Analysing English Grammar: A Systemic Functional Introduction (2012)

Chapter 1: Introduction to functional grammatical analysis

1.1 Introduction

People are interested in language and in understanding how we think language works for lots of different reasons. Becoming more knowledgeable about language often means having to learn something about grammatical analysis whether it is to teach children language skills, to work with those who have some kind of language difficulty or impairment, to teach a foreign language, or to master a command of a given language for a particular agenda such as speech writing or media communication. Understanding how language works means understanding how grammar works.

Grammar may seem like a very mysterious thing to many people. To use language, and even to use it well, we don’t really need to have an explicit understanding of it. However, if we want to work with language we need a way to talk about it and we need a way to identify the bits and pieces that it involves so that we can work with it more masterfully and more professionally.

There are many analogies for the kind of relationship we need to have with language when it becomes an object of study, but essentially we find the same distinction as with other walks of life where the lay person and professional differ in how they work with and talk about their area. I can walk and run but I’m not a professional athlete by any stretch of the imagination. I don’t need to know which muscles work when I need to use them. If something happened to my body – my knee, for example – I would see a professional and say something like ‘my knee hurts’. The relevant professional will know about the individual muscles and they will also understand what happened and how to fix the problem. Athletes and physiotherapists know what they need to do to maximize performance, and when they discuss these things together they use shared terminology to make communication work better. Similarly I can drive a car and I may be able to do basic repairs like change a tyre or replace a light bulb, but for most other problems I have to take my car to a professional mechanic. He or she knows all about how my car works, including the names of the various components of the engine and many other things that I am simply not aware of. If I wanted to be able to work with my car professionally (analyse and interpret it), I would need to learn about the components and how they interact, and in order to be able to talk about it with someone else I would also need the right terminology.

This is also true for becoming more professional about grammar. In order to be able to talk about it, we need some terminology so that we can be clear and precise. We also need to know how to recognize the relevant components and we need to learn about how they interact in language. This is why, with each chapter in this book, new terminology will be introduced along with the skills for recognizing the main grammatical components of the English language.

1.1.1 The motivation for this book

Most people I speak to either do not like grammar or they think they are not very good at it. They often say it is too difficult. This is an odd perspective because without knowing how our grammar works we would not be able to communicate – even if this knowledge remains largely unconscious and implicit. Negative attitudes towards grammar, like those towards mathematics, are unfortunately products of our education system and often depend on the attitudes of the teachers. These attitudes are damaging because we can be left with a sense that some are better at it than others, or, worse, that we just are not good at it. I usually ask my students whether they were ever taught grammar by a teacher who really loved it. Unfortunately the answer is rarely ‘yes’. This book is not about fixing that problem because it is not going to try to challenge the education system with respect to how English grammar is taught. However, what it will do is offer one way of approaching language from an analytical perspective and it will be presented by someone who really loves working with language. If you end up enjoying grammar even just a bit more than before then this book will have been a great success.

Having taught functional grammar for many years, I know there is a need for a book that concentrates on how to actually do the analysis, a systematic step-by-step procedure for analysing grammar. In presenting the practical ‘how-to’ aspects of analysis, this book draws from various existing descriptions of the theory of systemic functional grammar. Primarily, it relies on my own experience of teaching grammar. I offer one way to analyse grammar and there are of course other ways. I am convinced though that being consistent and systematic makes the job much easier.

Although the approach developed here falls within the framework of systemic functional linguistics generally, it isn’t trying to promote one single particular theoretical stance within systemic functional theory. Consequently, the book does not try to explain the theory in detail and the presentation draws on a variety of sources. Clearly the underlying theoretical framework has implications for the analysis but theoretical discussions are left aside wherever possible and, where appropriate, pointers are given for further reading on the topic.

1.1.2 Goals of the chapter

This chapter is very much an introductory overview of analysing grammar in a functional framework. It will explain why a functional approach is important but it will also emphasize that structure has to take a more prominent position in functional analysis than is the case in many existing books. The goal of this chapter is to lay the foundation for the functional–structural approach to analysis that is presented in the rest of the book. The remaining chapters cover individual topics in detail, so this chapter gives a bird’s-eye view of the functional view of language and what this kind of analysis looks like. It is a bit like looking at a photograph of a particular dish before starting to follow the instructions in the recipe. This way you get a glimpse of where we are headed before we dive into the details.

