5 Steps to a 5: AP European History 2024 - Bartolini-Salimbeni B., Petersen W., Arata K. 2023

STEP 2 Understand the Skills That Will Be Tested

3 The Ways Historians Think

IN THIS CHAPTER

Summary: The AP European History Exam requires you to apply the thinking skills historians use. This chapter covers the skills you will need to be proficient in this type of thinking in order to do well on the exam. The second part of the chapter contains a new diagnostic exam, which you can use to determine your strengths and weaknesses.

Answers and explanations follow the exam.

Key Idea:

![]() The skills you will need to be proficient in applying can be grouped into three basic categories: (1) Reasoning chronologically, (2) Putting information in context, and (3) Arguing from evidence.

The skills you will need to be proficient in applying can be grouped into three basic categories: (1) Reasoning chronologically, (2) Putting information in context, and (3) Arguing from evidence.

Introduction

The AP European History Curriculum identifies interrelated sets of “Historical Thinking Skills” and requires students to apply one or more of them in each section of the exam. Your first task is to familiarize yourself with these skills and to understand how historians use them in creating a historical understanding of change over time.

There are many ways in which one might describe and categorize the intellectual skills employed by the historian. The simplest and clearest way for our purposes is to think of them as making up three interrelated thought processes: (1) Reasoning chronologically, (2) Putting information in context, and (3) Arguing from evidence.

Reasoning Chronologically

Chronology is the placing of events in the order in which they occurred. Once an accurate chronology has been constructed, reasoning based on that construction can begin.

Chronology and Causation

All historians seek, in one way or another, to explain change over time. One way to begin to do that is to create a chronology of events and then ponder cause and effect. For example, suppose we know the order of three events that occurred during the first year of World War I (WWI): the Russian Army invaded East Prussia (August 17, 1914); the German Army on the Eastern Front was put under new command and launched an attack against Russian forces (August 23—30, 1914); and Erich von Falkenhayn replaced Helmuth von Moltke as Chief of Staff of the German Army (September 14, 1914). Because we know the chronological order of these events, certain cause-and-effect relationships suggest themselves, whereas others are logically impossible. For example, because the change in command of the German forces on the Eastern Front and the German attack on Russian forces there occurred roughly a week after the Russian Army invaded East Prussia, it is a logical possibility that the Russian attack caused the Germans to react by changing command and counterattacking. Conversely, because the German decisions came roughly a week after the Russian attack, it is simply impossible for the German decisions to have caused the Russian attack.

Notice that, in our example, it is both the order in which the first two events occurred and the close proximity of the two events (both occurred in the same geographical area, and less than a week elapsed between the two events) that make the possibility of a cause-and-effect relationship between the two seem likely. Conversely, while it is possible that the first two events in our example caused the third (the change in overall command of the German Army from von Moltke to von Falkenhayn), the logical argument for a cause-and-effect relationship is weaker because of a lack of close proximity: the general commander was in charge of the entire war, and nearly a month had passed since those two events had occurred on the Eastern Front.

Correlation vs. Causation

Being able to show that a series of events happened in close proximity to one another (both chronologically and geographically) is to show that those events were correlated. However, it is important to understand that correlation does not necessarily imply causation. The fact that two events happened in close geographical or chronological proximity makes a cause-and-effect relationship possible, but not necessary; the close proximity could have been merely a coincidence. To establish a cause-and-effect relationship between two events, the historian must identify and use evidence. The use of evidence is part of the third set of skills identified by the AP European History Exam and is discussed below.

Multiple Causation

The sophisticated student of history understands that significant events in history usually have many causes. Accordingly, one looks for multiple causes in order to explain events. For example, if the historian discovers evidence (such as correspondence between high-ranking German Army officials) that supports the logical assertion that successful Russian incursions into East Prussia caused both a change in command for the Eastern Front and the decision to launch a counterattack, he or she still asks additional questions and looks for evidence of other contributing causes. What else was happening on the Eastern Front at that time? What did the overall German war effort look like at that time? What other considerations may have gone into those decisions?

