AP English Language & composition exam

PART I

Welcome to the Exam

1

A Brief Introduction to the AP English Language and Composition Exam

WHY DO YOU NEED THIS BOOK?

This book was written for a student whose goal is to achieve the best possible score on the AP English Language and Composition Exam. We at The Princeton Review believe that the best way to achieve this goal is to understand the test—and especially how the test is written. If you understand the limitations that test writers face, you will approach the test in a way that enables you to earn your maximum score—and that’s probably what matters most to you right now. Even if your English Language teacher spends most of the class time discussing her favorite books instead of teaching you about rhetoric, you can still ace the exam with the help of this book. However, if you had excellent English instruction in a course specifically centering on the nuts and bolts of AP English Language, then this book will help you review what you learned and give you valuable test-taking strategies that will ensure your success.

Despite the diversity that might result from differing teachers and curricula, the courses share a common task: to teach you to read and write English at a college level. Likewise, the AP English Language and Composition Exam shares the same goal—it attempts to test you on whether you read and write English at a college level.

HOW IS THIS BOOK ORGANIZED?

In this book, we start by giving you a brief overview of the test—we tell you about the history of the test, what it looks like, how to sign up for it, and what your score means. Then, in Parts II and III, we go through some strategies and techniques for approaching the two parts of the exam: the multiple-choice section and the essay section. The content review portion of the book, Parts IV and V, prompts you to use the techniques you learned in Parts II and III to answer the sample questions and drills you see there. You need to get as much practice using these techniques as you can, and that means using them whenever you have an opportunity.

Got it? Now let’s find out more about the exam itself.

KNOW THE EXAM, AND PRACTICE, PRACTICE, PRACTICE

There’s more to doing well on a standardized test like the AP English Language and Composition Exam than simply knowing all about English. After all, how often have you answered questions incorrectly on a test even though you really knew the material? To do well on the AP English Language and Composition Exam, you need to know not only what will be tested, but also how it will be tested. How many multiple-choice questions are there, and what are they like? This is helpful knowledge to have, if only so you know how to budget your time on test day. What kinds of essays are on the exam, and what do the essay readers expect? If you know what they expect, you can practice giving it to them on practice tests—well before test day.

This knowledge brings us to our next point: It is absolutely essential that you practice before going into “the big game.” Doing some trial runs—answering AP-type multiple-choice questions and writing AP-style essays—is one of the best ways for you to get ready for the AP English Language and Composition Exam. Think about it. If you are a tennis player, you probably practice every day. You practice serving, you practice your backhand, and you play matches against your teammates. This helps you become as prepared as you possibly can for real matches. In the same way, going through drills and taking some full-length practice tests will help you be as prepared as you can be for the AP English Language and Composition Exam.

So what can you do besides faithfully complete the drills and practice tests in this book? Well, there are practice questions and essay questions from past tests on the College Board website, and you can go through those if you feel like you want more practice after you’ve finished this book. Their website is: www.collegeboard.com. You can also get more information by contacting the College Board directly at:

Phone: 609-771-7300 or 877-264-5427 toll-free in the United States and Canada

TTY: 609-882-4118

E-mail: apexams@info.collegeboard.org

A BIT OF HISTORY YOU MAY WANT TO KNOW

Once upon a time, in Ancient Greece, there were scholars who decided that rules for written and oral expression needed to be formalized; among these were Plato and Aristotle. This marked the birth of rhetoric. The Roman rhetoricians continued to develop this important art because they understood the importance of speech in ruling a vast empire.

In Europe, during the Middle Ages, the rules of rhetoric became even stricter. It was determined that to give “proper” form to thought, one had to follow certain rules of expression. By the time the Renaissance rolled around, the goal of expression was to match the models of antiquity. Everyone was striving to live up to the brilliance of the past.

The rest of the story, as it pertains to your AP exam and you, can be summed up in this way: For centuries, writers struggled to liberate themselves from the yoke of formal rhetoric, to invent new forms, and finally to use no forms at all. By the second half of the twentieth century, they had succeeded. Freedom at last! Unfortunately, there was an unanticipated side effect: Reasoned discourse all but disappeared. Horrified professors began to complain that university students were handing in disorganized, illogical drivel. The pendulum began to swing the other way; freshman composition became a mandatory course at most colleges; the formal study of grammar, usage, and rhetoric returned. And high school students, hoping to place out of the freshman composition course in college, began to flock to AP English Language and Composition courses.

AP ENGLISH—DON’T CONFUSE THIS EXAM WITH ITS SISTER

When you sit down to take the AP English Language and Composition test in May, about 374,000 other students will also be sitting down in testing centers around the world to take the same exam. The sister exam to this one (which is often confused with this test) is entitled the AP English Literature exam. It is also given in May, and is taken by about 353,000 students each year. The reason for the existence of these two similar tests is that different freshman college English courses emphasize different things. The Language test assesses knowledge and skills in expository writing or rhetoric, while the Literature test assesses knowledge and skills in dealing with literature, including poetry, which is not tested on the Language test.

