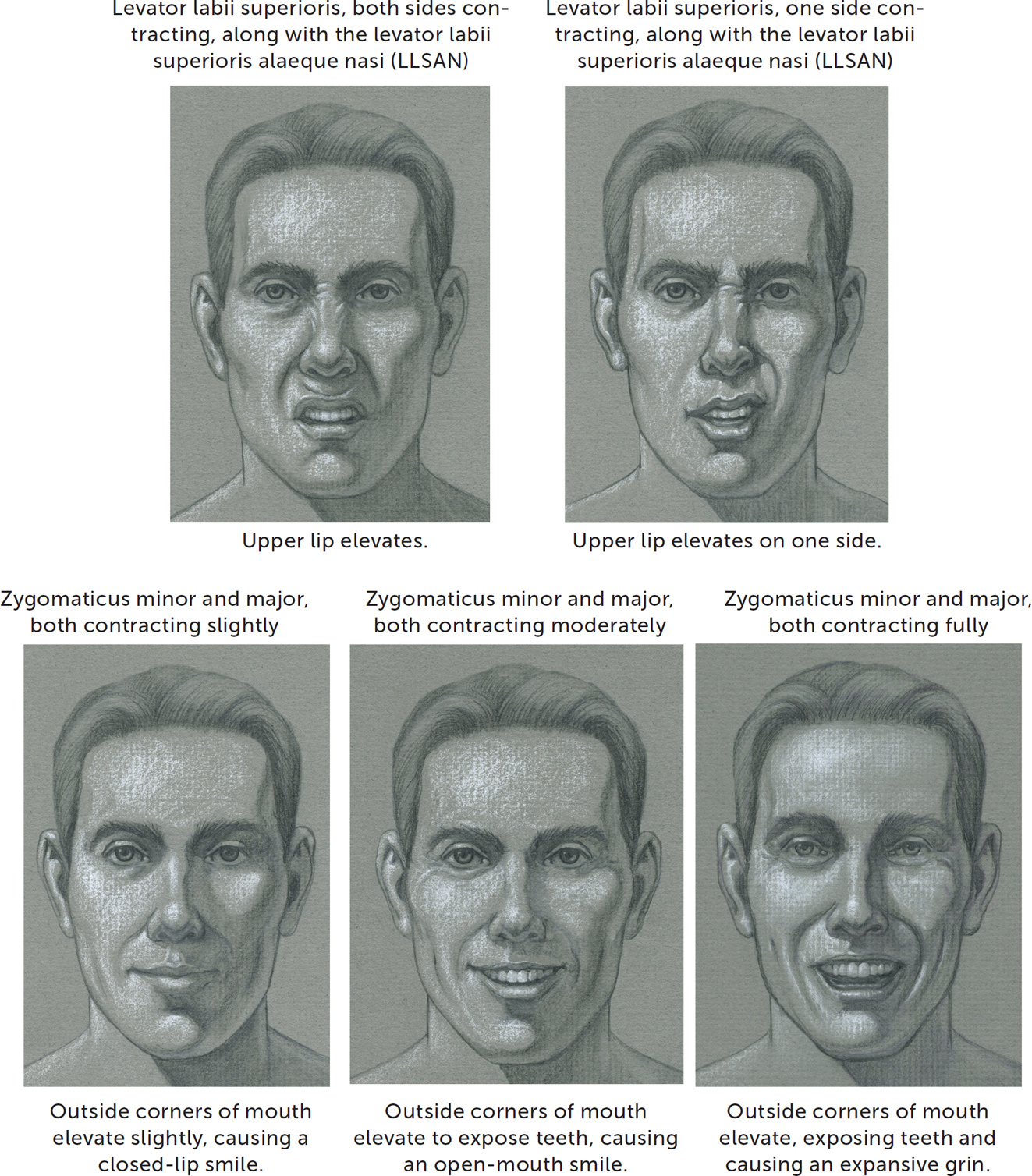

The levator labii superioris (pron., LEV-uh-tor LAY-bee-eye soo-PEER-ee-OR-iss or leh-VAH-tor lay-bee-eye soo-PEER-ee-or-iss) is a quadrilaterally shaped muscle positioned on either side of the nose. Its origin is on the lower border of the eye socket, on the zygomatic and maxilla bones. It inserts into the skin and upper lip, which is part of the orbicularis oris muscle. When the levator labii superioris contracts, it lifts the upper lip, creating a squared-arch shape and exposing the upper teeth. A crescent-shaped skin fold occurs in the philtrum region, and the crease of the nasolabial fold deepens. Expressions include contempt, disgust, and disdain. When only one side of this muscle contracts, with the other side remaining relaxed, the upper lip is pulled up on one side, giving the face a snarling or sneering expression. A subtle version of this expression is colloquially known as the “Elvis sneer.”

The zygomaticus minor (pron., zigh-go-MAT-ick-us MY-nor) is a slender muscle positioned near the zygomaticus major. The muscle begins on the frontal portion of the zygomatic bone (cheekbone) and inserts into the skin of the upper lip. When the zygomaticus minor contracts it pulls on the upper lip and the nasolabial fold.

The zygomaticus major (pron., zigh-go-MAT-ick-us MAY-jur) is a long muscular strip positioned close to the zygomaticus minor. The muscle begins on the lateral aspect of the zygomatic bone (cheekbone) and inserts into each outer corner of the mouth (modiolus). While the muscle itself is usually not seen on the surface, it does help define the transition from the front plane of the face to the side plane of the face.

The zygomaticus major is commonly called the “smile muscle” because when it contracts it pulls on the outer corners of the mouth, producing a smile. Depending on the intensity of the contraction, many variations can occur, from subtle smiles to wide-open grins. This muscle is also activated during laughter.

The group of facial studies opposite shows how the upper lip and corners of the mouth move when muscles of the upper group of oral muscles contract on an otherwise neutral face.

ORAL MUSCLES, UPPER GROUP—FIVE STUDIES

The Oral Muscles—Lower Group

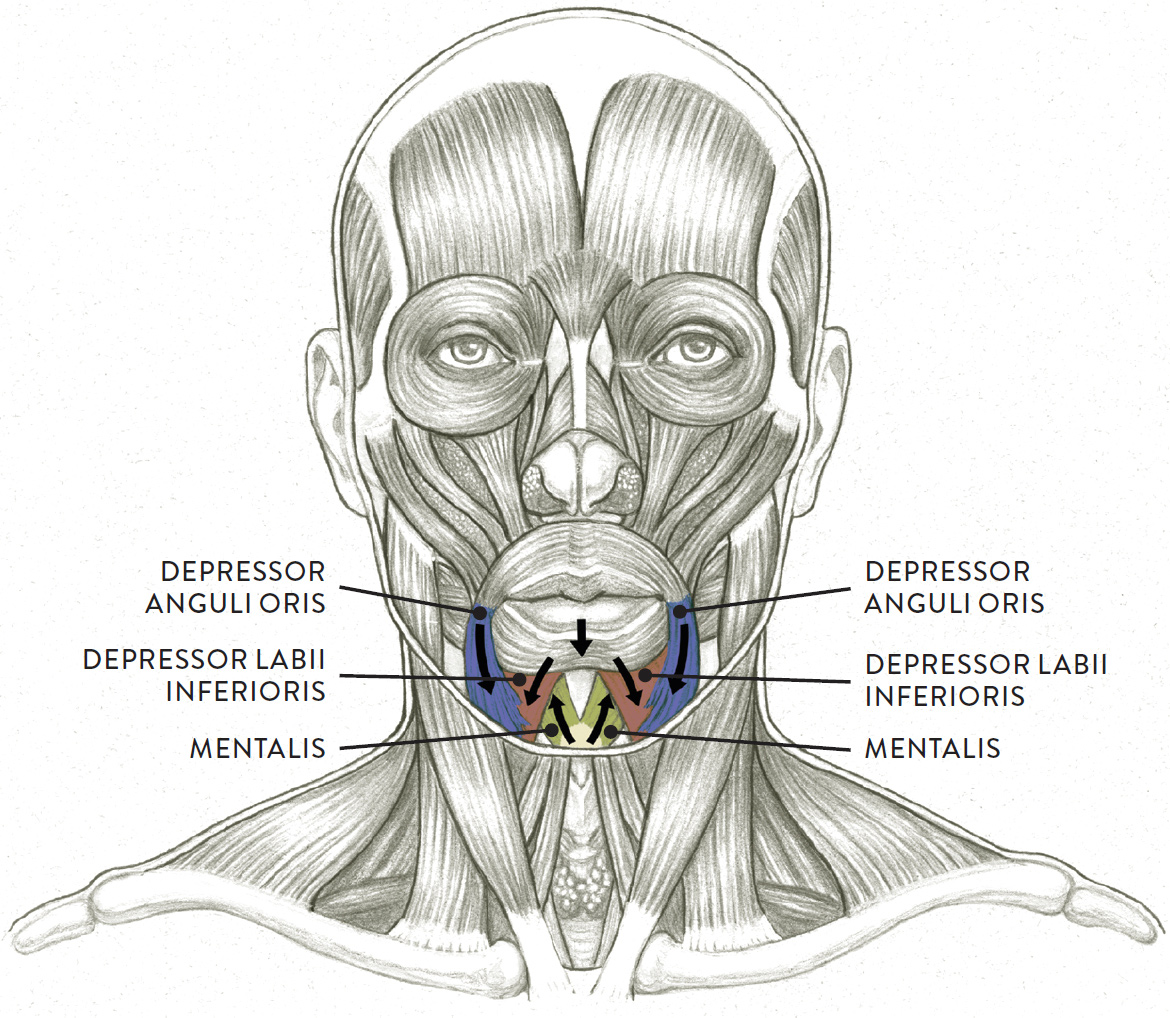

The lower group of oral muscles, located below the orbicularis oris, depress (lower) the lower lip. The muscles of this group, shown on the drawing, are the depressor anguli oris, depressor labii inferioris, and the mentalis.

ORAL MUSCLES—LOWER GROUP

Arrows indicate direction of muscular contraction.

