The Complete Idiot’s Guide to Speed Reading (2008)

Part II. Get In, Get Out, and Don’t Go Back

Chapter 7. Getting In

In This Chapter

• Are you right-brain or left-brain dominant?

• Giving you the what for

• The view from the top

• Nonfiction reading made easy(er!)

• Getting in to technical material

When you realize that more than 18,000 titles of magazines are published in the United States every year, the concept of reading everything takes on a new meaning! If you did want to read it all, you’d be reading about 50 magazines a day, many of which would be of no interest to you. Instead, it’s important—and time-saving—to read only things of value to you.

In this chapter, I first want to help you decide whether or not you should even get into a piece of reading material and when you do, how best to approach it. In Chapter 14, I show you specifically how you can create a personally valuable reading workload. (If this type of planning is what slows down your reading, you might want to read Chapters 7 and 14 consecutively.)

Nonfiction, Fiction, and Your Brain

If you ask people what they like to read, some will say “I like a good novel,” while others will say “I like to read for information.” This tells you the former prefer fiction while the latter prefer nonfiction.

def·i·ni·tion

Works of fiction consist primarily of literature whose content is produced by the imagination and is not necessarily based on fact; novels and short stories fall in this category. Nonfiction gives facts and information; newspapers or magazines are examples of nonfiction. Most business reading is considered nonfiction. Books can be either.

But there’s more at work here than reading for a story or plot or reading for facts. Believe it or not, how you think reflects what you prefer to read.

Reading and Your Dominant Brain

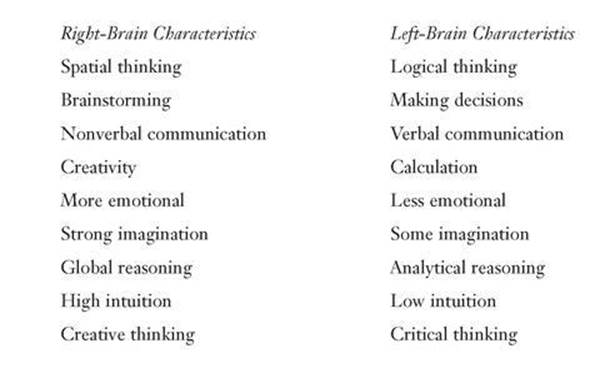

Roger Sperry, a pioneer in conducting behavioral investigations of the brain’s two hemispheres, concluded many things based on his work. One of his conclusions is that everyone is either right-brain or left-brain dominant.Everyone has some ability from both sides of their brain, however, Roger Sperry thinks that everyone has a dominant, or stronger, side.

Left-brain dominant people are considered efficient. They like being organized and show a high regard to time. They enjoy learning details and want one correct answer. They crave routines and are good at making decisions. Many left-brain dominant readers prefer to read more nonfiction than fiction.

Right-brain dominant people tend to be disorganized (maybe even messy) and pay little attention to time. They like to see the big picture of concepts before getting into the details and want to see several possible answers to a question. They enjoy the concept of play and are considered somewhat impulsive. Many right-brain dominant readers prefer to read fiction.

The following list contains more characteristics of both sides of the brain. Compare the two sides and see which side sounds more like you.

Fiction Versus Nonfiction

When you were young and just learning how to read, you probably started with fiction. For most people, fiction is easier to read because it engages the brain visually (your mind’s eye pictures what you’re reading), auditorily (you hear what the characters say in your head), and kinesthetically (you mentally experience what the characters experience). It’s like your own movie playing in your head while you read.

Nonfiction can be more challenging. Many students who initially loved to read soon find less pleasure in reading sometime around middle school, when textbooks—nonfiction textbooks—become the primary learning material. Textbooks and other nonfiction don’t engage the brain visually (although pictures might appear in the book), auditorily, or kinesthetically. Instead, they engage your brain digitally, providing data and information. This is one of the main reasons reading nonfiction is more challenging than fiction.

Speed Secret

Fiction and nonfiction are different types of reading material that require different approaches. Understanding how to apply the strategies to the different materials makes you a more flexible and skilled reader.

