THE LIVING WORLD

Unit Eight. The Living Environment

35. Populations and Communities

35.8. Communities

Almost any place on earth is occupied by species, sometimes by many of them, as in the rain forests of the Amazon, and sometimes by only a few, as in the near-boiling waters of Yellowstone’s geysers (where a number of microbial species live). The term community refers to the species that occur at any particular locality, like the array of plants and animals that you see in the savanna photo in figure 35.16a as well as the ones you can’t see (like fungi, protists, and microbes). Communities can be characterized either by their constituent species, a list of all species present in the community, or by their properties, such as species richness (the number of different species present) or primary productivity.

Interactions among community members govern many ecological and evolutionary processes. These interactions, such as predation (figure 35.16b), competition (figure 35.16c), and mutualism, affect the population biology of particular species—whether a population increases or decreases in abundance for example—as well as the ways in which energy and nutrients cycle through the ecosystem. As explored in more detail in the next chapter, an ecosystem includes a community of living organisms and the nonliving components that surround them.

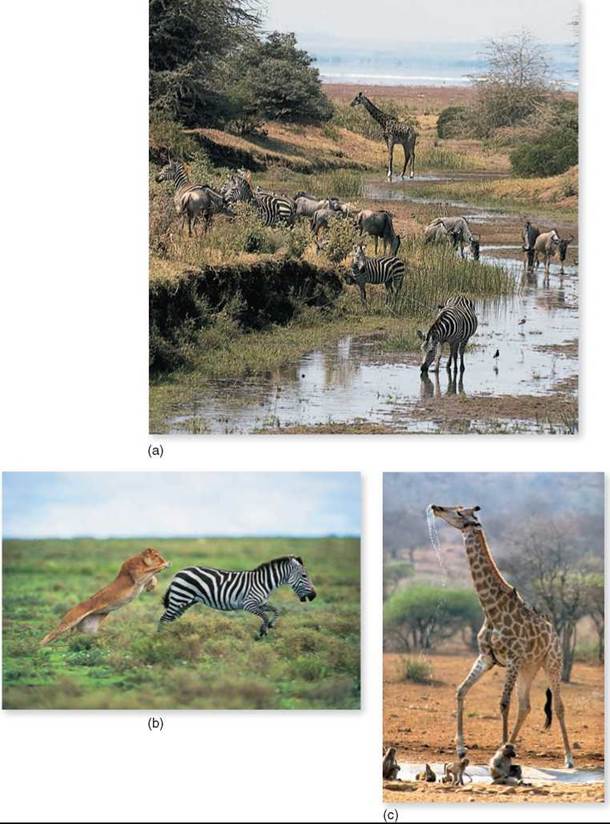

Figure 35.16. A Tanzanian savanna community.

A community consists of all the species—plants, animals, fungi, protists, and prokaryotes—that occur at a locality. (a) A savanna community in Lake Manyara National Park in Tanzania. Species within a community interact with each other, such as through predation in (b) or competition for a resource in (c).

Scientists study biological communities in many ways, ranging from detailed observations to elaborate, large-scale experiments. In some cases, such studies focus on the entire community, whereas in other cases only a subset of species that are likely to interact with each other are studied. Regardless of how they are studied, two views exist on the makeup and functioning of communities.

The individualistic concept of communities, first championed by H. A. Gleason of the University of Chicago early in the twentieth century, holds that a community is nothing more than an aggregation of species that happen to co-occur at one place. By contrast, the holistic concept of communities, which can be traced to the work of F. E. Clements, also about a century ago, views communities as an integrated unit. In this sense, the community could be viewed as a superorganism whose constituent species have coevolved to the extent that they function as a part of a greater whole, just as the kidneys, heart, and lungs all function together within an animal’s body. In this view, then, a community would amount to more than the sum of its parts.

Most ecologists today favor the individualistic concept. For the most part, species seem to respond independently to changing environmental conditions. As a result, community composition changes gradually across landscapes as some species appear and become more abundant, while others decrease in abundance and eventually disappear. Competition is an important factor that affects individuals and in so doing affects the community.

Key Learning Outcome 35.8. A community consists of all species that occur at a site. Their interactions shape ecological and evolutionary patterns.