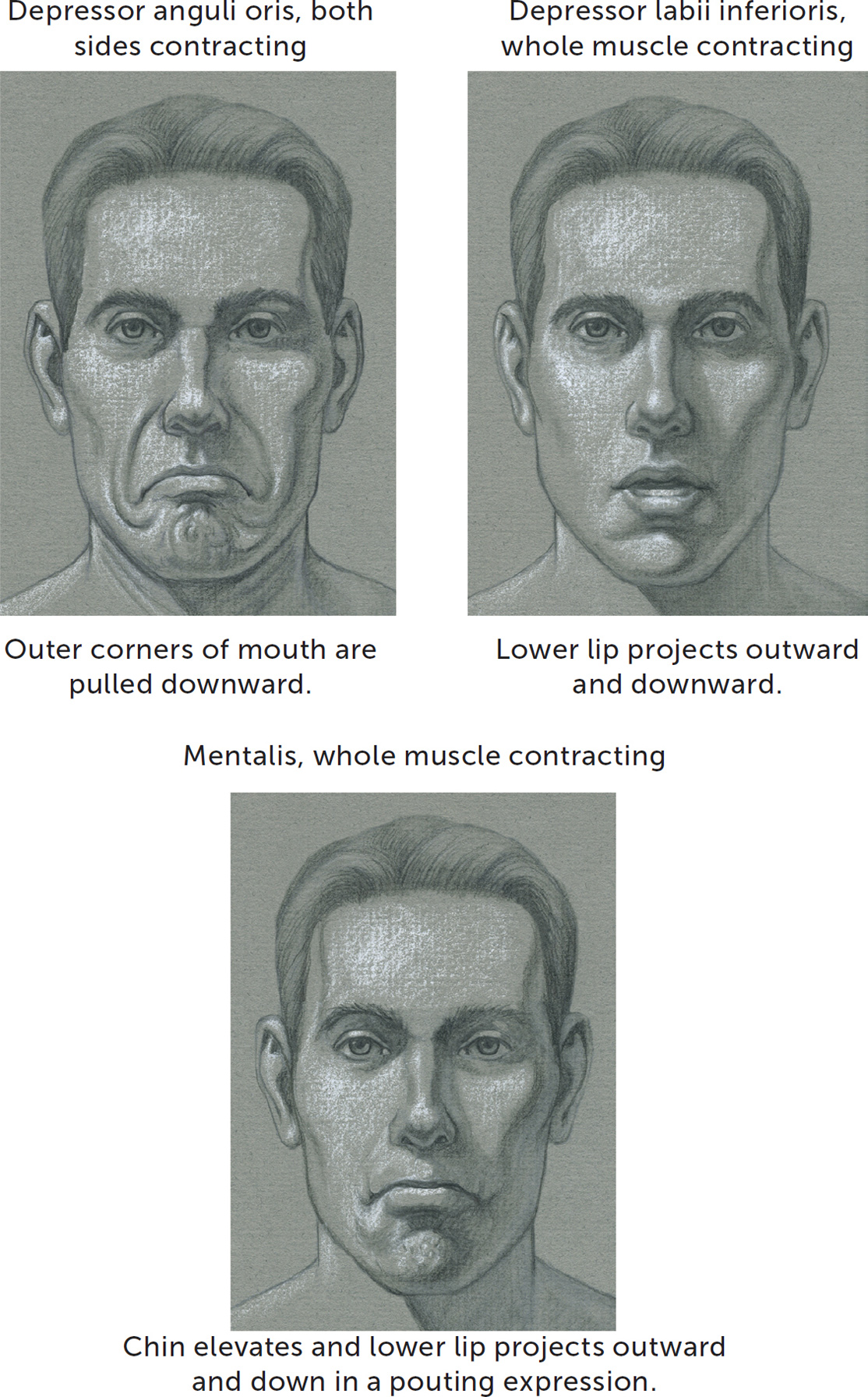

The depressor anguli oris (pron., dee-PRESS-or- ANG-yoo-lie OR-iss or dee-PREH-sor AN-gyoo-lee OR-iss) is a triangularly shaped muscle that begins on the body of the mandible near the lower border of the jaw and inserts into the skin and the orbicularis oris at the modiolus. When the depressor anguli oris muscles contract they draw the outer corners of the mouth downward, causing some downward-curving folds to appear around the outer corners of the mouth. Associated expressions include sadness, sorrow, and disappointment. A more intense contraction of this muscle, along with the contraction of the platysma muscle (see this page) will produce a grimace or a look of horror.

The depressor labii inferioris (pron., dee-PRESS- or LAY-bee-eye in-FEAR-ee-OR-iss) is a quadrilaterally shaped muscle on either side of the chin region. The muscle begins on the body of the mandible and inserts into the skin of the lower lip and the lower border of the orbicularis muscle. When the depressor labii inferioris muscles contract, they help draw the lower lip downward, slightly exposing the lower teeth. The action of this muscle is seen mostly in speech and other vocalizations.

The mentalis (pron., men-TAL-iss or men-TAY-iss) is a paired V-shaped muscle located in the chin region. It begins on the mandible, below the lower incisor teeth, and inserts into the skin of the chin. When the mentalis muscle contracts it pulls the skin of the chin upward, pushing the lower lip upward and outward in a “pouting” configuration. Many small dimples are seen in the skin of the chin. Depending on what is occurring in the rest of the face, the expression associated with this action can be one of defiance, anger, doubt, sadness, or determination.

The next group of facial studies shows how the lower lip moves when the lower group of oral muscles contract on an otherwise neutral face.

ORAL MUSCLES, LOWER GROUP—THREE STUDIES

Facial Expressions

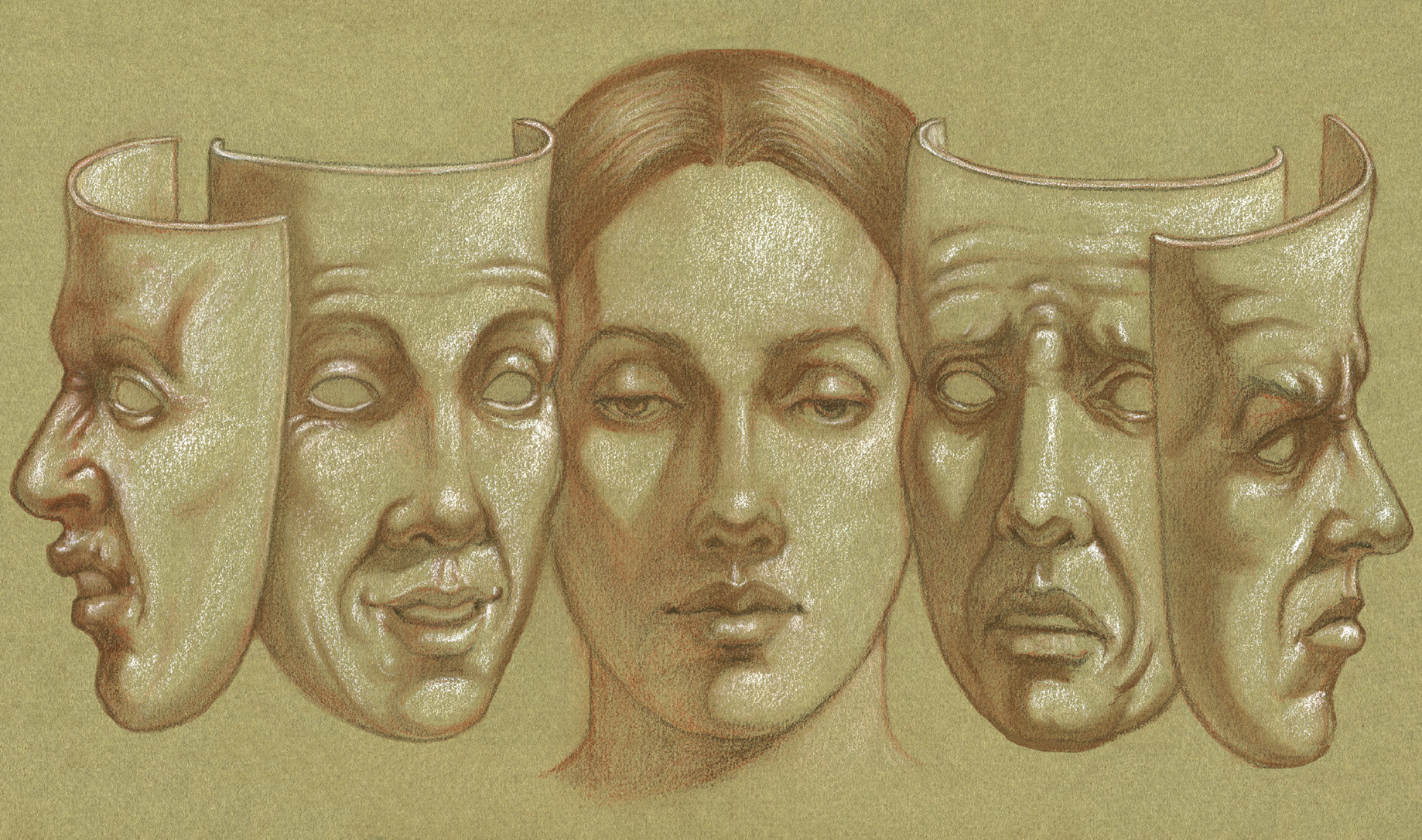

The human face is capable of thousands of expressions, ranging from minimal, barely perceptible movements, such as a slight twitching at the corner of the mouth, to full-blown muscular contractions as seen on the face during a hysterical fit of laughter. The masks in the following study present just a few.

MASKS OF DIFFERENT FACIAL EXPRESSIONS

Sanguine and brown pastel pencils and white chalk on toned paper.

Knowing the basic mechanics of facial expressions can give your figurative work a more natural quality and enable you to depict even the subtlest movement in the facial forms, such as the slight arching of one eyebrow. Granted, some artists—especially “classical” artists, both ancient and contemporary—prefer not to incorporate facial expressions in their figures, purposely keeping the faces devoid of any emotion. But for artists who want to include facial movement in their work, the study of facial expressions is both fascinating and challenging.

