Analysing English Grammar: A Systemic Functional Introduction (2012)

Chapter 5: Orienting language

5.1 Introduction

The previous chapter was concerned with exploring how speakers represent their experience through language. This included the various representations of processes, participants and circumstances and how these elements could be configured in meaningful ways. In addition to this, language also has a primary social function; how people interact through language. Most instances of language use will involve both experiential representation and personal interaction. These two functions tend to be so closely connected that it is very difficult to isolate them. In systemic functional linguistics, the main strands of meaning are considered to be created simultaneously. It is therefore artificial to separate the strands completely but we will pursue this and try to keep them isolated in the discussions here in order to gain explanatory power. It is easy to focus on the particular meaning associated to each strand of meaning as we consider each of the three main metafunctions in turn.

Having completed the presentation of experiential meaning in Chapter 4, this chapter concentrates on interpersonal meaning; the meanings created from the speaker’s personal ‘intrusion’ on the language situation (Halliday, 1978: 46) and how the speaker uses language to interact with others. This involves the means by which the speaker’s personal views are expressed, such as, for example, degrees of doubt, certainty, ability or obligation. In addition to these more personal meanings, speakers also express meanings that involve interaction more explicitly, such as asking questions, giving instructions or providing information.

To illustrate this, we will take a look at a brief exchange that took place on Sky Sports recently. It was originally a private conversation between two presenters which ended up being broadcast publicly and, because of the controversial content of the conversation, it drew considerable media attention. An excerpt from this conversation is given below in Text 5.1. The two presenters are Mr Keys and Mr Gray, both employees of Sky Sports at the time. As a result of these comments, Mr Gray was fired and Mr Keys resigned. The context for this conversation involves discussion between the two employees before presenting the Liverpool versus Wolves football match on 22 January 2011. They were discussing the female assistant referee who was going to be one of the referees for the match which they were presenting.

Text 5.1 Excerpt from Sky Sports presenters

MR GRAY: Can you believe that? A female linesman. Women don’t know the offside rule.

MR KEYS: Course they don’t. I can guarantee you there will be a big one today. Kenny will go potty. This isn’t the first time, is it? Didn’t we have one before?

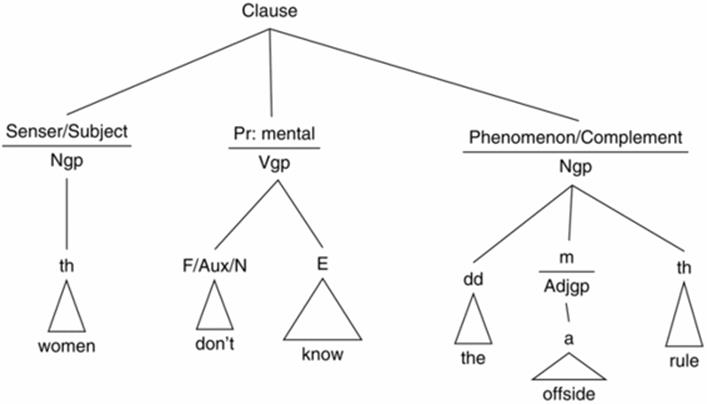

The brief example in Text 5.1 represents the experience of each speaker. Based on the previous chapter, we should be able to recognize some mental processes (e.g. believe, know) and relational processes (e.g. be, have). There are also various participants represented in relation to these processes; for example, Senser (you, women) and Phenomenon (that, the offside rule); Carrier (this) and Attribute (the first time). However, what is hopefully also clear is that, in addition to the content represented, language is being used to interact as well. The speakers are asking questions and responding to each other. In addition we also get a sense of their opinions.

In this chapter, we want to add to the experiential description of the clause developed in Chapter 4 by incorporating the main functions of the interpersonal strand of meaning. In doing so, the focus will be on the elements of the clause which are contributing to the meanings of personal and interpersonal interaction.

5.2 Goals and limitations of the chapter

Each strand of meaning is expansive and, consequently, the presentation of its features and functions is selective. The goal for this chapter is to explain the main functional elements of interpersonal meaning in terms of their recognition. In other words, keeping in line with the functional–structural view taken in this book, the focus will be on how to analyse interpersonal functions by recognizing their structural form.

This chapter will focus on the core functional elements of interpersonal meaning, including Subject, Finite and Mood. There are many very good textbooks which give considerable detail about other functions such as speech roles (or the role of the clause in the communicative exchange), and a list of suggested reading will be given in section 5.11 as a supplement to this chapter.

The chapter is organized as follows. The next section will concentrate on the Subject element of the clause and consider what its role is and how to recognize it. Then, in section 5.4 the verbal system in English is presented with particular focus on the Finite verbal element of the clause and the distinction between finite and non-finite clauses. Once the Subject and Finite elements have been covered, sections 5.5 and 5.6 will offer a brief presentation of modality and polarity respectively. In section 5.7, an overview of the interpersonal elements of the clause is presented. Following this, section 5.8 will discuss the main mood options of the clause, including indicative and imperative mood choices. Finally a summary of the chapter is given in section 5.9 and this is followed by exercises in section 5.10 and further reading in section 5.11.

5.3 The role of Subject and its place in the clause

As mentioned in Chapter 1, one of the main elements of the clause within this strand is that of Subject. It is generally accepted as a well-known term and it is not unique to SFL. In English, the Subject is considered as having a significant role in the clause. Every main clause must have a Subject, whether it is explicitly included or not. In relation to experiential meaning, the Subject most often is expressed by a nominal group that is also expressing a participant, which is usually the first participant. The Subject is also most commonly the first element in a clause, which means it shares the function of Theme in the textual strand of meaning. This was illustrated in Chapter 1 with the example Kev gave me the new Jamie Oliver recipe book for my birthday, where Kev has simultaneously the functions of Subject, Actor and Theme. The role of Subject is significant, as we will see, because it is a kind of hub of meaning in the clause since, in the most common configuration of the clause, the core meaning from all three strands of meaning conflate at this place. It is the single most concentrated source of meaning in the clause.

In SFL, Subject is seen to play a major part in determining the mood of the clause (see section 5.8). Together with the Finite verbal element, the functioning of the Subject guides the interactional nature of the clause. In Text 5.1, we can identify an alternation in the location of the Subject depending on whether the clause is in the form of a question (interrogative mood) or not. I’ve relisted certain clauses from that text in order to concentrate on the Subject. In examples (1) to (5), given below, I have underscored the Subject for each clause since we haven’t yet covered how to recognize the Subject (this will be done in section 5.3.1).

(1) Can you believe that?

(2) Women don’t know the offside rule

(3) They don’t

(4) This isn’t the first time, is it?

(5) Didn’t we have one before?

What we notice is that the Subject is first in the clause most of the time and, when it is not, the clause is in the interrogative mood (in the form of a question, but there is more to say about this later). In these cases, we find an auxiliary verb before the Subject. It is this difference in the Subject location that is a determining factor in both what the Subject is and what the mood structure of the clause is. In this sense, the Subject is the element of the clause that lets the speaker negotiate what he or she wants to do with the clause; for example, is it to tell someone something? Is it to ask someone something? Example (4) is interesting because it seems to be doing both, and indeed it is. The clause itself begins with the Subject and is followed by the verb, which indicates declarative mood; however, at the end a question is added in the form of a tag question where the Subject is ordered after the verb.

In SFL the Subject is seen as having the function of pivoting interaction in the sense that it determines to a large extent what can be said next. As Thompson (2004: 53) explains, the speaker uses the Subject to make a claim about something and the next speaker ‘can then accept, reject, query or qualify the validity’ of this claim. This is illustrated in examples (2) and (3) above, where Mr Gray makes a claim about women not knowing the offside rule in football and Mr Keys accepts the validity of this claim. If, in his response, Mr Keys had changed the Subject of his clause, he would have had to change the proposition and offered a new claim (e.g. men know the offside rule or mendo). As this example shows, the Subject plays a key role in interaction. It is this functional role that distinguishes Subject as a functional element from traditional notions of subject as grammatical constituent.

In the next section, the Subject will be considered from the analyst’s perspective. The main structural units expressing Subject will be discussed and tests for identifying Subject will be presented. More detail about the Subject element and its interaction with the Finite element will be given later in section 5.8, when we consider the Mood element.

5.3.1 Identifying Subject

In the excerpt given in Text 5.1, each Subject was expressed by a nominal group. In fact, this is by far the most frequent structural unit associated to the Subject element. This is not surprising since the unit expressing Subject will most commonly also express a participant and, as was shown in Chapters 3 and 4, the nominal group is the main resource available in English for these functions. Given what we already know about the nominal group and where to expect the Subject, it is relatively easy to find the Subject of the clause. However, as was discussed earlier in this book, clauses can express complex relations through embedding and this can present some challenges when analysing the clause.

