5 Steps to a 5: AP European History 2024 - Bartolini-Salimbeni B., Petersen W., Arata K. 2023

STEP 5 Build Your Test-Taking Confidence

AP European History Practice Exam 2 Answer Sheet

SECTION I, PART A

ANSWER SHEET

AP European History Practice Exam 2

SECTION I, PART A

Multiple-Choice Questions

Recommended Time—55 minutes

Directions: The multiple-choice section consists of 55 questions to be answered in a recommended time of 55 minutes. Each set of questions below refers to the written passage or figure that precedes it. Select the best answer for each question, and fill in the corresponding letter on the answer sheet supplied.

Questions 1—3 refer to the passage below.

Albeit the king’s Majesty justly and rightfully is and ought to be the supreme head of the Church of England, and so is recognized by the clergy of this realm in their convocations, yet nevertheless, for corroboration and confirmation thereof, and for increase of virtue in Christ’s religion within this realm of England, and to repress and extirpate all errors, heresies, and other enormities and abuses heretofore used in the same, be it enacted, by authority of this present Parliament, that the king, our sovereign lord, his heirs and successors, kings of this realm, shall be taken, accepted, and reputed the only supreme head in earth of the Church of England, called Anglicans Ecclesia; and shall have and enjoy, annexed and united to the imperial crown of this realm, as well the title and style thereof, as all honors, dignities, preeminences, jurisdictions, privileges, authorities, immunities, profits, and commodities to the said dignity of the supreme head of the same Church belonging and appertaining; and that our said sovereign lord, his heirs and successors, kings of this realm, shall have full power and authority from time to time to visit, repress, redress, record, order, correct, restrain, and amend all such errors, heresies, abuses, offenses, contempts, and enormities, whatsoever they be, which by any manner of spiritual authority or jurisdiction ought or may lawfully be reformed, repressed, ordered, redressed, corrected, restrained, or amended, most to the pleasure of Almighty God, the increase of virtue in Christ’s religion, and for the conservation of the peace, unity, and tranquility of this realm; any usage, foreign land, foreign authority, prescription, or any other thing or things to the contrary hereof notwithstanding.

English Parliament, Act of Supremacy, 1534

1. The English Parliament argued that the Act of Supremacy would do which of the following?

A. Give the English king a new position of authority

B. Give the position of head of the Church of England to Henry VIII alone and exclude his heirs

C. Establish Calvinism as the one true theology in England

D. End various forms of corruption plaguing the Church in England

2. The passage can be used as evidence for which of the following historical trends of the time period?

A. The consolidation of the power of the monarchy

B. The increased power of the Catholic Church

C. The increased piety of the nobility

D. The increasing religiosity of the masses

3. The Act was, in part, a way to do what?

A. An attempt to prevent the spread of Protestantism in England

B. An attempt to resolve Henry VIII’s financial difficulties

C. An attempt to legitimize Henry VIII’s only heir

D. An attempt to ally England with the Holy Roman Emperor

Questions 4—6 refer to the passage below.

Florence is more beautiful and five hundred forty years older than your Venice. . . . We have round about us thirty thousand estates, owned by nobleman and merchants, citizens and craftsman, yielding us yearly bread and meat, wine and oil, vegetables and cheese, hay and wood, to the value of nine thousand ducats in cash. . . . We have two trades greater than any four of yours in Venice put together—the trades wool and silk. . . . Our beautiful Florence contains within the city . . . two hundred seventy shops belonging to the wool merchant’s guild, from whence their wares are sent to Rome and the Marches, Naples and Sicily, Constantinople . . . and the whole of Turkey. It contains also eighty-three rich and splendid warehouses of the silk merchant’s guild.

Benedetto Dei, “Letter to a Venetian,” 1472

4. How was wealth in Renaissance Italy measured?

A. The size of landed estates

B. The number of estates owned by an individual

C. The monetary value of goods

D. The amount of gold held

5. The economy of Renaissance Florence was primarily based on which of the following?

A. Banking

B. The export of agricultural goods

C. War and conquest

D. The manufacture and export of wool and silk products

6. The passage may be used as evidence for the existence of which of the following Renaissance cultural characteristics?

A. Pride in the mastery of the military arts

B. Chivalry

C. Civic pride

D. Patronage of the arts

Questions 7—9 refer to the passage below.

First we must remark that the cosmos is spherical in form, partly because this form being a perfect whole requiring no joints, is the most complete of all, partly because it makes the most capacious form, which is best suited to contain and preserve everything; or again because all the constituent parts of the universe, that is the sun, moon and the planets appear in this form; or because everything strives to attain this form, as appears in the case of drops of water and other fluid bodies if they attempt to define themselves. So no one will doubt that this form belongs to the heavenly bodies. . . .

That the earth is also spherical is therefore beyond question, because it presses from all sides upon its center. Although by reason of the elevations of the mountains and the depressions of the valleys a perfect circle cannot be understood, yet this does not affect the general spherical nature of the earth. . . .

As it has been already shown that the earth has the form of a sphere, we must consider whether a movement also coincides with this form, and what place the earth holds in the universe. . . . The great majority of authors of course agree that the earth stands still in the center of the universe, and consider it inconceivable and ridiculous to suppose the opposite. But if the matter is carefully weighed, it will be seen that the question is not yet settled and therefore by no means to be regarded lightly. Every change of place which is observed is due, namely, to a movement of the observed object or of the observer, or to movements of both. . . . Now it is from the earth that the revolution of the heavens is observed and it is produced for our eyes. Therefore if the earth undergoes no movement this movement must take place in everything outside of the earth, but in the opposite direction than if everything on the earth moved, and of this kind is the daily revolution. So this appears to affect the whole universe, that is, everything outside the earth with the single exception of the earth itself. If, however, one should admit that this movement was not peculiar to the heavens, but that the earth revolved from west to east, and if this was carefully considered in regard to the apparent rising and setting of the sun, the moon and the stars, it would be discovered that this was the real situation.

Nicolas Copernicus, The Revolutions of the Heavenly Bodies, 1543

7. What belief distinguished Copernicus from the traditional, Aristotelian natural philosophers of his day?

A. The cosmos is spherical.

B. The Earth is spherical.

C. The cosmos is geostatic.

D. The Earth is not stationary.

8. Copernicus’s argument for a spherical cosmos was based on

A. observation and induction.

B. ancient textual authority.

C. experimentation.

D. deduction from first principles.

9. In which tradition was Copernicus working?

A. The Aristotelian tradition

B. The natural magic tradition

C. The skeptical tradition

D. The Platonic/Pythagorean tradition

Questions 10—11 refer to the passage below.

About the year 1645, while I lived in London . . . I had the opportunity of being acquainted with diverse worthy persons, inquisitive into natural philosophy, and other parts of human learning; and particularly of what has been called the “New Philosophy” or “Experimental Philosophy.” We did by agreements . . . meet weekly in London on a certain day, to treat and discourse of such affairs. . . . Our business was (precluding matters of theology and state affairs), to discourse and consider of Philosophical Enquiries, and such as related thereunto: as physics or physic[s], anatomy, geometry, astronomy, navigation, statics, magnetics, chemics, mechanics, and natural experiments; with the state of these studies, as then cultivated at home and abroad. We then discoursed of the circulation of the blood, the valves in the veins, the venae lactae, the lymphatic vessels, the Copernican hypothesis, the nature of comets and new stars, the satellites of Jupiter, the oval shape (as it then appeared) of Saturn, the spots in the sun, and its turning on its own axis, the inequalities and selenography of the moon, the several phases of Venus and Mercury, the improvement of telescopes, and grinding of glasses for that purpose, the weight of air, the possibility, or impossibility of vacuities, and nature’s abhorrence thereof, the Torricellian experiment in quicksilver, the descent of heavy bodies, and the degrees of acceleration therein; and diverse or divers[e] other things of like nature. Some of which were then but new discoveries, and others not so generally known and embraced, as now they are. . . .