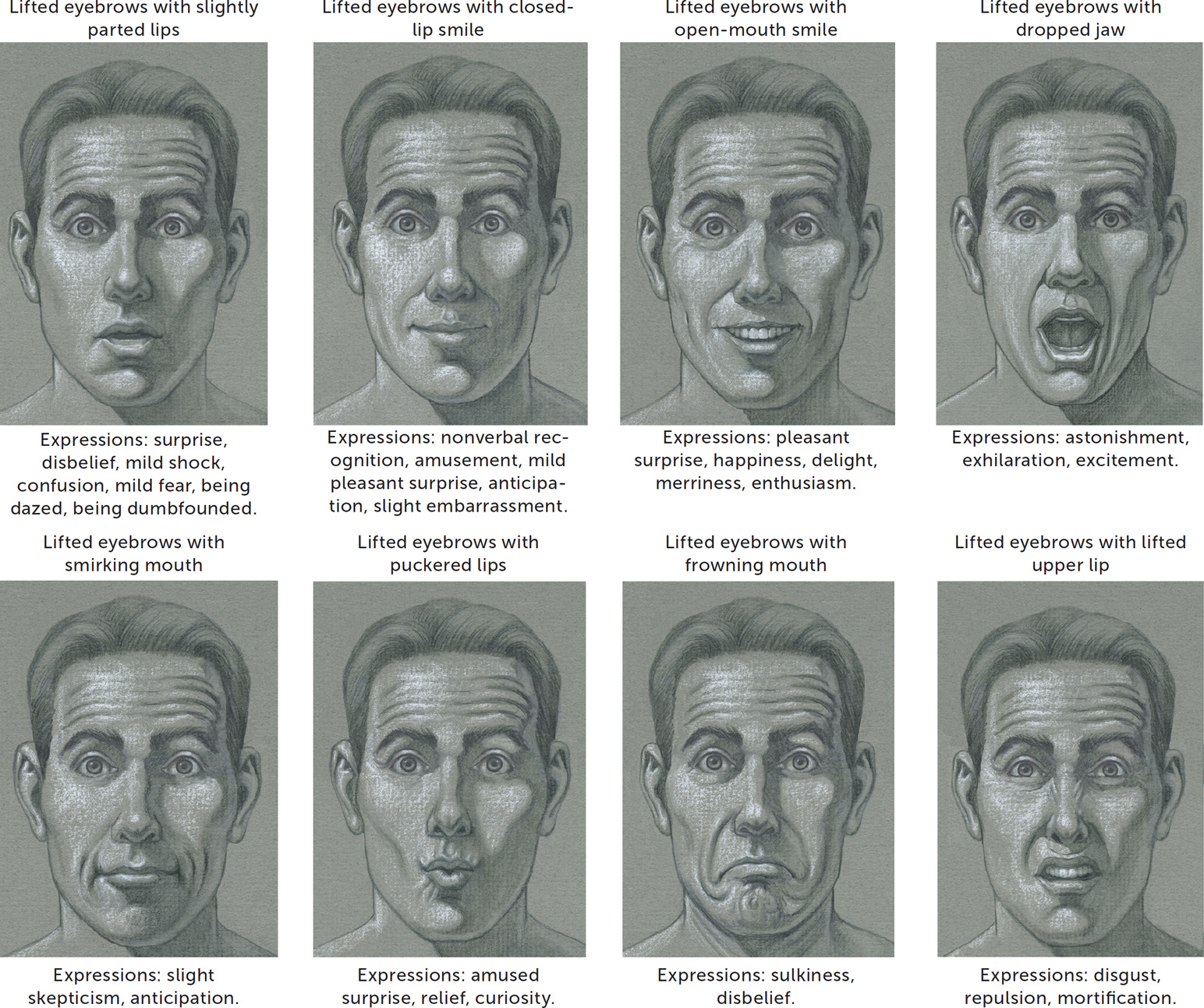

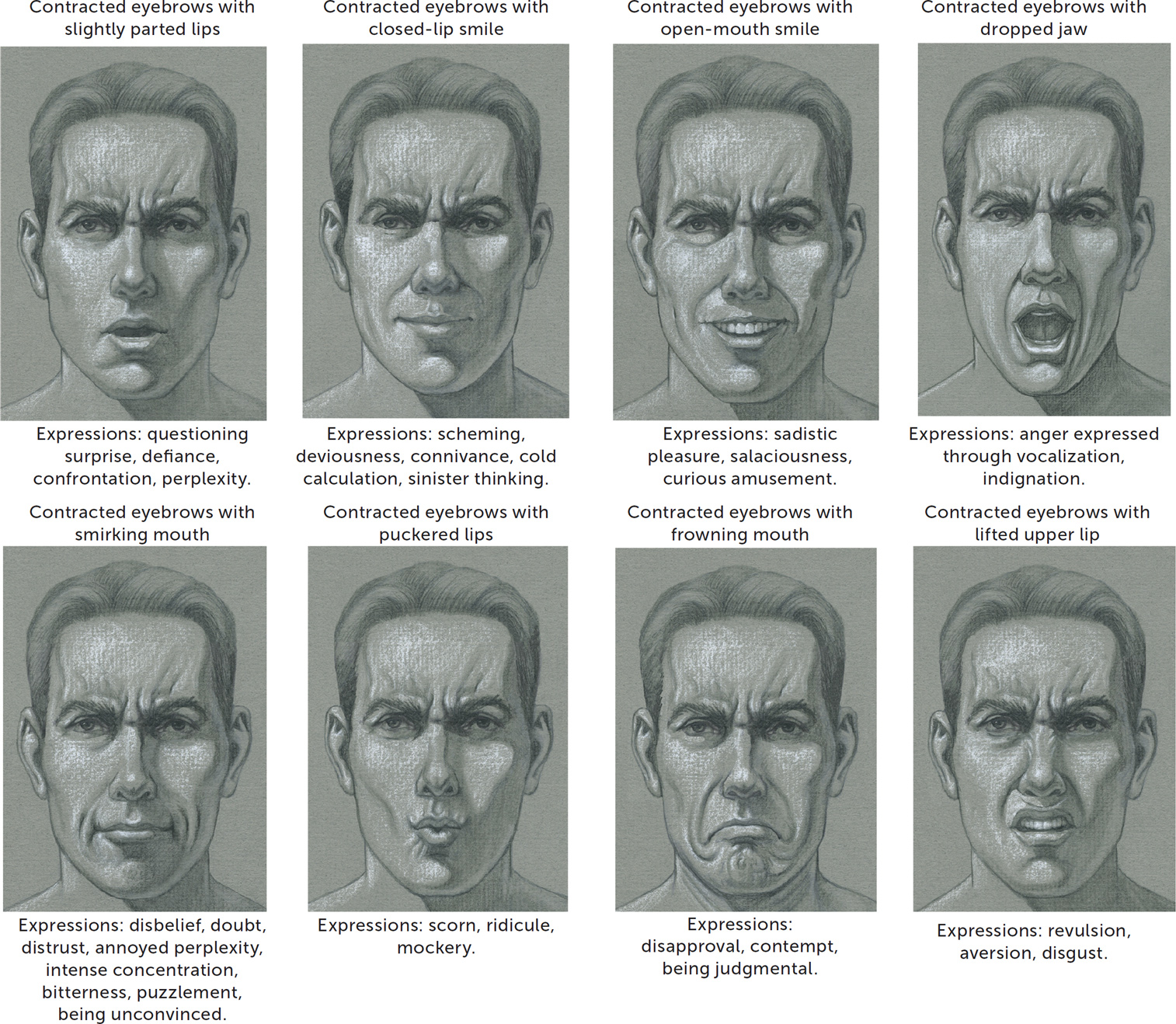

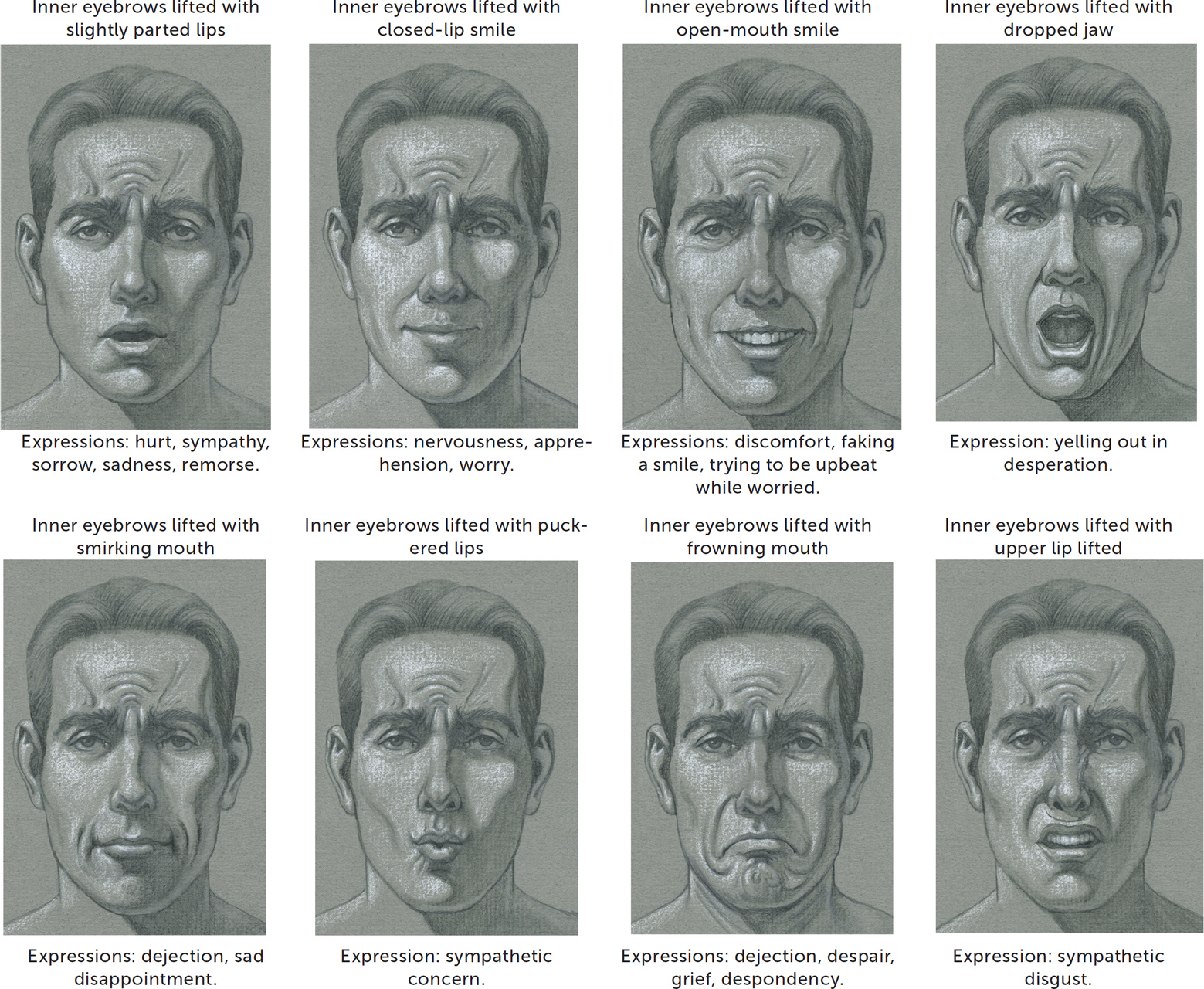

There are many ways to study expressions of the face. Young artists often begin by copying the expressions of their favorite comic book or manga characters. Usually, artists start out by learning basic expressions such as happiness, anger, sadness, fear, surprise, and disgust and from there continue to investigate variations on these basic emotions. One way to carry on that investigation is to study how each individual muscle produces a certain action when it contracts and how that action influences the skin by producing wrinkles such as laugh lines, worry lines, frown lines, or crow’s feet. For example, when the frontalis muscle of the forehead lifts the eyebrows, the action produces a set of curving horizontal wrinkles on the forehead. All by itself—that is, even when the rest of the face is neutral—this action can express several emotions, including disbelief and mild surprise. When the action of lifting the eyebrows is combined with movements of the mouth, various other expressions result.

Beyond understanding how each muscle moves when it contracts, it is good to develop an awareness of the many possible degrees of contraction, ranging from minimal, to moderate, to full or even exaggerated contraction. You can see the effects of differing degrees of contraction in the many variations of the smile, from the subtle “Mona Lisa smile” (is she smiling or not?), to a closed-lipped smile, to a smile with a slight parting of the lips, to a large, open grin. Moreover, these differing smiles indicate different emotions when combined with the actions of other facial muscles, such as the lifting or depression of the eyebrows.

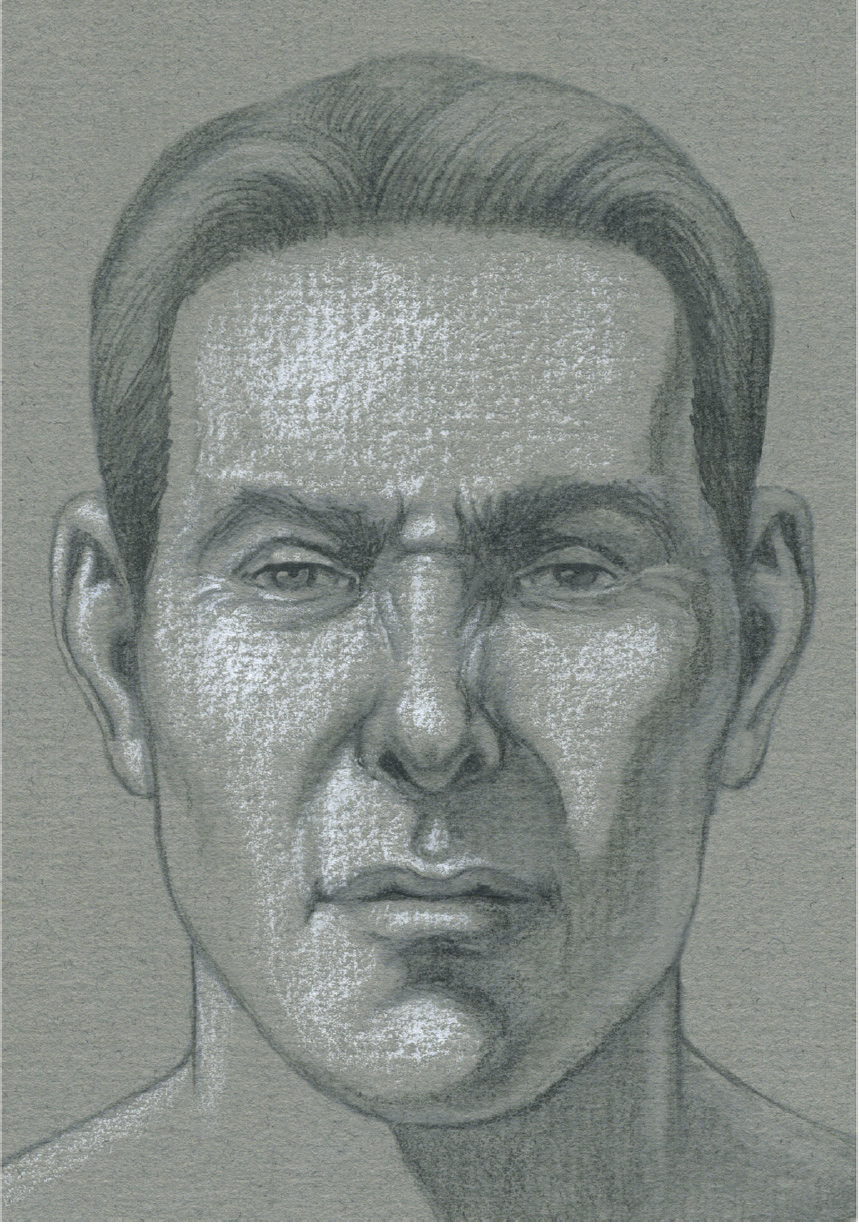

The groups of drawings on the following pages depict “mix and match” combinations of various contracting facial muscles. Do note that the activation of multiple facial muscles in multiple combinations and in varying degrees of contraction can produce countless facial expressions—many more than can possibly be explored here. Also be aware that a given expression might indicate more than one emotion.

