THE LIVING WORLD

Unit Four. The Evolution and Diversity of Life

15. How We Name Living Things

15.4. What Is a Species?

The basic biological unit in the Lin- naean system of classification is the species. John Ray (1627-1705), an English clergyman and scientist, was one of the first to propose a general definition of species. In about 1700, he suggested a simple way to recognize a species: All the individuals that belong to it can breed with one another and produce fertile offspring. By Ray’s definition, the offspring of a single mating were all considered to belong to the same species, even if they contained different-looking individuals, as long as these individuals could interbreed.

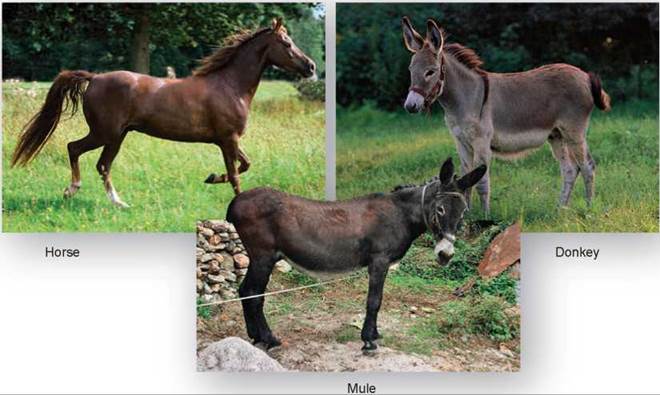

All domestic cats are one species (they can all interbreed), while carp are not the same species as goldfish (they cannot interbreed). The donkey you see in figure 15.4 is not the same species as the horse, because when they interbreed, the offspring—mules—are sterile.

Figure 15.4. Ray's definition of a species.

According to Ray, donkeys and horses are not the same species. Even though they produce very hardy offspring (mules) when they mate, the mules are sterile, meaning that they cannot produce offspring.

The Biological Species Concept

With Ray’s observation, the species began to be regarded as an important biological unit that could be cataloged and understood, the task that Linnaeus set himself a generation later. Where information was available, Linnaeus used Ray’s species concept, and it is still widely used today. When the evolutionary ideas of Darwin were joined to the genetic ideas of Mendel in the 1920s to form the field of population genetics, it became desirable to define the category species more precisely. The definition that emerged, the so-called biological species concept, discussed in chapter 14, defined species as groups that are reproductively isolated. In other words, hybrids (offspring of different species that mate) occur rarely in nature, whereas individuals that belong to the same species are able to interbreed freely.

As we learned in chapter 14, the biological species concept works fairly well for animals, where strong barriers to hybridization between species exist, but very poorly for members of the other kingdoms. The problem is that the biological species concept assumes that organisms regularly outcross— that is, interbreed with individuals other than themselves, individuals with a different genetic makeup from their own but within their same species. Animals regularly outcross, and so the concept works well for animals. However, outcrossing is less common in the other five kingdoms. In prokaryotes and many protists, fungi, and some plants, asexual reproduction, reproduction without sex, predominates. These species clearly cannot be characterized in the same way as outcrossing animals and plants—they do not interbreed with one another, much less with the individuals of other species.

Complicating matters further, the reproductive barriers that are the key element in the biological species concept, although common among animal species, are not typical of other kinds of organisms. In fact, there are essentially no barriers to hybridization between the species in many groups of trees, such as oaks, and other plants, such as orchids. Even among animals, fish species are able to form fertile hybrids with one another, though they may not do so in nature.

In practice, biologists today recognize species in different groups in much the way they always did, as groups that differ from one another in their visible features. Within animals, the biological species concept is still widely employed, while among plants and other kingdoms it is not. Molecular data are causing a reevaluation of traditional classification systems, and, taking into account morphology, life cycles, metabolism, and other characteristics, they are changing the way scientists classify plants, protists, fungi, prokaryotes, and even animals.

How Many Kinds of Species Are There?

Since the time of Linnaeus, about 1.5 million species have been named. But the actual number of species in the world is undoubtedly much greater, judging from the very large numbers that are still being discovered. Some scientists estimate that at least 10 million species exist on earth, and at least two- thirds of these occur in the tropics.

Key Learning Outcome 15.4. Among animals, species are generally defined as reproductively isolated groups; among the other kingdoms such a definition is less useful, as their species typically have weaker barriers to hybridization.