This chapter will also introduce some of the terminology used in this book. Each chapter will introduce more terms as we need them. Some terms will be capitalized just like personal names and place names. In principle, functional elements of the clause (such as Subject or Actor) will take a capital letter, which is standard practice in systemic functional linguistics. This is to remind us that these terms refer to a specific use of the term rather than the general meaning of the word in everyday use. It would be distracting to write every term with an initial capital letter, but hopefully this practice will help to reduce the potential for confusion between general words and specific terms for clausal elements.

1.1.3 How the chapter is organized

In the next section we will cover the basic principles of analysing grammar within a functional framework and explain why a functional–structural view of language is the most appropriate one for the analyst. Following this is a general overview of systemic functional linguistics. At the end of the chapter there are two sections for further practice and reading. First there are some short exercises for you to try, which will give you some practice working with language analysis. Then there is a section which gives you some indicators for further reading if you are interested in learning more about some of the ideas presented in this chapter.

1.2 Analysing grammar within a functional framework

All speakers of a language do something with it; they use language. They may play with it, shape it, but ultimately they use it for particular purposes. It serves a function. The ways in which people use language is always driven by the context within which people are using language and the speaker’s individual goals or objectives (conscious or subconscious). In this sense, we could say that language is primarily functional; in other words, for any language context (casual conversation, letter to the editor, political speech, etc.) language is being used to do a job for the speaker; it is being used by the speaker. On a day-to-day basis, it is the function of language that is most important to people using it. This is not to say that the form or structure of language is not important – it is. In many cases it is impossible to separate function and structure. Anyone who has tried to communicate with someone in an unfamiliar language or with a two–year-old will know that being grammatically correct is almost irrelevant. Meaning is what counts, and getting the right meaning is what is most important. By looking only at grammatical structure, we miss out on the important perspective we can gain by considering functional meaning. However, without a firm understanding of the grammar of language, or how language is structured, it is nearly impossible to analyse the functions of language effectively.

1.2.1 A functional–structural view of language

The problem we are faced with when we are analysing language is that we have to be able to segment it into sections first before we can complete the analysis. Otherwise it’s a bit like playing pin the tail on the donkey, where we hope that we’ve matched the right bits of language to the functional analysis. This is why a functional–structural approach is needed.

In order to try to prove this point, let’s consider a rather famous joke told by Groucho Marx. The example will probably work best if you haven’t already heard the joke.

This morning I shot an elephant in my pyjamas . . .

How he got into my pyjamas, I’ll never know!

What makes this example interesting is that it provides evidence of our ability to recognize functional and structural relations. Why does this joke work? It is based on the fact that the sentence is ambiguous; in other words it has more than one meaning or interpretation. However, the ambiguity is hidden because no one would recognize it initially. In the first part of the joke, the only understanding we have is that one morning while Groucho was still wearing his pyjamas, he shot an elephant. This sense corresponds to our real-world expectations because if there is a connection to be made amongst a man, pyjamas and an elephant, the association will be between the man and the pyjamas. So we understand immediately that the phrase in my pyjamas is telling us about how he (the speaker) shot an elephant. However, in the second part of the joke, we are forced to restructure our interpretation of the language used in order to form new relations and get a different meaning; we have to reinterpret what he said. By forcing a connection between the elephant and the pyjamas, we now understand that the elephant was wearing Groucho Marx’s pyjamas when he shot it. The function of in my pyjamas is now to describe the elephant. There was an inherent ambiguity in the first sentence that went unnoticed and this is where the humour comes in. It might make us laugh or maybe groan, but one thing the joke does very well is force us to reconsider how we grouped or structured the words in order to make meaningful relations. This is what is meant by grammar – how words and structures come together to make meaningful relations.

We need to be able to look at language analytically if we want to be able to understand how it is working. This means being able to identify the components and their groupings or relations and how they are functioning. Learning to analyse grammar in a functional framework requires a good understanding of the relationship between function and structure. This relationship is one we deal with on a regular basis. For example, we can consider this relationship by looking at what is probably our most common tool: the knife and fork.

Most of us will use these every day. There is an obvious relation between the shape or structure of each piece and the function it has. Without too much technical understanding, we appreciate that the structural representation (i.e. the form or shape) of these tools is well suited for their purpose and that this will have evolved over time. It is also possible to modify or adapt the form to fit the needs of the user: for example, a child’s fork has different relative dimensions and someone with arthritis may prefer to use an adapted shape. However, the general relation is that we use the fork to stab or hold food to raise it to our mouths and we use the knife to cut food. We could use the fork to cut and the knife to eat but generally this isn’t how we use these tools. So we can say that the main function of the knife is to cut food and that we need the tool to have form or a structure in order to do this.

Language is very similar. The function of language is what it is doing for the speaker (or rather what the speaker is doing with language) and in order to achieve this function, language is shaped into a structural form.

