5 Steps to a 5 AP Chemistry (2015)

STEP 3. Develop Strategies for Success

CHAPTER 4. How to Approach Each Question Type

IN THIS CHAPTER

Summary: Use these question-answering strategies to raise your AP score.

Key Ideas

Multiple-Choice Questions

![]() Read the question carefully.

Read the question carefully.

![]() Try to answer the question yourself before reading the answer choices.

Try to answer the question yourself before reading the answer choices.

![]() Drawing a picture can help.

Drawing a picture can help.

![]() Don’t spend too much time on any one question.

Don’t spend too much time on any one question.

![]() In-depth calculations are not necessary; approximate the answer by rounding.

In-depth calculations are not necessary; approximate the answer by rounding.

Free-Response Questions

![]() Write clearly and legibly.

Write clearly and legibly.

![]() Be consistent from one part of your answer to another.

Be consistent from one part of your answer to another.

![]() Draw a graph if one is required.

Draw a graph if one is required.

![]() If the question can be answered with one word or number, don’t write more.

If the question can be answered with one word or number, don’t write more.

![]() If a question asks “how,” tell “why” as well.

If a question asks “how,” tell “why” as well.

Multiple-Choice Questions

Because you are a seasoned student accustomed to the educational testing machine, you have surely participated in more standardized tests than you care to count. You probably know some students who always seem to ace the multiple-choice questions, and some students who would rather set themselves on fire than sit for another round of “bubble trouble.” We hope that, with a little background and a few tips, you might improve your scores on this important component of the AP Chemistry exam.

First, the background. Every multiple-choice question has three important parts:

1. The stem is the basis for the actual question. Sometimes this comes in the form of a fill-in-the-blank statement, rather than a question.

Example: The mass number of an atom is the sum of the atomic number and ________.

Example: What two factors lead to real gases deviating from the predictions of Kinetic Molecular Theory?

2. The correct answer option. Obviously, this is the one selection that best completes the statement or responds to the question in the stem. Because you have purchased this book, you will select this option many, many times.

3. Distracter options. Just as it sounds, these are the incorrect answers intended to distract anyone who decided not to purchase this book. You can locate this person in the exam room by searching for the individual who is repeatedly smacking his or her forehead on the desktop.

Students who do well on multiple-choice exams are so well prepared that they can easily find the correct answer, but other students do well because they are perceptive enough to identify and avoid the distracters. Much research has been done on how best to study for, and complete, multiple-choice questions. You can find some of this research by using your favorite Internet search engine, but here are a few tips that many chemistry students find useful.

1. Let’s be careful out there. You must carefully read the question. This sounds obvious, but you would be surprised how tricky those test developers can be. For example, rushing past, and failing to see, the use of a negative, can throw a student.

Example: Which of the following is not true of the halogens?

a. They are nonmetals.

b. They form monatomic anions with a –1 charge.

c. In their standard states they may exist as solids, liquids, or gases.

d. All may adopt positive oxidation states.

e. They are next to the noble gases on the periodic table.

A student who is going too fast, and ignores the negative not, might select option (a), because it is true and it was the first option that the student saw.

You should be very careful about the wording. It is easy to skip over small words like “not,” “least,” or “most.” You must make sure you are answering the correct question. Many students make this type of mistake—do not add your name to the list.

2. See the answer, be the answer. Many people find success when they carefully read the question and, before looking at the alternatives, visualize the correct answer. This allows the person to narrow the search for the correct option and identify the distracters. Of course, this visualization tip is most useful for students who have used this book to thoroughly review the chemistry content.

Example: When Robert Boyle investigated gases, he found the relationship between pressure and volume to be _________.

Before you even look at the options, you should know what the answer is. Find that option, and then quickly confirm to yourself that the others are indeed wrong.

3. Never say never. Words like “never” and “always” are absolute qualifiers. If these words are in one of the choices, it is rarely the correct choice.

Example: Which of the following is true about a real gas?

a. There are never any interactions between the particles.

b. The particles present always have negligible volumes.