We barred all discourses of divinity, of state affairs, and of news, other than what concerned our business of Philosophy. These meetings we removed soon after to the Bull Head in Cheapside, and in term-time to Gresham College, where we met weekly at Mr. Foster’s lecture (then Astronomy Professor there), and, after the lecture ended, repaired, sometimes to Mr. Foster’s lodgings, sometimes to some other place not far distant, where we continued such enquiries, and our numbers increased.

Dr. John Wallis, Account of Some Passages of his Life, 1700

10. The passage shows evidence for the development of which of the following?

A. An independent society for the study of natural philosophy in the seventeenth century

B. The study of natural philosophy in the royal courts in the seventeenth century

C. New universities for the study of natural philosophy in the seventeenth century

D. The study of natural philosophy in the Church in the seventeenth century

11. Wallis’s group was primarily interested in

A. undermining the traditional worldview.

B. creating a secular science to challenge the Church.

C. ascertaining the state of the New Philosophy in England and abroad.

D. the regulation of new knowledge so as not to undermine traditional values.

Questions 12—14 refer to the passage below.

[T]he the end and measure of this power, when in every man’s hands in the state of nature, being the preservation of all of his society, that is, all mankind in general, it can have no other end or measure, when in the hands of the magistrate, but to preserve the members of that society in their lives, liberties, and possessions, and so cannot be an absolute, arbitrary power over their lives and fortunes, which are as much as possible to be preserved, but a power to make law, and annex such penalties to them, as may tend to the preservation of the whole by cutting off those parts, and those only, which are so corrupt that they threaten the sound and healthy, without which no severity is lawful. And this power has its original only from compact, and agreement, and the mutual consent of those who make up the community. . . .

Whensoever, therefore, the legislative shall transgress this fundamental rule of society; and either by ambition, fear, folly or corruption, endeavor to grasp themselves, or put into the hands of any other, an absolute power over the lives, liberties, and estates of the people; by this breach of trust they forfeit the power the people had put into their hands for quite contrary ends.

John Locke, Two Treatises of Government, 1690

12. According to Locke, how did society and its legitimate government hold power over the members of society?

A. Divine right

B. The consent of those members of society

C. A covenant between the members of society

D. Conquest

13. Locke was an advocate of which political system?

A. Divine right monarchy

B. Absolutism

C. Constitutionalism

D. Socialism

14. According to Locke, how did a government lose its legitimacy?

A. When it is weak and can be overthrown

B. When the people wish to change governors

C. When it becomes corrupt

D. When it tries to exercise absolute power

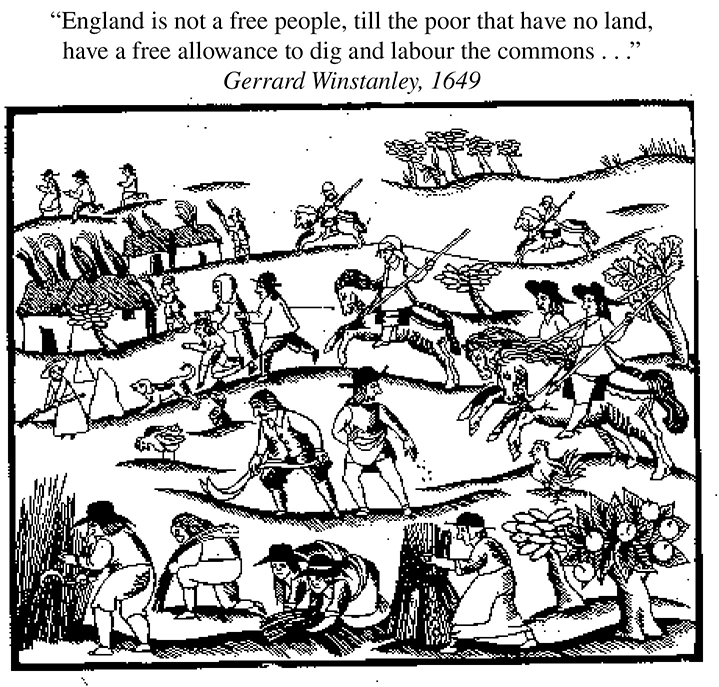

Questions 15 and 16 refer to the image below.

15. Who were Gerrard Winstanley and his Diggers resisting?

A. The king in the English Civil War

B. Parliament in the English Civil War

C. The enclosure movement

D. The institution of the three-field agricultural system

16. What actions did the Parliamentarian regime that was victorious in the English Civil War in 1649 take?

A. Parliament supported the efforts of Winstanley and the Diggers to return to old customs.

B. Parliament was determined to drive Winstanley and the Diggers off of all common land.

C. Parliament rewarded Winstanley and the Diggers for their previous support by awarding them use of the commons.

D. Parliament was indifferent to Winstanley and his movement.

Questions 17—19 refer to the passage below.

In a word, whoever will deign to consult common sense upon religious opinions, and will bestow on this inquiry the attention that is commonly given to any objects we presume interesting, will easily perceive that those opinions have no foundation; that Religion is a mere castle in the air. . . .

Savage and furious nations, perpetually at war, adore, under diverse names, some God, conformable to their ideas. . . . Madmen everywhere be seen who, after meditating upon their terrible God, imagine that to please him they must do themselves all possible injury. . . . The gloomy ideas more usefully formed of the Deity, far from consoling them under the evils of life, have everywhere disquieted their minds, and produced follies destructive to their happiness.

How could the human mind make any considerable progress, while tormented with frightful phantoms, and guided by men interested in perpetuating its ignorance and fears? . . . Occupied solely by his fears, and by unintelligible reveries, he has always been at the mercy of his priests, who have reserved for themselves the right of thinking for him and directing his actions. . . .

Let men’s minds be filled with true ideas; let their reason be cultivated. . . . To discover the true principles of morality, men have no need of theology, of revelation, or of gods.

Baron Paul d’Holbach, Good Sense, 1772

17. Which of the following best characterizes d’Holbach’s theological stance?

A. Atheist

B. Deist

C. Protestant

D. Catholic

18. d’Holbach was participating in which movement?

A. The later stages of the Protestant Reformation

B. The new political ideas of the early Enlightenment

C. The phase of the Enlightenment that called for “enlightened despotism”

D. The later, radical phase of the Enlightenment

19. Why can the passage be identified as part of the eighteenth-century cultural movement known as the Enlightenment?

A. It defends atheism.

B. It affirms the core Enlightenment ideals of reason and freedom of thought.

C. It offers a rational proof of the existence of God.

D. It uses satire to undermine orthodox ideas.

Questions 20 and 21 refer to the passage below.

The National Assembly, after having heard the report of the ecclesiastical committee, has decreed and do decree the following as constitutional articles:

Title I

IV. No church or parish of France nor any French citizen may acknowledge upon any occasion, or upon any pretext whatsoever, the authority of an ordinary bishop or of an archbishop whose see shall be under the supremacy of a foreign power, nor that of his representatives residing in France or elsewhere. . . .

Title II

I. Beginning with the day of publication of the present decree, there shall be but one mode of choosing bishops and parish priests, namely that of election.

II. All elections shall be by ballot and shall be decided by the absolute majority of the votes.

III. The election of bishops shall take place according to the forms and by the electoral body designated in the decree of December 22, 1789, for the election of members of the departmental assembly.

XXI. Before the ceremony of consecration begins, the bishop elect shall take a solemn oath, in the presence of the municipal officers, of the people, and of the clergy, to guard with care the faithful of his diocese who are confided to him, to be loyal to the nation, the law, and the king, and to support with all his power the constitution decreed by the National Assembly and accepted by the king.

Civil Constitution of the Clergy, July 12, 1790

20. According to the passage, what was the goal of the authors?

A. To reform the church of France along Protestant lines

B. To make the clergy of France subservient to the French government

C. To ensure that the clergy of France would be completely abolished

D. To make the clergy of France subservient to the Pope in Rome

21. Which of the following groups in France in 1790 would have been most likely to oppose the proclamations of this document?

A. Members of the National Assembly

B. Supporters of the king

C. Existing archbishops

D. Simple parish priests who cared deeply about their parishioners

Questions 22—24 refer to the passage below.