There is something inherently nominal about the Subject in English and we can recognize this by the fact that any Subject can be replaced by a pronoun. This may well be a property of association between nominal groups and Subjects or it may simply be the case that, when an embedded clause expresses a Subject function, it is in fact being used to represent a kind of complex entity. For example if we compare apples and eating apples in examples (6) and (7) the Subject in each case can be replaced by a pronoun, although the pronoun is not the same one since clauses function as singular entities in English.

(6) apples are good for you (vs. they are good for you)

(7) eating apples is good for you (vs. it is good for you)

This point about pronoun replacement is important. It is based on the same principles of groups that were discussed in Chapter 3. In other words, whether the Subject is expressed by a nominal group or a clause, it is always expressed by a single structural unit. The pronoun replacement test can therefore be used to help identify the unit which expresses the Subject.

As discussed above, one of the principal functions of the Subject in English is to indicate a distinction between declarative (e.g. women don’t know the offside rule) and interrogative mood (e.g. didn’t we have one before). An understanding of the interaction of the Subject and the auxiliary verb can be used to help work out the boundaries of the unit expressing the Subject. Fawcett (2008) refers to this as the Subject test (see below). This test involves taking a declarative clause and re-expressing it as an interrogative clause. In doing so, the Subject will be revealed since it will be the unit which swaps places with the auxiliary verb.

There are two conditions to using this test: (1) the clause must first be in declarative mood and (2) the clause must include an auxiliary verb. Condition (1) can be met even if the clause under consideration is not in the declarative mood because it can simply be re-expressed in the declarative. Condition (2) is necessary because the interrogative structure in English requires a finite auxiliary verb (e.g. do you eat fish, or can you eat fish) unless the verb is the copular verb be (e.g. are you a fish). In some varieties of English, have can also work this way (e.g. have you a car vs. do you have a car). If the clause under consideration does not include an auxiliary verb then one must be inserted for the purposes of the test and this can either be a support auxiliary (e.g. do), a modal auxiliary (e.g. can) or other auxiliary verbs (e.g. be or have).

The Subject test (adapted from Fawcett, 2008)

1. Check whether the clause under consideration is in the declarative mood.

2. Check whether the clause includes an auxiliary verb.

3. Re-express the clause in the interrogative mood.

4. Identify the Subject based on the boundaries created by the displacement of the Subject.

In order to demonstrate how this test works, examples have been selected from previous chapters to test for the Subject for each clause. These are given below in examples (8) to (13). The Subject test will be used in each case to identify the Subject.

(8) A mass surveillance proposal for wiretapping every communication crossing the country’s border was introduced in 2005

Subject test:

1. Is the clause in the declarative mood? Yes.

2. Is there an auxiliary verb present? Yes.

3. Re-express the clause as an interrogative:

Was | a mass surveillance proposal for wiretapping every communication crossing the country’s border | introduced in 2005?

4. The Subject is identified as: a mass surveillance proposal for wiretapping every communication crossing the country’s border.

(9) The leather bag that I saw in Marks and Spencer is expensive

Subject test:

1. Is the clause in the declarative mood? Yes.

2. Is there an auxiliary verb present? No, but the verb is be.

3. Re-express the clause as an interrogative:

Is | the leather bag that I saw in Marks and Spencer | expensive?

4. The Subject is identified as: the leather bag that I saw in Marks and Spencer.

(10) Seat belts must be worn at all times when seated

Subject test:

1. Is the clause in the declarative mood? Yes.

2. Is there an auxiliary verb present? Yes.

3. Re-express the clause as an interrogative:

Must | seat belts | be worn at all times when seated?

4. The Subject is identified as: seat belts.

(11) For this study, six target groups of passengers were considered

Subject test:

1. Is the clause in the declarative mood? Yes.

2. Is there an auxiliary verb present? Yes.

3. Re-express the clause as an interrogative:

For this study, were | six target groups of passengers | considered?

4. The Subject is identified as: six target groups of passengers.

(12) Pull the rubber strap behind your head

Subject test:

1. Is the clause in the declarative mood? No. Re-express as declarative: you pull the rubber strap behind your head.

2. Is there an auxiliary verb present? No. Add an appropriate auxiliary verb: you should pull the rubber strap behind your head.

3. Re-express the clause as an interrogative:

Should | you | pull the rubber strap behind your head?

4. The Subject is identified as: you.

(13) Can you believe that?

Subject test:

1. Is the clause in the declarative mood? No. It needs to be re-expressed as a declarative: you can believe that.

2. Is there an auxiliary verb present? Yes.

3. Re-express the clause as an interrogative:

Can | you | believe that?

4. The Subject is identified as: you.

In addition to the pronoun replacement test and the Subject test, there is one additional approach to identifying the Subject of a clause in English. This involves the use of tag questions, such as in example (14) below (originally example (4) as given above). Tag questions attach to declarative clauses and they consist of two parts; a pronoun reference to the Subject and an auxiliary verb, in the same order as in the case of interrogative clauses. In addition to this particular structure, tag questions often reverse the polarity of the clause such that a declarative clause which expresses a negation as in example (14) will usually have a positive tag question.

(14) This isn’t the first time, is it?

In this example, the tag question, is it, is roughly equivalent to an interrogative expression of this clause (i.e. is it the first time? or isn’t it the first time?). As concerns the identification of the Subject, the most relevant part of these tag questions is the repetition of the Subject of the clause in the form of a pronoun. This property of the tag question can be exploited as a device for identifying the Subject of a clause since in theory any declarative clause can have a tag question attached to it. As with the structure of interrogative clauses, tag clauses require an auxiliary verb except for the copular be, which, as shown in example (14), does not require the addition of a supporting auxiliary verb. Basically, then, if we want to identify the Subject of a clause, it should reveal itself when a tag question is added to the clause. As with the Subject test, for this test to work, the clause must first be expressed as a declarative clause.

The Tag Question test

1. Ensure the clause under consideration is expressed as a declarative. If it is not, then re-express the clause such that it is.

2. If the clause includes one or more auxiliary verbs, use the first one to form the tag question.

3. Complete the tag question by adding an appropriate pronoun following the auxiliary verb.

4. Identify the Subject by resolving the pronoun reference.

As for the Subject test, examples from earlier chapters will be used to show how the test can be used to identify the Subject of each clause.

(15) It was delivered very quickly and in good order

Tag question test:

1. Is the clause under consideration expressed as a declarative? Yes.

2. Does the clause include one or more auxiliary verbs? Yes.

3. Tag question: It was delivered very quickly and in good order, wasn’t it?

4. The Subject is: it.

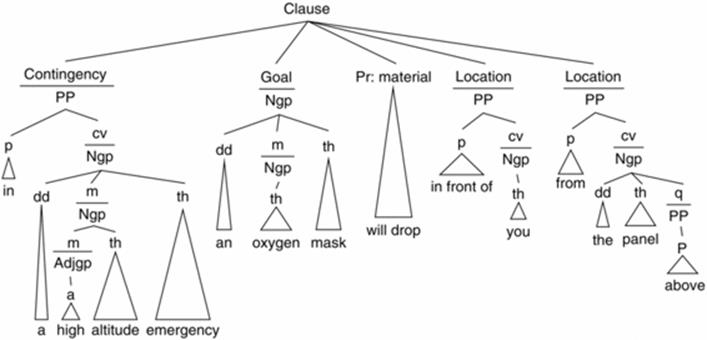

(16) In a high altitude emergency, an oxygen mask will drop in front of you from the panel above

Tag question test:

1. Is the clause under consideration expressed as a declarative? Yes.

2. Does the clause include one or more auxiliary verbs? Yes.

3. Tag question: In a high altitude emergency, an oxygen mask will drop in front of you from the panel above, won’t it?

4. The Subject is: an oxygen mask.

(17) After you are wearing it securely, a tug on the hose will start the oxygen flow

Tag question test:

1. Is the clause under consideration expressed as a declarative? Yes.

2. Does the clause include one or more auxiliary verbs? Yes.

3. Tag question: After you are wearing it securely, a tug on the hose will start the oxygen flow, won’t it?

4. The Subject is: a tug on the hose.

This section has presented a foundation in understanding the Subject element, including various criteria for identifying it. In addition to the Subject, the Finite is also a key element in the interpersonal strand of meaning. The next section provides a detailed discussion of the Finite element and how to recognize finite clauses.