If you can think of any situation where the statements in (a) and (b) are untrue, then you have discovered distracters and can eliminate these as valid choices.

4. Easy is as easy does. It’s exam day and you’re all geared up to set this very difficult test on its ear. Question number one looks like a no-brainer. Of course! The answer is 7, choice c. Rather than smiling at the satisfaction that you knew the answer, you doubt yourself. Could it be that easy? Sometimes they are just that easy.

5. Sometimes, a blind squirrel finds an acorn. Should you guess? Try to eliminate one or more answers before you guess. Then pick what you think is the best answer. You are not penalized for guessing, so don’t leave an answer blank.

6. Draw it, nail it. Many questions are easy to answer if you do a quick sketch in the margins of your test book. Hey, you paid for that test book; you might as well use it.

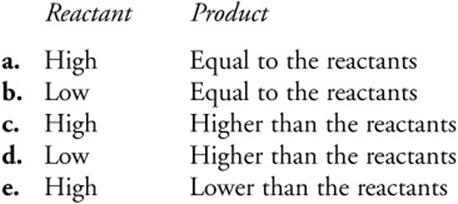

Example: The rate of the reverse reaction will be slower than the rate of the forward reaction if the relative energies of the reactants and products are:

These types of question are particularly difficult, because the answer requires two ingredients. The graph that you sketch in the margin will speak for itself.

7. Come back, Lassie, come back! Pace yourself. If you do not immediately know the answer to a question—skip it. You can come back to it later. You have approximately 90 seconds per question. You can get a good grade on the test even if you do not finish all the questions. If you spend too much time on a question you may get it correct; however, if you go on you might get several questions correct in the same amount of time. The more questions you read, the more likely you are to find the ones for which you know the answers. You can help yourself on this timing by practice.

Times are given for the various tests in this book; if you try to adhere strictly to these times, you will learn how to pace yourself automatically.

8. Timing is everything, kid. You have about 90 seconds for each of the 60 questions. Keep an eye on your watch as you pass the halfway point. If you are running out of time and you have a few questions left, skim them for the easy (and quick) ones so that the rest of your scarce time can be devoted to those that need a little extra reading or thought.

9. Think! But do not try to outthink the test. The multiple-choice questions are straight-forward—do not over-analyze them. If you find yourself doing this, pick the simplest answer. If you know the answer to a “difficult” question—give yourself credit for preparing well; do not think that it is too easy and that you missed something. There are easy questions and difficult questions on the exam.

10. Change is good? You should change answers only as a last resort. You can mark your test so you can come back to a questionable problem later. When you come back to a problem, make sure you have a definite reason for changing the answer.

Other things to keep in mind:

• Take the extra half of a second required to fill in the bubbles clearly.

• Don’t smudge anything with sloppy erasures. If your eraser is smudgy, ask the proctor for another.

• Absolutely, positively, check that you are bubbling the same line on the answer sheet as the question you are answering. I suggest that every time you turn the page you double-check that you are still lined up correctly.

Free-Response Questions

You will have 90 minutes to complete Section II, the free-response part of the AP Chemistry exam. There will be a total of seven free-response questions (FRQs) of two different types. Three questions will be of the multipart type. Plan on spending a maximum of 20–25 minutes per question on these three. You will be given some information (the question stem), and then you will have several questions to answer related to that stem. These questions will be, for the most part, unrelated to each other. You might have a lab question, an equilibrium constant question, and so on. But all of these questions will be related to the original stem. The other type of free-response question will be of the single-part type. There will be four of these. Plan on allowing 3–10 minutes per question.

There are a number of kinds of questions that are fair game in the free-response section (Section II). One category is quantitative. You might be asked to analyze a graph or a set of data, and answer questions associated with this data. In many cases you will be required to perform appropriate calculations.