From this moment until that in which the enemy shall have been driven from the soil of the Republic, all Frenchmen are in permanent requisition for the service of the armies. The young men shall go to battle; the married men shall forge arms and transport provisions; the women shall make tents and clothing and shall serve in the hospitals; the children shall turn old linen into lint; the aged shall betake themselves to the public places in order to arouse the courage of the warriors and preach the hatred of kings and the unity of the Republic. . . .

The Committee of Public Safety is charged to take all necessary measures to set up without delay an extraordinary manufacture of arms of every sort which corresponds with the ardor and energy of the French people. It is, accordingly, authorized to form all the establishments, factories, workshops, and mills which shall be deemed necessary for the carrying on of these works, as well as to put in requisition, within the entire extent of the Republic, the artists and workingmen who can contribute to their success.

The representatives of the people sent out for the execution of the present law shall have the same authority in their respective districts, acting in concert with the Committee of Public Safety; they are invested with the unlimited powers assigned to the representatives of the people to the armies.

The Levée en Masse, August 23, 1793

22. This passage refers to the establishment of which of the following?

A. The French Republic

B. The Committee of Public Safety

C. War against the Coalition

D. Mass conscription

23. The passage is one example of the way in which the Committee of Public Safety

A. revamped the economy of the new French Republic.

B. successfully harnessed the human resources of the new French Republic.

C. reformed the religious rituals of the Church in the new French Republic.

D. brought about its own destruction.

24. Why could it be argued that what is discussed in the passage represents a turning point in the history of warfare in modern European history?

A. It represented the introduction of weaponry produced by large-scale industrialization.

B. It advocated the total extinction of a nation’s enemies.

C. It was war run by a committee.

D. It advocated total war.

Questions 25—27 refer to the passage below.

Many things combine to make the hand spinning of wool, the most desirable work for the cottager’s wife and children. A wooden wheel costing 2 s[hillings] for each person, with one reel costing 3 s[hillings] set up the family. The wool-man either supplies them with wool by the pound or more at a time, as he can depend on their care, or they take it on his account from the chandler’s shop, where they buy their food and raiment. No stock is required, and when they carry back their pound of wool spun, they have no further concern in it. Children from five years old can run at the wheel, it is a very wholesome employment for them, keeps them in constant exercise, and upright; persons can work at it till a very advanced age.

But from the establishment of the [mechanical] spinning machines in many counties where I was last summer, no hand work could be had, the consequence of which is the whole maintenance of the family devolves on the father, and instead of six or seven shillings a week, which a wife and four children could add by their wheels, his weekly pay is all they have to depend upon. . . .

I then walked to the Machines, and with some difficulty gained admittance: there I saw both the Combing Machine and Spinning Jenny. The Combing Machine was put in motion by a Wheel turned by four men, but which I am sure could be turned either by water or steam. The frames were supplied by a child with Wool, and as the wheel turned, flakes of ready combed Wool dropped off a cylinder into a trough, these were taken up by a girl of about fourteen years old, who placed them on the Spinning Jenny, which has a number of horizontal beams of wood, on each of which may be fifty bobbins. One such girl sets these bobbins all in motion by turning a wheel at the end of the beam, a wire then catches up a flake of Wool, spins it, and gathers it upon each bobbin. The girl again turns the wheel, and another fifty flakes are taken up and Spun. This is done every minute without intermission, so that probably one girl turning that wheel, may do the work of One Hundred Hand Wheels at the least. About twenty of these sets of bobbins, were I judge at work in one room. Most of these Manufactories are many stories high, and the rooms much larger than this I was in. Struck with the impropriety of even so many as the twenty girls I saw, without any woman presiding over them, I enquired of the Master if he was married, why his Wife was not present? He said he was not a married man, and that many parents did object to send their girls, but that the poverty of others, and not having any work to set them to, left him not at any loss for hands. I must do all the parties the justice to say, that these girls appeared neat and orderly: yet at best, I cannot but fear the taking such young persons from the eyes of their parents, and thus herding them together with only men and boys, must bring up a dissolute race of poor.

Observations . . . on the Loss of Woollen Spinning, c. 1794

25. What changes are described in the passage?

A. The shift from cottage industry organization to the mill system

B. The shift from agricultural work to industrial manufacturing

C. The shift from single country markets to international trade

D. The shift from individual labor to labor organized into trade unions

26. What does this passage say about spinning wool?

A. The work took very little time.

B. A family could make enough spinning to support the entire household.

C. The initial investment in equipment was quickly recouped.

D. The work was done only by girls.

27. What was one of the moral objections to mill work in the wool spinning industry?

A. That religious instruction was not provided to the young workers in the mills

B. That it promoted petty theft by desperate workers

C. That it broke down traditional gender roles by employing women and girls in a trade

D. That large numbers of young girls worked for unmarried men without parental supervision

Questions 28—30 refer to the passage below.

After as careful an examination of the evidence collected as I have been enabled to make, I beg leave to recapitulate the chief conclusions which that evidence appears to me to establish. As to the extent and operation of the evils which are the subject of this inquiry [the results indicate]:

That the various forms of epidemic, endemic, and other disease caused, or aggravated, or propagated chiefly amongst the labouring classes by atmospheric impurities produced by decomposing animal and vegetable substances, by damp and filth, and close and overcrowded dwellings prevail amongst the population in every part of the kingdom, whether dwelling in separate houses, in rural villages, in small towns, in the larger towns—as they have been found to prevail in the lowest districts of the metropolis. . . .

That the ravages of epidemics and other diseases do not diminish but tend to increase the pressure of population. . . . [In] the districts where the mortality is greatest the births are not only sufficient to replace the numbers removed by death, but to add to the population.

That the younger population, bred up under noxious physical agencies, is inferior in physical organization and general health to a population preserved from the presence of such agencies.

That the population so exposed is less susceptible of moral influences, and the effects of education are more transient than with a healthy population.

That these adverse circumstances tend to produce an adult population short-lived, improvident, reckless, and intemperate, and with habitual avidity for sensual gratifications.

Sir Edwin Chadwick, Inquiry into the Sanitary Condition of the Poor, 1842

28. According to the passage, what was one of the chief sources of disease in the poor areas of mid-nineteenth-century Britain?