The number of students who take the Language exam has grown dramatically over the last five years, while the number of students who take the Literature exam has increased only slightly. If the trend holds, the Language exam will become the more popular one before the end of the decade. The tests are similar in format and are scheduled on different days during the AP weeks, so it is possible to take both exams in the same year. If you are a strong student of both rhetoric and literature, it may be a good idea to take both exams—many students do.

Interestingly enough, almost all of the students who take the Literature and Composition exam take a course that’s specifically designed to prepare them for the test. However, many schools do not have a course that specifically covers AP English Language and Composition. In fact, more students take the AP English Language and Composition Exam without a specific preparatory class than any other AP subject exam. Like the other AP exams, there is no prerequisite for either AP exam in English; anyone who wants to take the tests may do so.

AND DON’T BE SHY…

As you know, AP English courses, like other AP courses, are essentially first-year college courses. Actually, AP English courses are sometimes better than their corresponding courses at college. This is partly because nearly everyone in an AP course is a strong student who wants to be in class; as a general rule, the more excited the class, the more inspired (and interesting) the teacher will be. So, if AP English is available at your school, and if you’re motivated and interested, take it if you have not done so already.

Even if you cannot take the course, if you’re a strong student and you’re just thinking about taking the test, you should do it. Sign up for the AP English Language and Composition Exam, study the material in this book, and go for it! AP English credit enables you to skip ahead of the pack, saves money, looks great on your transcript, and opens up your college schedule so you can get to the really interesting courses faster. Even if you only place out of freshman English (but don’t get any credit for that course), it will have been worth it. If you are wondering what kind of credit is given for AP courses and what score you need to get on the AP to get credit, ask the colleges that you’d like to attend.

SO WHO WRITES THE AP ENGLISH EXAM—AND WHAT DOES IT LOOK LIKE?

The AP English Development Committee writes the test, but ETS (Educational Testing Service) is involved in crafting it too. The AP people (English instructors from high schools and universities) pick the passages and write first drafts of the test questions, but then the ETS people step in and fine-tune the test. ETS’s primary concern is to ensure that the test, especially the multiple-choice section, is similar to previous versions and tests a broad spectrum of student ability.

Luckily for you, ETS has predictable ways of shaping questions and creating the wrong answers. On multiple-choice tests, knowing how the wrong answers are written and how to eliminate them is very important. We’ll discuss this topic in detail in the next chapter, entitled Cracking the Multiple-Choice Questions. So let’s answer the second question in the heading of this section: What will the test look like?

THE FORMAT OF THE AP ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND COMPOSITION EXAM

Below is a helpful outline that describes the basic format for the exam. The total time allotted for the completion of this exam is 3 hours and 15 minutes, or 195 minutes.

Section I: Multiple Choice (60 minutes)—counts for 45 percent of your grade

Total number of questions: 50–55

Section II: Free Response (120 minutes)—counts for 55 percent of your grade

Composed of three essays, which the College Board describes in the following way:

1. Fifteen-minute reading period

2. Analysis of a passage and exposition/presentation of the analysis (40-minute essay on a passage that ETS provides)

3. Argumentative essay (40-minute essay that supports, refutes, or qualifies a statement provided by ETS)

4. Synthesis essay (40-minute essay that integrates information from a variety of sources that ETS provides)

WHAT YOUR FINAL SCORE WILL MEAN

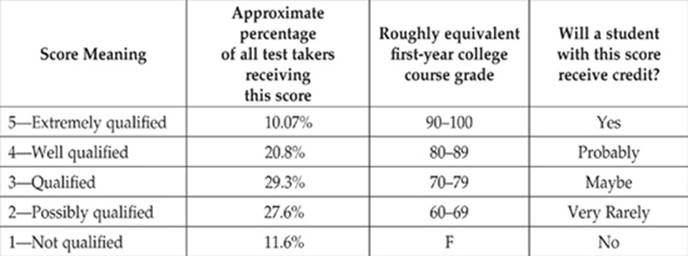

After taking the test in early May, you will receive your scores sometime around the first week of July, which is probably right about when you’ll have just started to forget about the entire harrowing experience. Your score will be, simply enough, a single number that will either be a 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5. Here is what those numbers mean.

YOUR MULTIPLE-CHOICE SCORE

In the multiple-choice section of the test, you are awarded one point for each question that you answer correctly, you receive no points for each question that you leave blank or answer incorrectly. That is, the famous “guessing penalty” on the SAT and SAT Subject Tests does not apply. So, if you are completely unsure, guess. However, it is always best to use Process of Elimination (POE), as discussed in Part II, to narrow down your choices and make educated guesses

YOUR FREE-RESPONSE SCORE

Each AP essay is scored on a scale from 0 to 9, with 9 being the best score. Essay readers (who are high school or university English instructors) will grade your three essays, and the scores for your three essays will be added together. The resulting total (which ranges from 0 to 27) constitutes your free-response score.

