World Literature

G. K. Chesterton

BORN: 1874, London, England

DIED: 1936, Buckinghamshire, England

NATIONALITY: British

GENRE: Poetry, fiction, nonfiction

MAJOR WORKS:

The Wild Knight and Other Poems (1900)

The Man Who Was Thursday (1908)

Orthodoxy (1909)

The Innocence of Father Brown (1911)

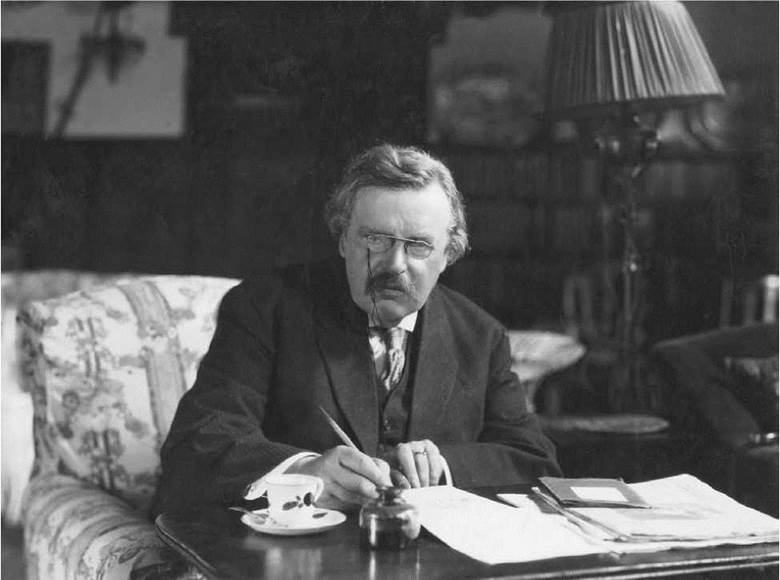

G. K. Chesterton. Hulton Archive / Getty Images

Overview

Regarded as one of England’s premier men of letters during the first third of the twentieth century, Chesterton is best known today as a colorful character who created the Father Brown mysteries and the fantasy novel The Man Who Was Thursday. His witty essays have also provided delight and inspiration to generations of readers.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

A Joyous Childhood in Kensington. Gilbert Keith Chesterton was born in the London borough of Kensington to Edward Chesterton, who owned a real estate business, and Marie Louise Grosjean Chesterton. The religious atmosphere of his middle-class family was more liberal and Unitarian than Anglican, and religion seems to have played no important part in his early life. At the same time, Chesterton’s childhood was a time of intense happiness, and he always claimed that this happiness provided him with an essential religious insight into the meaning of adult life.

His early schooling and his years at St. Paul’s School (1887-1892) seem to have been in general a continuation of the undisturbed happiness of childhood. He was not regarded as a good student, but he made friends at school and did a good deal of writing for a school paper called the Debater, the journal of a debating club he had organized. But his real talent was believed to be his ability to draw. Consequently, instead of following the rest of his friends to university, he went to a drawing school, first at St. John’s Wood and then in 1893 to the Slade School of Art.

From Pictures to Letters: A London Career. When he left the Slade School in 1895, Chesterton worked as a publisher’s reader for two different companies and contributed an occasional poem, article, or art criticism to journals such as the Clarion, the Speaker, and the Academy.

Chesterton was first noticed in 1899 for his contributions to the Speaker, a radical liberal magazine. By early 1901 Chesterton was also established as a regular Saturday columnist for another liberal journal, the Daily News, where his weekly article quickly became a feature of Edwardian journalism. The enormously popular ‘‘Notebook’’ articles in the Illustrated London News began to appear soon afterward and continued almost without interruption from September of 1905 until his death in June of 1936. At the same time, he began to produce biographies, novels, and books of literary and theological criticism that consolidated his reputation as a literary journalist and religious teacher.