Another category of questions will be ones that refer to a laboratory setting/experiment. These lab questions tend to fall into two types: analysis of observations/data or the design of experiments. In the first type you might be given a set of data, for instance, kinetics data, and then be required to determine the order of reaction and/or the rate constant using that set of data. In the second type you might be asked to design a laboratory procedure given a set of equipment/reagents to accomplish a certain task, such as separation of certain metal ions in a mixture. You must use the equipment given, but you do not have to use all of the equipment.

The third category of questions on the exam involves questions related to representations of atoms or molecules. These representations might include such things as Lewis structures, ball-and-stick models, or space-filling models. You might be asked to take one and convert it to another or to choose a particular representation that is the most useful in describing certain observations.

Your score on the free-response questions amounts to one-half of your grade and, as longtime readers of essays, we assure you that there is no other way to score highly than to know your stuff. While you can guess on a multiple-choice question and have a 1/5 chance of getting the correct answer, there is no room for guessing in this section. There are, however, some tips that you can use to enhance your FRQ scores.

1. Easy to read—easy to grade. Organize your responses around the separate parts of the question and clearly label each part of your response. In other words, do not hide your answer; make it easy to find and easy to read. It helps you and it helps the reader to see where you are going. Trust me: helping the reader can never hurt. Which leads me to a related tip … Write in English, not Sanskrit! Even the most levelheaded and unbiased reader has trouble keeping his or her patience while struggling with bad handwriting. (We have actually seen readers waste almost 10 minutes using the Rosetta stone to decipher a paragraph of text that was obviously written by a time-traveling student from the Egyptian Empire.)

2. Consistently wrong can be good. The free-response questions are written in several parts. If you are looking at an eight-part question, it can be scary. However, these questions are graded so that you can salvage several points even if you do not correctly answer the first part. The key thing for you to know is that you must be consistent, even if it is consistently wrong. For example, you may be asked to draw a graph showing a phase diagram. Following sections may ask you to label the triple point, critical point, normal boiling point, and vapor pressure—each determined by the appearance of your graph. So let’s say you draw your graph, but you label it incorrectly. Obviously, you are not going to receive that point. However, if you proceed by labeling the other points correctly in your incorrect quantity, you would be surprised how forgiving the grading rubric can be.

3. Have the last laugh with a well-drawn graph. There are some points that require an explanation (i.e., “Describe how …”) Not all free-response questions require a graph, but a garbled paragraph of explanation can be saved with a perfect graph that tells the reader you know the answer to the question. This does not work in reverse …

4. If I say draw, you had better draw. There are what readers call “graphing points” and these cannot be earned with a well-written paragraph. For example, if you are asked to draw a Lewis structure, certain points will be awarded for the picture, and only the picture. A delightfully written and entirely accurate paragraph of text will not earn the graphing points. You also need to label graphs clearly. You might think that a downward-sloping line is obviously a decrease, but some of those graphing points will not be awarded if lines and points are not clearly, and accurately, identified.

5. Give the answer, not a dissertation. There are some parts of a question where you are asked to simply “identify” something. This type of question requires a quick piece of analysis that can literally be answered in one word or number. That point will be given if you provide that one word or number whether it is the only word you write, or the fortieth. For example, you may be given a table that shows how a reaction rate varies with concentration. Suppose the correct rate is 2. The point is given if you say “2,” “two,” and maybe even “ii.” If you write a novel concluding with the word “two,” you will get the point, but you have wasted precious time. This brings me to …

6. Welcome to the magic kingdom. If you surround the right answer to a question with a paragraph of chemical wrongness, you will usually get the point, so long as you say the magic word. The only exception is a direct contradiction of the right answer. For example, suppose that when asked to “identify” the maximum concentration, you spend a paragraph describing how the temperature may change the solubility and the gases are more soluble under increased pressure, and then say the answer is two. You get the point! You said the “two” and “two” was the magic word. However, if you say that the answer is two, but that it is also four, but on Mondays, it is six, you have contradicted yourself and the point will not be given.