· Function is what language is doing (for the speaker).

· Structure is the form or shape of language and, specifically, how language is organized (by the speaker and determined by the language).

It is impossible to have one without the other. To ask which came first or which is more important is like asking whether the chicken or the egg came first. We need to accept that they work together. However, we stated above that, in terms of communication, we give priority (usually) to function or meaning.

The combination of function and structure gives us meaning. This is what lets us understand language and what lets us express what we want to say. Hopefully, the ‘elephant in my pyjamas’ example has proved this point. If we change the structural relation, we get a different meaning. The relationship between function and structure will be discussed in more detail in the next section.

1.3 An overview of systemic functional linguistics

Systemic functional linguistics (SFL), as its name implies, focuses on the functions of language. The system part of the name has to do with the way in which these functions are organized. The theory of SFL was developed originally by Michael Halliday in the late 1950s and early 1960s. There are some very good introductory descriptions of the theory and you will find references to these in the further reading section at the end of this chapter.

For Halliday, language is one type of semiotic system, which simply means that language is a system (or that it is organized systemically) and it represents a resource for speakers so they can create meaning. The view in SFL is that the ways in which we can create meaning through language are organized through patterns of use. The idea here is that language is organized as a system of options. This system organization is what enables speakers to create meaning, by selecting relevant options. The structure of language has a less prominent role in SFL since it is seen as ‘the outward form taken by systemic choices, not as the defining characteristic of language’ (Halliday and Matthiessen, 2004: 23). In other words, the primary driving force in language use is function but we need structure in order to express function. It is a complex relation which we will come back to throughout the book.

1.3.1 Functions of grammar

Function has an important place in SFL and is very much connected with the social uses of language. After all, language is primarily used for social communication. Halliday explains that ‘the internal organization of language is not arbitrary but embodies a positive reflection of the functions that language has evolved to serve in the life of social man’ (1976: 26). Therefore, at the foundation of SFL is the view of language as a social function.

The functions of language include both the use that language serves (i.e. how and why people use language) and linguistic functions (i.e. the grammatical and semantic roles assigned to parts of language). What is fundamental for Halliday is that language serves a social purpose. Therefore, his position is that a theory of linguistics must incorporate the functions of language in use.

1.3.1.1 Choice and meaning

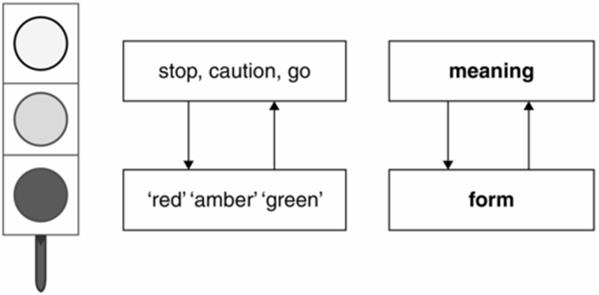

In systemic functional linguistics, language is viewed as a system and since it is a system which relates meaning to form, it is a system of signs. We are all familiar with sign systems since we encounter them all the time. A traffic light can be seen as an example of a very simple sign system. We all recognize three signs: [red light], [amber light] and [green light]. Each one means something different. The relationship between each meaning and sign (simplified for the purposes of this discussion) is shown in Figure 1.1. Basically this represents the whole system, which in this case involves only three semantic options: stop, caution and go.

Figure 1.1 Simple sign system

(adapted from Fawcett, 2008 and Eggins, 2004)

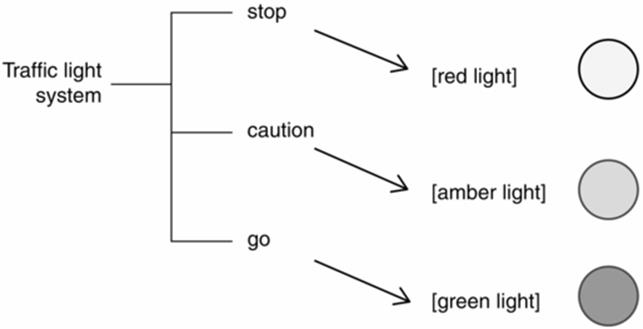

We can represent this relationship using system notation. This is generally how such systems are represented in SFL. An example of this is shown in Figure 1.2, where we find the meanings (stop, caution and go) along with their ‘realization’ or structural form: in other words, [red light], [amber light] and [green light]. The notation of the lines indicates that for this system of traffic control there are three options and you must select one of them. This is what we call an OR relation (i.e. select ‘stop’ OR ‘caution’ OR ‘go’). More complex systems may involve AND relations or combinations of both, as would be the case if, for example, we were trying to model the system of traffic flow for a given city.