Remember Why and Add What For

In Chapter 2, I introduced you to the concept of identifying the reason why you’re reading so you’ll know, before you begin, what you want to get from the reading material. Answering why directs your reading by helping you look for specific information. Why are you reading this? Not having a good enough answer to your why question tells you that you should find something else to read that does!

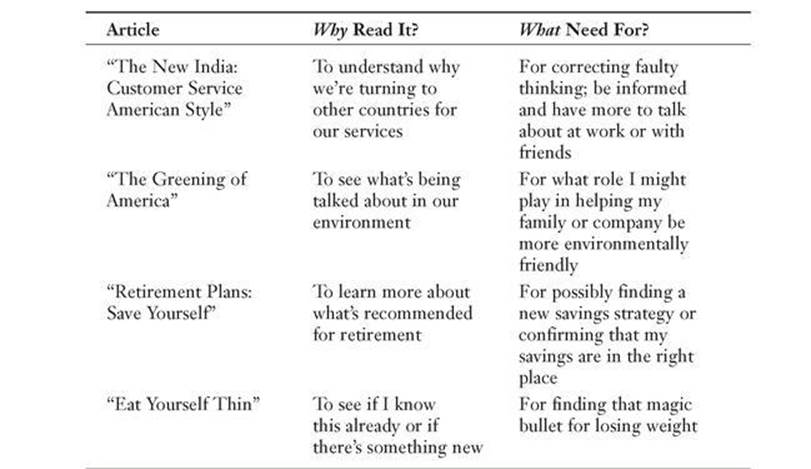

Now let’s add another idea to the why: “What might I need the information for?” The following table lists some sample article titles, reasons for reading them, and how they might be used.

Speed Tip

Not all parts of a book have equal value to your why and what for questions. You can fast-forward or skip when reading a book if the material isn’t worth your full time and attention.

There are many more reasons for reading, like being informed in meetings, being up to date for predicting trends, or finding a new strategy to better manage your employees (or your kids!). What reasons can you come up with for why you read?

Knowing your reasons for reading engages your brain and definitely puts you on the track to faster reading.

Getting a Bird’s-Eye View

It’s time to do a timed practice to build your speed reading skills. Although I include this here, you can always do a timed practice whenever you want. You don’t have to wait for me to suggest it!

Note: nonfiction is more challenging to read, so the next few sections deal specifically with this type of reading material. Find a nonfiction book or magazine to keep handy for use in this chapter. You could even use this book if nothing else is easily available to you.

Pretend you have a nonfiction book on time management in front of you. You’ve never seen it before but are interested in reading it. You chose the material because a friend recommended it (your why) and you want to find some ways to manage your time better (your what for). You think you’re ready to read. But wait! You’re not quite ready yet!

It’s just like visiting a new town you’ve never been to before but are interested in visiting. You’re in the town because a friend said it was quaint (your why) and you want to take photos of the more interesting sites (your what for). You could start walking in the town, street by street, hoping to come upon something good to take a picture of, or you could go up in a helicopter to get a bird’s-eye view of the town, quickly finding some neat old buildings and town landmarks to photograph.

Obviously, you’re not going to take a real helicopter ride, but if you did, you could see the entire town in much less time than it would take you to walk it. And when the copter lands, you’d know exactly which direction to head to get the photos you want. A big time-saver!

If you were to just start reading when you were “ready,” you might start reading from the beginning, word for word (like walking street by street). Or instead, you could hypothetically go up in your helicopter to get a bird’s-eye view of the material, looking for valuable information based on your reason why and what you are reading for.

So what should you look for when you’re up in your hypothetical helicopter? Here are the biggies:

Copyright date This lets you know how current, or not, the material is. It puts the information into historical context.

Table of contents This gives you the outline of the book/magazine and what topics you might want to read about.

About the author This information tells you about his or her expertise, where he or she is coming from based on their experiences, and what you might expect to find in the material. llustrations or photos A picture is worth a thousand words, especially if it has a caption, and quickly provides clues to the reading content.

Quotes and information placed in the margin This material usually reflects something valuable.

