World Literature

Agatha Christie

BORN: 1890, Torquay, England

DIED: 1976, Wallingford, England

NATIONALITY: British

GENRE: Fiction, Drama

MAJOR WORKS:

The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (1926)

Murder on the Orient Express (1934)

The Mousetrap (1952)

Witness for the Prosecution (1953)

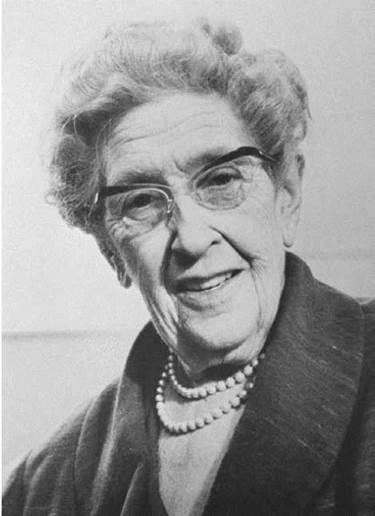

Agatha Christie. Christie, Agatha, photograph. The Library of Congress.

Overview

Agatha Christie is the most commercially successful woman writer of all time and probably the most widely read author of the twentieth century. A master of the murder mystery, her dozens of novels, stories, and plays have been translated into more than one hundred languages and have sold a phenomenal two billion copies—a record topped only by the Bible and the works of William Shakespeare. Her drama The Mousetrap opened on the London stage in 1952 and has yet to close; it is the longest-running play in theater history. Her ingenious plots, usually involving a mysterious death among a group of upper-middle-class British characters, invariably stumped crime buffs and largely defined the popular genre of the whodunit.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

Christie was born by the name of Agatha Mary Clarissa Miller on September 13, 1890, in the English seaside resort of Torquay, in Devon. She was the youngest of three children of Frederick Alvah Miller, an American from New York, and Clarissa Boehmer Miller. Her father died when she was a child, and until she was sixteen she was educated at home by her mother. She became an avid reader as a child, enjoying mysteries and often improvising them with her sister, Madge. She attended finishing school in Paris and initially considered a musical career.

Begins Career on a Dare. In 1912, Agatha Miller became engaged to Archibald Christie, a colonel in the Royal Air Corps; they were married on Christmas Eve, 1914. The couple was separated for most of the war years. Agatha Christie continued to live at Ashfield, her family’s Victorian villa in Torquay. She volunteered as a nurse and worked as a pharmaceutical dispenser in local hospitals. Her knowledge of poisons, evident in many of her mysteries, developed through these experiences. After the war, her husband went into business in London, while Christie remained at home with their daughter, Rosalind, born in 1919.

Christie wrote her first novel after her sister challenged her to try her hand at writing a mystery story. The result, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, was published in 1920. Like many of her subsequent classics, it features the detective Hercule Poirot, a former member of the Belgian police force. Although this maiden effort only sold some two thousand copies, the publication encouraged her to continue writing mysteries. Throughout the 1920s she wrote them steadily, building a loyal following among mystery aficionados for her unfailingly clever plots.

With her eighth book, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (1926), Christie gained notoriety, and her deceptive plotting caught the attention of the general reading public. The sheer audacity of the novel’s resolution—in which the murderer is ultimately revealed to be the narrator of the story, a character traditionally above suspicion in mystery novels— prompted a heated debate among mystery devotees. Christie’s violation of the crime genre’s conventions outraged some readers, but delighted many more. From that point, her reputation was established. For the next half-century, she was rarely absent from the best-seller lists.

Divorce and Remarriage. Christie’s personal life had become troubled, however. Shortly after her mother’s death, her husband asked for a divorce so that he could marry another woman. These emotional blows brought on a nervous breakdown. In December 1926 she disappeared for ten days, attracting great publicity. After this incident, Christie shunned the public eye for the rest of her life. Her divorce was finalized in 1928.