LIFTED EYEBROWS, WITH MUSCLES CONTRACTING IN THE LOWER FACE

CONTRACTED EYEBROWS, WITH MUSCLES CONTRACTING IN THE LOWER FACE

LIFTED INNER EYEBROWS, WITH MUSCLES CONTRACTING IN THE LOWER FACE

Muscles That Move the Jaw

We now move from the facial muscles per se to the muscles that move the jaw (mandible). These muscles are like the skeletal muscles of the rest of the body in that they begin and insert on bones, and move bones rather than soft tissues.

The mandible, which is the only movable bone of the head, is hinged to the cranium at the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) by a series of ligaments. The movements of closing and opening the mandible are produced by two different muscle groups: One group, called the muscles of the mandible, attaches from the cranium into the mandible and helps close the dropped jaw. The other group, called the suprahyoid muscle group, attaches from the bottom portion of the mandible into the hyoid bone of the neck and helps drop the jaw.

The actions of closing and opening the jaw participate in vocalizations of differing qualities and intensities, such as humming, singing, yelling, calling out, screaming, talking, and laughing. Of course, the action of dropping the jaw without vocalizing can help create certain facial expressions, such as those indicating surprise, astonishment, and disbelief. And, as mentioned earlier, the movement of the jaw is essential for eating.

Muscles of the Mandible

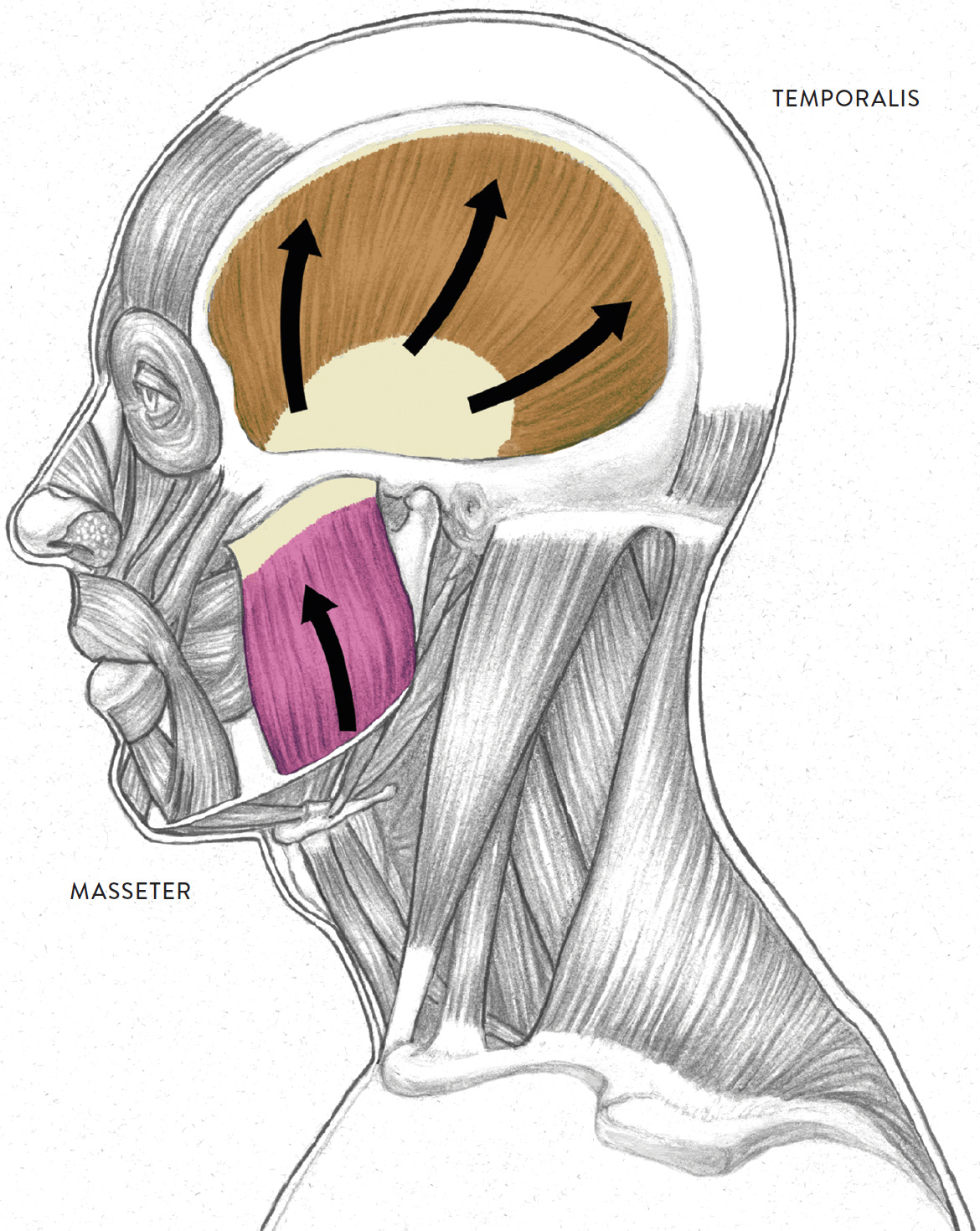

The muscles of the mandible are located in the lateral (side) region of the cranium and mandible. There are two muscles in this group: the temporalis and the masseter. When they contract, they elevate (lift) the mandible, which is the action of closing an opened or dropped jaw.

MUSCLES OF THE MANDIBLE

Arrows indicate direction of muscular contraction.

The temporalis (pron., TEM-poor-AL-liss or TEM-poh-RA-liss) is a large fan-shaped muscle positioned on the side of the cranium. This muscle attaches on the outer side of the cranium in a region called the temporal fossa (hence the name temporalis). It converges into a small tendon that attaches into the upper part of the mandible. Often, the muscle is hard to detect on the surface because it is hidden by hair. If, however, the hair is very closely cropped or the head is bald, then a small portion of the muscle near the temples can be seen when it is contracting (as in the act of chewing), creating a rippling effect on the skin.

The masseter (pron., MASS-ee-tur or maa-SEE-tur) is a bulky, rectangularly shaped muscle located on the outer cheek region. It begins on the lower zygomatic bone and zygomatic arch (cheekbone) and inserts into the outer surface of the mandible. The parotid gland (an ear-shaped glandular form) covers a portion of the masseter muscle. Not only does the masseter participate in the action of closing an opened jaw, but it also helps protract the mandible, moving the jaw slightly forward in the action of jutting the chin, which occurs in expressions of stubbornness or defiance. When the jaw is closed but the masseter is contracting without moving the jaw (isometric contraction), a rippling effect can be seen in the skin of the outer check. This occurs when a person is grinding his or her teeth and is seen in expressions of annoyance, nervousness, and emotional tension.

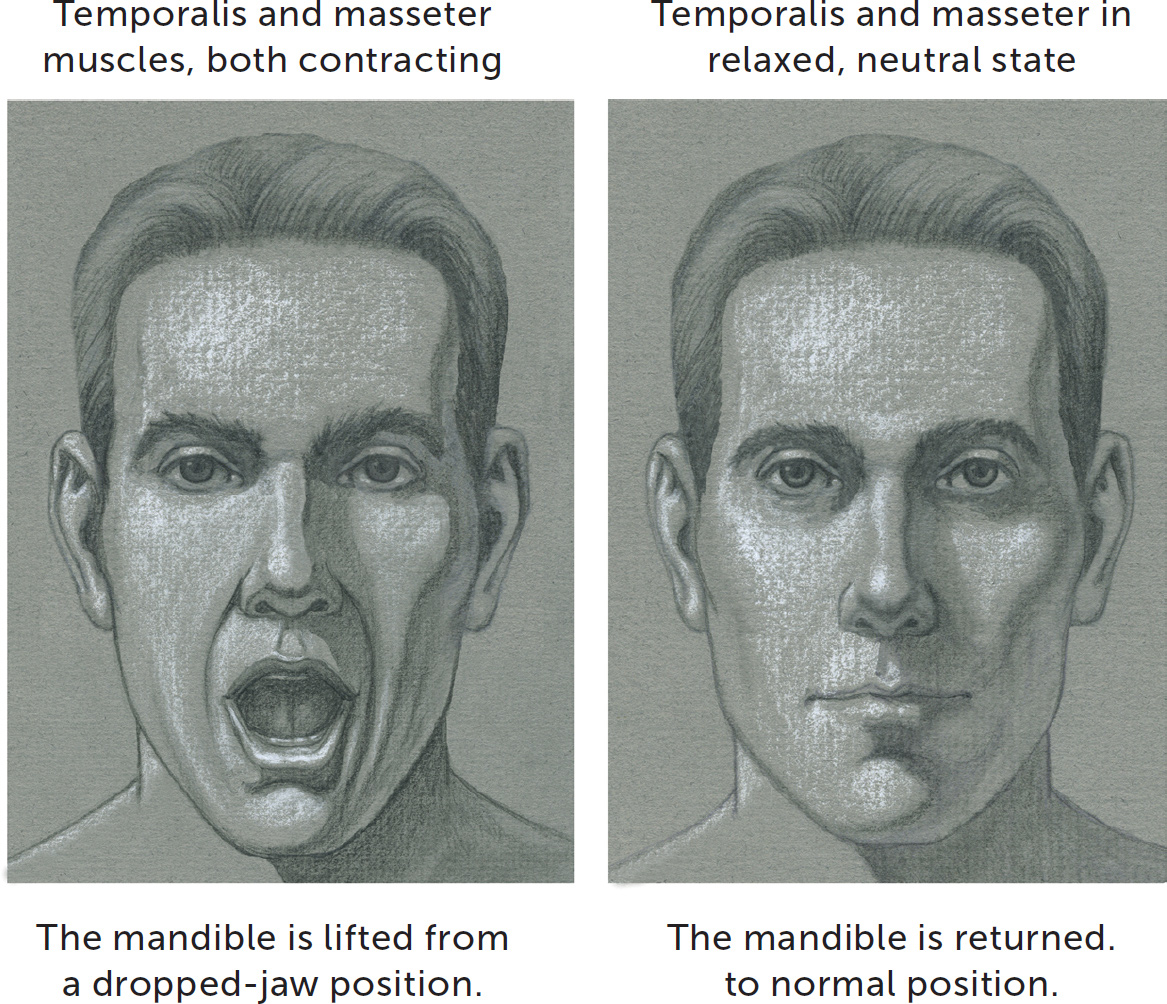

The temporal and masseter muscles and their actions are shown in the following drawings.