5.4 The Finite element

In the previous section, the focus was on the Subject specifically but it should be clear that it is very difficult to talk about the Subject without discussing its interaction with certain verbal items. This interaction is illustrated very nicely in the ‘Argument Sketch’ by Monty Python. An excerpt from this sketch is given in Text 5.1 below, where in most cases the so-called argument is reduced and carried through the Subject and a particular verbal item.

Text 5.2 Excerpt from Monty Python’s ‘Argument Sketch’

MICHAEL PALIN: Is this the right room for an argument?

JOHN CLEESE: I’ve told you once.

MP: No you haven’t.

JC: Yes I have.

MP: When?

JC: Just now!

MP: No you didn’t.

JC: Yes I did!

MP: Didn’t.

JC: Did.

MP: Didn’t.

JC: I’m telling you I did!

MP: You did not!

JC: I’m sorry, is this a five-minute argument, or the full half hour?

MP: Oh. . . Just a five-minute one.

As this example shows, the most significant elements governing the interactional and interpersonal elements of the clause concern the Subject and what are called finite verbal operators, as for example in the following instances taken from the excerpt:

I have ![]() you haven’t; I did

you haven’t; I did ![]() (you) didn’t; is this. . .

(you) didn’t; is this. . . ![]() (it is). . .

(it is). . .

We find here the means of assertion and contradiction are expressed through the Subject and certain auxiliary verbs. This is also true for the expression of the interrogative mood, although the order of the two elements is inverted, as was discussed in the previous section. The functional relationship between these two elements will be discussed below in section 5.8 when clause mood is presented. In this section, the focus will be on the finite verbal operators.

In English, each finite clause contains an element that expresses the finiteness of the clause; this is the part of the clause that enables it to be finite. The distinction between finite and non-finite clauses will be addressed in section 5.4.2.1, but for now we will concentrate on the rather abstract notion of finiteness. The difficulty with the concept of finiteness is that it carries grammatical information rather than lexical and this often makes it difficult to identify. Essentially, the Finite element is what gives the clause a point of reference; it provides a bounded limit to the clause and this is something that speakers recognize. The most common way that this is understood is as inflectional tense (i.e. past or present). In this book, the finiteness is defined as a verbal item which expresses tense, modality or mood. This means that it is not only expressed by tense but includes any inflectional or grammatical morphology that restricts or limits the clause. The result of this is that a clause is considered finite if at least one of the following conditions is met:

· The clause includes a Finite verbal element that can be shown as an inflection for past or present tense (e.g. he walks vs. he walked or he is walking or he was walking)

· The clause includes a Finite verbal element in the form of a modal auxiliary verb (e.g. can or should, as in I can swim).

· The clause includes a verbal operator that can be shown to be inflected for grammatical mood (e.g. indicative mood vs. imperative mood, as in you are happy vs. be happy).

If none of these conditions are met then the clause is non-finite.

5.4.1 Primary and modal auxiliary verbs

While all lexical verbs have the potential to be inflected for tense (e.g. talks/talked; eat/ate; run/ran), there is traditionally a distinction made between the different types of auxiliary verbs. In this book, a very basic distinction will be made between modal auxiliary verbs and what we will call primary auxiliary verbs. In terms of the interpersonal metafunction there are really only two key issues concerning auxiliary verbs. The first concerns the need in English for a Finite element to express mood (as we will see further in the chapter), which is expressed by the first verbal item in a finite clause and might involve an auxiliary verb but not necessarily so. The second involves the speaker’s intrusion on what is being said, and one of the main ways of doing this is through the expression of modality. Modal auxiliary verbs have a double function: they express the Finite element of the clause and they express the speaker’s modality. Therefore, the basis for the two categories of auxiliary is really a shortcut to facilitate discussion of auxiliaries such that it is convenient to talk about modal verbs on the one hand and all other types of auxiliary verbs (primary) on the other hand.

As was shown in Chapter 2, auxiliary verbs have various roles to play in the clause. In English, temporal, aspectual and modal meaning is often built up by a kind of string of verbs, beginning with the Finite verbal element and ending with the lexical verb (e.g. I might have been being tricked by that guy, from Chapter 2).

Before moving on to consider non-finite verbs and clauses, it may be useful to be clear on the use of the term ‘tense’ in this discussion. Tense refers to grammatical meaning which can be evidenced through inflectional morphology; it concerns the structural form of a verb. However, this is quite different from the functional representation of time from the speaker’s perspective. For example, there is no future tense in English. What this means is that there is no inflectional morphology in English to indicate future reference, as there is in some languages such as French. This does not imply that speakers cannot refer to future times in English – they certainly can – but it is done through the use of auxiliary verbs. Most commonly will (e.g. I will call you tomorrow) is used to refer to a future time-reference point but it is quite common to use the present tense (e.g. I’m eating lunch at work tomorrow). Consequently, the temporal reference a speaker makes is not always directly related to the grammatical tense of the verb form.

There is also one other important point to make concerning tense. As stated above, tense is used in its grammatical or inflectional sense and it does not relate directly to the speaker’s time reference. English tends towards the use of verb complexes to express time reference and this usually involves a combination of what is generally accepted as tense and aspect. Whereas tense can be identified inflectionally, aspect is much more difficult to define since this kind of meaning has not been grammaticalized in English. What is commonly referred to as aspect in many approaches to grammar is expressed through combinations of verbs in English (e.g. progressive forms such as has been reading). The important thing about tense and aspect is that both relate to time reference for a given situation. In SFL, primary tense is used as a term which includes grammatical (inflectional) tense, and secondary tense is used to refer to the time reference achieved through verbal combinations (e.g. he has been working). Aspect in SFL is reserved for distinguishing non-finite clauses; in other words, perfective (infinitive forms, e.g. to work) and imperfective forms (participle forms, e.g. eaten), as we will see in the next section.

In summary, then, there are two main classes of auxiliary verb. One that expresses modality and another that expresses primary and secondary tense. These two classes are not necessarily mutually exclusive, as it is possible for an auxiliary verb to express meaning from both as in the case of lexical items such as have to, which express both modality and tense.

5.4.2 Finite and non-finite clauses

Clauses can be either finite or non-finite. Given the discussion above about finiteness, clauses which are limited by tense, modality or mood are finite. Non-finite clauses, by definition, have no Finite element and therefore they are not limited in these ways. In example (7), shown above, the subject is expressed by an embedded clause, eating apples. There is no identifiable Finite element that limits this clause in any way. The main or matrix clause, eating apples is good for you, clearly is finite because we can contrast the tense or modality: eating apples was good for you vs. eating apples might be good for you. However, this is not possible with the embedded clause eating apples; there is no tense, no modality and no mood within this clause. Perhaps equally significant is the absence of a Subject (although this can often be inferred or recovered by the surrounding context). What this suggests is that non-finite clauses have the capacity to represent a situation in far more abstract terms.

Traditionally, finite status is attributed to the clause as a whole and we tend to talk about finite clauses and non-finite clauses. Because this status is usually identified grammatically by inflectional verbal morphology or by modal auxiliary verbs, there is a strong association between verbs and the Finite element. As will be discussed below in section 5.7, the Finite element is included as part of the verb group, although some would argue that it really is an element of the clause and not the verb group. The remainder of this section presents non-finite clauses in English, including re-expression tests for recognizing finiteness.

5.4.2.1 Three types of non-finite clauses

In English, there are three types of non-finite clauses, and each type is based on the morphological structure of the first verb in the clause: perfective (e.g. ‘-en’ or ‘-ed’ forms); progressive (e.g. ‘-ing’ forms); and infinitival (e.g. ‘to + verb’ forms). Each type is presented below using examples from the British National Corpus (BNC).

1. Perfective non-finite clauses

In finite clauses, the past participle verb form is always preceded by the perfective auxiliary have in the active voice and by the passive auxiliary be in the passive voice. In perfective non-finite clauses, we find the past participle verb form in the first verbal position without any preceding auxiliary verb which would predict its occurrence. Examples of this type of non-finite clause are given in examples (18) and (19). Although these examples show the non-finite clause in initial position, they are not restricted to this position in the clause.

(18) Crushed by eight strokes over 18 holes the following day, it was Norman’s turn to produce a white towel

(19) Convinced that it was genuine, they decided to find local hosts

2. Progressive non-finite clauses

Progressive (i.e. ‘-ing’) verb forms are always preceded by the progressive auxiliary be in finite clauses. In a similar pattern to perfective non-finite clauses, progressive non-finite clauses include the progressive verb form without the progressive auxiliary verb. This type of non-finite clause is illustrated in examples (20) to (22).

(20) Getting married and having a child is better than having a child and getting married

(21) Having left Tony and his Mum at his appointment, I set off in the direction of the A4

(22) Maybe seeing their mother and father in such pain was having a bad effect on the little girls?