Figure 1.2 Simple sign system in system notation

What this simple example also shows is the relation between function and structural form or what we will now call realization. We need to relate this explanation to our study of language. Function is what forms the basis of the organization of meaning in language but structure (linguistic expression) is needed to realize or convey the meaning. If there was no red light showing, how would we know to stop?

We can now think of language in two ways:

1. Language as system, a resource for communicating meanings to our fellow human beings. As a system it includes the full potential of the language.

2. Language as text, the realized output of the language system. As text (e.g. spoken, written), it is an instance of language in use.

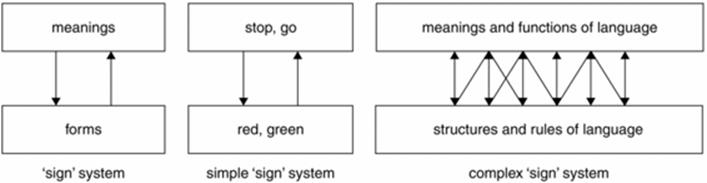

Language, when viewed as a system, is not a simple system as with the traffic light example, where each meaning maps onto one form. With language the relationship between meanings and forms is complex and there is not a one-to-one relationship, as Figure 1.3 attempts to show. This book will not be exploring this complexity or attempting to demonstrate it. We just need to accept that it is a complex relation. This isn’t a problem for what we are trying to achieve here because to do good analysis and to develop a good understanding of how language works we don’t really need to know everything there is to know about the theoretical representation of the language system.

Figure 1.3 Relation of meanings and forms in a semiotic (‘sign’) system

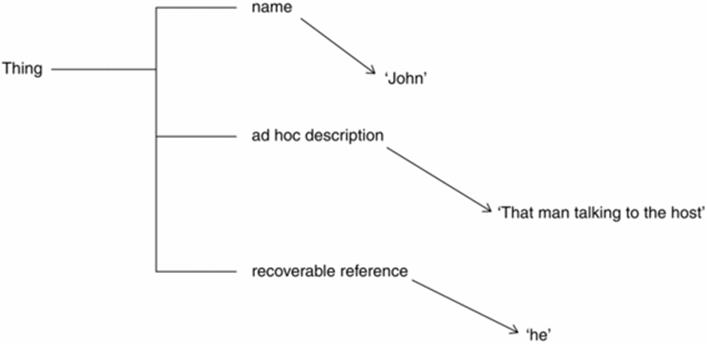

In SFL the relationship between meaning and form is one of realization. The various potential meanings in the language are represented as connected (or networked) systems. A system is simply a representation of a set of options. For example, when we want to refer to a person, we can do so in a variety of ways. One option is to refer to them by name if this seems appropriate, another option is to describe the person, and another option is to use a personal pronoun. As an example, imagine we are at a party and there is a man standing in the kitchen talking to the host and, in this scenario, I want to say something to you about that particular person. To illustrate the three options mentioned above, I might say one of the following: John works for the FBI; That man talking to the host works for the FBI; or He works for the FBI. How we refer to entities will be covered in detail in Chapter 3 but for the moment we can see that there are at least three options in English for how we can refer to someone: (1) using their name; (2) using a description (an ad hoc description); (3) using a personal pronoun (a recoverable reference). This set of options can be represented systemically as in Figure 1.4, where the system here indicates the three options illustrated in the examples above: John, that man talking to the host and he. The system is labelled ‘Thing’ (short for ‘referent thing’) because it covers the options for referring to a referent when the referent is a thing (people, objects, ideas, places, concepts, etc.).