MUSCLES OF THE MANDIBLE—TWO STUDIES

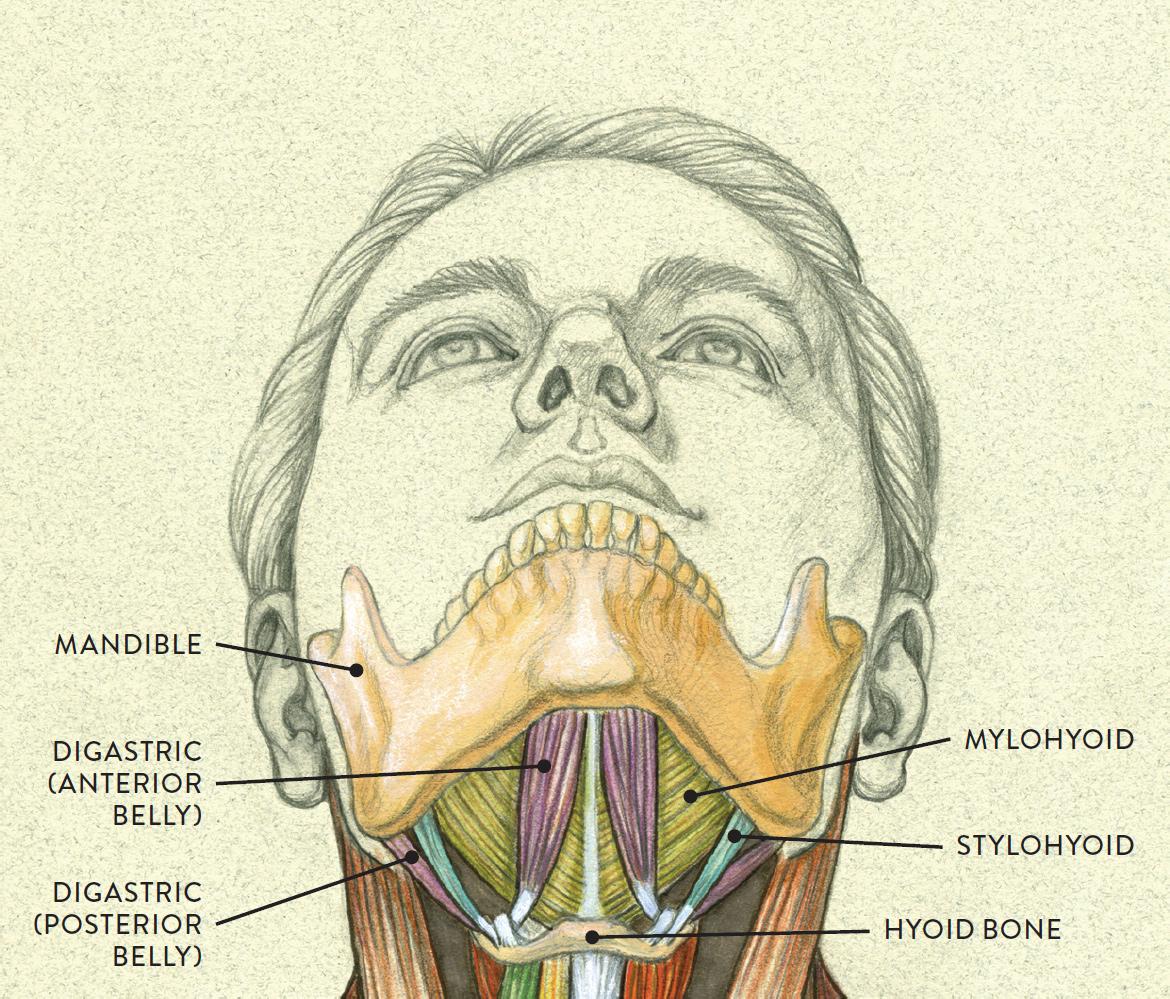

The Suprahyoid Muscle Group

Occupying a space immediately below the jaw is a triangularly shaped region commonly called the bottom plane of the jaw. Its boundaries are the edges of the mandible up to the cylinder of the neck and the hyoid bone, a small horseshoe-shaped structure that is rarely seen on the surface except in the extreme extension (hyperextension) of the neck and head. Many small muscles attach to it, helping move it upward and downward (along with the larynx) during the action of swallowing.

The three main muscles of the bottom plane of the jaw are collectively known as the suprahyoid muscles; the term suprahyoid means “above the hyoid.” These muscles are the digastric (anterior and posterior bellies), the mylohyoid, and the stylohyoid. Their main function is to depress (lower or open) the jaw and elevate (lift) the hyoid bone.

The bottom plane of the jaw is an important shape for artists to indicate (if it can be seen in a given pose) because it is a transition to the cylindrical form of the neck. Some beginning figurative artists have a tendency to neglect the bottom plane of the jaw when it is visible in a pose, giving this transitional area an unnatural flatness. Indicating shadows and reflected light in this region helps create the transition. The bottom plane of the jaw is mostly seen in three-quarter and side views and usually cannot be seen directly from the front unless the head is tilting back.

SUPRAHYOID MUSCLE GROUP

Anterior view of head tilting back

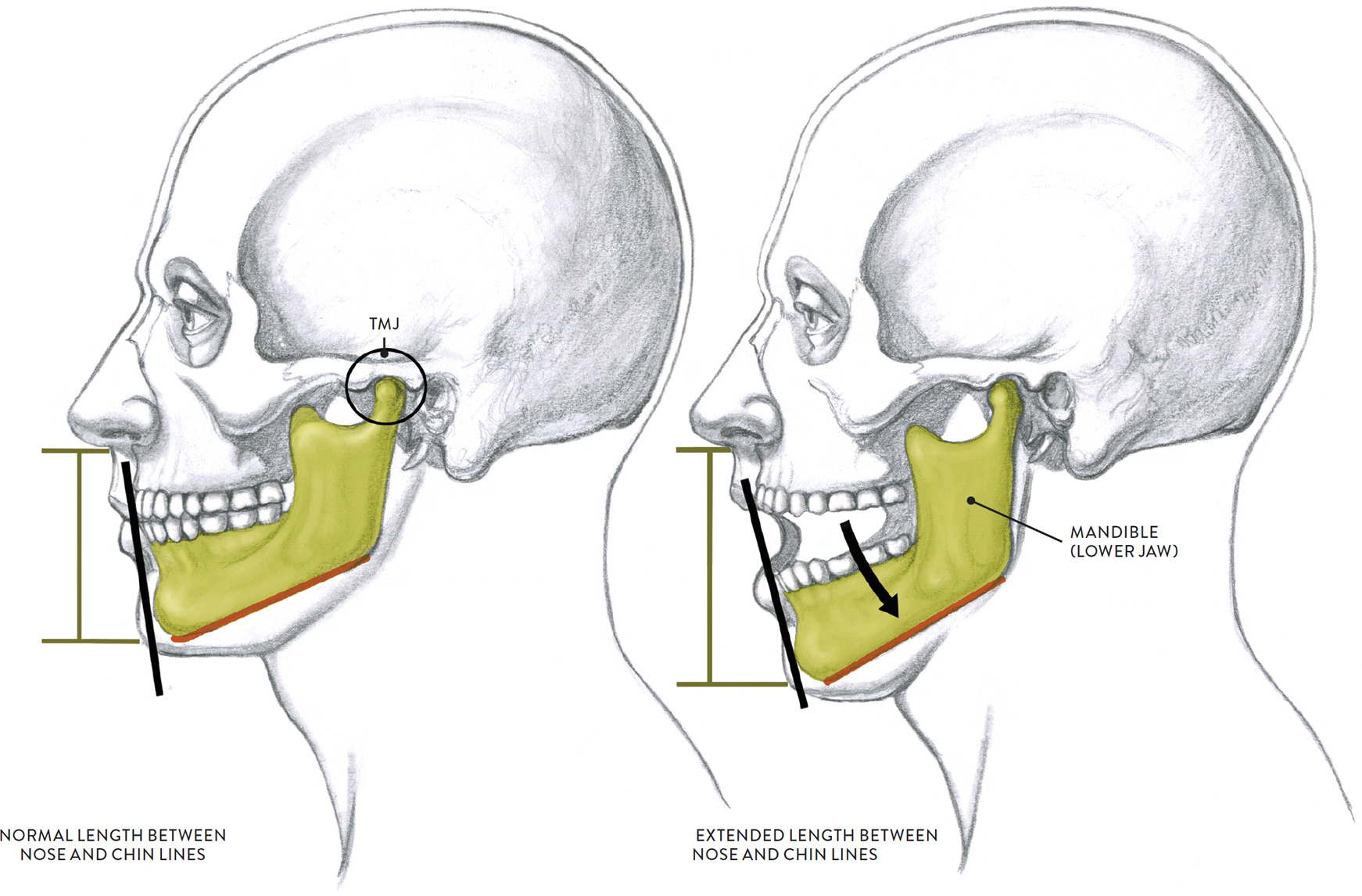

Open-Mouth Expressions

As previously discussed, the mandible (lower jawbone) is the only movable bone of the cranium, and its movement takes place at the temporomandibular joint, or TMJ. Movements of the lower jaw include forward and backward movements (protraction and retraction) as well as side-to-side movements (adduction and abduction), but the jaw’s main action is to lower, opening the mouth, and then close back up again (depression and elevation). Some artists find this action challenging to depict, so here are a few tips to follow when drawing an open-mouth expression (also summarized visually in this drawing):

1. Respect the limitations of jaw movement. Some artists tend to drop the jaw farther down than it can actually go, giving the face a strange, distorted look. Because of the bony restrictions of the TMJ and the ligaments that bind the joint, the mandible can only open to a certain degree—at maximum about two inches, or three finger-widths between the upper and lower front teeth. The soft forms of the lips, however, can stretch beyond the limitation of the TMJ, which is why the mouth can appear to open wider.

2. Add some length to the face. An opposite issue is that some artists do not add enough extra length to the front of the face when depicting an open-mouth expression. Proportionally speaking, the distance from the top of the head to the chin is greater when the jaw is dropped than when the mouth is closed, so make sure you place the bottom of the chin slightly lower than it would be normally. But be careful not to overdo it; adding too much length will make the jaw look dislocated.

3. Keep in mind that the chin swings slightly back when the jaw is lowered. Looking at a mouth opening from a side view, you see that the jaw does not drop straight down vertically but rather at a slight angle. Be sure to check the alignment between the front portions of the lips, teeth, and chin, as indicated by the black line in the drawing below. Also check the angle of the bottom border of the lower jaw. Since the chin drops down and swings back, this border is more tilted when the jaw is open. (It will be harder to detect the lower border of the jaw if the person you’re portraying has substantial subcutaneous tissue in this region.)

OPEN-MOUTH EXPRESSIONS—KEY CONSIDERATIONS

The heavy black lines show the change in alignment between the upper and lower jaws when the mandible (lower jaw) drops. The orange lines show the increasing tilt of the lower border of the jaw. The arrow in the drawing at right shows the direction of the dropping of the jaw (depression of the mandible).

The Teeth and Dental Arches in Open-Mouth Expressions

In a smile with parted lips and a closed jaw, you generally will see six front teeth on the upper dental arch—the four incisors and two cuspids. If the lips are positioned farther apart with the jaw dropping downward, you may see a few of the front teeth on the lower dental arch, as well. As can be seen in the life studies below, in very exaggerated open-mouth poses, you might see a portion of the horseshoe shape of the upper or lower dental arch, depending on the way the head is positioned and the vantage point from which you view the head.

Drawing the dental arches within an open mouth can be quite challenging. When the mouth opens, the upper and dental arches are pulled apart, with the upper arch remaining stationary while the lower arch drops. If you are sitting at eye level with a model whose jaw is dropping in an exaggerated way, you will be able to see a certain portion of the horseshoe shape of the lower dental arch. If you are viewing that model from a lower vantage point, or if the model’s head is dramatically tilted back, you will most likely see some of the upper dental arch.