3. Infinitival non-finite clauses

This type of clause explicitly marks the fact that it is not finite (i.e. infinite). The verb is in its uninflected form, unlike with the two previous types, and it includes the particle to, which marks the infinitival form. The inverse of this is not true since the absence of the particle does not mean that the verb is not in an infinite form; there are many instances where the infinitival verb form does not require the to particle (e.g. in imperative clauses such as be happy! or eat your dinner! or following modal auxiliaries as in he might be happy or the doctor should see you soon). The difficulty in recognizing this is often due to the fact that English has lost most of its verbal inflectional morphology and most regular verbs appear in a form that looks just like the infinitival form (compare: I talk, you talk, he talks vs. I am, you are, she is). Like the previous two types of non-finite clause, the occurrence of this verb form is not triggered by any preceding auxiliary verb and there is no Finite element identifiable that would account for the infinitival form. Consequently the clause is non-finite. Infinitival non-finite clauses are shown in examples (23) to (26).

(23) To win the strike on their terms, the unionists would have to shut down not only the union mines, but also the non-union ones

(24) To survive is to dig into the pit of your own resources over and over again

(25) Educating young people to drink responsibly and in moderation is best achieved by parents setting a good example

(26) Information to be contained in personal data shall be obtained, and personal data shall be processed, fairly and lawfully

The examples given above will hopefully illustrate that non-finite clauses are included within clauses in various ways and in various positions. In each case, the non-finite clause is embedded in the situation for some particular use. This may be to express the Subject of the clause (as in examples (20), (22), (24) and (25)) or it may be to express a circumstance (as in examples (18), (19), (21), (23)). There are many functions that these embedded clauses may serve. In Chapter 3, for example, we saw how the qualifier element may be expressed by an embedded clause; we can now expand on this and include both finite and non-finite clauses. Even earlier in Chapter 2, the complexity of the English clause was introduced by the ‘House that Jack Built’ example, where the amount of embedded clauses is humorous. Recognizing these clauses is a key part of analysing English grammar, and the next section offers some guidance in doing this.

5.4.2.2 Recognizing non-finite clauses

The descriptions given above for non-finite clauses can be used to help identify these clauses. Each type relies on the patterns of the ways in which verbs can combine in English to form certain types of interpersonal meaning such as tense (especially secondary tense), modality and mood. However, the non-finite clauses are recognizable by the absence of key features of interpersonal meaning: notably no Finite element and in many cases no explicit Subject.

There are therefore certain characteristics that can be identified and tested in determining the finite status of a clause. Three characteristics will be used to determine the finite status of a clause:

1. Finiteness: Finiteness can be identified. As discussed above, if a clause is finite then the Finite element must be identifiable and can be revealed by re-expressing the clause. It will be impossible to do this with non-finite clauses since they do not display any tense, modality or mood.

2. Auxiliary morphology: Non-finite clauses display unexpected verb forms since they appear in what is a recognizable form (progressive, perfective or infinitive) but without a finite precedent trigger (e.g. specific auxiliary forms).

3. Pronoun replacement: All embedded non-finite clauses fill a particular function in a higher unit within the clause (e.g. participant, circumstance or qualifier). Therefore in most cases a pronoun should normally be able to replace this unit in expressing the function. It is important to note that this will not be a reliable measure in all instances (e.g. for qualifiers) but it will nevertheless be a useful complementary test.

In order to illustrate how this works, example (22) will be used to determine the finite status of the embedded clauses. However, before the test is begun, the clause must be approached following the steps that have already been identified. First the process must be identified, and this way each verb in the clause is identified. If we find more than one, we need to determine which one is expressing the process.

Maybe seeing their mother and father in such pain was having a bad effect on the little girls?

The verbs have been underlined in the example. There are three verbs but only one will express the process and it must be expressed in a finite clause. Therefore, it is important that we consider the finite status of these verbs.

1. Finiteness. This characteristic should be identifiable in a finite clause. The verbs need to be tested for expressions of tense, modality or mood.

o seeing: there is no tense expressed with this verb and it is therefore not limited by time reference. No verbal modality can be added and there is no expression of mood.

o was having: was is the past tense of the verb be, and consequently was having must be finite and there is no need to consider finiteness any further. However, we could also test for modality to see if a modal verb is possible: seeing their mother and father in such pain may have been having a bad effect on the little girls.

o Result: ‘seeing’ is non-finite; ‘was having’ is finite.

2. Auxiliary morphology. Two of the verbs occur in the progressive form but only one of them, having, has a progressive auxiliary preceding it. Based on the verbal morphology, having is accounted for by the presence of a preceding finite auxiliary and seeing is not. Therefore, we conclude that seeing is non-finite and having is finite.

3. Pronoun replacement: The test presumes that there is an embedded clause. In this example, the embedded clause has see as its process: seeing their mother and father in such pain was having a bad effect on the little girls; where the nominal group their mother and father is expressing the participant of Phenomenon. If this is functioning as a unit within the clause (i.e. in this case as Subject), a pronoun should be able to replace the entire embedded clause: It was having a bad effect on the little girls.

We could also apply the Subject test at this point to verify the embedded clause as expressing the Subject:

Was seeing their mother and father in such pain having a bad effect on the little girls?

The result of these tests is that the clause given in example (22) includes a non-finite embedded clause (with see as the process), which expresses the function of Subject. This means that the process of the main clause is expressed by have. At this point, we would be able to carry out the rest of the analysis.

The important distinction then between finite and non-finite clauses is the identifiability of a Finite element in the clause. Non-finite clauses, once probed, will not display any evidence of finiteness. Furthermore, they maintain observable structural characteristics that make them relatively easy to identify. Finally, as with other units of the clause, they will serve to express a particular function within the clause.

5.5 Modality

In this chapter, the concept of modality has so far been introduced in terms of the auxiliary verbs and their contribution to mood. In this section, modality as a meaning is considered and this is presented by looking at the types of modality that can generally be expressed by modal verbs and modal adjuncts. As Halliday and Matthiessen (1999: 526) explain, ‘modality is a rich resource for speakers to intrude their own views into the discourse: their assessments of what is likely or typical, their judgments of the rights and wrongs of the situation and of where other people stand in this regard’.

Modality can be a difficult meaning to capture since it is not easily divided into relatively discrete categories. It covers a range of meanings that reflect the speaker’s judgement of what he or she is saying. For example, this range extends from subtle expressions of doubt (e.g. he might arrive today or perhaps I’ll go) to explicit indicators of certainty (e.g. he will arrive today or I will certainly go). Consequently modality is often discussed in terms of degrees (high, median, low), where modality is seen as a continuum.

It is also generally accepted that modality can be expressed on two main axes, or as two main types: epistemic and deontic modality.

Epistemic modality, called modalization in SFL terms, is a kind of connotative meaning relating to the degree of certainty the speaker wants to express about what he or she is saying or the estimation of probability associated to what is being said (e.g. He could take my car or He is probably taking my car).

Deontic modality, called modulation in SFL terms, is also a kind of connotative meaning but, in contrast to epistemic modality, it relates to obligation or permission, including willingness and ability (e.g. He can take my caror He is absolutely taking my car).

As the examples above show, modality is expressed by modal auxiliary verbs (e.g. can, should, must) and by various lexical items (usually adverbs such as probably) or groups which function as modal adjuncts (e.g. by all means).

Modal verbs are easy to identify as there are nine of them:

can, could, shall, should, will, would, may, might, must

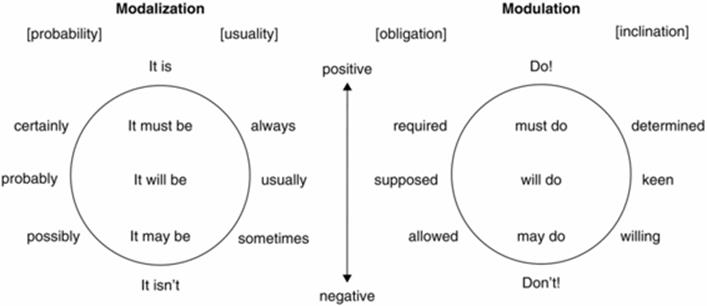

Modal adjuncts are a much more open class. Although the most frequent lexical representation is using certain adverbs, it also includes fused (or fossilized) forms such as historical verb compounds (e.g. maybe) or formulaic expressions such as by all means. Figure 5.1 illustrates the relationships amongst the main types of modality (modalization and modulation), and polarity and mood. It also includes a view of modality as continuum or range between positive and negative. As this diagram shows, it can be difficult to associate specific lexical items (especially modal verbs) with a particular type of modality since there is considerable overlap in use. The surrounding context becomes very important in determining the intended meaning of the speaker.