7. “How” really means “how” and “why.” Questions that ask how one variable is affected by another—and these questions are legion—require an explanation, even if the question doesn’t seem to specifically ask how and why. For example, you might be asked to explain how effective nuclear charge affects the atomic radius. If you say that the “atomic radius decreases,” you may have received only one of two possible points. If you say that this is “because effective nuclear charge has increased,” you can earn the second point.

8. Read the question carefully. The free-response questions tend to be multipart questions. If you do not fully understand one part of the question, you should go on to the next part. The parts tend to be stand-alone. If you make a mistake in one part, you will not be penalized for the same mistake a second time.

9. Budget your time carefully. Spend 1–2 minutes reading the question and mentally outlining your response. You should then spend the next 3–5 minutes outlining your response. Finally, you should spend about 15 minutes answering the question. A common mistake is to overdo the answer. The question is worth a limited number of points. If your answer is twice as long, you will not get more points. You will lose time you could spend on the remainder of the test. Make sure your answers go directly to the point. There should be no deviations or extraneous material in your answer.

10. Make sure you spend some time on each section. Grading of the free-response questions normally involves a maximum of one to three points for each part. You will receive only a set maximum number of points. Make sure you make an attempt to answer each part. You cannot compensate for leaving one part blank by doubling the length of the answer to another part.

You should make sure the grader is able to find the answer to each part. This will help to ensure that you get all the points you deserve. There will be at least a full page for your answer. There will also be questions with multiple pages available for the answer. You are not expected to use all of these pages. In some cases, the extra pages are there simply because of the physical length of the test. The booklet has a certain number of pages.

11. Outlines are very useful. They not only organize your answer, but they also can point to parts of the question you may need to reread. Your outline does not need to be detailed: just a few keywords to organize your thoughts. As you make the outline, refer back to the question; this will take care of any loose ends. You do not want to miss any important points. You can use your outline to write a well-organized answer to the question. The grader is not marking on how well you wrote your answer, but a well-written response makes it easier for the grader to understand your answer and to give you all the points you deserve.

12. Grading depends on what you get right in your answer. If you say something that is wrong, it is not counted against you. Always try to say something. This will give you a chance for some partial credit. Do not try too hard and negate something you have already said. The grader needs to know what you mean; if you say something and negate it later, there will be doubt.

13. Do not try to outthink the test. There will always be an answer. For example, in the reaction question, “no reaction” will not be a choice. If you find yourself doing this, pick the simplest answer. If you know the answer to a “difficult” question—give yourself credit for preparing well; do not think that it is too easy, and that you missed something. There are easy questions and difficult questions on the exam.

Questions concerning experiments will be incorporated into both the multiple-choice and free-response questions. This means that you will need to have a better understanding of the experiments in order to discuss not only the experiment itself, but also the underlying chemical concepts.

14. Be familiar with all the suggested experiments. It may be that you did not perform a certain experiment, so carefully review any that are unfamiliar in Chapter 19. Discuss these experiments with your teacher.

15. Be familiar with the equipment. Not only be familiar with the name of the equipment used in the experiment, but how it is used properly. For example, the correct use of a buret involves reading of the liquid meniscus.

16. Be familiar with the basic measurements required for the experiments. For example, in a calorimetry experiment you do not measure the change in temperature, you calculate it. You measure the initial and final temperatures.

17. Be familiar with the basic calculations involved in each experiment. Review the appropriate equations given on the AP exam. Know which ones may be useful in each experiment. Also, become familiar with simple calculations that might be used in each experiment. These include calculations of moles from grams, temperature conversions, and so on.

18. Other things to keep in mind:

• Begin every free-response question with a reading period. Use this time well to jot down some quick notes to yourself, so that when you actually begin to respond, you will have a nice start.

• The questions are written in logical order. If you find yourself explaining part C before responding to part B, back up and work through the logical progression of topics.

• Abbreviations are your friends. You can save time by using commonly accepted abbreviations for chemical variables and graphical curves. With practice, you will get more adept at their use. There are a number of abbreviations present in the additional information supplied with the test. If you use any other abbreviations, make sure you define them.