Two years after her divorce, however, while traveling on the Orient Express to see the excavations at Ur in Turkey, she met archaeologist Max Mallowan, whom she married the same year. During the 1930s, the couple divided their time between their several homes in England and many archaeological expeditions in the Middle East. Christie acted as her husband’s assistant on these digs, but she never stopped writing during her travels. This period provided Christie with experience of other cultures and a valuable distance from her own British one. She set several of her best-known works, including Murder on the Orient Express (1934) and Death on the Nile (1937), in exotic locales. Many of her other novels and plays are set in the British countryside, where corruption and crime lurk beneath the placid surface of middle-class life.

Poirot and Miss Marple. Christie was most famous for the literary creation of Hercule Poirot, one of detective fiction’s most famous sleuths. In his black jacket, striped trousers, and bow tie, the diminutive Belgian appeared in thirty-three novels and more than fifty short stories. Poirot regularly referred to the ‘‘little grey cells’’ of his brain; he relied primarily on reason in solving crimes, shunning the more physical and laborious tactics of A. Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes and other investigators. Christie grew distinctly sour on the pompous Poirot over the years—an occupational hazard for authors in the detective genre— yet she continued to crank out Poirot mysteries to meet the demands of her readers. She did, however, eliminate him from the stage versions of several of her stories, believing that Poirot was a more effective character in print.

In the novel The Murder at the Vicarage (1930), Christie introduced her other well-known detective: Miss Jane Marple, a genteel, elderly spinster who resides in a rural English village. Miss Marple is in many ways the antithesis of Poirot. Miss Marple works largely by intuition to solve crimes, often finding clues in village gossip. One of her most effective traits is her shrewd skepticism, which prevents her from taking anyone she meets at face value.

World War II brought about a major change in Christie’s life. Her husband served as an intelligence liaison officer in North Africa while Christie remained in London, working again as a volunteer dispenser. In her off hours, she was busy writing.

During the war years, Christie published ten novels and adapted two of her earlier works for the theater. Two of her wartime manuscripts were not published until decades later; these were the final Poirot and Miss Marple mysteries. Their author secreted them in a vault, to be published after her death.

Stage Triumphs. Christie’s work for the theater has proved as enduringly popular as her fiction and as full of cleverly constructed plots and surprise endings. Most of her plays are adaptations of her own stories or novels. One such work, originally titled Ten Little Niggers and subsequently retitled Ten Little Indians (1943), uses a children’s nursery rhyme to build suspense. Ten strangers assemble for a holiday on a small island, where, one by one, they are murdered. The combination of terror and orderly predictability creates a memorable theatrical mechanism.

The success of her early plays pales before the phenomenon of The Mousetrap (1952), which is now in its sixth decade of uninterrupted performances on the London stage. Despite the success of the work, Christie received no royalties for it. She gave the rights to her nine-year-old grandson when the play first opened; the grandson, it is estimated, has since earned well over fifteen million pounds Sterling from his grandmother’s gift. The year after The Mousetrap opened, Christie scored another smash with Witness for the Prosecution (1953).

Christie’s powers gradually declined in the decades after World War II, but she retained her towering popularity and reputation as the ‘‘Queen of Crime.’’ In 1971, she was made a Dame of the British Empire. Her last formal appearance was in 1974, at the opening of the film version of Murder on the Orient Express. As her health failed, her publishers persuaded her to release the final Poirot and Marple mysteries. Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case (1975) takes the detective back to Styles Court, the location of Christie’s first mystery. Poirot’s pursuit of an elusive killer leads to his inadvertent suicide. The death of Poirot caused a sensation, making the papers even in the People’s Republic of China, and spurring the New York Times to publish, for the first time, an obituary for a fictional character. Christie herself died the following year.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Christie's famous contemporaries include:

Virginia Woolf (1882-1941): British novelist and essayist, author of To the Lighthouse and A Room of One's Own.

Raymond Chandler (1888-1959): American crime novelist, creator of the private detective Philip Marlowe.

James N. Cain (1892-1977): American novelist, master of ''hard-boiled'' detective fiction; author of The Postman Always Rings Twice.

Dorothy L. Sayers (1893-1957): British novelist and dramatist, creator of the amateur detective Lord Peter Wimsey.

Alfred Hitchcock (1899-1980): Popular British filmmaker and producer, the ''master of suspense.''

Cecil Day-Lewis (1904-1972): Irish poet, author of mystery novels under the pseudonym Nicholas Blake.