Figure 5.1 Relation of modality to polarity and mood

(Halliday and Matthiessen, 2004: 619)

5.6 Polarity

Polarity refers to the positive or negative value assigned to the clause by the speaker. It is often presented along with the Finite element but, since it is a kind of meaning that can be expressed in both finite and non-finite clauses, it properly deserves a section of its own. It relates most directly to the interpersonal metafunction because of the influence of the speaker in using polarity to interact with others. This section will briefly present polarity and the role it has in finite and non-finite clauses and how it relates to modality.

Polarity captures a dichotomy of the clause in terms of positive and negative polarity. All clauses can be identified as having positive or negative polarity. Positive polarity is the unmarked polarity as there is no marker of positive polarity in English. Negative polarity is always marked and it is expressed by the morpheme not (whether by the free morpheme not or the bound variation of this morpheme, ‘-n’t’, as in he didn’t go or he did not go).

This seems rather straightforward and it frequently is. In finite clauses, there is a gravity between the Finite element of the clause and the polarity marker which results in a fusion or conflation of the negator element and the Finite element (e.g. can’t, didn’t, haven’t, isn’t). In non-finite clauses, the absence of a Finite element means that only the stressed form of not can be used since there is no finite item with which to conflate the negative marker: Maybe not seeing their mother and father in such pain was having a bad effect on the little girls.

However, negative polarity can be complex in certain cases. For example, polarity is sometimes transferred to the main clause from an embedded or subordinate clause (e.g. he doesn’t think she is coming vs. he thinks she isn’tcoming). It can also be difficult to analyse polarity in cases where the negation is aligned with a non-verbal item in the clause. For example, if we compare the following pair of clauses, She doesn’t have a brother/any brothers vs. She has no brothers, the negation in the first instance uses a polarity marker but in the second instance the negation occurs within the nominal group as a determiner. Finally sometimes the negation is expressed through modality rather than polarity, as shown in the following two examples: he doesn’t come here vs. he never comes here. In the second instance, negation is expressed by a modal adjunct and technically the clause expresses positive polarity.

5.7 An interpersonal view of the clause

So far, this chapter has concentrated on specific concepts that contribute to interpersonal meaning. This section presents the view of the interpersonal metafunction from the perspective of the clause. Two elements are seen as primary or central to interpersonal meaning. These are the Subject and Finite elements. This is not to say that the other elements described above are not important but rather that these two elements combine to determine the mood of the clause, which will be discussed in more detail in section 5.8. In this section, a functional–structural description of the clause with respect to the interpersonal metafunction will be given, as was done for the experiential metafunction in Chapter 4.

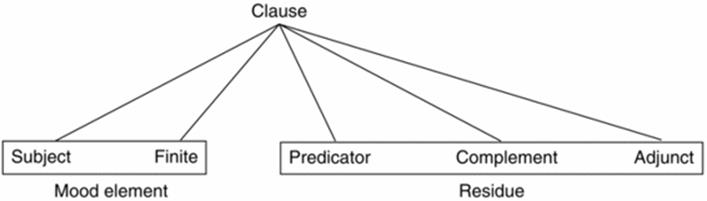

We have already seen how the Subject and Finite elements interact to negotiate meaning in terms of asking questions or making statements. Because of this special relationship in English between the Subject and the Finite element, they are seen as constituting the Mood element of the clause. This is the element that determines the mood choice of the clause (e.g. declarative, interrogative or imperative). The remainder of the clause is referred to as the Residue element of the clause but it does not directly contribute, as an element, to the expression of interpersonal meaning in the same way as the Mood element does. In addition to Subject and Finite, there are other interpersonal elements in the clause: Predicator, Complement and various types of adjunct. Each of these will be explained in the next section, where we will consider how interpersonal meaning maps onto experiential meaning.

5.7.1 Experiential and interpersonal structure

The view of the clause from the interpersonal metafunction is considerably different from what we saw in our presentation of the experiential metafunction. With experiential meaning, the clause is seen as representing experience through processes, participants and circumstances. With the exception of Subject and Finite, interpersonal meaning is less concentrated on particular units than is the case in experiential meaning, and we find interpersonal meaning spread throughout the clause in various ways. This can be, for example, in the use of modal adjuncts, modal finites, or certain lexical items which indicate the speaker’s evaluation (e.g. man vs. idiot). The main distinction made is between mood and modality. As in the experiential metafunction, the functional elements must be expressed in some form but the challenge is that the relationship between function and structure is not as direct as in experiential meaning.

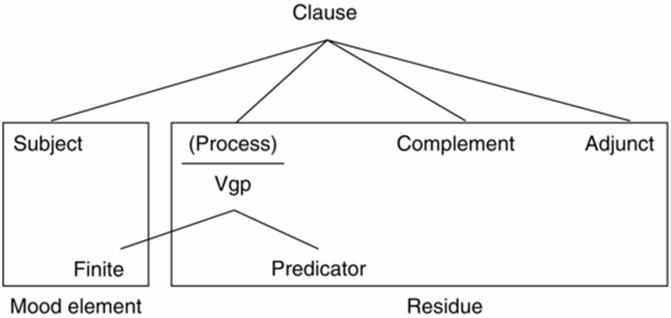

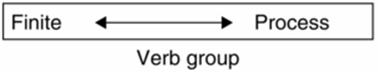

A single-strand view of the clause for interpersonal meaning could be presented as shown in Figure 5.2, where Subject and Finite, as the two most significant elements of the clause interpersonally, are given on the same level. This is not a convenient representation for analysing the clause because the Finite is never a free morpheme; in other words, it is bound to some verbal item. Consequently, it could become quite cumbersome to isolate the Finite element from the rest of the verb group and there would be no analytical advantage to this.

Figure 5.2 Single-strand view of the interpersonal clause

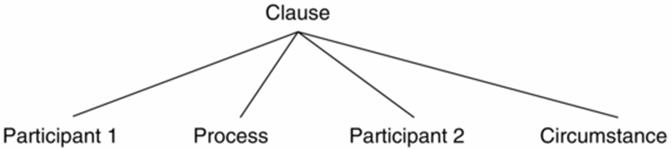

If we take a multifunctional approach, like the position taken in this book, the representation of the multiple functions should, ideally, map onto each other where the same unit expresses more than one function. As a reminder of the basic configuration of the clause in the experiential metafunction, Figure 5.3 illustrates the generic functional elements that express experiential meaning. If we compare this with Figure 5.2 and Figure 5.4, it should be easier to see how the two strands of meaning could map onto each other both functionally and structurally if the representation in Figure 5.4 is adopted. This is certainly not the only way in which these meanings can be represented and we will refine this representation after the next section, where the verb group will be presented in detail.

Figure 5.3 Basic generalized view of the experiential clause

Figure 5.4 Basic view of the interpersonal clause

Based on Figures 5.3 and 5.4, it may already be clear that there is the potential for a direct mapping of experiential and interpersonal meaning for most of the functional elements of the clause as seen so far. For example, Subject will often map onto the first participant (although not always, as in the case of certain process types). The Complement element is the functional label for what are known as objects (direct and indirect objects) in traditional grammar. Any participants which are not functioning as Subject will be conflated with Complement. Circumstance elements conflate with an adjunct element. As there are several types of adjunct, those with a circumstance function are often referred to as a circumstantial adjunct to distinguish them from modal adjuncts. There will be some adjuncts (such as modal adjuncts) which do not have any experiential meaning and therefore they do not express more than one function.

The real challenge is how to reconcile the expression of the process and the Finite. This problem will be considered in the next section, where the verb group is presented. This is the last major structural unit that needs to be covered in order to complete our structural presentation of the clause.

5.7.2 The verb group

The verb group works differently from the other groups described so far. Like other groups, it is centred on a verb but the group itself does not seem to lend itself so easily to the modification of this item as is the case for other groups. Each verb group must have a lexical verb but, given that there are finite and non-finite clauses, it is not a requirement for each verb group to have a Finite element. Most other groups have one pivotal element (e.g. a noun or an adjective) and the other members of the group tend to be expressed by different structural units. The verb group is almost exclusively composed of verbs. This is a feature of how certain types of meaning (e.g. modality, tense) are expressed in English: combinations of auxiliary verbs together with a lexical verb. For every verb group, there will be one pivotal verbal element and the potential for supporting verbal elements.

