Essential Writing Skills for College and Beyond (2014)

Introduction

UNDERSTANDING ACADEMIA

You’ve probably heard people refer to the college campus as “The Ivory Tower.” This is, in some ways, an accurate description of the world and people you will encounter in college. The atmosphere is one of idealism, of the pursuit of knowledge, and of the quest for higher ideals. Mundane, practical matters hold significantly less importance here than in, say, the business world. In academia, the dollar is not paramount, nor is physical appearance, and markers of status, such as expensive clothing, accessories, and various other products, are not essential to success.

In academia, there is a purposeful disconnect from the so-called everyday world, especially in the departments of the humanities (psychology, English, philosophy, music, theater, and so on). In fact, the pursuit of higher knowledge requires this disconnect because it requires you to take on a different mindset than the one in the current mainstream or “everyday world.”

It is important that you begin to cultivate and understand this mind-set. Why? The people and texts you will encounter in your college career will probably be unlike any you have ever encountered, and it can be disorienting if you feel unsure about your role as a student and the purpose of your work. However, this world is not as difficult to navigate as you may think, for it has but one central principle at its core, and once you understand that principle, you can and will excel in academia.

What is this central principle? Consider for a moment why college professors become college professors (instead of, say, accountants or lawyers or dentists). All professors were once college students, and most remained in academia because they fell in love with the search for knowledge, the inquiry into what is known and true, and the desire to find definitive answers. They remain there because they want to continue this quest and meet and work with others who share that goal.

Keep this point in mind as you write your papers and attend your courses because it illustrates the central principle of academia and the base on which it is built: the quest for knowledge.

If you think this principle of “the quest for knowledge” sounds high-minded and philosophical, you’re right; it is. However, it is also a fact—and if you remember and apply it, you will succeed in college. To be successful in college means to reflect in your work this desire to know and to prove.

Remember, academics value, above all, knowledge. Professors seek to examine, to learn, to explain, and to know. They have dedicated their lives not to the pursuit of money, fame, or prestige but rather to the pursuit of knowledge, and they expect their students to seek and present such knowledge as well.

The best way to impress an academic is to illustrate that you understand and respect this principle and that you, too, seek higher, deeper knowledge.

How do you go about doing that?

In your writing, do not merely rehash known information on the assigned topic, subject, or person. Instead, examine, question, and challenge information, theories, and interpretations. Do this, and you will excel in your college classes.

If you’re thinking this point is easier said than done, you are right. However, it’s not as difficult as you think. It begins with taking your role as a student seriously, and clearly you already do or you wouldn’t have taken the time to read this book.

While proofreading and editing your work is undoubtedly important, as you write, keep in mind this larger picture of the quest for knowledge and focus on it, rather than on tiny grammar or spelling errors. Ask yourself what you seek to discover on any assignment, and truly try to find it. This desire to understand will be evident in your work, and it will not go unrewarded. Any small errors in punctuation or grammar that you make will seem minor and will likely be forgiven if at the heart of your work stands a writer who obviously holds a deep respect for the quest for knowledge.

UNDERSTANDING THE ACADEMIC ESSAY

Many students have heard horror stories from friends or older siblings about college essays requiring “research” or “scholarly sources,” and many students enter their classes with one fearful question: “Will we have to do research?” The answer is almost always yes— but don’t let research scare you.

Professors do not expect you to know every text or idea within a certain topic—and certainly not within an entire field (such as biology, literature, or philosophy). Your instructors will expect you to show respect for the quest for knowledge by demonstrating within your work that you have read and understand other key scholars’ ideas.

The essence of the college essay contains three major parts; be sure your essays contain all three:

· Your ideas

· Their (other scholars’) ideas

· The connections between your ideas and their ideas

Or, if you think mathematically, imagine this as an equation:

Your Ideas + Their Ideas + Connections Between Your Ideas and Their Ideas = Successful College Essay

Tackle each of these parts one at a time. Most students find the entire writing process to be much easier when they move from one part to the next rather than trying to simultaneously complete all three parts. In fact, the organization of this book reflects and illustrates this principle.

You’ll notice this book begins with helping you develop your own ideas first. However, this organization is not to suggest you must begin every essay with this step. Some students prefer to do research first and then develop their own ideas. Try both methods and see which works better for you.