If the front teeth are clearly seen in an open-mouth expression, make sure to line the teeth up correctly: The two large incisors (front teeth) of the upper dental arch should be placed on either side of the midline of the face with the other incisors positioned next to them. Any other teeth you see should appear to slightly recede because of their positions on the horseshoe-shaped dental arch. (The same principles apply to the lower dental arch.) Avoid outlining each tooth heavily, instead depicting the front portion of the dental arch as a simple shape, with very lightly drawn lines separating the teeth.

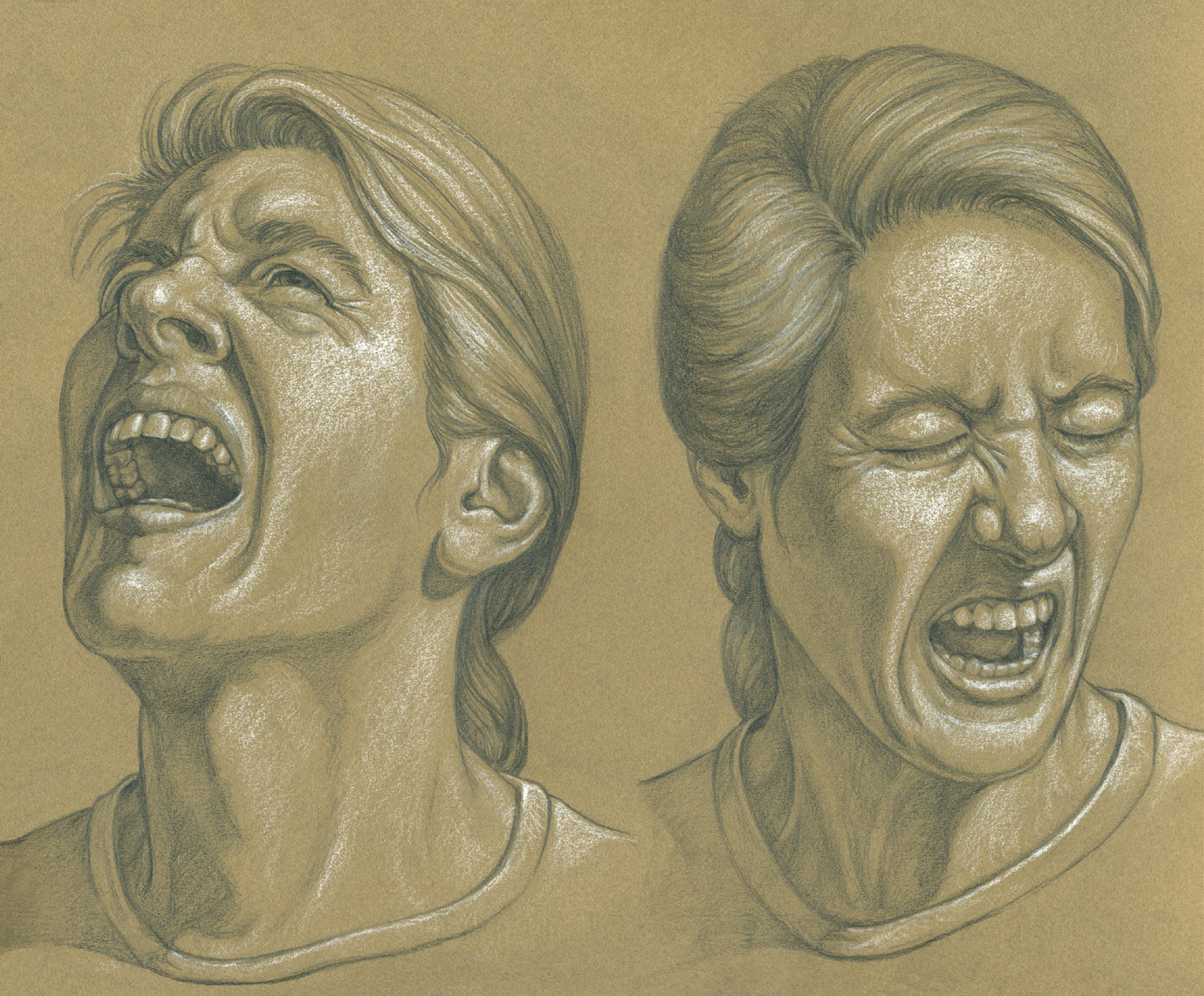

LIFE STUDIES SHOWING DENTAL ARCHES IN OPEN-MOUTH EXPRESSIONS

Graphite pencil and white chalk on toned paper.

The Lips in Open-Mouth Expressions

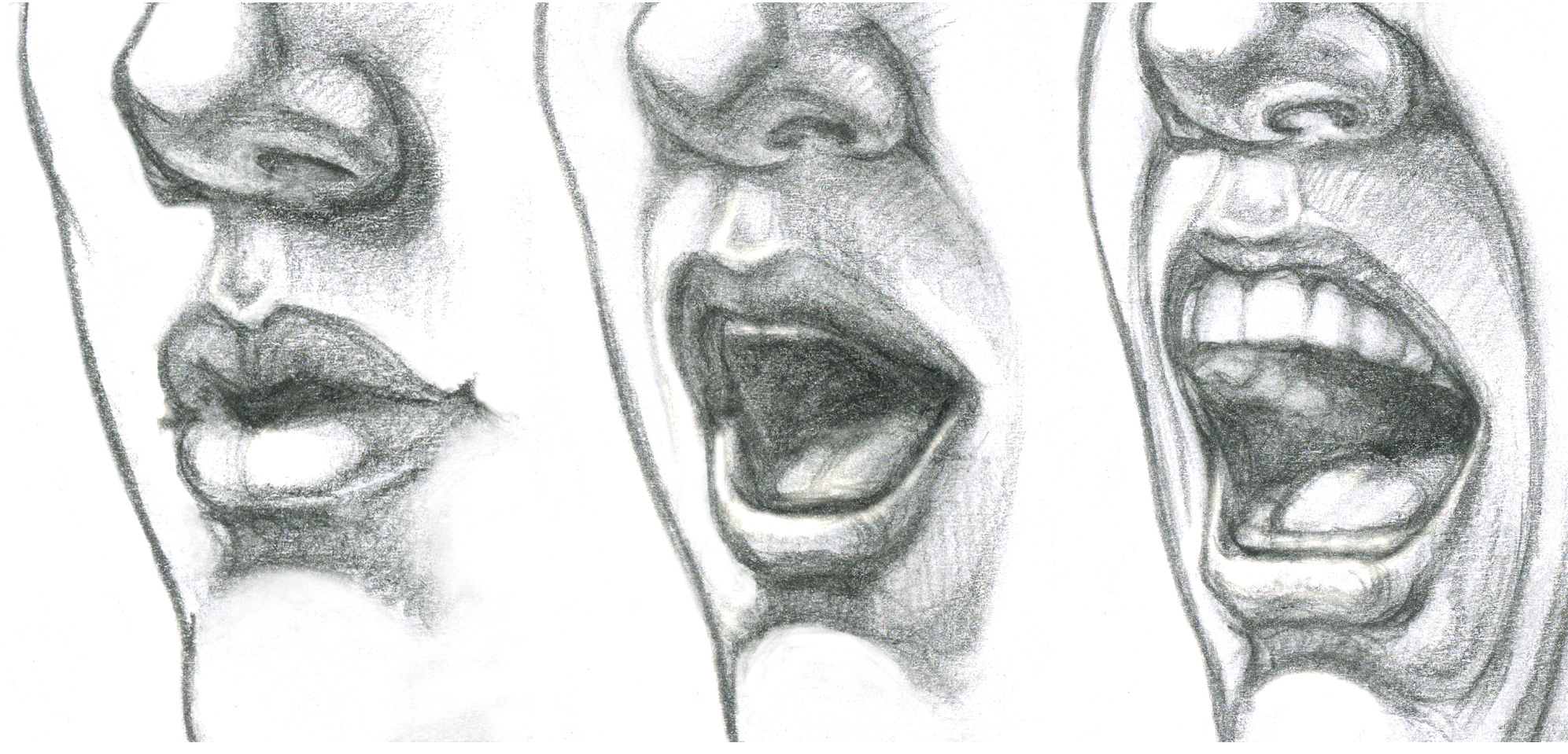

When the jaw drops, the lips are stretched in different ways, depending on which muscles are activated to create a certain expression or configuration of the mouth. The lips can be stretched vertically or horizontally or can protrude outward. If the jaw is dropped in an exaggerated way, the upper lip will wrap snuggly around the curvature of the teeth. The next drawing shows how the lips change shape as the jaw drops and how this action produces creases on the skin.

SHAPE OF THE LIPS IN OPEN-MOUTH EXPRESSIONS

LEFT: Lips and lower jaw in neutral position

CENTER: Lower jaw dropping with lips pulling part

RIGHT: Lower jaw dropping to maximum position

The upper lip wraps tightly around the upper teeth, and the lower lips stretch as far as possible.

Other Aspects of Open-Mouth Expressions

Opening the mouth involves the action of two different kinds of “hinges”: One is the bony hinge of the TMJ; the other is the soft-tissue hinge of the corner of the mouth. Each corner of the mouth (also known as the commissure of the mouth) act as a hinge whenever the upper and lower lips pull apart from each other. These outer corners can stretch in slightly different directions (forward, upward, downward) depending on which muscles are contracted, but they never disappear completely, even in an exaggerated open-mouth expression in which the lips are stretched as far as possible.

The space between the lips is an important consideration when depicting various open-mouth expressions. The opening can appear as a vertical oval shape or a rectangular or square shape. Sometimes it is an elongated horizontal oval, with tapered corners at each end. And in three-quarter views, the opened space might have a contorted, kidney-bean shape. Getting the shape right is key to drawing a convincing opened mouth.