Figure 1.4 An example of a system for Thing

There are three other considerations for the system representation of language in SFL. The first is that each system has what is called an entry condition. In other words, there is a condition that must be met for each system. In the system shown in Figure 1.4, the system can only be accessed when the language being produced concerns an entity of some kind (in this case a person). In SFL there is a system for every set of options being modelled in the language. Systems are networked, which means that they are all connected to some extent. The second consideration is that each system has what are called realization rules or statements, which make the connection between the option concerned and the way in which that option is realized in the language. For example it is not enough to simply describe what options are available to the speaker; there has to be some description of what this triggers in the language system. In the sample system shown in Figure 1.4, the selection of name will determine that a person’s name (for example, ‘John’) will be selected and used at that point. Finally the third consideration involves frequencies. This relates to the fact that certain options will be more or less frequent than others. In the sample system below, the option of recoverable reference is far more frequent than the other two. Recoverable reference involves the use of personal pronouns but these are only used if the speaker feels confident the addressee will be able to recover who is being referred to. For example, once the speaker has referred to a person by name (e.g. John works for the FBI, as above), they are highly unlikely to repeat the name to refer to this same person. Instead, the speaker is far more likely to use a pronoun (e.g. He lives in New York). In fact, a repeated name in most contexts will tend to cause confusion. However, in an example such as sentence (1) below, it is not at all clear who is being referred to for the second use of the personal pronoun, he. It is most likely that it is John who had the sinus infection and it is also most likely that it is the doctor who did the tests, but we can’t be sure who did the saying because it could be John or the doctor. However, what this example does show is that referring to a Thing is most commonly done by use of a recoverable reference such as the personal pronoun he. If we replace all pronouns by the relevant name, we quickly see that it sounds completely unnatural, as shown in example (2). Similarly, if we only used (ad hoc) descriptions, the text would sound equally odd, as in (3), but in this case it not only sounds odd, it causes confusion and could suggest that there was another person involved.The system notation is meant to explain language production from the perspective of the speaker. ‘Speaker’ is used in this book to include all instances of someone producing language (i.e. someone speaking or writing). As in the example above, it is the speaker who has to determine how to refer to the person they want to say something about. What we are interested in is analysing language and this is always language as text, the output of the language system (e.g. language that has been spoken or written). As analysts we are trying to pick apart and analyse language that has already been produced. In this book we won’t be focusing on the system networks at all except for illustrative purposes when appropriate, because discussing the system networks is really beyond what we can achieve in this book. We will try to develop a very basic understanding of what is meant by the system organization of the functions of language and how this relates to grammatical structure. In the further reading section at the end of this chapter, there are references to books which do explore the system networks in some detail. However, no books explore them fully for the same reason – they are simply too large to represent.

(1) John went to see the doctor and he did some tests and he also said he had a sinus infection. I’m glad he finally went

(2) John went to see the doctor and the doctor did some tests and John also said John had a sinus infection. I’m glad John finally went

(3) A man I know went to see the doctor and the doctor did some tests and the man also said the man had a sinus infection. I’m glad the man finally went

1.3.1.2 Function and context

So far we’ve talked about language output as text but text itself has not been defined and we won’t try to define it here. We’ll just consider, in vague terms, that text is the actual language expressed, for example by writing or speaking, and that it is expressed through chunks or units from the grammar of the language. The main unit of grammar that we are going to be focusing on in this book is the clause. The clause is a unit that is similar to the orthographic sentence. More will be said about this in Chapter 2 but for now we can just think of a clause as being more or less the same as a simple sentence.

The clause is a multifunctional unit of language. The grammatical functions are represented in the clause, and this means that each clause expresses more than one type of meaning. Halliday adopted a three-way view of linguistic functions, offering insight into what he considers to be the three main functional components of language.

The first type of meaning sees the clause as a representation of some phenomenon in the real world, and this is referred to as experiential meaning since it covers the speaker’s experience of the world. The experiential component serves to ‘express our experience of the world that is around us and inside us’ (Halliday, 1976: 27). This view is concerned with how speakers represent their experience. The notion of representing experience was further developed under the heading of the Ideational meaning, which includes experiential meaning as well as general logical relations. However, when discussing the various meanings of the clause, the logical is often left out. It won’t be dealt with in this book. There are references in the further reading section at the end of this chapter which offer detailed descriptions of the logical metafunction.

The second type views the clause as social interaction and reflects both social and personal meaning. It is referred to as interpersonal meaning. The interpersonal component expresses ‘the speaker’s participation in, or intrusion into, the speech event’ (1976: 27).

Finally, the third type of meaning relates the clause to the text and this is called textual meaning. However, the textual component, in Halliday’s view, is somewhat different from the other two as this function is ‘an integral component of the language system’ and he considers it to be ‘intrinsic to language’ since it has the function of creating text (p. 27).

To illustrate how these three meanings interact in the clause, I will use an example from my own experience. Last year on my birthday I was given a Jamie Oliver recipe book. Although this is probably not really news to write home about, I usually do email my family and friends about birthday-related events. Depending on who I was talking to and what my goal in communicating was, I might have said one of the following sentences. We can infer a different context and set of assumptions for each of the six sentences above. In all cases, the situation being described is one of someone giving me something for my birthday so we might be tempted to say that all of these sentences are saying the same thing, or that they mean the same thing, whereas in fact they all differ from each other with respect to the three types of meaning we just mentioned. In terms of experiential meaning (what is being represented), these examples are very similar. The first example is probably the fullest representation of what happened since it represents who gave the book, who received the book and why the book was given. Examples (5) and (9) differ most from the others in this sense because they do not represent the person who gave the book and the others do (even if in example (7), we don’t know who that person is). Examples (7) and (8) differ from the others when we consider how the language is being used to interact with the person being addressed. These sentences require a response, whereas the other sentences are simply giving information. Finally, we can recognize differences in textual meaning by looking at how the sentences begin and how they are each organized. Examples (4), (7) and (8) each begin by focusing on the person who gave the book but in (6), for example, the focus is on my birthday. We could go through each example in detail but what should be clear is that each example represents the same situation differently and each reflects a different social context.