ACING THE ACADEMIC ESSAY

Regardless of the type of writing your instructors assign, remember that a successful academic writer aims to achieve two goals: It should be both credible and interesting.

These two aims are indeed listed in order of importance; if you cannot write an engaging, interesting essay, then at least be sure to write a credible one.

To write a credible essay:

· ADDRESS AND ANSWER THE PROMPT. Ensure your essay remains focused and on topic through each paragraph.

· CITE THE WORK OF KEY THINKERS IN THE FIELD. Consult your professor, librarian, or teaching assistant to find out who these people are and how to correctly cite them.

· GO ABOVE AND BEYOND THE CALL OF THE ASSIGNMENT. If the instructor does not require outside sources but you include and properly cite them anyway, you and your work will stand out as superior.

· PROOFREAD. Do not have spelling, grammatical, typographical, or punctuation errors.

· GO TO OFFICE HOURS. Speak directly with your professor to show you take the class seriously.

To write an interesting essay:

· BE CONTROVERSIAL. Take a different stand than other writers (especially your classmates).

· EXPERIMENT WITH YOUR WRITING STYLE. Vary your sentence structure and word choice, and don’t be afraid to experiment and take risks; often, innovation is well worth the risk.

· CONSIDER—AND CHALLENGE—THE ASSUMPTIONS AND THEORIES OF OTHERS. Successful academic writing requires engaging with the ideas of others, not just presenting your own. It is crucial that you learn how to consider and respond to others’ work.

Granted, some of these strategies can be risky, and not all professors will admire your attempt to experiment with language or form, debunk their favorite scholar’s theory, or write about a controversial topic. If you’re planning on experimenting or being controversial, show your instructor your draft during office hours. You’ll be able to tell immediately if he finds it distasteful. If so, tuck it away and save it for another semester. If not, feel free to proceed.

HOW TO GET STARTED

THE STUDENT-FIRST VS. THE SCHOLARS-FIRST MODEL

Many students struggle with beginning the writing process. Essentially, two models exist that can help you begin: the student-first or the scholars-first models. Choose one or both of the following strategies to help develop your own ideas as well as find and incorporate the ideas of others into your essay.

THE STUDENT-FIRST MODEL

1. The student writes out and determines her own ideas on the topic first, without deeply considering the work of other scholars.

2. The student begins examining other scholars’ ideas to compare and contrast those with her own. The student may or may not alter her original viewpoints, but she must include the work of others in her essay.

THE SCHOLARS-FIRST MODEL

1. The student examines other scholars’ ideas before exploring his own to get a firm grasp on the major ideas or theories within the assigned topic or text.

2. The student focuses on developing his own opinions, beliefs, and evidence. The student may or may not agree with the scholars’ ideas, but he must include them in his work.

WHICH MODEL IS BETTER?

The answer depends on the writer and perhaps on the topic. If you receive a topic you know absolutely nothing about, then you may want to try the second strategy. However, if you already have many ideas or opinions on the topic, then the first strategy may work better for you.

Most colleges and universities employ the “Scholars-First Model” in their classes. Instructors typically have students read the best and/or current research on a topic. Then they require students to write a paper based on their understanding and/or opinion of that research and topic. Both models work, though, so try both and see which one works best for you.

Types of Academic Essays

In your high school classes, you may have written the following “types” of essays:

· Informative

· Persuasive

· How-to or instructional

· Personal or reflective

· Analytical

· Comparison/contrast

The good news is that the skills you gained in writing these essays won’t go to waste; you’ll absolutely use these abilities in your college writing classes. Keep in mind, however, that most of these essays do not exist singularly in the college environment as they did in the high school classroom. In other words, professors will not label the type of essay they assign; they will simply write an assignment, hand it out, and expect you to understand the assignment and complete it. The essays they assign probably won’t focus on a single skill (such as comparison/contrast or persuasion).

The typical college writing assignment requires all the skills employed in all the essay types learned in high school.

For example, a persuasive collegiate essay typically requires writers to inform, include, or build on personal anecdotes or experience, compare and contrast different scholars’ opinions or theories, analyze research, and persuade.

Unless you attended a very progressive high school or GED program, this type of writing will probably be both new and challenging for you—at first. Don’t panic, though; writing is like most other tasks; with time and practice, it will get easier.