When considered from a solely structural perspective, the verb group is not really problematic, although of course there are points of debate. The difficulty arises when a multifunctional perspective is taken since it forces us to try to reconcile how each kind of meaning is expressed. If we consider the experiential metafunction, it may simply be that the entire verb group expresses the process, but as we have seen when applying the process test in earlier chapters it is the pivotal verbal element (i.e. the main lexical verb) which primarily determines the meaning of the process. This is not to say that the remaining verbal elements do not contribute to experiential meaning but rather that one element is identifiably more significant than any others from this view, and this element is found towards the right-most end of the verb group, as we shall see in a moment. However, when the verb group is considered in terms of its expression of interpersonal meaning, the main lexical verb is far less significant and, as explained above, it is the Finite element that plays the most important role. In many cases these two functional elements are expressed by a single word (e.g. he ateFinite/process the whole pie). When this is not the case (e.g. he didn’tFinite eatprocess the whole pie), the Finite is necessarily separated from the main lexical verb and the interpersonal focus of attention moves to the left-most element of the verb group. The result is a span across the verb group where interpersonal meaning peaks on the left-most item and experiential meaning peaks on the right-most item, as shown in Figure 5.5. This isn’t very different from the view taken in Chapter 3, where the nominal group was presented as the major grammatical resource for expressing participant functions and, as is being shown in this chapter, also Subject and Complement functions. The verb group is a grammatical resource which expresses complex and multiple functions simultaneously. The difficulty for us is trying to capture this with our limited diagrams.

Figure 5.5 Span of meaning in the verb group

Children pick up on the complexities of what verbs can do from a very early age. When my youngest son was two years and one month old, he wanted to tell me that his father had gone to get his ball. What he actually said is given in example (27).

(27) Daddy’s go getting my ball

We can tell from this that he has some awareness of putting words together to express an action. Clearly we can’t be certain about what precisely he is processing but it does seem reasonable to assume that this utterance shows he has grasped the use of some kind of progressive auxiliary and the ‘-ing’ morphology. There isn’t necessarily evidence that he hasn’t done this right, although we would expect adult speakers to produce either Daddy is getting my ball or Daddy is going to get my ball. This very young speaker may well have a verb in his lexicon that is go get; perhaps due to hearing a high frequency of utterances such as go get your ball, go get your book, and so forth. With this view then, he has perfectly mastered what seems to be a complex verbal expression of the process. The point here is not to discuss child language acquisition but rather to bring to our attention the complexities of expressing the Finite element (interpersonal meaning) and the process element (experiential meaning).

5.7.2.1 The structure of the verb group

The structure of the verb group is complex for a variety of reasons: the way in which the Finite element works in English; the way verbs combine to express complex (secondary) tenses; and the way words combine to form complex verbal lexical items (e.g. to make up). For the reasons discussed above, the Finite and main verbal elements are seen to combine, sometimes with other verbal elements intervening, in the form of a structural unit called the verb group. We can also use a replacement test similar to the pronoun replacement test to show this by replacing even very complex verb groups by a single verb. In all cases, this will be a simple form of the main verb: he might have been drinking tea ![]() he drank tea).

he drank tea).

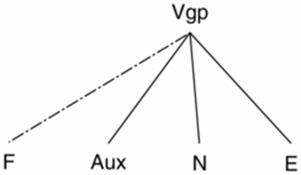

The question of headedness or the pivotal element of the verb group could be seen as depending on the perspective taken: if considered within the interpersonal metafunction, it would have to be the Finite element (F) and if considered within the experiential metafunction it would be the event element (E), which is expressed by the main lexical verb in the verb group (see below). For all finite clauses, the verb group must have both elements, and as already stated both functions can be expressed by a single verb. This may lead to questions as to whether this unit is a group or a phrase but, since not all clauses are finite, not all verb groups require a Finite element. However, all verb groups do require the expression of an event element; in other words, a lexical verb. Therefore, it is simpler to consider that the verb group has one pivotal element (i.e. the event element, E) where the remainder of the verb group serves to expand on this.

The basic structure of the verb group is given in Figure 5.6. In this illustration, the Finite element, F, is indicated by a dashed line since it is an element which cannot be expressed in isolation from other elements; in other words, it must be conflated with at least one other functional element. It always conflates with the first verbal item but this could be one of the various types of auxiliary elements, Aux, or the event element, E. The only remaining element in Figure 5.6 is the negator element, N, which is the element that expresses negative polarity. Halliday refers to this element as the polarity element, but since positive polarity is not marked and only negative polarity is an option this element will be referred to here as negator, a term adopted from Fawcett (2000c).

Figure 5.6 A basic view of the verb group

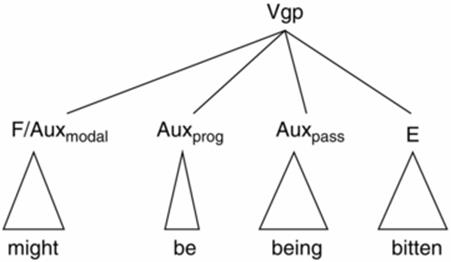

Although the Auxiliary element, Aux, is optional, there may be more than one type expressed: for example, a modal auxiliary + progressive auxiliary + passive auxiliary, as in he might be being bitten by a mosquito. The verb group in this example would be represented as shown in Figure 5.7. Identifying the meaning type is not necessary in all cases; it depends on whether or not the analysis calls for this type of detail. What is important is that the function of the auxiliary element is identifiable.

Figure 5.7 Sample verb group for might be being bitten

One final comment should be made concerning the representation of the functional elements of interpersonal meaning in diagrams. As discussed above, mapping the various functions onto the same unit of structure is challenging to show in a diagram. When representing the clause with a tree diagram, the verb group is a convenient way to clearly identify the Finite element and the remaining elements of the verb group. However, the remaining elements of the verb group constitute the Predicator but it would be quite difficult to label all remaining elements additionally as Predicator. The solution proposed here is that tree diagrams should include all elements of the verb group but that box diagrams only need identify the Finite element, and the remainder of the verb group can then be labelled Predicator. Here is an example of this; in fact this is the most common method of labelling the verb group within systemic functional linguistics:

|

might |

be |

being |

bitten |

|

Finite |

Predicator |

||

5.7.3 Interpersonal analysis of the clause

At this point, the description of the clause from the perspective of the interpersonal metafunction is nearly complete. Mood, as a property of the clause, will be discussed in the next section. However, the functional–structural description of the interpersonal clause has been completed, and in this section some worked examples will be presented in order to show how the interpersonal meanings map onto our description of the clause so far. First, selected examples from Chapter 3 will be reconsidered here by adding the interpersonal functions to the existing description. In addition to this, clauses [1] and [2] taken from Text 5.1 above will be analysed for both experiential and interpersonal meaning in order to show how the analysis is done from the beginning.

In analysing each of these clauses, the steps in the guidelines which were developed in the previous chapter will be expanded to include the content that has been covered in this chapter. New steps have been added related to identifying the Finite and Subject elements and all other interpersonal elements of the clause (mood, modality and polarity). With the additional steps for the elements of interpersonal meaning, there are now nine steps in the guidelines for analysing the clause. These are listed below. The guidelines will be revised again in Chapter 6 after the presentation of textual meaning.

5.7.3.1 Guidelines for analysing experiential and interpersonal meaning

Identify the process

This step involves identifying the main verb (event) of the clause as it will also express the process (see Chapter 4) and in order to do this you will have to identify the Finite element as well, using the criteria given above. It may also be necessary at this point to identify any embedded clauses if there are any but this might be deferred until step 3 in some cases.

Use the process test to show how many participants are expected by the process (see Chapters 2 and 4)

Use the tests developed in Chapters 3 and 4 to identify the internal boundaries of the clause (different elements of the clause)

This step relates to the analogy of finding the walls and rooms in the house, as was discussed in Chapter 2. Here the intermediate structural units of the clause are verified (e.g. nominal groups, prepositional phrases).

Determine the process type and participant roles

This step involves working with the probes and tests developed in Chapter 4 in order to determine the type of process expressed and the particular participant roles.

Identify any circumstance roles

This step considers any potential circumstances in the clause. The questions associated to each type, which were listed in Chapter 4, should be used as probes in identifying the function of the circumstance.

Identify the Finite type

The Finite element will have been identified in step 1 above. In this step, the type of Finite is determined (e.g. temporal, modal).

Use the Subject test to identify the Subject

In this step you will apply the Subject test as given above in order to verify the structural unit which is expressing the Subject of the clause.

Identify all modal elements including markers of negative polarity

In this step, modal adjuncts, modal verbs and/or negator are identified.

Draw the tree diagram

The following clauses have been selected from this chapter and Chapter 4 to illustrate the guidelines for analysing both experiential and interpersonal meaning. The first two were analysed in Chapter 4, which means that they are already familiar and it will be easier to see how interpersonal meaning maps on to experiential meaning.