(4) Kev gave me the new Jamie Oliver recipe book for my birthday

(5) I was given the new Jamie book for my birthday

(6) For my birthday, Kev gave me the new Jamie book

(7) Who gave me the Jamie book for my birthday?

(8) Kev gave me the Jamie book for my birthday, didn’t he?

(9) The recipe book was given to me for my birthday

By the end of this book, the analysis of these clauses will seem quite straightforward and the similarities and differences could be discussed in detail.

1.3.2 The multifunctional nature of the clause

The central unit of analysis in SFL is the clause. As discussed above, there are three main functional components to the grammar and these are integral to understanding the types of meaning identified in the clause. The components are referred to as metafunctions within SFL.

With the experiential component (or metafunction), the clause is seen as representation: the speaker’s representation of a particular situation involving particular processes and participants. The interpersonal component sees the clause as exchange: the speaker’s action and interaction with the addressee. Finally, with the textual component, the clause is seen as message: the speaker’s means of organizing the message and creating text. Each type of meaning expressed in the clause has associated to it specific systems which express the meaning potential of the grammar. The clause, as an instance of language, therefore holds traces of these meanings, which are recoverable through analysis.

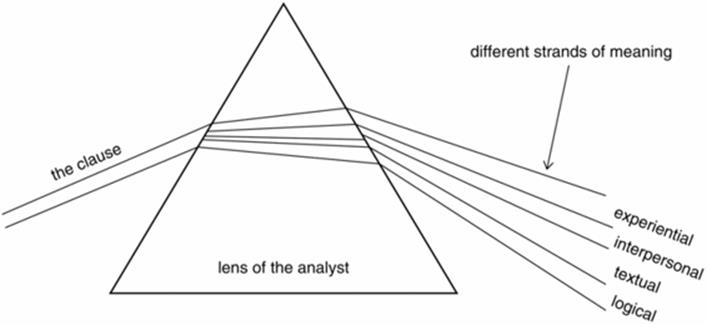

This is a good place to recall that there is a difference between the view of the metafunctions in language production and in language analysis. In producing language the speaker makes selections from the systems for the metafunctions in an integrated and simultaneous way; the meanings are brought together in one unit – the clause. The analyst tries to separate the metafunctions artificially in order to get a better understanding of the meanings represented in the clause. A useful image for this is that of the prism, which refracts white light into its component colours. In Figure 1.5, this imagery is used to show how the analyst views the clause in its component parts, even if, in real terms, the various strands are not really able to be separated from one another.