Speed Secret

Using this bird’s-eye view approach to your reading material is a lot like putting together a jigsaw puzzle. Looking for this easily identifiable information first is like looking for the corner pieces and straight edges of the puzzle.

Not all these areas are present in everything you read, but see which apply to your sample material. After reading about the areas, take a few minutes to flip through your material to locate these areas.

This quick overview helps you decide where you want to go in the reading and where to spend your time, if at all. This deliberate and general view is explained in greater detail in Chapter 10.

Where’s the Meat?

Speed reading involves using your eyes and brain to process words more rapidly. In addition, speed reading means being able to find the most important information quickly. I call the most important information the “meat,” and consider the other explanation and details the “potatoes and veggies.” When speed reading, you should look for the meat first and leave the potatoes and veggies for later.

In elementary school, when you first learned to read, it made sense to read from the beginning of the chapter or article to the end. Now, as an adult, if you continue to read this way, you might be wasting a lot of time reading information you have no need for. This may come as a surprise to you but reading is not a linear activity! You don’t have to read from the beginning to the end to say you read something. You do, however, need to find and read what’s most important—the meat.

So where do you find the meat? Think back to high school, where you (hopefully) were taught how to write essays. Before writing the essay, you had to do some research, come up with a thesis statement, and create an organizational structure called an outline. You were also taught that every essay contained three parts: an introduction, a body, and a conclusion. Most published nonfiction material you read follows this basic three-part outline structure.

Why should you be interested in this? Because every piece of published nonfiction has an outline—and the most important details are in the outline—so it’s in your best interest to find it before you read!

I affectionately call the process of finding the writer’s outline cheat reading. I use this term because many times, depending on your why and what for, you don’t need to read more than the outline to get the information you need. It’s also used to introduce you to the writer’s structure and flow so you can better understand the point when the material is technical or unfamiliar.

def·i·ni·tion

An outline is an ordered list of the essential features or main aspects of something discussed, usually organized in headings and subheadings.

It’s Okay to Cheat Read!

If cheat reading means finding the meat, or the author’s outline, you need to know where to look for it. Start with these areas:

• Title

• Introduction

• Subheadings

• First sentence of every paragraph

• Conclusion

Speed Bump

Most published nonfiction has been edited, which makes it easier to find the writer’s outline. When reading unedited documents and e-mails written by your colleagues and other nonpublished writing, it might be more challenging to pinpoint the outline.

Unlike fiction, the title in nonfiction generally reflects the subject or theme of the material.

The introduction points you in the direction the author wants to lead you. An introduction may consist of just the first paragraph or several paragraphs, or if there is a subheading, the introduction usually ends at the first subheading. Once you know where the material is headed, you can move on. (Yes, I am giving you permission to not read it all!)

The subheadings are the legs of the outline. They provide the ordered structure where the writer’s central ideas are found. When you come upon a subhead, you know you have entered a new subtopic area.

The first, or topic, sentence of every paragraph is so important it warrants its own section. Read the following “Focus on the Firsts” section to see why!

The conclusion, typically the last paragraph or two, summarizes the ideas presented.

For a very broad overview of your material, you can read the title, the introductory paragraph(s), the subheadings, and the conclusion. But if you want a lot more substance in your reading, read the first sentences of paragraphs.

Focus on the Firsts

The first sentence of every paragraph, or the topic sentence, is the most important part of cheat reading. You may know this already, but it’s worth repeating:

The main idea of almost every nonfiction, published paragraph is found in the first sentence of the paragraph.

By reading just the first sentence of every paragraph in the order written, you’ll find the meat of the writer’s outline.

def·i·ni·tion

The first sentence of a paragraph, where the author wrote the main idea, is called the topic sentence.

So if you want to get the main ideas quickly without wasting time, read the title and the first few paragraphs of introduction, and then stop reading all the rest of the words. Read just the first sentence of a paragraph, get the idea, and move on to the first sentence in the next paragraph. Continue doing this until you feel you’ve read enough based on your why and what for, or until you reach the last few paragraphs. Be sure to read the last few paragraphs fully because they typically serve as the conclusion of a nonfiction piece.

Reading firsts helps you …

• Find and retain the answers to your what for question.