Continuity

The historian recognizes that change does not come easily to people or to civilizations. Accordingly, the historian is sensitive to the persistence of certain forms of human activity (social structures, political systems, etc.). Sensitivity to the power of continuity forces the historian to ask questions about the forces that were strong enough to bring about change. For example, sensitivity to the power and importance of continuity in the way in which people live and work reminds the historian that a change from a localized and agriculturally oriented economy to an interconnected, commercial economy was neither inevitable nor even particularly likely. That realization sets the historian looking for the powerful forces that fostered those changes. Likewise, to understand and connect the periods being covered in AP European History, it is useful to look for patterns of cause and effect. Historian Jacques Barzun, in From Dawn to Decadence, said that study of the modern world discusses the “desires, attitudes, purposes behind . . . events or movements, some embodied in lasting institutions.” He characterized the four periods covered in AP European History as follows: 1450—1648—dominated by the issues of what to believe in religion; 1648—1815—what to do about the status of the individual and the mode of government; 1815—1914—the means by which one achieves social and economic equality; and 1914—present—the mixed consequences of all the previous efforts.

Comparison

When seeking to explain change over time, the historian often looks for patterns. Some patterns can be detected by asking basic questions, such as who, what, where, and when. For example, when seeking to understand the gradual and persistent shift from an agricultural economy to a commercial economy in Europe between the fourteenth and eighteenth centuries, the historian asks: What kinds of people tended to be in the vanguard of such change? Which type of work tended to change first? Did the changes occur simultaneously or follow a geographical progression? What type of economic activity changed first? The next step is to make comparisons. For example, the historian compares the nature of the changes that occurred in Britain to those that occurred in France and in the economies farther to the east. The comparisons reveal both similarities and differences, which the historian then explores, hoping to establish patterns of both change and continuity.

Contingency

Finally, the historian seeking to understand the cause-and-effect nature of historical events understands the role that contingency can play in human events. An event is said to be “contingent” if its occurrence is possible but not certain. The sophisticated student of history understands that there is a profound sense in which all significant events in history are contingent, because their occurrence depends on the action of human beings. For example, one of the most significant events in the history of the French Revolution is the storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789. On that day, a crowd stormed the notorious fortress in the heart of Paris, killed the guards who defended it, and paraded the severed heads of those guards around the city. Historians seeking to explain this event point to powerful forces, such as the politicization of the urban working people of Paris and their tremendous fear that the armies of their king, Louis XVI, would descend upon the city at any moment. But those same historians know that it was possible that the day could have gone very differently. They know that the crowd believed that there were many prisoners and an enormous amount of weapons inside the Bastille. They also know the crowd was mistaken; the only prisoner was the Marquis de Sade (and he was imprisoned for moral depravity, not political activity), and there were virtually no weapons inside the Bastille. These historians know, therefore, that the situation could have been defused; the guards could simply have abandoned the Bastille (the King’s cause would not have been harmed nor the Revolution’s cause helped). But the guards were young, inexperienced, and insecure; they panicked and fired into the crowd. Those completely unpredictable actions of the guards are the contingent causes of the storming of the Bastille.

Putting Information in Context

The historian must put every piece of information he or she encounters into its “proper context.” That means connecting that information to all of the relevant events or processes occurring at the time and place in which the source of the information was produced.

Constructing a Context for Past Events and Actions

The art of contextualization sounds complicated in the abstract, but in practice, it is really about asking additional, logical questions about a given event or action in the past. For example, one of the most notorious episodes in the history of conflict between England and Ireland is the massacring of the inhabitants of two Irish towns, Drogheda and Wexford, in September and October 1649, respectively. In the context of the English Civil War (1642—1649), Oliver Cromwell and his anti-Royalist army were sent to Ireland by the English Parliament to put down an anti-English rebellion that had been simmering there since 1641. Between September 2 and September 11, 1649, Cromwell and his army laid siege to the town of Drogheda. During the four days following Drogheda’s surrender, Cromwell oversaw the killing of some 4,000 of its people. Similarly, 2,000 more people were killed after the fall and surrender of the town of Wexford in October. Understandably, these events have earned Cromwell a reputation for a level of impulsive cruelty that is practically incomprehensible.