Christianity and Chesterton’s World of Fiction. The best known works of this time were his 1908 fantasy novel, The Man Who Was Thursday, and the very popular series of short stories involving a ministerial sleuth, the ‘‘Father Brown’’ mysteries, first introduced in 1910. Both were reflections of Chesterton’s own experiences with religion and spirituality. In The Man Who Was Thursday, a man secretly working for Scotland Yard infiltrates a group of anarchist masterminds in an effort to destroy the organization. Though the book is superficially about anarchists—those who reject laws and governments in favor of complete free will—the book relies heavily on Christian symbolism and imagery. This same preoccupation with Christianity is found in Chesterton’s most famous character, Father Brown. The clever priest who uses his reasoning and intuition to solve crimes was based on an actual priest Chesterton knew named Father John O’Connor. O’Connor ultimately convinced Chesterton to convert to Catholicism in 1922.

Witnessing and Politics. Although he met his friend and colleague Hilaire Belloc in 1900 and was married to Francis Blogg in 1901, the years immediately prior to World War I were a time of political crisis and personal strain for Chesterton. In 1913 his brother Cecil was convicted of the criminal libel of Godfrey Isaacs in connection with a press campaign waged by the New Witness magazine against various politicians and stockbrokers involved in the Marconi insider trading scandal. As Maisie Ward points out in her biography of Chesterton, the case became almost an obsession with him for the rest of his life. His disillusionment with official English political life was now complete, and the tone of his political writing became increasingly bitter and acrimonious.

A good example of this is ‘‘A Song of Strange Drinks’’ (1913), which first appeared in the New Witness. Although this poem is usually read as an example of pure nonsense verse, in fact it is sharply satirical, and its publication led to Chesterton’s dismissal from the Daily News.

A Decline in Health and England’s March Toward War. The bitterness of these years also affected Chesterton in other ways. His health began to deteriorate rapidly. Many events contributed to this breakdown. He became more and more alarmed at events in Ireland, where a situation close to civil war had been developing. In 1913 he began writing a series of articles for the Daily Herald, which are among the most violent articles he ever wrote. The outbreak of war in August added even more serious worries. By late autumn of 1914, under the double burden of anxiety and overwork, his health began to fail. The last of the Daily Herald articles appeared in September of 1914, and by November he was critically ill. The collapse of his health was both physical and mental. By the end of November he had fallen into a coma, which seems to have been caused by some form of kidney and heart trouble. He did not begin to recover until Easter of 1915.

Chesterton’s return to health was very gradual. His illness marks a great division in his life as a writer and an even greater division in his life as a poet. From 1915 onward, he devoted himself more and more to a different kind of journalism that left him little time for imaginative writing. Almost as soon as Chesterton fully recovered from his illness in 1916, his brother Cecil joined the army. In his absence, Chesterton took over the editorship of the New Witness, and he continued to edit this magazine and others until his death in 1936.

Although he did not participate directly in World War I himself, Chesterton bore witness to a generation of young men returning from mainland Europe spiritually and physically broken. His own life ended suddenly on June 14, 1936. He had again gradually fallen ill during the preceding years, even though there had been few signs of any slackening of his literary activity during that period.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Chesterton's famous contemporaries include:

George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950): Irish playwright who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1925 and is best known for his wit and social satire.

Hilaire Belloc (1870-1953): This English poet was a good friend and collaborator of Chesterton's.

Albert Schweitzer (1875-1965): Schweitzer, a French theologian and Nobel Peace Prize winner, put his ''Reverence for Life'' philosophy to work by building a hospital in Gabon, Africa.

Carl Jung (1875-1961): Drawing heavily on the work of Sigmund Freud and of anthropologists looking at social symbol systems and mythologies, this Swiss psychiatrist was the founder of analytical psychology.

Clarence Darrow (1857-1938): An American lawyer and civil rights advocate best known for his work with unions and his defense of Tennessee teacher John Scopes at the famous Scopes ''Monkey'' trial of 1925, in which Scopes was brought up on charges for teaching the theory of evolution in his classroom.