A. A diet deficient in important nutrients and vitamins

B. Overcrowded living conditions and poor sanitation

C. A new wave of the Black Death

D. Unsafe working conditions

29. According to Chadwick’s report, what was the effect of rampant epidemic and disease on population pressure?

A. A decrease in population pressure was due to high mortality rates

B. No effect, because high mortality rates balanced out high birth rates

C. An increase in population pressure was due to higher birth rates

D. No effect, because population pressure and rates of epidemic and disease are unrelated

30. Mid-nineteenth-century reformers in Britain believed that unsanitary living conditions

A. produced a population of poor moral quality.

B. had no effect on the morality of the population.

C. caused disease.

D. improved moral values, as people had to struggle harder in their daily lives.

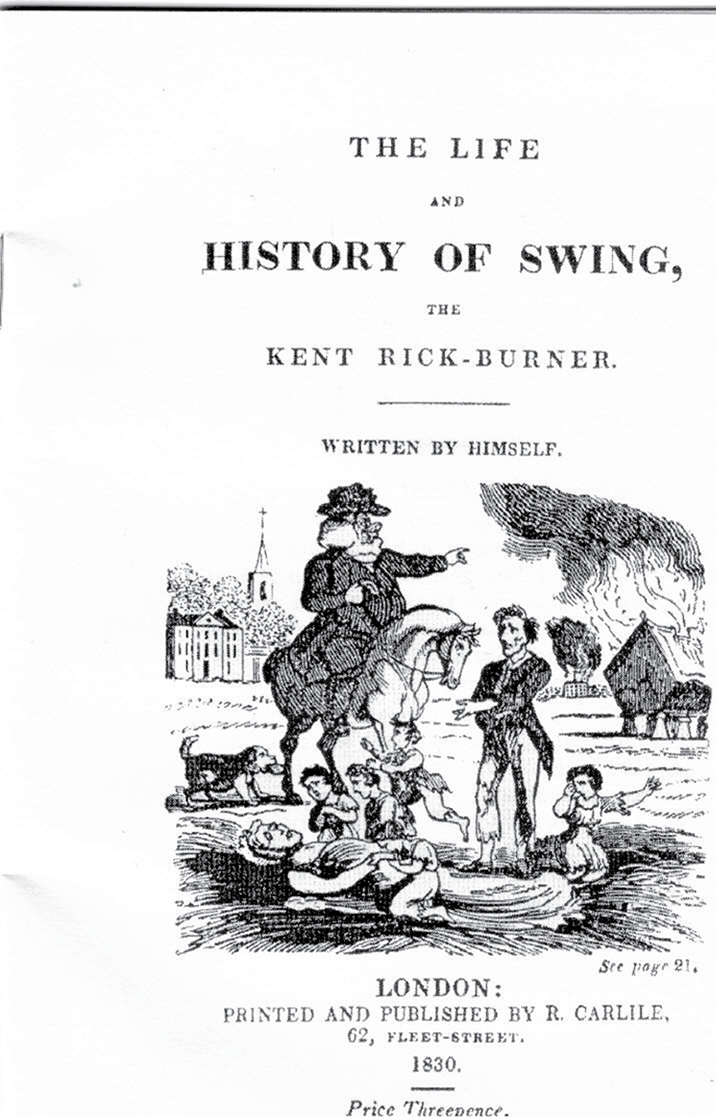

Questions 31 and 32 refer to the image below.

31. The image most likely refers to which of these events in 1830?

A. The death of King George IV of England and the ascension of William IV

B. The Swing Riots in Britain

C. The July Revolution in France

D. The Irish Potato Famine

32. What is the conflict depicted in the image?

A. One between factory owners and industrial workers

B. One between naval officers and sailors

C. One between agricultural and industrial interests

D. One between landlords and agricultural laborers

Questions 33 and 34 refer to the passage below.

Europe no longer possesses unity of faith, of mission, or of aim. Such unity is a necessity in the world. Here, then, is the secret of the crisis. It is the duty of every one to examine and analyze calmly and carefully the probable elements of this new unity. . . .

It was not for a material interest that the people of Vienna fought in 1848; in weakening the empire they could only lose power. It was not for an increase of wealth that the people of Lombardy fought in the same year; the Austrian Government had endeavored in the year preceding to excite the peasants against the landed proprietors, as they had done in Gallicia; but everywhere they had failed. They struggled, they still struggle, as do Poland, Germany, and Hungary, for country and liberty; for a word inscribed upon a banner, proclaiming to the world that they also live, think, love, and labor for the benefit of all. They speak the same language, they bear about them the impress of consanguinity, they kneel beside the same tombs, they glory in the same tradition; and they demand to associate freely, without obstacles, without foreign domination, in order to elaborate and express their idea; to contribute their stone also to the great pyramid of history. It is something moral which they are seeking; and this moral something is in fact, even politically speaking, the most important question in the present state of things. It is the organization of the European task. . . . The nationality of the peoples . . . can only be founded by a common effort and a common movement; . . . nationality ought only to be to humanity that . . . of a human group called by its geographical position, its traditions, and its language, to fulfil a special function in the European work of civilization.

Giuseppe Mazzini, On Nationality, 1852

33. According to Mazzini, what was the proper definition of a nation?

A. A kingdom with longstanding borders

B. A people with shared geography, language, and traditions

C. A people strong enough to avoid foreign domination

D. A people with a unified political ideology

34. Mazzini could best be described as influenced by which two ideological movements of the mid-nineteenth century?

A. Conservatism and nationalism

B. Socialism and nationalism

C. Romanticism and nationalism

D. Anarchism and socialism

Questions 35—37 refer to the passage below.

Yesterday Deputy Bamberger compared the business of government with that of a cobbler who measures shoes, which he thereupon examines as to whether they are suitable for him or not and accordingly accepts or rejects them. I am by no means dissatisfied with this humble comparison. . . . The profession of government in the sense of Frederick the Great is to serve the people, and may it be also as a cobbler; the opposite is to dominate the people. We want to serve the people. But I make the demand on Herr Bamberger that he act as my co-shoemaker in order to make sure that no member of the public goes barefoot, and to create a suitable shoe for the people in this crucial area. . . .

For it is an injustice on the one hand to hinder the self-defense of a large class of our fellow citizens and on the other hand not to offer them aid for the redress of that which causes the dissatisfaction. That the Social Democratic leaders wish no advantage for this law, that I understand; dissatisfied workers are just what they need. Their mission is to lead, to rule, and the necessary prerequisite for that is numerous dissatisfied classes. They must naturally oppose any attempt of the government, however well-intentioned it may be, to remedy this situation, if they do not wish to lose control over the masses they mislead. . . .

The whole problem is rooted in the question: does the state have the responsibility to care for its helpless fellow citizens, or does it not? I maintain that it does have this duty. . . . It would be madness for a corporate body or a collectivity to take charge of those objectives that the individual can accomplish; those goals that the community can fulfill with justice and profit should be relinquished to the community. [But] there are objectives that only the state in its totality can fulfill. . . . Among the last mentioned objectives [of the state] belong national defense [and] the general system of transportation. . . . To these belong also the help of persons in distress and the prevention of such justified complaints. . . . That is the responsibility of the state from which the state will not be able to withdraw in the long run.

Otto von Bismarck, “Reichstag Speech on the Law for Workers’ Compensation,” 1884

35. This passage most clearly shows the influence of which of the following trends in Europe in the second half of the nineteenth century?

A. The birth of constitutionalism

B. The blending of nationalism with liberalism

C. The birth of popular nationalism

D. The blending of nationalism with conservativism

36. In the passage, how is Bismarck attempting to portray his government?

A. As servants of the people

B. As absolute rulers

C. As leaders who deserve to be followed

D. As loyal opposition to the party in power

37. According to Bismarck, what was the role of the state?

A. To fulfill all social objectives that are worthy of being fulfilled

B. To fulfill no social objectives but rather leave them to private individuals and the community

C. To fulfill social objectives that have been demanded by the people

D. To fulfill social objectives that it alone can fulfill

Questions 38—40 refer to the image below.

38. In the image, Giuseppe Garibaldi is depicted as fitting the “boot of Italy” onto the leg of King Victor Emmanuel II of Piedmont-Sardinia. What does this say about the cartoonist’s beliefs?

A. He opposed Italian unification.

B. He favored Italian unification.

C. He believed Garibaldi to have had a significant role in bringing about the unification of Italy.

D. He believed that Count Cavour was most responsible for Italian unification.

39. What is the most likely date of the image?

A. Before June 1848

B. After June 1848

C. After October 1860

D. Before October 1860

40. How does the cartoonist view the unification of Italy generally?

A. He viewed the unification of Italy as coming to fruition.

B. He viewed the unification of Italy as doubtful.

C. He viewed the unification of Italy as a positive development.

D. He viewed the unification of Italy as a negative development.

Questions 41 and 42 refer to the passage below.

Confidential—For Your Excellency’s personal information and guidance

The Austro-Hungarian Ambassador yesterday delivered to the [German] Emperor [Wilhelm II] a confidential personal letter from the Emperor Francis Joseph [of Austria-Hungary], which depicts the present situation from the Austro-Hungarian point of view, and describes the measures which Vienna has in view. A copy is now being forwarded to Your Excellency. . . .

His Majesty desires to say that he is not blind to the danger which threatens Austria-Hungary and thus the Triple Alliance as a result of the Russian and Serbian Pan-Slavic agitation. . . . His Majesty will, furthermore, make an effort at Bucharest, according to the wishes of the Emperor Franz Joseph, to influence King Carol to the fulfillment of the duties of his alliance, to the renunciation of Serbia, and to the suppression of the Romanian agitations directed against Austria-Hungary.

Finally, as far as concerns Serbia, His Majesty, of course, cannot interfere in the dispute now going on between Austria-Hungary and that country, as it is a matter not within his competence. The Emperor Franz Joseph may, however, rest assured that His Majesty will faithfully stand by Austria-Hungary, as is required by the obligations of his alliance and of his ancient friendship.

Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg (chancellor of Germany), telegram to the German ambassador at Vienna, July 6, 1914

41. Which of the following best describes the context of Bethmann-Hollweg’s telegram?

A. Germany’s collaboration with Austria-Hungary during Germany’s unification process

B. The Balkan Question and the Triple Alliance

C. Germany’s rearmament in violation of the Treaty of Paris

D. Germany’s negotiations with Austria-Hungary and Italy to create the Triple Alliance

42. Why is Bethmann-Hollweg’s telegram often referred to as Germany’s “blank check”?

A. It pledged Germany to join the Triple Alliance and support Austria-Hungary against the Triple Entente.

B. It was understood to give Austria an unlimited scope of response to the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, to Serbia, and to Pan-Slavism within the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

C. It pledged Germany’s unlimited support to Franz Joseph in his efforts to succeed the recently assassinated Franz Ferdinand.

D. It offered nothing in terms of real support to Franz Joseph and Austria-Hungary.

Questions 43—45 refer to the passage below.

How has the war affected women? How will it affect them? Women, as half the human race, are compelled to take their share of evil and good with men, the other half. The destruction of property, the increase of taxation, the rise of prices, the devastation of beautiful things in nature and art—these are felt by men as well as by women. Some losses doubtless appeal to one or the other sex with peculiar poignancy, but it would be difficult to say whose sufferings are the greater, though there can be no doubt at all that men get an exhilaration out of war which is denied to most women. . . .

Men and women must take counsel together and let the experience of the war teach them how to solve economic problems by co-operation rather than conflict. Women [drawn into the workforce] have been increasingly conscious of the satisfaction to be got from economic independence, of the sweetness of earned bread, of the dreary depression of subjection. They have felt the bitterness of being “kept out”; they are feeling the exhilaration of being “brought in.” They are ripe for instruction and organization in working for the good of the whole. . . .

It would be wise to remember that the dislocation of industry at the outbreak of the war was easily met . . . because there was an untapped reservoir of women’s labor to take the place of men’s. The problems after the war will be different, greater, and more lasting. . . .

Because it will obviously be impossible for all to find work quickly (not to speak of the right kind of work), there is almost certain to be an outcry for the restriction of work in various directions, and one of the first cries (if we may judge from the past) will be to women: “Back to the Home!” This cry will be raised whether the women have a home or not. We must understand the unimpeachable right of the man who has lost his work and risked his life for his country, to find decent employment, decent wages and conditions, on his return to civil life. We must also understand the enlargement and enhancement of life which women feel when they are able to live by their own productive work, and we must realize that to deprive women of the right to live by their work is to send them back to a moral imprisonment (to say nothing of physical and intellectual starvation), of which they have become now for the first time fully conscious. And we must realize the exceeding danger that conscienceless employers may regard women’s labor as preferable, owing to its cheapness and its docility. . . . The kind of man who likes “to keep women in their place” may find he has made slaves who will be used by his enemies against him.

Helena Swanwick, “The War in Its Effect upon Women,” 1916

43. Which of the following best describes the context for Swanwick’s essay?

A. Possible social changes likely to occur with the coming of World War II

B. The effects of social changes that had occurred over a decade of warfare

C. The effects of social change being felt during the so-called Interwar Years

D. The social changes that were being experienced during World War I

44. According to the author, what would happen to women drawn into the workforce at the war’s conclusion?

A. Women would never be able to readjust to life at home.

B. Women would revolt against traditional social rules.

C. Women would face pressure to return to the home.

D. Women would be paid better than men because of the experience they had gained.

45. Swanwick surmised that some employers would be tempted to see women in what way?

A. As cheap and manageable alternatives to returning male labor

B. As unsuitable for a return to home life

C. As fair game for military service in the next war

D. As willing and able to work alongside men

Questions 46—47 refer to the passage below from the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk.

ARTICLE I: Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and Turkey for the one part, and Russia for the other part, declare that the state of war between them has ceased. They are resolved to live henceforth in peace and amity with one another. . . .

ARTICLE III: The territories lying to the west of the line agreed upon by the contracting parties, which formerly belonged to Russia, will no longer be subject to Russian sovereignty; the line agreed upon is traced on the map submitted as an essential part of this treaty of peace. The exact fixation of the line will be established by a Russo-German commission.

Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, March 14, 1918

46. How can the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk best be described?

A. As the result of the Bolsheviks’ need to end the Russian war effort in order to consolidate their revolutionary gains

B. As the result of corruption on the part of Bolshevik leaders and collaboration with Russian business interests

C. As the result of the breaking up of the Triple Entente

D. As the result of French and British aid being given to the so-called White Russians who opposed the Bolshevik government

47. What was the result of Article III of the treaty?

A. The surrender of the western part of the German Empire to the Russian Empire

B. The surrender of the eastern part of the German Empire to the Russian Empire

C. The surrender of the western part of the Russian Empire to the German Empire

D. The surrender of the eastern part of the Russian Empire to the German Empire

Questions 48 and 49 refer to the passage below.

Apart from the desire to produce beautiful things, the leading passion of my life has been and is hatred of modern civilization. What shall I say of it now, when the words are put into my mouth, my hope of its destruction—what shall I say of its supplanting by Socialism?

What shall I say concerning its mastery of and its waste of mechanical power, its commonwealth so poor, its enemies of the commonwealth so rich, its stupendous organization—for the misery of life! Its contempt of simple pleasures which everyone could enjoy but for its folly? Its eyeless vulgarity which has destroyed art, the one certain solace of labor? All this I felt then as now, but I did not know why it was so. The hope of the past times was gone, the struggles of mankind for many ages had produced nothing but this sordid, aimless, ugly confusion; the immediate future seemed to me likely to intensify all the present evils by sweeping away the last survivals of the days before the dull squalor of civilization had settled down on the world.

This was a bad lookout indeed, and, if I may mention myself as a personality and not as a mere type, especially so to a man of my disposition, careless of metaphysics and religion, as well as of scientific analysis, but with a deep love of the earth and the life on it, and a passion for the history of the past of mankind.

William Morris, How I Became a Socialist, 1896

48. By 1896, Morris had dedicated himself to what goal?

A. The spread of mechanical power in industry

B. The transformation of Britain into a commonwealth

C. The triumph of socialism

D. The spread of liberal democracy

49. What was Morris’s relationship to socialism?

A. He chose to become a socialist because he was appalled by the great waste of resources and general misery caused by modern society.

B. He chose to become a socialist because of the persuasiveness of Marx’s arguments.

C. He rejected socialism because it produced nothing but ugly confusion.

D. He rejected socialism because of a deep love of the earth and the life on it.

Questions 50 and 51 refer to the passage below.

The situation is critical in the extreme. In fact it is now absolutely clear that to delay the uprising would be fatal.

With all my might I urge comrades to realize that everything now hangs by a thread; that we are confronted by problems which are not to be solved by conferences or congresses (even congresses of Soviets), but exclusively by peoples, by the masses, by the struggle of the armed people. . . .

Who must take power? That is not important at present. Let the Revolutionary Military Committee do it, or “some other institution” which will declare that it will relinquish power only to the true representatives of the interests of the people, the interests of the army, the interests of the peasants, the interests of the starving.

All districts, all regiments, all forces must be mobilized at once and must immediately send their delegations to the Revolutionary Military Committee and to the Central Committee of the Bolsheviks with the insistent demand that under no circumstances should power be left in the hands of Kerensky [and his colleagues], . . . not under any circumstances; the matter must be decided without fail this very evening, or this very night.

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, known as Lenin, “Call to Power,” 1917

50. What was the immediate context of Lenin’s “Call to Power”?

A. Russia’s entrance into World War I

B. The onset of the February Revolution

C. Russia’s exit from World War I

D. The onset of the October Revolution

51. Which of the following did Lenin believe necessary?

A. The Russian military had to launch a new offensive.

B. Kerensky had to move immediately against the Bolsheviks.

C. The Bolshevik faction could wait no longer to seize power.

D. Only the Russian military could effectively govern Russia.

Questions 52 and 53 refer to the passage below.