• Familiarize yourself with the writer’s structure so you can choose which paragraphs to read in more detail.

• Quickly weed out uninteresting or uninformative material.

• Build a mental framework that makes it easier to remember.

• Save time—perhaps the most important reason of all!

Speed Tip

If you can’t find the main idea in the first sentence, you can try a couple other places. Some authors like to put their main ideas in the last sentence. Rarely will you find it buried in the middle. Sometimes, the first sentence of a paragraph is more fluff than information. In such cases, it’s okay to move on to the second sentence. But remember, you only want to read into the paragraph just enough to get the main idea and then get out!

Where to Look for Other Clues

Some other clues can indicate what’s important in a piece of writing. When looking for the writer’s outline, also look for these (some of which I briefly mentioned earlier):

• Pictures, illustrations, graphs, or charts

• Captions

• Anything pulled out in a margin or box

• Bold or italic print

• Bulleted and numbered lists

• Length of the article

Pictures, illustrations, graphs, or charts are visual representations of the author’s ideas. Many times, these help solidify your understanding of a concept written about in the text. Speed read by reading the pictures!

Captions are text descriptions of the pictures that clarify what you’re looking at. Sometimes a picture with a caption is all you need to understand what’s being described in the text.

Depending on the material you’re reading, you might find things placed in the margin such as an important quote from the article or a definition of a term discussed. These are pulled out of the text because the information has been deemed useful and important.

Bold and italic print draw your eyes to important information. In academic textbooks, a bold word indicates a new vocabulary word and italics shows a point of emphasis. In other nonfiction, bold may be something the author wants to draw your attention to and italics may show an important description or point of emphasis. Both are worth noting when cheat reading.

Bulleted and numbered lists are examples from a main point. Earlier in this section, for example, the bulleted list gives you the “outline” or overview of where to look for other clues in the writer’s outline. In this case, each paragraph that follows explains each point.

Looking at the length of the article is useful for time management purposes. If you have 10 minutes to read and you want to read a 17-page article, you might decide to cheat read it first so you can get through more of it in the time you have. Or if you have a 30-page textbook chapter, you might want to break it down into smaller sections, making it easier to follow the writer’s outline.

So how can you best use all this information for your reading needs? Perhaps just knowing that the main ideas of paragraphs are typically located in the first sentences (or two) empowers you to focus your attention there. Or perhaps understanding that the introduction and conclusion should provide you with where the reading intends to go and where it ends up will help you get what you need quickly. Using this cheat reading process as a guide, not a strict procedure, helps you identify the most important ideas, quickly!

Speed Tip

When pressed for time, sometimes you’re better off doing a first sentence cheat read than reading everything really, really fast. For example, you have a document with 20 paragraphs. You could read the first sentences of all 20 paragraphs in the same amount of time you could read just the first 20 sentences. You’d understand more and have a better overview of the main points of the entire article rather than just the first 20 sentences.

Cheat Reading Made Easy

Here’s an easy exercise in cheat reading. After reading these directions, be prepared to time yourself for 2 minutes.

1. Using your chosen nonfiction magazine or book, turn to the table of contents and locate an article or chapter you’d like to read.

2. When you start timing, read the first paragraph or two of the introduction in its entirety. Remember to practice with your favorite speed reading strategies!

3. Then stop reading everything and focus your attention on just the first sentence of the next paragraph down, then skip to the next first sentence of the next paragraph down, and continue on. Remember, you are only looking for the writer’s outline, not all the details.

4. Look around for other clues such as pictures, captions, bold, or italics.

5. If you reach the end of the material before the 2 minutes are up, read the last concluding paragraph in its entirety.

6. At the end of the 2 minutes, close the reading material and on a separate piece of paper, write a summary of what you just read. Spend at least 2 minutes doing this. You can write in either bullet points or sentences.

Did you find the writer’s outline? From my experience, it’s there about 95 percent of the time on edited material. As for the other 5 percent, that’s usually either poor writing or poor editing. You’ll come across this at some point, but more often than not you’ll find the outline.

Did you get farther in the 2 minutes than if you read every word? Did you get a general understanding of the article? Hopefully you did because you were reading the writer’s outline.