We will go into the details of essay scoring in Part III, but in general an essay that receives a “9” answers all facets of the question completely, making good use of specific examples to support its points, and is “well-written,” which is a catch-all phrase that means its sentences are complete, properly punctuated, clear in meaning, and varied (they exhibit a variety of structure and use a large academic vocabulary). Lower-scoring essays are considered to be deficient in these qualities to a greater or lesser degree, and students who receive a “0” have basically written gibberish. If you write an essay that is not on the topic, you will receive a blank (“—”). This is equivalent to a zero.

The essay readers do not award points according to a standardized, predetermined checklist. The essays are scored individually by individual readers, each of whom scores essays for only one prompt. Thus, you will have three different readers, and each reader will be able to see only the single essay that he or she reads. The readers do not know how you did on the other essays or what score you received on the multiple-choice section.

YOUR FINAL SCORE

Your final score of 1 to 5 is a combination of your scores from the two sections. Remember that the multiple-choice section counts for 45 percent of the total and the essay section counts for 55 percent. This makes them almost equal, and you must concentrate on doing your best on both parts. ETS uses a formula to calculate your final score that would take almost a full page to diagram, but it isn’t worth showing here. Given that neither you nor anyone else (including the colleges) will ever know what your individual section scores are, there is no reason to get too wrapped up with the specifics.

If you like statistics, however, here is some useful information: If you can get a score of 36 (number correct) on a multiple-choice section with 54 questions, you have exactly a 99 percent chance of getting at least a score of 3 on the exam.

GETTING CREDIT

So how do you get credit from colleges for taking this exam? First, you must attend a college that recognizes the AP program (most colleges do); second, you need to get a good score on one of the two AP English exams (Language and Composition or Literature and Composition).

Your guidance counselor or AP teacher should be able to provide you with information on whether the schools to which you’re applying award AP credit. They can probably also tell you how much credit you can get and what scores you need to get the credit. You can also sometimes get the information you need from the college’s website. By far the most reliable way to find out what you need to know is to write or e-mail (do not call) the admission office of the schools that interest you and ask about their AP policy. When someone from admission responds, take the e-mail or letter with you when you register for courses (that’s why you didn’t call!). College registration does not always go smoothly, and you don’t want to have to argue with an admission clerk over things like credit (or placement).

In general, the AP exams are widely accepted, but minimum scores and credits awarded vary from school to school. A 4 or a 5 will always get you credit when it is available. A 3 works at many schools, especially larger universities, but unfortunately, a score of 1 or 2 will get you neither credit nor placement.

As you saw from the table, only about 25 percent of the students who take the AP English Language and Composition Exam earn a 4 or a 5, and about 42 percent receive a 1 or a 2. The rest—33 percent to be exact, receive a 3. This isn’t an easy test, but it’s well worth the effort that it takes to do well. And again there’s good news: With so many poorly prepared students taking the test, you can use this book and walk into the testing center with an important advantage.

Just a couple more topics and we’ll move on to strategies and techniques.

HOW TO REGISTER TO TAKE THE EXAM (AND OTHER USEFUL INFORMATION)

This test is administered once a year, in early May, and the fee is $87. Your high school guidance counselor should have all the information you need to sign up to take the AP English Language and Composition Exam. You will have to fill out some forms and make sure the timing of this exam doesn’t conflict with any other AP exams you may be taking. Since you’ll be preparing so much for this exam, it would be a shame to encounter a scheduling conflict on test day.

On test day, be sure to wear comfortable clothes and shoes; consider dressing in layers if you don’t know what the temperature in the testing room will be like. Bring a snack to eat during the break if you think you’ll get hungry. Also, remember to bring at least two number-2 pencils and a few good blue or black pens (those are the only two colors allowed on the AP exam).

Finally, and most important, don’t forget to get a good night’s sleep before test day.

HOW TO USE THIS BOOK

While you may be tempted to skip right to the content review portion of this book—Parts IV and V—we strongly recommend that you read the chapters on test-taking techniques before you work through the content review. These chapters will give you a better idea of what you’re doing and show you important techniques for approaching the sample questions, drills, and two full-length tests.

After you have taken the practice tests, we advise that you read all the explanations, even the explanations to the questions that you’ve answered correctly. Often, you will find that your understanding of a question or the passage will be broadened when you read the explanation. Other times, you’ll realize that you got the question right, but for all the wrong reasons. Also, sometimes you could learn the most from other students, so we strongly recommend that you read the sample essays, which several well-prepared students wrote just days before they took the real exam.

MOVING ON…

At this point, we’ve described the basics of the AP English Language and Composition Exam. You probably have a lot of unanswered questions, such as What are the passages like? What kinds of questions are in the multiple-choice section? How should I approach the essays to ace them? Does good handwriting count? When should I guess?

We’ll answer all these questions and many more in the chapters that follow.