In order to make the title of this discourse generally intelligible, I have translated the term “Protoplasm,” which is the scientific name of the substance of which I am about to speak, by the words “the physical basis of life.” I suppose that, to many, the idea that there is such a thing as a physical basis, or matter, of life may be novel—so widely spread is the conception of life as something which works through matter. . . . Thus the matter of life, so far as we know it (and we have no right to speculate on any other), breaks up, in consequence of that continual death which is the condition of its manifesting vitality, into carbonic acid, water, and nitrogenous compounds, which certainly possess no properties but those of ordinary matter.

Thomas Henry Huxley, “The Physical Basis of Life,” 1868

52. According to the passage, how did Huxley define “life”?

A. A force that works through matter

B. Essentially a philosophical notion

C. Merely a property of a certain kind of matter

D. A supernatural phenomenon

53. Huxley’s view is representative of which nineteenth-century ideology?

A. Anarchism

B. Materialism

C. Conservatism

D. Romanticism

Questions 54 and 55 refer to the passage below.

As a Jew, I have never believed in collective guilt. Only the guilty were guilty.

Children of killers are not killers but children. I have neither the desire nor the authority to judge today’s generation for the unspeakable crimes committed by the generation of Hitler.

But we may—and we must—hold it responsible, not for the past, but for the way it remembers the past. And for what it does with the memory of the past. In remembering, you will help your own people vanquish the ghosts that hover over its history. Remember: a community that does not come to terms with the dead will continue to traumatize the living.

We remember Auschwitz and all that it symbolizes because we believe that, in spite of the past and its horrors, the world is worthy of salvation; and salvation, like redemption, can be found only in memory.

Elie Wiesel, “Reflections of a Survivor,” 1987

54. What did Wiesel believe about the current generation of Germans?

A. They shared their ancestors’ guilt for the Holocaust.

B. They had a responsibility to remember the Holocaust.

C. They shared in the responsibility for the Holocaust.

D. They had no responsibility where the Holocaust was concerned.

55. Why did Wiesel assert that remembering the Holocaust was important?

A. It was necessary for the German people to become reconciled to their own history.

B. It hindered the healing process for the German people.

C. It would ensure that it never occurred again.

D. It would allow the Jews to forgive the German people.

Go on to Section I, Part B. ![]()

AP European History Practice Exam 2

SECTION I, PART B

Short-Answer Questions

Recommended Time—40 minutes

Directions: The short-answer section consists of three questions to be answered in a recommended time of 40 minutes. You must answer questions 1 and 2, but you may choose to answer either question 3 or question 4. Briefly answer ALL PARTS of each question. Be sure to write in complete sentences; outlines, phrases, and bullets will not be accepted.

Use the passage below to answer the questions that follow.

While the period witnessed a distinctive shift in ideas respecting gender relations at the level of social philosophy, away from a traditional idea of “natural” male supremacy towards a “modern” notion of gender equity, the process was vigorously contested and by no means achieved. Important legal, educational, professional and personal changes took place, but by 1901 full, unarguable gender equality remained almost as utopian as in 1800. If some notions of inequality were giving way to the idea that the sexes were “equal but different”, with some shared rights and responsibilities, law and custom still enforced female dependency. As women gained autonomy and opportunities, male power was inevitably curtailed; significantly, however, men did not lose the legal obligation to provide financially, nor their right to domestic services within the family.

Jan Marsh, 2001

1. Answer Parts A, B, and C.

a) Briefly explain ONE effect that the development of the separate spheres ideology had on women in the nineteenth century.

b) Briefly explain ANOTHER effect that the development of the separate spheres ideology had on women in the nineteenth century.

c) Briefly explain ONE reason for the emergence of the separate spheres ideology in the nineteenth century.

Use the passage below to answer the questions that follow.

Détente does not and cannot abolish the class struggle. No one can expect that under conditions of détente the communists will reconcile themselves to capitalist exploitation or that the monopolists will become revolutionaries. Thus the strict observance of the principle of non-interference in the affairs of other states, respect for their independence and sovereignty—this is the indispensable condition for détente.

We do not hide the fact that we see in détente the road to the creation of more favorable conditions of peaceful socialist and communist construction. This only goes to show that socialism and peace are inseparable.

Leonid Brezhnev, excerpts from a speech at the CPSU Congress, February 29, 1976

2. Answer Parts A, B, and C.

a) Briefly explain ONE reason why the passage can be identified with developments in the Cold War.

b) Briefly describe ONE factor that explains Brezhnev’s willingness to enter into détente with the United States during this period.

c) Briefly describe ANOTHER factor that explains Brezhnev’s willingness to enter into detente with the United States.

Answer either Question 3 or Question 4.

3. Answer Parts A, B, and C.

a) Identify ONE change in agricultural practices during the seventeenth century that contributed to the Industrial Revolution, and explain how it contributed to the Industrial Revolution.

b) Describe ONE social problem caused by the growing urbanization.

c) Explain ONE way in which governments tried to address the social problem.

4. Answer Parts A, B, and C.

a) Explain ONE factor that contributed to the New Imperialism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and explain how it contributed to the New Imperialism.

b) Explain ONE way in which indigenous populations resisted or attempted to resist Western European imperialism during this period.

c) Explain ANOTHER way in which indigenous populations resisted or attempted to resist Western European imperialism during this period.

End of Section I.

AP European History Practice Exam 2

SECTION II, PART A

Document-Based Question

Recommended Time—60 minutes

Directions: The following question is based on documents 1—7 provided below. (The documents have been edited for the purpose of this exercise.) The historical thinking skills that this question is designed to test include contextualization, synthesis, historical argumentation, and the use of historical evidence. Your response should be based on your knowledge of the topic and your analysis of the documents.

Write a well-integrated essay that does the following:

• States an appropriate thesis that directly addresses all parts of the question.

• Supports that thesis with evidence from all or all but one of the documents and your knowledge of European history beyond or outside of the documents.

• Analyzes the majority of the documents in terms of such features as their intended audience, purpose, point of view, format, argument, limitations, and/or social context as appropriate to your argument.

• Places your argument in the context of broader regional, national, or global processes.

Question: Evaluate the extent to which the attitudes concerning the value of empire were comparable in the nineteenth century.

Document 1

Source: William Rathbone Gregg, “Shall We Retain Our Colonies?” 1851

[Formerly,] our colonies were customers who could not escape us, and vendors who could sell to us alone.

But a new system has risen up, not only differing from the old one, but based upon radically opposite notions of commercial policy. We have discovered that under this system our colonies have cost us, in addition to the annual estimate for their civil government and their defense, a sum amounting to many millions a year in the extra price we have paid for their produce beyond that which other countries could have supplied to us. . . . [T]hey yield us nothing and benefit us in nothing as colonies that they would not yield us and serve us were they altogether independent.

Document 2

Source: Benjamin Disraeli, “Crystal Palace Speech,” 1872

Gentlemen, there is another and second great object of the Tory party. If the first is to maintain the institutions of the country, the second is, in my opinion, to uphold the empire of England. . . .

[W]hat has been the result of this attempt during the reign of Liberalism for the disintegration of empire? It has entirely failed. But how has it failed? Through the sympathy of the colonies with the mother country. They have decided that the empire shall not be destroyed, and in my opinion no minister in this country will do his duty who neglects any opportunity of reconstructing as much as possible our colonial empire, and of responding to those distant sympathies which may become the source of incalculable strength and happiness to this land. Therefore, gentlemen, with respect to the second great object of the Tory party also—the maintenance of the Empire—public opinion appears to be in favour of our principles. . . .

It cannot be far distant, when England will have to decide between national and cosmopolitan principles. The issue is not a mean one. It is whether you will be content to be a comfortable England, modelled and moulded upon continental principles and meeting in due course an inevitable fate, or whether you will be a great country—an imperial country—a country where your sons, when they rise, rise to paramount positions, and not merely obtain the esteem of their countrymen, but command the respect of the world. . . .