Figure 1.5 Analyst’s view of the clause

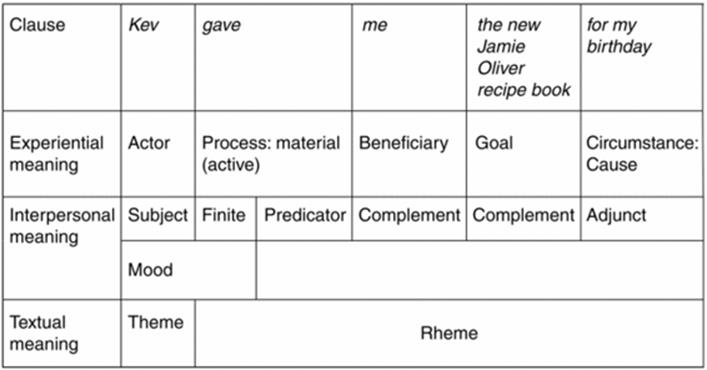

The three-strand analysis is illustrated in Figure 1.6, using example (4) from above (Kev gave me the new Jamie Oliver recipe book for my birthday). There is considerable terminology in Figure 1.6 and in this paragraph which will be unfamiliar to you. These will all be introduced in the relevant chapters. This example is simply to give you a glimpse of the multifunctional view of the clause that we will be developing in this book. In a sense the description in this example is an illustration of our goal in analysing the clause; this is what we want to achieve. As stated above, the experiential metafunction covers the range of processes and their participants. A very common process type is the material process, and the analysis shown in Figure 1.6 is an example of this. Each process type has specific participants associated to it. The most obvious of these for the material process is Actor, which represents the referent thing (person, place, object, concept, etc.) performing the process. One of the main functions of the clause within the strand of interpersonal meaning is that of Subject, which together with the Finite verbal element serves to determine the Mood structure of the clause. This is also illustrated in the example in Figure 1.6. Finally, the main element of relevance within the clause in terms of the textual metafunction is Theme, which functions as a means of ‘grounding what [the speaker] is going to say’ (Halliday and Matthiessen, 2004: 58). This is typically the very first part of the clause. Figure 1.6 shows how these three strands (or types) of meaning can be identified in a single clause.

Figure 1.6 Three-strand analysis of the clause in example (4)

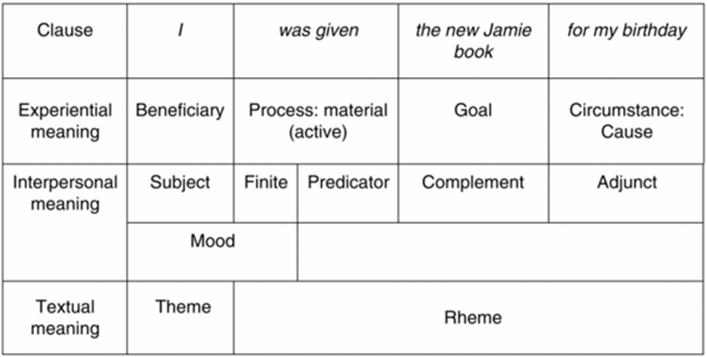

If we compare this clause to example (5) given above (I was given the new Jamie book for my birthday) as presented in Figure 1.7, we get a sense of how these two clauses are similar and how they are different. The Theme element of the clause is different in each case yet it is the first element in both cases. We can also see that what is missing or different in Figure 1.7 is that the Actor (Kev), the person who did the giving, is not represented. As we progress through each chapter, we will develop our understanding of the individual strands of meaning, but perhaps more importantly we will develop our skill at being able to identify the functional components of the clause.

Figure 1.7 Three-strand analysis of the clause in example (5)

It is important to note one important distinction to be made in this presentation of SFL. In both examples above, the meanings represented are those interpreted by the analyst as having been selected by the speaker. As analysts, we deduce the selection of options based on the instance presented. The description given in these diagrams is a kind of visual labelling of the functions of the various parts of the clause – it doesn’t help us to identify these parts and this is precisely the goal of this book, to equip the reader with the tools and strategies for analysing and segmenting the units. For example, how do we know that the new Jamie Oliver recipe book constitutes a unit? How do we know what the subject is?

What we need to be able to do is look at the internal structure of these units and determine confidently where the internal boundaries are within the clause. We also need a clear sense of how the group units work so that we can recognize their structure.

1.4 The goal of grammatical analysis

Everyone reading this book will have different reasons for wanting to get better at grammatical analysis. It might just be for fun. Playing around with language is fun and can be a bit like solving a tricky puzzle. For others it might be to improve their own language use, maybe to write better essays or be a better journalist. Some may be involved in teaching grammar and/or reading and writing skills. Perhaps you work with people who have difficulty with communication and want to develop your understanding of how grammar works so you can help them better. Those who carry out research on language (media texts, political commentary, etc.) may want to develop critical analytical skills in working with language. The goal of grammatical analysis will always depend on the purpose of the investigation. Ultimately, however, the goal of functional grammatical analysis is to gain a deeper understanding of language in use and an insight into language use that would not be possible without this kind of in-depth analysis. As Halliday (1973: 57) explains, ‘the essential feature of a functional theory is not that it enables us to enumerate and classify the functions of speech acts, but that it provides a basis for explaining the nature of the language system, since the system itself reflects the functions that it has evolved to serve’.

Regardless of the particular goals a researcher may have, the approach and process are the same. Of course the selection of the data or texts is also dependent on the research goals but grammatical analysis itself does not rely on a particular objective. It is important, however, to know what problem or question you want to answer as this will lead the focus of the research. As previously stated, the goal of this book is to develop the skills and procedures for general grammatical analysis within a functional framework.