Works in Literary Context

As a literary journalist, Chesterton was very much in the tradition of the Victorian sage. He was at once a teacher and a literary artist. He sought to change society through his teaching, using symbol, parable, and religious allegory as the most effective way of doing so. Chesterton’s verse, therefore, must be read as part of the vast journalistic effort whereby he sought to influence the thinking and the feeling of his age. At the same time, it is important to understand the special character of this influence.

A Spiritual Literary Figure. Like his close friends George Bernard Shaw and H. G. Wells, he preferred the role of teacher and prophet to that of literary man, but unlike them his vision of life was fundamentally Christian and even mystical, and the influence he sought to exercise through his writings was directed toward a social change that would be thoroughly religious. In this sense, he may be more aptly compared to the tradition of spiritually oriented literary journalism later represented by C. S. Lewis. Hence, the themes of many of his most characteristic poems are religious; likewise, his religious verse also has a strongly political tone.

In his poetry, as in his other writings, Chesterton saw himself as a spokesman for the poor and the exploited, whom he regarded as the mystical symbols of God’s presence in the world. The purpose of his verse and of all his writings was to help create a society that would have a deep religious respect for ordinary people.

Distributism. A centerpiece of this purpose was the social philosophy that Chesterton called Distributism. Economically, distributism meant a property-owning democracy in which private property would be divided into the smallest possible units. Socially, distributism aimed at creating a feeling of community and neighborliness among ordinary people, in contrast to the feeling of alienation created by huge impersonal systems such as state socialism and monopoly capitalism (to be succeeded by modern corporate capitalism). Such systems, in Chesterton’s view, treated ordinary people as interchangeable units. Chesterton’s perspective on such matters anticipated the sort of Catholic socialism that would become particularly prevalent in Latin America over the course of the twentieth century.

Irreverent Paradox. Chesterton is recognized as a master of the irreverent paradox, and a recognition of this is crucial to understanding his work. Through paradox, the seemingly self-evident is turned upside down, causing readers to view their initial beliefs in a different light. The shedding of a different light was part of Chesterton’s purpose, and the irreverent or humble paradox was, he said, his ‘‘chief idea of life.’’ His essay ‘‘A Defense of Nonsense’’ perhaps best summarizes his views on this method: “Nonsense and faith (strange as the conjunction may seem) are the two supreme symbolic assertions of the truth that to draw out the soul of things with a syllogism is as impossible as to draw out Leviathan with a hook.’’ In this, Chesterton finds himself in the very good company of philosophers ranging from Erasmus to Soren Kierkegaard.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

One of Chesterton'ss defining characteristics was his use of paradox to illustrate his point. Here are a few other works that use irreverent, sometimes even silly paradoxes to communicate and explore important points about life.

The Importance of Being Earnest (1895), a play by Sir Oscar Wilde. Rhetorical and situational paradoxes abound in this drawing-room comedy by the great Irish wit.

''The Library of Babel,'' (1941), a short story by Jorge Luis Borges. In this fantastical story, a library contains every possible variation of a single 410-page book. In the same vein, Borges writes elsewhere about a map so large that it covers precisely, in 1:1 detail, everything it attempts to represent, so that it lays like a gigantic carpet over the land.

Gargantua (1534), a novel by Francois Rabelais. This novel by French writer Rabelais satirizes monasteries as places of leisure rather than spirituality.

Works in Critical Context

Despite Chesterton’s lasting popularity, critics generally agree that between his wide spectrum of subjects, his self- proclaimed role as a ‘‘mere journalist,’’ and his tendency toward irreverence, Chesterton is a ‘‘master who left no masterpiece.’’

Something of a Poet, but Perhaps Not Much. W. H. Auden argued that Chesterton was by natural gift a comic poet and that none of his serious poems is as good as his comic verse. ‘‘I cannot think of a single comic poem by Chesterton,” Auden wrote, ‘‘that is not a triumphant success.’’ Auden particularly praised Greybeards at Play, writing, ‘‘I have no hesitation in saying that it contains some of the best pure nonsense verse in English, and the author’s illustrations are equally good.’’