Document 3

Source: William Ewart Gladstone, “England’s Mission,” 1878

The honour to which the recent British policy is entitled is this: that from the beginning . . . to the end, the representatives of England, instead of taking the side of freedom, emancipation, and national progress, took, in every single point where a practical issue was raised, the side of servitude, of reaction, and of barbarism. . . .

Since [the Tory] accession to office, we have taken to ourselves . . . the Fiji Islands; the Transvaal Republic, in the teeth, it is now alleged, of the wishes of more than four-fifths of the enfranchised population; [and] the island of Cyprus. . . . [W]e have begun to protrude our military garrisons into our Indian frontier: in order to warn Russia how justly indignant we shall be if she should take . . . any corresponding step. . . .

I hold that to . . . overlook the proportions between our resources and our obligations, and above all to claim anything more than equality of rights in the moral and political intercourse of the world is not the way to make England great, but to make it morally and materially little.

Document 4

Source: John G. Paton, “Letter on New Hebrides Mission,” 1883

For the following reasons we think the British government ought now to take possession of the New Hebrides group of the South Sea islands, of the Solomon group, and of all the intervening chain of islands from Fiji to New Guinea:

1. Because she has already taken possession of Fiji in the east, and we hope it will soon be known authoritatively that she has taken possession of New Guinea at the northwest, adjoining her Australian possessions, and the islands between complete this chain of islands lying along the Australian coast.

2. The sympathy of the New Hebrides natives are all with Great Britain, hence they long for British protection, while they fear and hate the French, who appear eager to annex the group, because they have seen the way the French have treated the native races in New Caledonia, the Loyalty Islands, and other South Sea islands. . . .

3. All the men and all the money used in civilizing and Christianizing the New Hebrides have been British. Now fourteen missionaries and the Dayspring mission ship, and about 150 native evangelists and teachers are employed in the above work on this group, in which over £6000 yearly of British and British-colonial money is expended; and certainly it would be unwise to let any other power now take possession and reap the fruits of all this British outlay.

Document 5

Source: Jules François Camille Ferry, “Speech before the French Chamber of Deputies,” 1884

The policy of colonial expansion is a political and economic system . . . that can be connected to three sets of ideas: economic ideas; the most far-reaching ideas of civilization; and ideas of a political and patriotic sort.

In the area of economics, I am placing before you, with the support of some statistics, the considerations that justify the policy of colonial expansion, as seen from the perspective of a need, felt more and more urgently by the industrialized population of Europe and especially the people of our rich and hardworking country of France: the need for outlets [exports]. . . .

Gentlemen, we must speak more loudly and more honestly! We must say openly that indeed the higher races have a right over the lower races. . . . I repeat, that the superior races have a right because they have a duty. They have the duty to civilize the inferior races. . . .

I say that French colonial policy, the policy of colonial expansion, the policy that has taken us under the Empire [Napoleon III’s Second Empire], to Saigon, to Indochina, that has led us to Tunisia, to Madagascar—I say that this policy of colonial expansion was inspired by . . . the fact that a navy such as ours cannot do without safe harbors, defenses, supply centers on the high seas.

Document 6

Source: German newspaper advertisement, June 24, 1890

The diplomacy of the English works swiftly and secretly. What they created burst in the face of the astonished world on June 18th like a bomb—the German-English African Treaty. With one stroke of the pen—the hope of a great German colonial empire was ruined! Shall this treaty really be? No, no and again no! The German people must arise as one and declare that this treaty is unacceptable! . . . The treaty with England harms our interests and wounds our honor; this time it dares not become a reality! We are ready at the call of our Kaiser to step into the ranks and allow ourselves dumbly and obediently to be led against the enemy’s shots, but we may also demand in exchange that the reward come to us which is worth the sacrifice, and this reward is: that we shall be a conquering people which takes its portion of the world itself !

Document 7

Source: Captain F. D. Lugard, The Rise of Our East African Empire, 1893

It is sufficient to reiterate here that, as long as our policy is one of free trade, we are compelled to seek new markets; for old ones are being closed to us by hostile tariffs, and our great dependencies, which formerly were the consumers of our goods, are now becoming our commercial rivals. It is inherent in a great colonial and commercial empire like ours that we go forward or go backward. To allow other nations to develop new fields, and to refuse to do so ourselves, is to go backward; and this is the more deplorable, seeing that we have proved ourselves notably capable of dealing with native races and of developing new countries at less expense than other nations. . . .

A word as to missions in Africa. Beyond doubt I think the most useful missions are the medical and the industrial, in the initial stages of savage development. A combination of the two is, in my opinion, an ideal mission. . . . The “medicine man” is credited, not only with a knowledge of the simples and drugs which may avert or cure disease, but owing to the superstitions of the people, he is also supposed to have a knowledge of the charms and dawa which will invoke the aid of the Deity or appease His wrath, . . . The value of the industrial mission, on the other hand, depends, of course, largely on the nature of the tribes among whom it is located, . . . [W]hile improving the status of the native, [Industrial missions] will render his land more productive, and hence, by increasing his surplus products, will enable him to purchase from the trader the cloth which shall add to his decency, and the implements and household utensils which shall produce greater results for his labor and greater comforts in his social life.

Go on to Section II, Part B. ![]()

AP European History Practice Exam 2

SECTION II, PART B

Long-Essay Question

Recommended Time—40 minutes

Directions: Write an essay that responds to ONE of the following three questions.

Question 1: Evaluate the extent to which the political effects of nationalism on European civilization from 1789 to 1848 and 1866 to 1945 experienced change.

Question 2: Evaluate the significance of the context in which scientific work was done in the seventeenth century compared to that done in the nineteenth century.

Question 3: Evaluate the extent to which traditional imperialism (during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries) compared to New Imperialism (during the nineteenth century).

End of Practice Exam

![]() Answers and Explanations

Answers and Explanations

Section I, Part A: Multiple-Choice Questions

1. D. The passage refers to forms of corruption when it states that the Act would firmly establish the king’s “power and authority . . . to visit, repress, redress, record, order, correct, restrain, and amend all such errors, heresies, abuses, offenses” in the realm. A is incorrect because the passage states that the king is already “justly and rightfully . . . the supreme head of the Church of England,” and that the purpose of the Act is “for corroboration and confirmation” of that fact. B is incorrect because the passage clearly states that the position of head of the Church of England is established for both Henry VIII and “his heirs and successors, kings of this realm.” C is incorrect because the passage makes no reference to Calvinist theology and because the Church of England under Henry VIII did not espouse a Calvinist theology.

2. A. The passage is evidence of a monarch, with the aid of his Parliament, consolidating his power at the expense of the Church and its clergy. B is incorrect because the passage indicates that the Act is establishing power in the English monarchy at the expense of the Catholic Church. C is incorrect because the passage does not refer to any increase in piety on the part of the nobility. D is incorrect because the passage does not refer to any increase in religiosity on the part of the masses.

3. B. The passage states that the Act establishes Henry VIII’s right to “have and enjoy . . . all . . . profits, and commodities . . . of the same Church,” which went a long way toward solving his financial difficulties. A is incorrect because the passage makes no mention of preventing the spread of Protestantism and was, by establishing the Church of England’s independence from Rome, advancing the Protestant cause in England. C is incorrect because the passage makes no mention of legitimizing an heir and because Henry VIII had no male heir in 1534. D is incorrect because the passage makes no mention of an alliance with the Holy Roman Emperor.

4. C. The author boasts of the monetary value of the goods (“nine thousand ducats in cash”) produced on the estates of Florence. A is incorrect because the passage does not mention the size of the estates in Florence. B is incorrect because the passage does not mention the number of estates owned by any individuals. D is incorrect because the passage does not mention gold.

5. D. The passage refers to the large number of exports of wool and silk products. A is incorrect because the passage does not refer to banking. B is incorrect because the passage indicates that the production of agricultural products on the estates of Florence is for local consumption. C is incorrect because the passage does not refer to war and conquest.