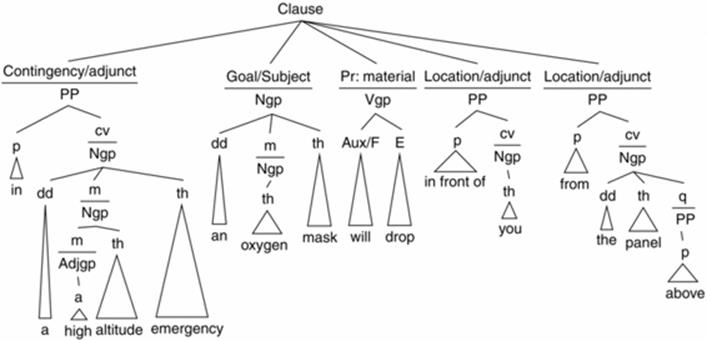

1. [1] In a high altitude emergency, an oxygen mask will drop in front of you from the panel above

2. [2] Place the mask over your mouth and nose

3. [3] Can you believe that?

4. [4] Women don’t know the offside rule

Clause [1] (from Chapter 4 section 4.4.2)

In a high altitude emergency, an oxygen mask will drop in front of you from the panel above

In Chapter 4, this clause was analysed as a material process with one participant, which had the function of Actor. Three circumstances were identified as given in Figure 5.8, which is reproduced here for ease of reference. As is shown by this diagram, the material process is expressed by the verb group will drop. The only candidate for Subject is an oxygen mask, but this will be tested as the steps are followed below. Since steps 1 to 5 inclusive were completed in Chapter 4, the analysis here will begin with step 6.

Figure 5.8 Experiential analysis of the clause In a high altitude emergency, an oxygen mask will drop in front of you from the panel above

Identify the Finite type

There are only two verbs in this clause: the first is will, which is a modal auxiliary verb, and the other is drop, which is a lexical verb. Whenever a modal verb is present in a clause it will always conflate with the Finite element and therefore will expresses the Finite element in this clause.

Use the Subject test to identify the Subject

Following the Subject test, the clause is re-expressed in the interrogative form: In a high altitude emergency, will an oxygen mask drop in front of you from the panel above?

Therefore this shows that an oxygen mask expresses the Subject in this clause.

Identify all modal elements including markers of negative polarity

This clause has one modal verb, will, but no other markers of modality or polarity.

Draw the tree diagram

The interpersonal functions are added to the existing tree diagram, as shown in Figure 5.9.

Figure 5.9 Experiential and interpersonal analysis of the clause In a high altitude emergency, an oxygen mask will drop in front of you from the panel above.

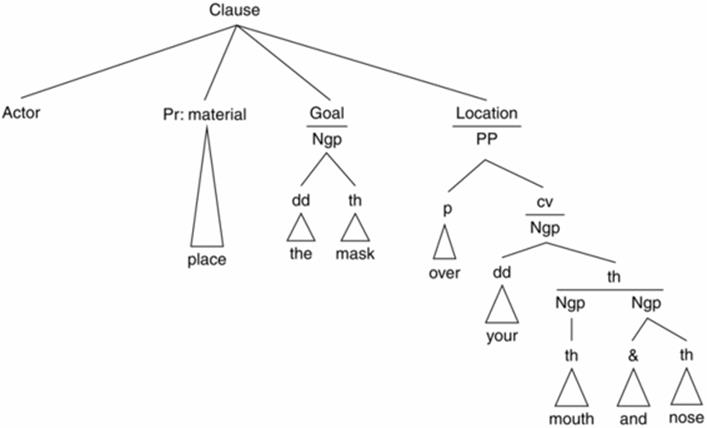

Clause [2] (from chapter 4 section 4.4.2)

Place the mask over your mouth and nose

Like the previous example, this clause has already been analysed up to step 6. The analysis is given here in Figure 5.10, where the clause expresses a material process with Actor (unexpressed) and Goal and one circumstance of Location.

Identify the Finite type

This clause is particularly challenging in terms of recognizing the Finite element. At a glance there is only one verb, place. The problem is that the Finite is not immediately identifiable. There are no auxiliary verbs but we can test for the potential to include an auxiliary verb and we can use the information presented earlier in this chapter to resolve this problem. First, if we refer to Figure 5.1 above, it should be clear that the clause is expressing modulation (obligation) based on the examples given and that therefore the clause is finite. We can also exclude the possibility that the clause is non-finite because it does not match any of the three non-finite clause types for English. If the polarity is reversed, the Finite element will either reveal itself or we will have to reconsider that the clause is non-finite. To do this, we will re-express the clause with negative polarity to see if the negator can conflate with the Finite element: Don’t place the mask over your mouth and nose. Therefore we can conclude that the clause is finite but that the Finite element is not expressed in this instance.

Use the Subject test to identify the Subject

In order to use the Subject test, the clause must be re-expressed with all participants fully expressed. In this case, the Actor was left unspecified but we know from the context that the Actor in this case is the airplane passenger being addressed, i.e. you. This gives: You place the mask over your mouth and nose.

The Subject test requires an auxiliary verb: You can place the mask over your mouth and nose.

Applying the Subject test gives: Can you place the mask over your mouth and nose?

Therefore this shows that you functions as the Subject in this clause, even though it has not been expressed lexically.

Identify all modal elements including markers of negative polarity

This clause expresses modality of obligation.

Draw the tree diagram

The tree diagram showing experiential and interpersonal meaning is given in Figure 5.11.

Figure 5.10 Experiential analysis for the clause Place the mask over your mouth and nose

Figure 5.11 Experiential and interpersonal analysis for the clause Place the mask over your mouth and nose

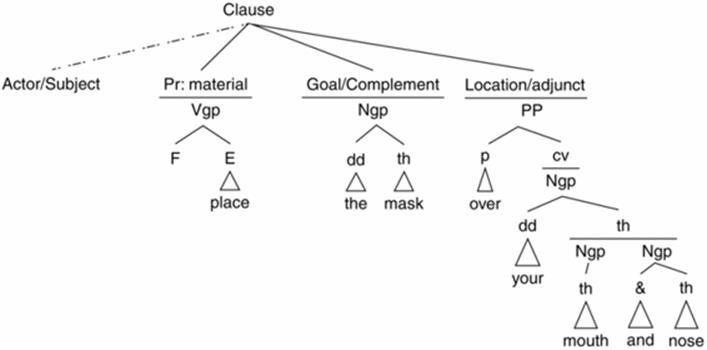

Clause [3] (from Text 5.1)

Can you believe that?

Identify the process

There are only two verbs in this clause: can and believe. The first, can, is immediately recognized as a modal auxiliary verb. Consequently, the presence of a lexical verb is expected, and believe satisfies this. Therefore believe, as the lexical verb, is seen as expressing the process.

Use the process test to show how many participants are expected by the process

Process test: In a process of believing, we expect someone to be believing someone/something. Therefore two participants are expected by this process.

Use the replacement test and/or the movement test to identify the internal boundaries of the clause (different elements of the clause)

Given that the remaining units of the clause are expressed by pronouns, this step is not necessary (i.e. you and that).

Determine the process type and participant roles

Given that the process test determined that two participants were involved, single-participant processes such as behavioural and existential can be eliminated. Verbal processes can be eliminated as well because the meaning of believe in this sense does not involve any meaning related to saying. The clause is also not expressing a relational process since the two participants cannot be related by the verb be. This leaves only material and mental to choose from. As explained in Chapter 4, there is one grammatical way to distinguish between these two process types and this means we can use the present progressive to test for material versus mental processes, since material processes tend to prefer the progressive present. To apply this test, we need to re-express the clause without the modal verb can and compare the clause in the simple present to the present progressive: you believe that vs. *you are believing that.

What we find is that the simple present (i.e. you believe that) is the preferred version and therefore the process is mental. Consequently, the respective Participant roles are Senser (you) and Phenomenon (that).

Identify any circumstance roles

There are no remaining elements of the clause and therefore no circumstances.

Identify the Finite type

The Finite element was identified in step 1 as a modal verb.

Use the Subject test to identify the Subject

Given that this clause begins with an auxiliary verb, we can apply the Subject test in reverse: Can you believe that? ![]() You can believe that.

You can believe that.

This indicates that you is expressing the Subject.

Identify all modal elements including markers of negative polarity

Other than the modal verb already identified for this clause, there are no other markers of modality or polarity.

Draw the tree diagram

The tree diagram is given in Figure 5.12.

Figure 5.12 Experiential and interpersonal analysis of the clause Can you believe that?