But making such actions comprehensible (constructing an understanding of how such a thing could occur) is precisely the task of the historian. To do it, the historian has to “put the events in their context,” or, more precisely, the historian has to construct a context around the event by asking further questions. In the case of Cromwell, historians have asked: Of the many other towns that Cromwell forced to surrender in his nine-month march through Ireland, how many times did he massacre a town’s inhabitants? The answer, interestingly, is none. Did Cromwell view the Irish who resisted merely as military enemies? No, Cromwell was among those within the Parliamentarian faction of the English Civil War who viewed themselves as “Saints,” whose mission was to purify the realm of false religions. Accordingly, Cromwell viewed the Catholic Irish not only as rebellious subjects, but as heretics. Was it unusual to kill large numbers of people after a successful siege? The rules of war at the time called for the inhabitants of a town to be spared, provided the governor of the town surrendered without a fight. Conversely, if the governor of a town decided to resist, he knew that he was putting the inhabitants at risk of retribution.

The historian uses the knowledge gained from asking and answering these contextual questions not to condone Cromwell’s actions, but to make sense of them. Once the Drogheda and Wexford massacres are put into context, they remain ghastly, but they are no longer incomprehensible. Cromwell may indeed have been impulsive and cruel, but he was not insane; there was a rationale behind his actions. He committed no more massacres in Ireland in 1649 because he did not need to. The governors of the other towns had seen the cruel consequences of resistance and surrendered without a fight.

Contextualization of Sources

Another aspect of historical thinking in which contextualization is important is in the use of sources. Historians build their understanding of past events and processes on the use of primary sources: all manner of artifacts that have come down to us from the times and places we wish to study. In order to gain an understanding of those sources—and to use them later as part of an interpretive argument—the historian must first put the sources in context. The process is similar to the one discussed above. The historian begins by asking a number of questions about the sources; the sum total of the answers to those questions makes up the context in which the sources must be interpreted.

For example, in the writing of her remarkable account of the English Civil War, the historian Diane Purkiss uncovered multiple primary sources offering eyewitness testimony to the events that occurred at Barthomley Church in Cheshire, England, in 1643. During the course of the English Civil War, Royalist troops arrived in the town of Barthomley, whose inhabitants were sympathetic to the Parliamentary side. One source that Purkiss uncovered asserts that the Royalist party encircled the church, where about 20 townspeople had taken refuge in the steeple. When the people would not come out, the source asserts, the Royalists set fire to the church, and when the people finally came out to escape the smoke and flames, the Royalists stripped them naked, abused them, and killed them. Another source confirms the report and asserts that it was one of many such instances in the area.

So, Purkiss has primary-source accounts that seem to corroborate each other, but Purkiss knows that even corroborating reports have to be put in context. Both sources, though produced independently of one another, are what is known as “newsbooks.” Such newsbooks were penned by Parliamentary sympathizers who were supplying “news” about the conflict. In short, Purkiss knows that such newsbooks were essentially Parliamentary propaganda, and that they cannot, therefore, be counted on as reliable accounts of what happened. Finally, it is frequently easier to place an event in context if you have a visual or literary back-up. At the end of this book, you will find a Resource Guide that contains both artistic and literary resources that will flesh out the historical picture.

Arguing from Evidence

The process of putting sources in context leads the historian directly to the art of arguing from evidence. For example, a historian would initially be tempted to argue that the existence of multiple primary sources asserting that an unprovoked massacre had been carried out by Royalist troops at Barthomley was proof that such a thing had occurred. However, by contextualizing those sources, Purkiss shows that such an argument will not hold up; the preponderance of evidence that shows that the contents of such newsbooks served as Parliamentary propaganda casts too much doubt on the reliability of those accounts.

But rather than give up on those sources, Purkiss asked herself what the historian could reliably learn from Parliamentary propaganda. Purkiss knew that the purpose of propaganda was to cultivate outrage at, and hatred of, the enemy. She knew, in other words, that propaganda aimed to play on the worst fears of its readers. So in order to learn something from those sources, Purkiss changed her question. Rather than asking, “What happened at Barthomley?” she asked, “What do the sources tell us about the fears of Parliamentary readers?” Because all of the newsbook accounts of the incident at Barthomley stressed setting fire to the church, stripping and abusing the people taken prisoner, and the murdering of those people, she concluded that it might be reasonable to assume that the greatest fears of people in that region during the conflict were the desecration of their holy places and the suffering and death of their loved ones at the hands of marauding soldiers. Finally, she went on to show that those fears did, in fact, mirror the major themes of atrocity stories in a large number of Parliamentary newsbooks.