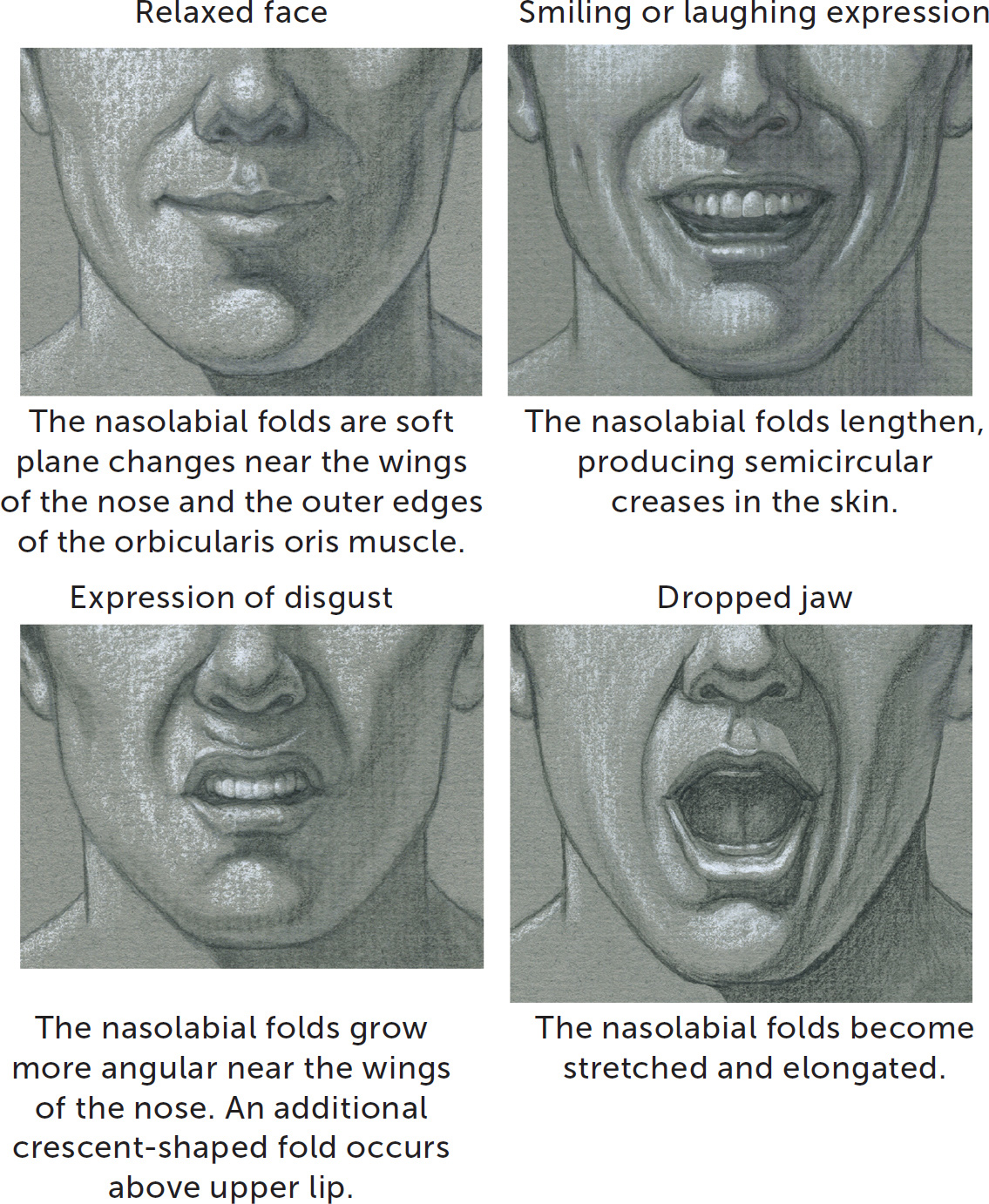

When the jaw drops, various skin creases appear in the lower face. Most notable are the nasolabial folds, which begin near the wings of the nose and swing in curves around the outer perimeters of the orbicularis oris muscle. Shown in the following drawing, the nasolabial folds are activated in smiling, in expressions of disgust, and also in wide-mouth expressions in which the jaw drops dramatically. Depending on the shape and action of the lips, the nasolabial folds can be angular or curved. Additional skin folds may also appear around the chin, curving upward into the lower face.

NASOLABIAL FOLDS

When the jaw drops, it stretches the muscles of the jaw and lower face as well as the skin and subcutaneous tissue, making the lower part of the face appear narrower when viewed from the front. The bottom plane of the jaw and the muscles and other soft tissues in this region can become compressed, appearing as a thick roll on a lean person or as multiple rolls on a heavy person.

To study how the lips change shape on an opened mouth, you may want to collect photo references, possibly including photos you take yourself of people—friends, family, hired models—making different expressions with their mouths open. While such photos might look staged, they can serve you well as basic guides. Observing the faces of singers, especially opera singers, can also be helpful. Professional singers learn to pronounce syllables in an exaggerated way so that the words they sing can be clearly heard by an audience. An interesting exercise is to freeze-frame a video of a singer and do quick sketches of the singer’s face, emphasizing the mouth region. The same exercise can be done with film or TV actors: freeze the video when they are engaging in emotional exchanges of dialogue, and do quick studies of the close-ups.

For real-life facial expressions that do not look staged, try drawing from photos of people reacting emotionally to various events, such as sports events, tragic news events, and so on. Such photos show raw, unrehearsed emotion.

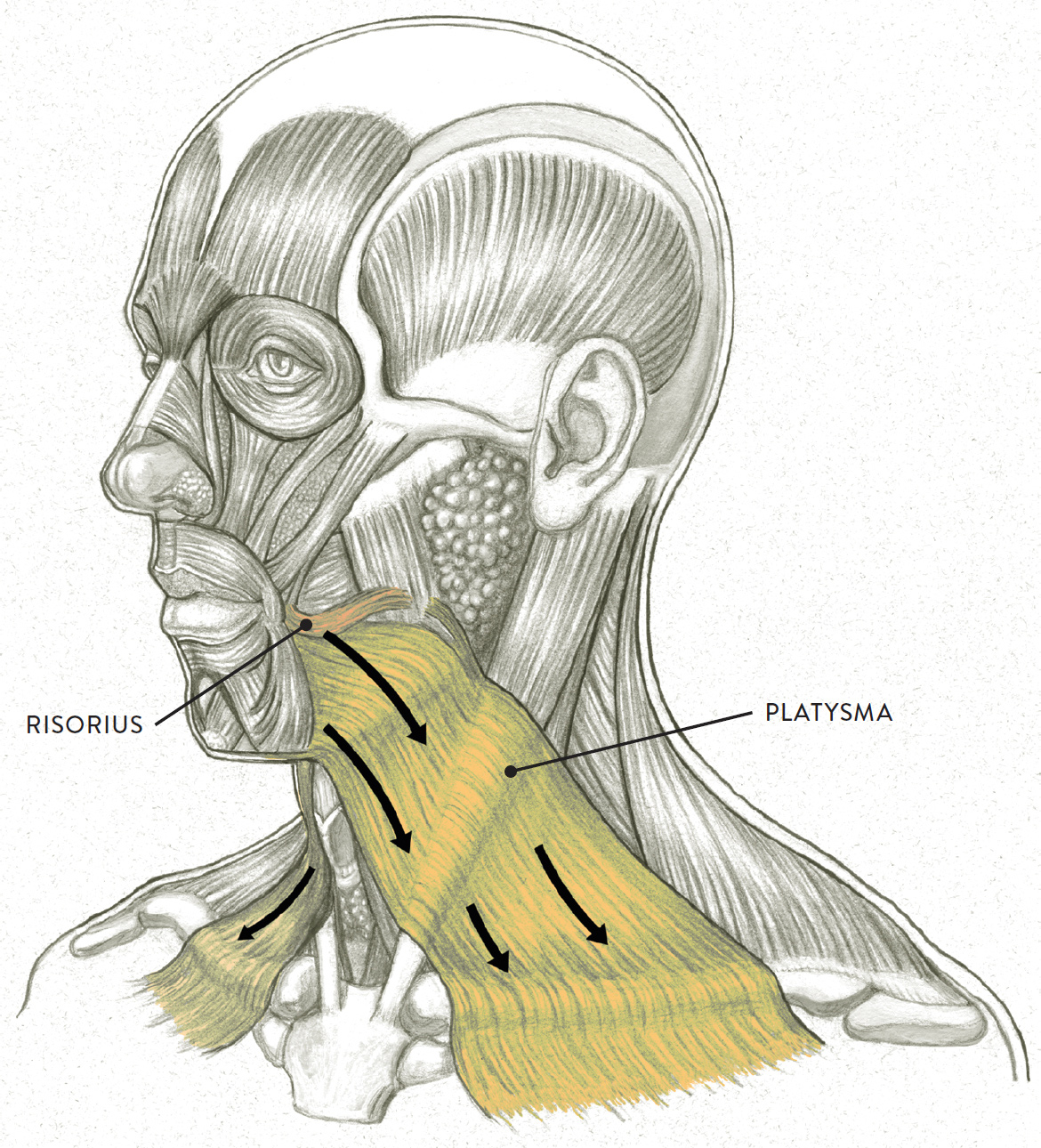

The Platysma and Risorius Muscles

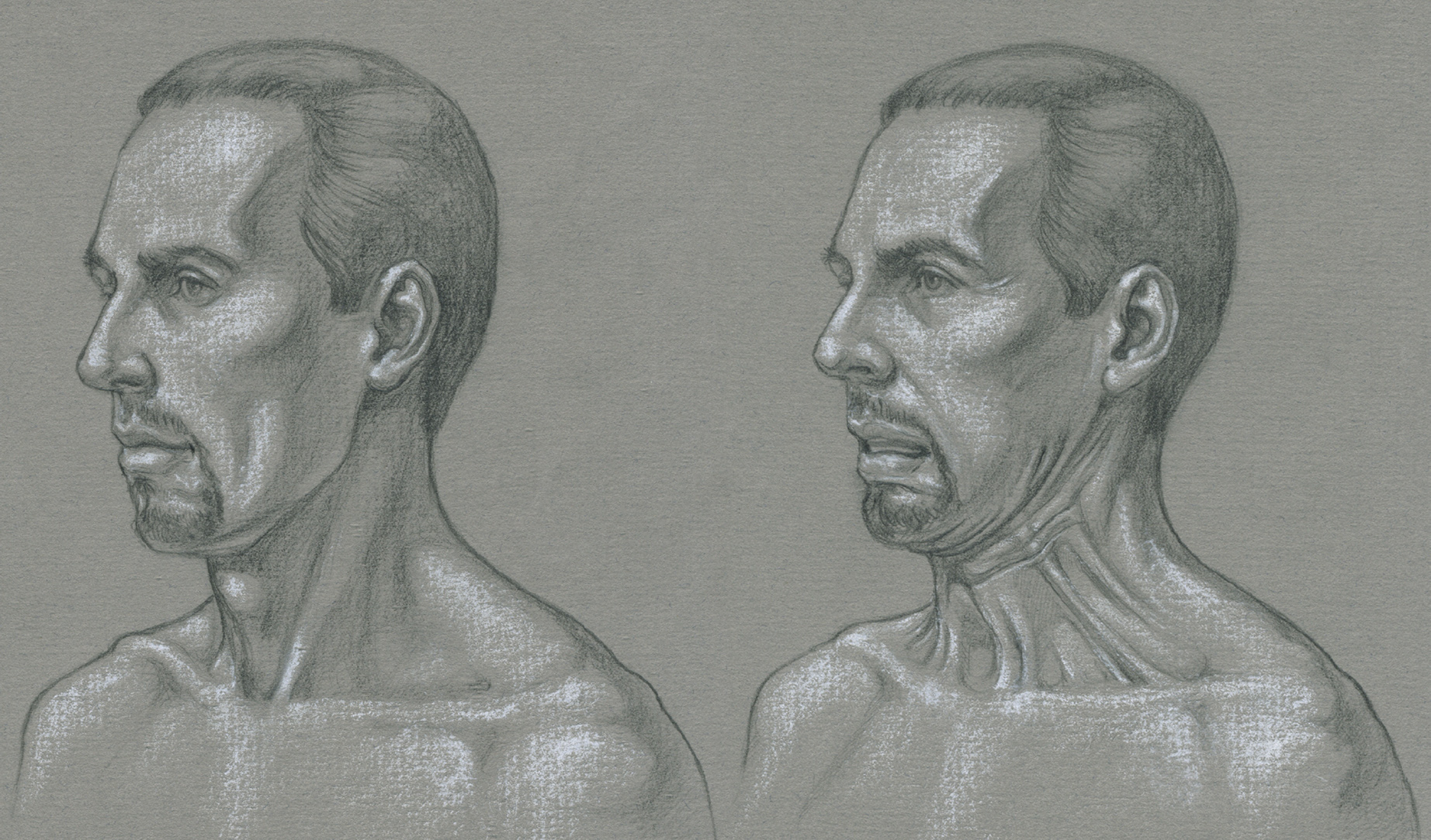

There is one muscle that, though it is mostly not located on the face, can have a significant effect on some facial expressions. This is the platysma (plah-TIZ-mah), a thin, sheetlike muscle embedded within the subcutaneous layer and fascia on the neck and upper chest region. As shown in the drawing below, the platysma begins in the fascia of the chest near and around the clavicles and inserts into the base of the mandible, each modiolus (angle of the mouth), and the skin of the lower lip and cheek region. When the platysma muscle contracts, it tenses the skin on the neck and lower face. Cordlike vertical skin ridges, called platysmal banding, appear on the front of the neck, as do some transverse skin creases. The platysma also pulls the corners of the mouth downward and lowers the mandible, producing a grimace, as can be seen in the right-hand study in the following drawing. The full contraction of the muscle is seen in expressions of terror, disgust, and extreme pain. This muscle, not seen on a youthful person unless contracted, does become more noticeable as people age. The vertical neck folds (platysmal banding) are caused by the loosening of the platysma muscle, which occurs when the fatty tissue dissipates and the skin, along with the muscle, loses its elasticity, giving the neck region a “creped” (wrinkled) appearance. These ridges are colloquially called “wattles” or “turkey neck.”