6. C. The passage illustrates the author’s great pride in the achievements of his city. A is incorrect because the passage does not refer to the mastery of military arts. B is incorrect because the passage does not refer to the code of chivalry, which was a characteristic of medieval culture, not Renaissance culture. D is incorrect because, despite the fact that patronage of the arts was a Renaissance value, the passage does not mention it.

7. D. The passage argues that perception of motion is relative to the observer, and therefore it is possible that the Earth is in motion. A and B are incorrect because Copernicus’s assertion that the cosmos and the Earth are spherical is in agreement with the traditional, Aristotelian natural philosophers. C is incorrect because Copernicus is suggesting that the cosmos might not be geostatic.

8. A. The argument in the passage rests on observation (that the sun and moon are spherical and that water droplets are spherical) and an induction (that given the preponderance of bodies that are and strive to be circular, it is reasonable to conclude that the cosmos follows the general rule). B is incorrect because the passage makes no reference to ancient textual authority. C is incorrect because the passage makes no reference to experimentation. D is incorrect because the argument is inductive rather than deductive.

9. C. Copernicus’s willingness to question the traditional notion that the Earth was stationary is evidence that he was working in the skeptical tradition. A is incorrect because the passage offers evidence of Copernicus’s willingness to question the traditional, Aristotelian notion that the Earth was stationary. B is incorrect because nothing in the passage suggests that Copernicus was working in a tradition that believed in nature’s “hidden powers.” Though it is true that Copernicus is understood to have worked in the Platonic/Pythagorean tradition of searching for the underlying mathematical laws of the universe, D is incorrect because there is nothing in the passage that could be used as evidence for such an assertion.

10. A. The passage makes it clear that the group met outside of, and independent from, traditional institutions like universities, courts, and the Church. B is incorrect because the passage makes it clear that the group was not part of a royal court. C is incorrect because it is evident from the passage that the group was not part of an effort to form a new university. D is incorrect because the passage makes it clear that the group was not under the auspices of any church.

11. C. The passage states that the goal of the group was to know “the state of these studies, as then cultivated at home and abroad” and indicates that members helped to make this knowledge more readily available. A is incorrect because the passage makes no reference to the goal of undermining the traditional worldview. B is incorrect because the passage says that the group avoided issues of religion, but not that it was dedicated to challenging the Church. D is incorrect because the passage makes no reference to an attempt to regulate knowledge.

12. B. The passage explicitly states that “this power has its original only from compact, and agreement, and the mutual consent of those who make up the community.” A is incorrect because the passage does not refer to divine right, a concept that Locke wished to discredit. C is incorrect because the word Locke chooses is consent, which implies the possible withdrawal, rather than Hobbes’s word—covenant—which implied permanency. D is incorrect because the passage does not refer to conquest.

13. C. Locke’s expression of the preservation of the “lives, liberties, and possessions” of society’s members, of the limited nature of properly derived political power, and of the consent of the members of society as the origin of properly derived political power are all key concepts of constitutionalism. A is incorrect because the passage does not argue in favor of divine right monarchy. B is incorrect because the passage explicitly argues that properly derived political power cannot be arbitrary. D is incorrect because Locke’s emphasis on the protection of the property and possessions of society members is more in line with liberal constitutionalism than socialism.

14. D. The passage states that a government [legislature] forfeits its legitimacy when it “endeavor[s] to grasp themselves, or put into the hands of any other, an absolute power over the lives, liberties, and estates of the people.” A is incorrect because the passage does not state that a government loses legitimacy in moments of weakness. B is incorrect because the passage does not say that a government loses its legitimacy any time the people wish to make a change. C is incorrect because the passage does not say that instances of corruption equate to illegitimacy, only that corruption can be one motivation for a government seeking to exercise absolute power.

15. C. The illustration demands that people have access to the commons (common land), a custom that was being denied them through the enclosure of land. While the illustration dates from the era of the English Civil War, A and B are incorrect because the illustration does not indicate that Winstanley and the Diggers supported any particular faction. D is incorrect because the illustration does not refer to a three-field agricultural system.

16. B. The illustration shows the military force being used to expel Winstanley and the Diggers from the commons. A, C, and D are incorrect because the illustration shows the military force expelling Winstanley and the Diggers and not supporting them, awarding them lands, or showing indifference, respectively.

17. A. The passage expresses the atheist view that “men have no need of theology, of revelation, or of gods.” B is incorrect because a deist theology holds that God is necessary. C and D are incorrect because both Protestant and Catholic theologies begin with a belief in a necessary God.

18. D. Both the date of the passage and its advocacy of atheism locate it in the later, radical phase of the Enlightenment. A is incorrect because the date of the passage and its atheistic stance show that it is not a passage from the later stages of the Protestant reformation. B is incorrect because the passage offers a critique of religion, not political ideas. C is incorrect because the passage offers a critique of religion, not an argument for the need for an enlightened sovereign.

19. B. The passage affirms the core Enlightenment ideals of reason and freedom of thought by arguing for a rational critique of religious belief. A is incorrect because not all of the Enlightenment’s thought on religion and faith was atheistic. C is incorrect because the passage does not offer rational proof of the existence of God. D is incorrect because the passage is not satirical.

20. B. The passage indicates that the clergy of France are to be elected by the people of France, and that these clergy are to “be loyal to the nation.” A is incorrect because the passage makes no reference to Protestant theological reforms. C is incorrect because the passage refers to the election of clergy and their loyalty to the nation, not their complete abolishment. D is incorrect because the passage forbids the French people from recognizing clergy appointed by anyone foreign to France (which includes the pope) and because it commands French clergy to be loyal to the nation.

21. C. The existing archbishops owed their position to their contacts in Rome and ultimately to the pope. A is incorrect because the document expresses the will of the National Assembly that the clergy be brought under the auspices of the French state. B is incorrect because the document states that, henceforth, the clergy must be loyal to “the nation, the law, and the king,” and because a large number of the king’s supporters believed the independent power and wealth of the clergy needed to be curbed and brought under the authority of the state. D is incorrect because some simple parish priests sided with the National Assembly on this issue, believing that simple people would be given greater attention and care under a clergy that was elected and loyal to the French nation.

22. D. The document proclaimed that, by law, “all Frenchmen are in permanent requisition for the service of the armies.” A is incorrect because the French Republic was proclaimed to exist on September 22, 1792, nearly a year prior to the publication of the Levée en Masse. B is incorrect because the Committee of Public Safety was created in March 1793 by the National Convention and then restructured in July 1793; it was the Committee of Public Safety that authored the Levée en Masse. C is incorrect because France had declared war on the Habsburg monarchy of Austria on April 20, 1792, and the kingdom of Prussia joined the Austrian side a few weeks later. The Levée en Masse was a response to the needs of France in the face of war with the First Coalition, not a declaration of it.

23. B. The Levée en Masse is a good example of the way in which the Committee of Public Safety successfully harnessed the human resources of the new French Republic; it succeeded in training an army of about eight hundred thousand soldiers in less than a year, turning the tide of the War of the First Coalition in France’s favor. A is incorrect because the Levée en Masse does not deal with efforts to reform the economy of the new French Republic. C is incorrect because the Levée en Masse does not deal with efforts to reform the religious rituals of the Church. D is incorrect because the Levée en Masse, and the military success it brought, actually increased the popularity of the Committee of Public Safety.

24. D. It can be reasonably argued that the Levée en Masse was the first instance in modern European warfare where all elements of the population and all the reserves of the state were committed to a war effort. A is incorrect because the Levée en Masse did not introduce weaponry produced by large-scale industrialization. B is incorrect because the Levée en Masse did not advocate the total extinction of France’s enemies. C is incorrect because the War of the First Coalition continued to be run by French generals; the Levée en Masse simply increased the size and improved the training of the soldiers available to them.

25. A. The passage describes the effects on workers who spun thread in their homes for the textile trade as the mode of production shifted to more mechanized labor in a mill system. B is incorrect because the passage does not describe the effects of shifting from agricultural work to industrial manufacturing. C is incorrect because the passage does not discuss shifts in the textile markets, but rather in the mode of production. D is incorrect because the passage does not describe the effects of trade unions.