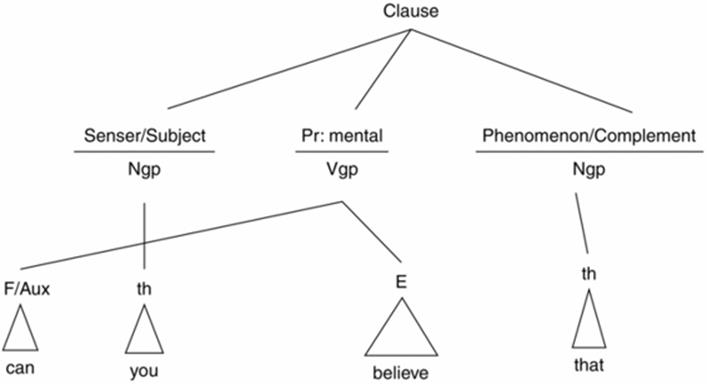

Clause [4] from Text 5.1

Women don’t know the offside rule

Identify the process

There are only two verbs in this clause: don’t and know. The first, don’t, is immediately recognized as a support auxiliary verb (i.e. do) with negative polarity (‘-n’t’). Consequently, the presence of a lexical verb is expected and know satisfies this. Therefore know, as the lexical verb, is seen as expressing the process.

Use the process test to show how many participants are expected by the process

Process test: In a process of knowing, we expect someone to be knowing someone/something. Therefore two participants are expected by this process.

Use the replacement test and/or the movement test to identify the internal boundaries of the clause (different elements of the clause)

We can use the pronoun replacement test to verify the unit boundaries: they don’t know it. This shows that women and the offside rule each constitute single structural units; both are nominal groups.

Determine the process type and participant roles

Given that the process test determined that two participants were involved, single-participant processes such as behavioural and existential can be eliminated. Verbal processes can be eliminated as well because the meaning of know in this sense does not involve any meaning related to saying. The analysis for this clause is the same as for the previous clause, and in order to determine the process type the clauses will be compared in the simple present and the present progressive: women know the offside rule as compared to *women are knowing the offside rule.

What we find is that the simple present (i.e. women know the offside rule) is the preferred version and therefore the process is mental. Consequently, the respective participant roles are Senser (women) and Phenomenon (the offside rule).

Identify any circumstance roles

There are no remaining elements of the clause and therefore no circumstances.

Identify the Finite type

The Finite element was identified in step 1 as a support auxiliary verb (do).

Use the Subject test to identify the Subject

This clause already has an auxiliary verb so we can apply the Subject test directly: Women don’t know the offside rule ![]() Don’t women know the offside rule?

Don’t women know the offside rule?

This indicates that women is expressing the Subject.

Identify all modal elements including markers of negative polarity

There are no markers of modality, but the clause expresses negative polarity through the negator, ‘-n’t’, which is conflated with the Finite element (i.e. don’t).

Draw the tree diagram

The tree diagram is given in Figure 5.13.

Figure 5.13 Experiential and interpersonal analysis for the clause Women don’t know the offside rule

These examples show how the main interpersonal meanings conflate with experiential meaning. Although the experiential meaning in the four clauses analysed is quite similar, the interpersonal meaning has differed in terms of the Subject and Finite elements. These differences are attributed to differences in mood, which is explained in the next section.

Before moving to the discussion of mood, one further aspect of interpersonal meaning should be briefly mentioned. The speaker’s attitude can also be expressed through the selection of lexical items which have an ‘interpersonal element as an inherent part of their meaning, especially those referring to human beings, for example, idiot, fool, devil, dear’ (Halliday and Hasan, 1976: 276). Lexical items can express the speaker’s attitude across a wide range of interpersonal meanings such as familiarity, distance, contempt, sympathy (Halliday and Hasan, 1976). Thompson (2004: 75) refers to this as appraisal, which he defines as ‘the indication of whether the speaker thinks that something (a person, thing, action, event, situation, idea, etc.) is good or bad’. Suggestions for further reading on this topic are given in section 5.11.

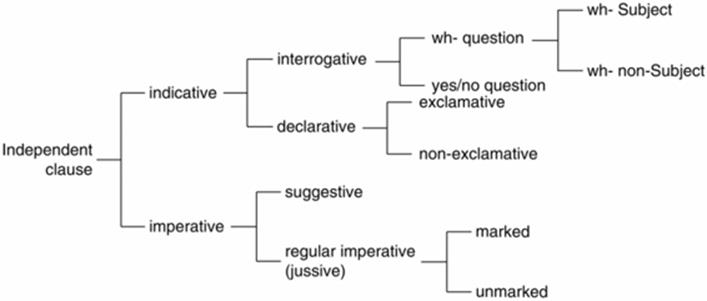

5.8 Mood

This chapter has primarily focused on the identification and expression of specific interpersonal functions within the clause. In this section, we take a look at one of the motivating systems for why the clause functions as it does within the interpersonal strand of meaning. Within the experiential strand of meaning, the speaker can be thought of as a kind of raconteur, someone who recounts experience. Within the interpersonal strand of meaning, the speaker takes on a social role in the speech situation, and in doing so assigns a role to the addressee. According to Halliday (2002: 189), ‘language itself defines the roles which people may take in situations in which they are communicating with one another; and every language incorporates options whereby the speaker can vary his (or her) own communication role, making assertions, asking questions, giving orders, expressing doubts and so on’. Speech functions such as question and order are expressed by the mood system (see Figure 5.14). The differences among the different types of mood choice (e.g. interrogative, declarative or imperative) relate to ‘differences in the communication role adopted by the speaker in his interaction with a listener’ (Halliday, 2002: 189).

Figure 5.14 The mood system

(Thompson, 2004: 58)

The mood system shown in Figure 5.14 (taken from Thompson, 2004: 58) illustrates the range of options potentially available to speakers in terms of the function of the Subject in relation to the Finite, since these two elements combine to define the mood structure of the clause. In other words, the distinction amongst the various mood options is based on the interaction of the Subject and Finite. Interrogative mood and declarative mood are expressed in English by inverting the Subject and Finite (e.g. can you believe that? vs. you can believe that). The non-exclamative declarative clause is what we might call the regular declarative (e.g. he is a nice man) and this is in contrast to exclamative clauses such as what a nice man he is. With exclamative clauses, the verbal morphology is very clearly indicative and the mood structure remains Subject followed by Finite although the Complement (i.e. what a nice man) precedes the Subject. In many cases the Subject and Finite are ellipsed, as in what a nice man.

Within the interrogative system, there are two options. One is what is called wh- interrogative and the other is called polar interrogative. These are sometimes referred to respectively as content interrogatives and yes/no interrogatives. Wh- interrogatives include an interrogative pronoun (see Chapter 2) as in, for example, who ate the cake? what did you eat? where will you go? how can you afford to travel? The use of an interrogative pronoun often indicates content that the speaker expects the addressee to provide. In this sense, the pronoun is used to seek that content. When the ‘sought’ element is the Subject, as in who ate the cake?, then the Subject and Finite do not appear inverted. In these cases, an auxiliary verb is not needed to form the interrogative (so *what ate he? but what did he eat?).

The distinction between indicative and imperative mood is based historically on verbal inflectional morphology. The two mood types were originally distinguished on verbal inflection alone where the imperative mood in the second person singular (you) was expressed by absence of an affix (i.e. null morpheme or null affix), much like Modern English indicative mood (e.g. you walk but he walks) and in the plural, it was expressed by the ‘-(e)th’ (originally ‘-eþ’) affix. This kind of inflectional marker of mood is maintained in many European languages such as German and Welsh. The extensive loss of verbal inflections in Modern English has meant that there is no overt marking on verbs to indicate mood. Consequently, it has to be determined by deduction.

The third person singular (i.e. he, she or it) in the indicative mood is the only remaining source of mood indicators. This information can be used to help determine indicative mood if the clause can be expressed in the third person singular. In the example discussed above, Women don’t know the offside rule, the indicative mood of this clause can be verified by re-expressing the clause in the third person singular without any auxiliary verbs: women know the offside rule ![]() she knows the offside rule. The inflection on the verb is proof of the indicative mood.

she knows the offside rule. The inflection on the verb is proof of the indicative mood.

Recognizing the imperative mood is somewhat more challenging because we have lost the inflectional markers of this mood. Most frequently, neither the Subject nor the Finite is expressed. However, as argued above, imperative clauses are finite and therefore there must be a Finite element which can be recovered. Some would argue that the imperative is marked by a null affix. As concerns the Subject, Halliday (2002: 190) explains that ‘it is present in all clauses of all moods, but its significance can perhaps be seen most clearly in the imperative (because) the speaker is requiring some action on the part of the person addressed’. Clearly, then, imperative clauses have both a Finite and Subject element even though they may not be immediately obvious. This information must be used in order to deduce their presence.