Also, remember that professors do not expect you to turn in an essay worthy of Shakespeare, Faulkner, or Plato, especially in a freshmen composition course. They do expect students to spend the necessary time ensuring their work meets the requirements of the assignment. If you feel uncertain about whether you have included all the necessary information, go to your professor’s office hours and ask the instructor to look over your work. A simple office visit can mean the difference between an A or a B or even passing versus failing.

UNDERSTANDING THE PROMPT

The writing prompt is the set of instructions you receive from your instructor dictating the requirements of the assignment. The prompt tells you how to succeed on the assignment—and how to fail.

Most beginning students quickly read the prompt and then toss it aside in their fervor to get started on the essay. Don’t commit this cardinal sin!

Don’t just glance at the prompt, toss it aside, and never reread it again. Keep it with you as you write, and refer to it often.

This advice is especially important because college writing prompts are sometimes complicated, long-winded, and downright persnickety. One quick read-through is probably not sufficient to fully and comprehensively understand the assignment.

Read the prompt carefully. Highlight or underline the key terms, and ask questions if necessary to make sure you fully understand the assignment before you actually start writing. Refer to the prompt as you write to ensure your work actually addresses the question(s) posed.

You might be surprised by how many students waste time writing a paper that does not meet the assignment. When these students receive their low—or even failing—score, they become frustrated not only with that particular assignment but with the class in general. Investing the time necessary to understand the assignment will actually save you time, not to mention frustration.

Specifically, make sure you understand (at minimum) the following:

· What type of writing is required? (Persuasive? Informative? Both?)

· What is the central question, issue, or problem you need to address?

· Do you need to include outside sources? What kind? (Books? Articles? Both?)

· What type of documentation style do you need to use? MLA (Modern Language Association)? APA (American Psychological Association)?

· How many quotes should you include from in-class readings?

· Do you turn in a physical copy or an electronic copy? Both?

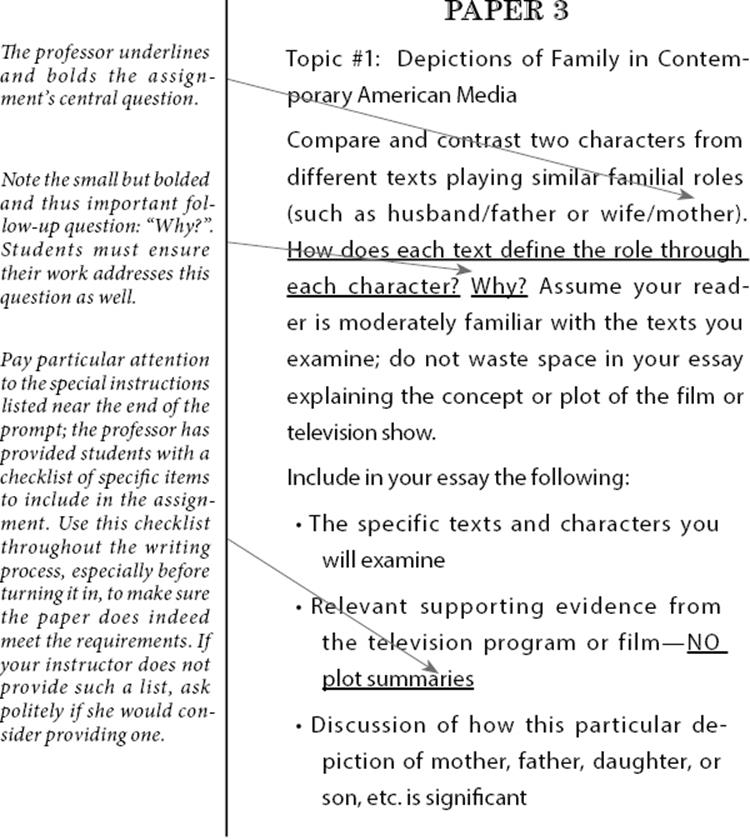

In the following sample college-level writing assignment, notice that the instructor provides students with clear indicators (bold and underlined) of the most important elements of the prompt. Not all professors will take the time to make their assignments this clear. Many do, though, so pay particular attention to items bolded, underlined, or otherwise emphasized in a writing assignment.