PRACTICE MAKES PERFECT: Advanced English Grammar for ESL Learners (2011)

4 Adjectives

In this chapter we deal with two topics: (1) forming the comparative and superlative forms of adjectives, and (2) deriving adjectives from verb participles.

Forming the comparative and superlative forms of adjectives

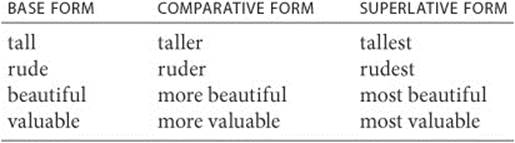

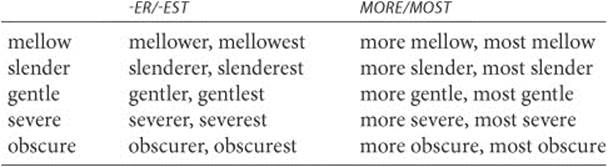

The comparative and superlative forms of adjectives in English are unusual in that there are two different ways of forming them. One way uses the infl ectional endings -er and -est. The other way uses the adverbs more and most. For example:

The reason English has two different ways of forming the comparative and superlative is historical. Modern English is a mixture of two different languages: Old English (Anglo-Saxon) and French. In Old English, all adjectives formed their comparative and superlative with -er and - est. The many hundreds of French adjectives that came into English in the Middle Ages tended to follow the French way of forming comparative and superlative by using adverbs, more and most in the case of English. Since most adjectives of Old English origin are one and two syllables and most adjectives of French origin are two, three, and even four syllables, people gradually came to associate length with the way of forming comparative and superlative forms regardless of historical origin: short words use -er and -est; long words use more and most. As a result, nearly all one-syllable adjectives in Modern English use -erand -est to form their comparative and superlative, and nearly all three- and four-syllable adjectives use more and most. The problem is that we cannot reliably predict how any particular two-syllable adjectives will form their comparative and superlative forms.

We can divide two-syllable adjectives into three groups: a large group that always uses more/most; a somewhat smaller second smaller group that can use either more/most or -er/-est; and a quite small third group that can only use -er/-est.

Two-syllable adjectives that always use more/most

This is by far the largest group. If you are not sure which form of the comparative and superlative to use, your best bet is always more/most. Here are some characteristics of the adjectives in this group:

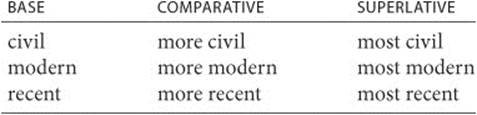

Nearly all two-syllable adjectives that consist of only a single word part (i.e., not built with a stem + a suffi x like, for example, lonely) must use more/most. For example:

Two-syllable adjectives made up of a certain stem + a suffi x or infl ectional ending also must use more/most.

Two-syllable adjectives that use the suffi xes -ful and -less use more/most. For example:

![]()

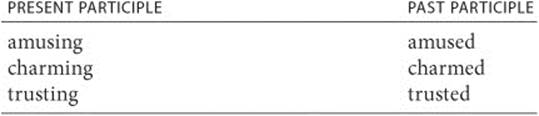

Two-syllable adjectives ending in -ed or -ing that are derived from verbs must use more/most. For example:

Two-syllable adjectives that can be used with either more/most or - er/-est.

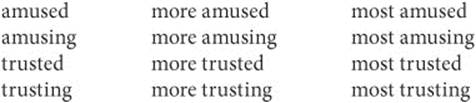

The majority of adjectives in this group end in unstressed second syllables. The largest single group ends in -ly. For example:

Note: The change of y to i follows the same spelling pattern we saw in the plural of nouns that end in -y. For example: baby, babies; lady, ladies.

Adjectives that end in unstressed vowels, -er, -le, -el, -ere, -ure can also use either pattern:

Two-syllable adjectives that can only use -er/-est.

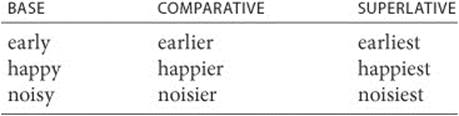

The largest group in this category ends in unstressed -y. For example:

Another group has the meaning of “small.” There is something semantically inconsistent with using more and most with these words. For example:

X I would like something more little.

X I ended up buying the most little rug.

These words use -er/-est:

I would like something littler.

I ended up buying the littlest rug.