What you didn’t get were the details, or the explanation, of the writer’s main ideas. The meat you find when cheat reading consists of about 50 percent of the content, while the remaining 50 percent consists of details and explanation.

Speed Tip

When cheat reading in the future, you can figure out how much time you might want to spend on a chapter or an article by multiplying the number of pages by 15 seconds per page. You may cheat read in less time or more, depending on your speed reading strategies and the number of words on a page, but 15 seconds is a good starting point for calculating your time.

By learning how to locate the writer’s outline, you can accomplish any or all of the following:

• Weed out unimportant or not useful material, quickly!

• Find the important information, quickly!

• Be introduced to difficult, technical, or unfamiliar material by first cheat reading the writer’s outline and then allowing you to feel more comfortable approaching the details.

• Pick and choose the area(s) you want to spend your reading time on.

• Create stronger long-term retention through repetition. Cheat reading first and then reading in more detail provides you with the built-in repetition needed to build strong retention. (See Chapter 9 for more on reading and memory issues.)

• Quickly review something you read a while ago, revisiting the main ideas without rereading it all.

Speed Tip

When I teach high school and college students, I suggest that instead of rereading the chapters before exams, they cheat read the chapter, solidifying what they do know while looking for material they don’t know and need to focus on. This allows them to study and still get sleep before the exam.

I credit cheat reading for allowing me to stay current with the magazines I regularly read. Even if I had the luxury of time to slowly pour over every word in the material, I still wouldn’t because this strategy provides me the immediate gratification of getting the information I need in less time. That enables me to read more … and there’s always more! I also use cheat reading for reading newspaper articles and nonfiction books. I tell you how in Chapter 10.

Cheat Reading Fiction

Cheat reading is a strategy used solely for nonfiction because there’s a predictable structure inherent in that type of writing. Fiction has a very different structure and, therefore, needs to be read differently. That’s the beauty of fiction!

There are certainly things to consider when reading fiction, such as identifying the basic elements, analyzing its literary characteristics, and tracking the characters. Chapter 10 dives into fiction in more detail.

Approaching Technical Material

I’ve noticed a strange but common occurrence with many people I’ve taught to speed read: they start reading something technical or unfamiliar and begin “studying” it. This only makes their brain work harder than necessary. Study reading is done at a very slow speed and typically entails reading word for word in an effort to memorize.

I’ve seen these same people struggle with technical material because they have little to no understanding about what they’re reading. How can you remember something when you haven’t even figured out what the material is about? No wonder technical material isn’t fun to read.

Take my advice: don’t read to remember; read to understand. Creating usable memory requires having some general understanding. Once you understand, you have a much better chance of remembering.

When you approach material you consider technical, do you immediately think This is going to be hard? Don’t think that! Instead, remember what you’ve learned thus far and approach technical material, or any completely new information, with smart reading strategies. Try cheat reading, reading the bigger words or thought chunks, or using a hand or card pacer method. Each of these techniques, when skillfully combined, make a difficult reading task into a less challenging, more efficient one.

def·i·ni·tion

Study reading is anything you read and learn from that you need or want to use later on. For students, it’s usually for tests and papers. For businesspeople, it’s typically for sharing at meetings, writing reports, and giving presentations. Some people just like to learn new things so they spend time study reading what they’re interested in.

And the Results Are …

If you read through this chapter without trying to actually cheat read, that’s considered cheating! Knowing about the concept is different than personally experiencing it. Try it now, it only takes 4 minutes to do—2 minutes to locate the writer’s outline and 2 minutes to write down your keepers. If you already did the exercise, consider doing it again on other material. The more experience you have doing this, the more comfortable you’ll become making it a regular habit.

The Least You Need to Know

• Nonfiction is more challenging to read than fiction.

• Before reading anything, ask yourself why you are reading and what are you reading for.

• Get an overview of nonfiction to help you know where you want to spend your time.

• The most important information in nonfiction is located in the first sentence of every paragraph.

• Cheat reading enables you to get through more reading in less time.

• When approaching technical material, read to understand first and then read to remember.