PLATYSMA—TWO STUDIES IN THREE-QUARTER VIEW

LEFT: Platysma muscle relaxed

RIGHT: Platysma muscle contracting

The risorius (pron., rih-SOR-ee-us) is a slender muscle, with only a few muscle fibers, positioned below the zygomaticus major. Near the modiolus (angle of mouth), the muscle’s fibers blend with some of the fibers of the platysma muscle (see this page). The risorius begins on the fascia over the platysma muscle and inserts into the skin at the modiolus. When the risorius muscles contract they stretch and tense the lips at their outer corners, especially when the mouth widens during laughter or in a strained expression such as a grimace.

PLATYSMA, WITH RISORIUS MUSCLE—THREE-QUARTER VIEW

Arrows indicate direction of muscular contraction.

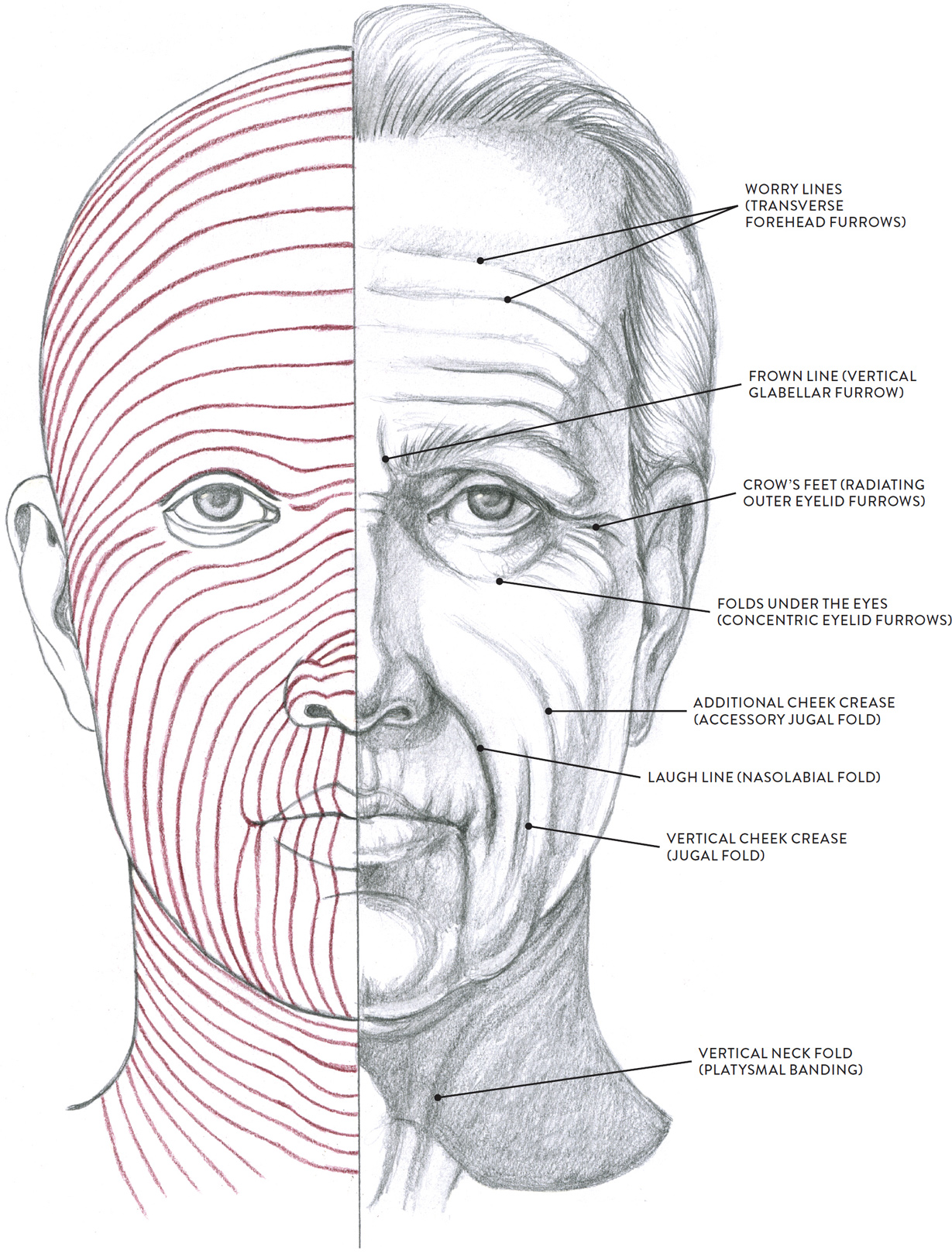

Facial Wrinkle Patterns

Artists who truly want to understand facial expressions should be aware of the patterns of wrinkles that occur in the skin of the face, growing more pronounced and permanent as a person ages. Throughout the body, series of natural linear pathways composed of collagen fibers are embedded within the aponeurotic sheets of deep fascia. These are called Langer’s lines, after the Austrian anatomist Karl Langer (1819–1887), who was one of the first to map them. Surgeons use these lines as guides for incisions to ensure better healing. Most Langer’s lines are not visible on the surface form, but some correspond closely to the skin creases in the face (called expressive lines or dynamic lines) that are activated by contracting facial muscles during expressions. The following list gives their common names, their anatomical names, and the facial expressions with which they are associated:

· Worry lines are transverse (horizontal) forehead furrows that occur in expressions of surprise and worry.

· Crow’s feet are radiating outer eyelid furrows that occur in expressions of amusement and laughter.

· Frown lines (vertical glabellar furrows) occur in expressions of anger and annoyance.

· Laugh lines (nasolabial folds) occur in smiles and laughter.

· Vertical cheek creases (jugal folds, accessory jugal folds) occur in smiling, laughing, and smirking.

· Folds under the eyes (concentric eyelid furrows) occur in smiling and laughter when the cheeks are pushed up into the lower eye-socket region.

· Vertical neck folds (platysmal banding) occur in grimacing and expressions of terror.

LANGER’S LINES AND FACIAL WRINKLE PATTERNS

LEFT: Langer’s lines

RIGHT: Pattern of facial wrinkles

Over time, as the elasticity of the skin is weakened by aging, these skin creases (wrinkles) become permanently “etched” in the facial skin, making the pathways of the Langer’s lines more visible. The drawing opposite clearly shows how facial wrinkles follow pathways that are almost identical to those of the Langer’s lines. Awareness of the general pattern of Langer’s lines can help artists place various facial wrinkles more accurately—knowledge that can be applied when depicting facial expressions generally or in studies of elderly faces.

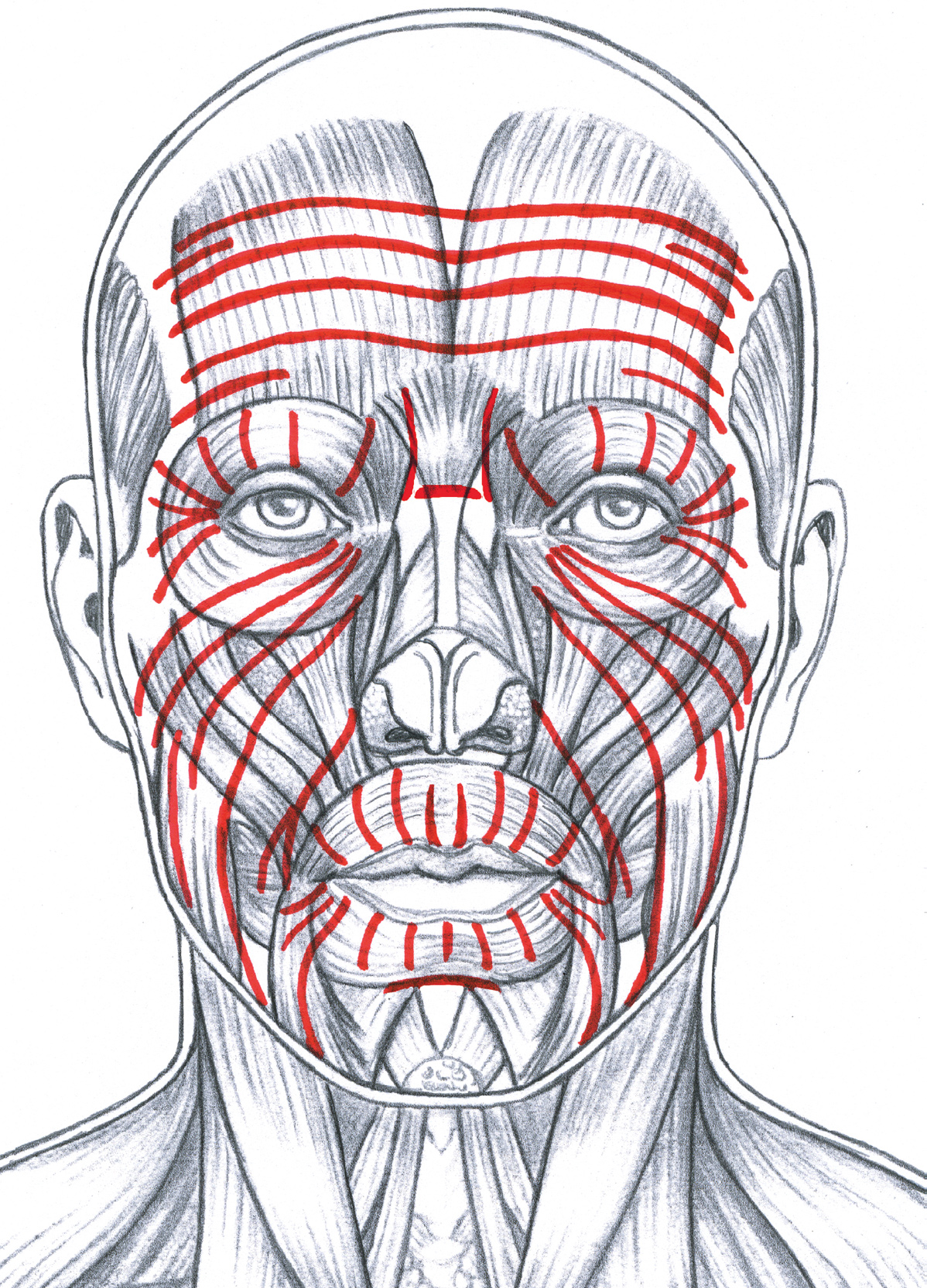

Wrinkles occurring in a facial expression are usually perpendicular to the underlying contracting muscle fibers. For example, the frontalis muscle of the forehead contracts in a vertical direction (lifting the eyebrows upward), yet the wrinkles created on the surface of the skin are horizontal, like the Langer’s lines in this region. The next drawing shows the basic wrinkle pattern of the skin superimposed on the underlying muscles.

WRINKLE PATTERN OF FACE, PERPENDICULAR TO UNDERLYING MUSCLES

The red lines indicate the general pattern of facial wrinkles, corresponding to the dynamic lines of facial expressions. The wrinkles generally run perpendicular to the underlying muscle fibers.

MALE FIGURE IN THREE-QUARTER VIEW

Graphite pencil and white chalk on toned paper.