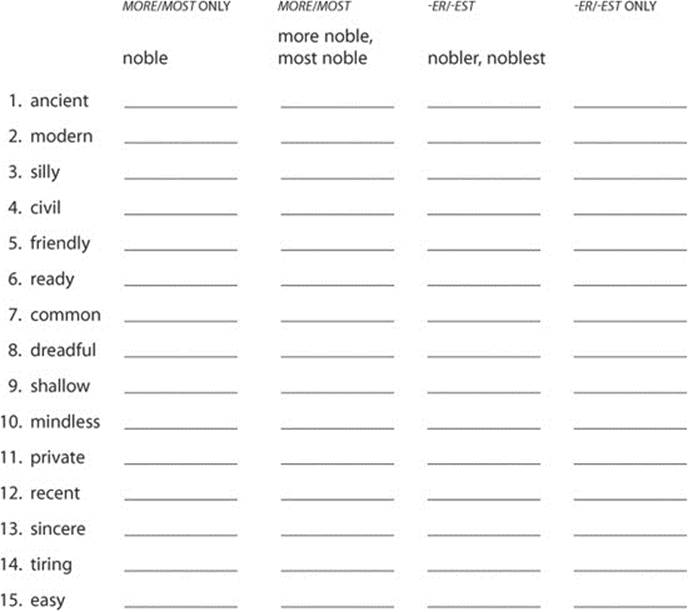

EXERCISE 4.1

Write the comparative and superlative forms of the following two-syllable adjectives in the appropriate column. The first question is done as an example.

Deriving adjectives from verb participles

Most languages form adjectives from verb participles. English is somewhat unusual because it uses both the present participle and the past participle to form adjectives. Here are some adjectives derived from present and past participles:

The adjectives derived from present participles and the adjectives derived from past participles have quite different meanings. For example, compare the following two sentences:

![]()

In the first example, the present participle adjective tells us that Mr. Smith bores his students. In the second example, the past participle tells us the exact opposite: Mr. Smith’s students bore him.

These two participles have such dramatically different meanings because the participles maintain the different relationships that the underlying verb bore has with the noun teacher.

In the case of the present participle, the noun being modified, teacher, functions as the SUBJECT of the underlying verb bore. In other words, the teacher is doing the boring:

![]()

In the case of the past participle, the noun being modified, teacher, functions as the OBJECT of the underlying verb bore. In other words, something or someone (his students presumably) is boring the teacher:

![]()

To correctly use present and past participles as adjectives, you must ask yourself whether the noun being modified is the subject, the “doer” of the action of the verb underlying the participle, or the object, the “recipient” of the action of the verb underling the participle.

Here are some more examples.

After their (thrilling/thrilled) ride, the children could talk of nothing else.

What is the relationship of the noun being modified, ride, to the verb underlying the participles? Did the ride (subject) thrill the children, or did the children thrill the ride (object)? Once you consciously ask the question, the answer is obvious. The ride is the subject of the verb; the ride is doing the thrilling. Accordingly, we must use the present participle:

After their thrilling ride, the children could talk of nothing else.

Be sure you take the (prescribing/prescribed) amount of medicine.

Does the noun being modified, amount of medicine, do the prescribing (subject), or does someone (a doctor or pharmacist) prescribe the amount of medicine (object)? Clearly, the noun being modified is the object of the underlying verb. Accordingly, we must use the past participle:

Be sure you take the prescribed amount of medicine.

The simplest way to decide which participle form to use is to see if you can use the noun being modified as the subject of an -ing form of the verb underlying the participle. If you can, use the present participle. If you cannot, use the past participle.

Here are some examples of the -ing test applied to two new examples:

The new bridge is an (amazing/amazed) structure.

Ask yourself this question: is the structure amazing us? The answer is yes, so we know we should use the present participle form amazing:

The new bridge is an amazing structure.

She proudly waved her newly (issuing/issued) passport.

Ask yourself this question: is the passport issuing something? The answer is no, so we know we should use the past participle form issued:

She proudly waved her newly issued passport.

EXERCISE 4.2

Using the -ing test to pick the right form of the participle, cross out the wrong choice and underline the correct one. The first question is done as an example.

We went to a (charming/charmed) children’s recital.

1. The (discouraging/discouraged) team left the field.

2. It was a very (tempting/tempted) offer.

3. Please play the (recording/recorded) message again.

4. We bought a new (recording/recorded) machine.

5. Her mother was a (respecting/respected) lawyer in the city.

6. The movie is set on a (deserting/deserted) island.

7. He gave a very (moving/moved) speech.

8. The Russians quickly followed Napoleon’s (retreating/retreated) army.

9. Please stay out of the (restricting/restricted) area.

10. The new design incorporates many features of the (existing/existed) building.

11. The company fi red the (striking/struck) employees.

12. We had to replace the (damaging/damaged) curtains.

13. We waived down a (passing/passed) taxi.

14. We got back a very (encouraging/encouraged) response.

15. The (attempting/attempted) coup failed miserably.