Auden notwithstanding, Chesterton’s reputation as a poet, which never rose particularly high during his lifetime, declined still further after his death. The conventional view of him as a poet has been that he wrote a few exquisite lyrics; helped popularize, through his satirical ballads, an effective kind of comic verse; and in his most important narrative poem, The Ballad of the White Horse, wrote an imperfect but partly successful English epic poem. The revival of critical interest in Chesterton during recent years has also made it possible to view his verse in a new light, revealing the close connection between his poetry and his everyday journalism.

The Father Brown Mysteries Father Brown remains, in the minds of most readers, Chesterton’s greatest creation, although his other contributions to the art of mystery writing are also recognized. ‘‘If Chesterton had not created Father Brown,’’ scholar Thomas Leitch declares, ‘‘his detective fiction would rarely be read today, but his place in the historical development of the genre would still be secure.’’ ‘‘Long before he published his last Father Brown stories,’’ Leitch continues, ‘‘Chesterton was widely regarded as the father of the modern English detective story. When Anthony Berkeley founded the Detection Club in 1928, it was Chesterton, not [Sherlock Holmes creator Arthur] Conan Doyle, who became its first president and served in this capacity until his death.’’ In addition, Leitch asserts, Chesterton ‘‘was the first habitual writer of detective stories ... to insist on the conceptual unity of the form, a criterion he expounded at length in several essays on the subject.’’ Under the influence of Chesterton’s Father Brown, the mystery story became less a portrait of the detective’s personality, and more a puzzle that the detective and the reader could both solve. ‘‘Chesterton’s determination to provide his audience with all the clues available to his detectives,’’ observes Leitch, ‘‘has been so widely imitated as to become the defining characteristic of the formal or golden age period (roughly 1920-1940) in detective fiction.... Modern readers, for whom the term whodunit has become synonymous with detective story, forget that the concealment of the criminal’s identity as the central mystery of the story is a relatively modern convention.’’ Chesterton was, however, much more than ‘‘merely’’ a mystery writers. As American Chesteron Society president Dale Ahlquist notes, ‘‘Chesterton wrote about everything.’’

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Ch'ien's famous contemporaries include:

Alaric (370-410): King of the Visigoths who sacked Rome in 410.

Theodosius I (347-395): The last emperor of both the Eastern and Western Roman Empires, he made Christianity the official state religion.

Attila the Hun (406-453): Infamous leader of the Hun horde and enemy of the late Roman Empire.

Responses to Literature

1. Much of Chesterton’s work was either implicitly or explicitly political. ‘‘A Song of Strange Drinks’’ is one example of personal politics inspiring what appears to be a work of silliness. Examine any of his light verse for political statement. Do you think the underlying messages in Chesterton’s light verse diminish or strengthen its importance as poetry? Why?

2. Chesterton has been called ‘‘the master who left no masterpiece.’’ Does the lack of a ‘‘masterpiece’’ detract from his stature as a writer? Should it? Why or why not?

3. Chesteron often employed the literary device of paradox in his work. What is paradox and how is it used in Chesterton’s work?

4. The Father Brown character is Chesterton’s most beloved creation. In what ways is he similar to and different from his near contemporary, Sherlock Holmes?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Ahlquist, Dale. Common Sense 101: Lessons from G. K. Chesterton. Fort Collins, CO: Ignatius Press, 2006.

Barker, Dudley. G. K. Chesterton: A Biography. London: Constable, 1973.

Clipper, Lawrence J. G. K. Chesterton. New York.: Twayne, 1974.

Coren, Michael. Gilbert: the Main Who Was G. K. Chesterton. New York: Paragon House, 1990.

Tolkien, J. R. R. Tree and Leaf. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, 1965.

Wills, Garry. Chesterton: Man and Mask. New York: Sheed & Ward, 1952.

Periodicals

Eliot, T. S. Obituary for Chesterton in Tablet, 20 (June 1936).

White, Gertrude M. ‘‘Different Worlds in Verse.’’ Chesterton Review, 4 (Spring-Summer 1978).

Web sites

The American Chesterton Society website. Retrieved March 25, 2008, from http://www.chesterton.org/.