1.4.1 The organization of the book

The organization of this book is intended to build up the approach to grammatical analysis being presented here. In Chapter 2, the focus is on identifying the main units of the clause and on recognizing groups and lexical items. Chapter 3 offers a description of the nominal group, analysing simple structures at first and then moving to increasingly challenging complex expressions. Then Chapter 4 contributes to the knowledge gained in the previous chapters by considering the clause as a whole. It deals specifically with the problems of analysing experiential meaning in the clause. The topic of Chapter 5 is understanding how the clause is used in interactions. It concentrates on the verbal system in English and how to identify the Subject and verbal elements of the clause. Chapter 6 covers the textual functions of the clause, discussing how to identify thematic elements in the clause including constructions that are more challenging. Having completed the internal view of the clause, Chapter 7 explains how to segment text into clause units by recognizing the boundaries of the clause within a text. Chapter 8 presents a complete step-by-step guide to analysing language. It is essentially a summary of the previous chapters, listing the steps for the analysis of an individual clause. Finally Chapter 9 demonstrates how the analysis of clauses reveals the meanings in the text. The answers to all exercises are given in Chapter 10.

1.5 Exercises

Exercise 1.1 Clause recognition exercise

The two texts below, Text 1.1 and Text 1.2, are reproduced here without any punctuation. Your job is to punctuate them as best you can, trying to identify individual sentences. In doing so, you will be indicating where you think the clause boundaries are. What this exercise will do is access your unconscious knowledge about the main grammatical units of language. It may help to read it aloud. Once you have finished, try to answer these questions. How did you know where to put punctuation? What criteria did you use? Was one text easier to punctuate than the other? What can you tell about the social context of each text? How were you able to recognize this?

Text 1.1

hello there how are you how are you managing with work school and the boys are you finding time for yourself at all again sorry I have been so long in getting back to you work has been crazy too I always feel like I am rushing so now when I feel that I try and slow myself down I also have the girls getting more prepared for the next morning the night before and that has seemed to help the mornings go more smoothly I will be glad when we don’t have to bother with boots hats and mitts the days are getting longer so hopefully it will be an early spring

Text 1.2

this module aims to offer an introduction to a functionally oriented approach to the description of the English language and to provide students with an understanding of the relationship between the meanings and functions that are served by the grammatical structures through which they are realized the major grammatical systems will be explored through a functional framework at all stages the description and analysis will be applied to a range of text types by so doing we will be able to explore both the meaning potential that speakers have and how particular choices in meaning are associated with different texts

link to answer

Exercise 1.2

Consider the two statements given below. Compare the underlined sections in statement A and statement B. Do you feel each speaker is saying approximately the same thing? If so, how are they similar and, if not, in what ways do they differ?

A Tony Blair, Special Conference (Labour Party). 29 April 1995.

I wasn’t born into this party. I chose it. I’ve never joined another political party. I believe in it. I’m proud to be the leader of it and it’s the party I’ll always live in and I’ll die in.

link to answer

B Nick Clegg, Liberal Democrat Party. 19 October 2007.

Like most people of my generation, I wasn’t born into a political party. I am a liberal by choice, by temperament and by conviction. And when I talk to the people I represent, I become more convinced every day that only liberalism offers the answers to the problems they face.

link to answer

link to answer

1.6 Further reading

On the functions of grammar:

Fawcett, R. 2008. Invitation to Systemic Functional Linguistics through the Cardiff Grammar: An Extension and Simplification of Halliday’s Systemic Functional Grammar. 3rd edn. London: Equinox.

Halliday, M. A. K. 1994. An Introduction to Functional Grammar. 2nd edn. London: Arnold.

Other relevant introductory textbooks:

Bloor, T. and M. Bloor. 2004. The Functional Analysis of English: A Hallidayan Approach. 2nd edn. London: Arnold.

Coffin, C., J. Donohue and S. North. 2009. Exploring English Grammar: From Formal to Functional. London: Routledge.

McCabe, A. 2011. An Introduction to Linguistics and Language Studies. London: Equinox.

Thompson, G. 2004. Introducing Functional Grammar. 2nd edn. London: Arnold.

On grammatical structure:

Fawcett, R. 2008. Invitation to Systemic Functional Linguistics through the Cardiff Grammar: An Extension and Simplification of Halliday’s Systemic Functional Grammar. 3rd edn. London: Equinox.

Fawcett, R. 2000c. A Theory of Syntax for Systemic Functional Linguistics. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Morley, D. G. 2000. Syntax in Functional Grammar. London: Continuum.

On system networks:

Fawcett, R. 2008. Invitation to Systemic Functional Linguistics through the Cardiff Grammar: An Extension and Simplification of Halliday’s Systemic Functional Grammar. 3rd edn. London: Equinox.

Halliday, M. A. K. and C. Matthiessen. 2004. An Introduction to Functional Grammar. 3rd edn. London: Hodder Arnold.