Arguing from Evidence in an Essay

Let’s look at an example of how one argues from evidence. Suppose you were faced with the following question:

Explain ONE lasting effect of the Revolutions of 1848 on European political culture.

You might choose to answer with the following assertion:

The ultimate failure of the attempt, in the Revolutions of 1848, to bring about liberal, democratic reform in continental Europe caused a large portion of the European population to put their faith in conservative, rather than liberal, leaders.

Next, you would need to argue from evidence; that is, you would need to support and illustrate the assertion you have made by presenting and explaining events that serve as specific examples of what you have asserted. The result would look something like this:

In February 1848, the decision by King Louis Philippe to ban liberal reformers from holding public meetings led to massive street demonstrations in Paris. Demonstrations soon escalated into revolution, forcing Louis Philippe to abdicate and a new French republic (known as the Second Republic) to be established. The Assembly of the new republic attempted to establish a liberal, democratic constitution for the French Republic. However, in June of the same year, the French Army reestablished conservative control of Paris. An election in December swept the conservative Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte, nephew of Napoleon, to power. Three years later, he staged his own coup d’état, putting an end to the Second Republic.

Similarly, violence broke out in the major cities of the German kingdoms in the first half of 1848. In Berlin, Frederick William IV was forced to order the army out of the city and to agree to the formation of a parliament. In the wake of that victory, liberal leaders from all over Germany formed the Frankfurt Assembly and proclaimed that they would write a liberal, democratic constitution for a united Germany. But in the second half of 1848, Frederick William IV refused the Frankfurt Assembly’s offer to be the constitutional monarch of a united, democratic Germany, and instead used military troops to disperse the Assembly and to reassert conservative control in the cities. When, in November, troops moved back into Berlin, they faced little resistance. In the subsequent decades, popular support for German unification was given to Frederick William IV and his conservative chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, rather than to the liberals.

Developing Your Historical Thinking Skills

How do you cultivate and use historical thinking skills? Several steps will help you to do just that. Each one contributes to equipping you with the knowledge and attitudes that evolve into skills.

• Define terms. This is critical to understanding both chronology and context. Words change meaning and reflect the values of a given era. They separate fact and opinion.

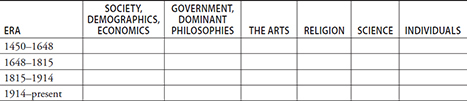

• Master the chronology of the period under study. This may be most easily done by “drawing” or charting things out.

It is important to remember to ask why, or, what leads from one era into the next?

• Develop guiding questions. For example, for the first era, you might ask: “How did the Reformation and Catholic (or Counter) Reformation act as an impetus to New World settlement?” “How did the Black Plague disrupt the socioeconomic order?” Or, for all eras: “How does the idea of the heroic change over time? What characteristics remain the same? What characteristics differ?” Try to explain a historical event or movement using only artworks or music or literature and the guiding question of authorial purpose: “How does artwork reflect changing attitudes about revolution or war?”

• Know the “cast of characters.” Each of the content-based chapters in this book (Chapters 9 to 25) begins with an overview or summary, followed directly by a list of key terms. Following each list are the names of (usually) between five and ten individuals closely associated with each content area. Some chapters have fewer names; some have many more. Your task is to become familiar with these people. Index cards are useful here, perhaps a differently colored one for each of the four AP European eras. For each individual, explain the role played, influence exerted, and legacies. If the person is famous for a written work, add the title of the work. The same holds true for works of art or music.

• Break the vacuum. History does not exist in a vacuum. It is made up of events, literature, music, art, philosophy, religion, science, economics, demographics, human and physical geography—in short, of multitudinous elements. At the end of this book, and at the end of each content chapter, are listings of resources to help you round out your command of historical facts. These resources include novels, plays, movies, the visual arts, and even YouTube videos. These can provide a break from your review of your textbook; however, these should supplement your textbook, not replace it.

Rapid Review

The AP European History Curriculum identifies interrelated sets of “Historical Thinking Skills.” Those skills can be categorized as follows:

• Reasoning chronologically

• Putting information in context

• Arguing from evidence

Reasoning chronologically is the practice of placing events in the order in which they occurred and then making reasonable inferences from that order about cause and effect. Putting information in context means connecting historical sources to all of the relevant events or processes occurring at the time and place in which the source was produced. Arguing from evidence is the art of making inferences and constructing a logical argument with specific examples.