Works in Literary Context

Agatha Christie enjoyed a wide selection of literature in her youth. The novelist Eden Philpotts, a neighbor, visited frequently and became a mentor to the home- schooled child. The Sherlock Holmes mysteries by A. Conan Doyle were a mainstay of her teenage years. Christie followed Doyle’s formula to some extent early on; for example, in her first mysteries, she gave Poirot a Watson- like sidekick, Captain Hastings. Other literary influences upon Christie were Edgar Allan Poe, G. K. Chesterton (who wrote the Father Brown detective stories), and the American detective novelist Anna Katherine Green.

Mystery Puzzles. Gamesmanship and subtle deception were the secrets of Christie’s success. The best of her novels are intricate puzzles, presented in such a way as to misdirect the reader’s attention away from the most important clues. The solution of the puzzle is invariably startling, although entirely logical and consistent with the rest of the story. Like a magician’s sleight of hand, a Christie mystery dispenses red herrings, ambiguities, shadings, and other subterfuges that keep the attentive reader baffled, until the story culminates in a satisfying surprise. In works such as Ten Little Indians and The A. B. C. Murders (1936), Christie uses nursery rhymes and other children’s games, uncovering their more sinister implications.

Straightforward Style. As befits this most commercial of novelists, her writing style was supremely unpretentious. She told stories in a straightforward manner, rarely injecting any thoughts or feelings of her own. She usually sketched her characters with the lightest of touches so that readers from any country could flesh them out to fit their own backgrounds. Her novels are frequently set in the English countryside, and usually focus on a group of upper-middle-class British characters and the detective who reveals the perpetrator at a final gathering of the suspects. One common theme that emerges from this genre formula is a concern with appearances, such as the respectable facade of parochial life, and the corruption and criminality that surface appearances conceal.

The Detective. Another important factor in Christie’s popularity is surely her ability to create charming and enduring detective characters. Both of her primary sleuths, Hercule Poirot and Jane Marple, gain reader sympathy from the way they are underestimated by other characters. Poirot, with his small stature, Belgian background, and amusing pomposity, arouses derision and, occasionally, ethnic prejudice. Similarly, Christie plays on Miss Marple’s eccentricities, in addition to her age and gender, to manipulate the reader into trivializing her capabilities. When the detective defies expectations and solves the crime, the resolution is that much more delicious.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Agatha Christie was one of the most prominent practitioners of a very popular literary genre, the murder mystery. Below are some of the more memorable titles, and heroes, of the whodunit.

''The Murders in the Rue Morgue'' (1841), by Edgar Allan Poe. Often considered the first detective story, Poe's ''tale of ratiocination'' established some of the conventions of crime fiction.

The Maltese Falcon (1930), by Dashiell Hammett. A detective novel with a dizzying plot, made into a classic motion picture starring Humphrey Bogart as the morally ambiguous private eye Sam Spade.

Maigret at the Crossroads (1931), by Georges Simenon. Maigret, the pipe-smoking inspector, is the protagonist of seventy-five novels and one of the best-known characters in popular French literature.

L.A. Confidential (1990), by James Ellroy. Three Los Angeles police officers, investigating the same homicide case, slowly uncover their own precinct's connections to organized crime, in this suspense novel made into a celebrated film.

A Ticket to the Boneyard (1991), by Lawrence Block. The hero of this detective story, private investigator Matt Scudder, struggles with alcoholism while tracking down a psychotic criminal released from prison.

Works in Critical Context

Agatha Christie began writing at the start of what became known as the golden age of the detective story, when mysteries were attaining worldwide popularity. As she continued to turn out books, her name became in the public mind almost a shorthand expression for the genre as a whole. Her bankability made her a literary institution long before the end of her extended career; the success of her brand with the reading and theater-going public made critical appraisal of her work largely moot.

The Ackroyd Controversy. Christie first drew critical attention with The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, which created a sensation upon its publication in 1926. Christie’s choice to make the novel’s narrator the murderer inspired vitriolic criticism from some reviewers—the London News Chronicle called it a ‘‘tasteless and unforgivable let-down by a writer we had grown to admire.’’ Other critics heaped extravagant praise on Christie for pulling off this narrative coup. British mystery writer Dorothy L. Sayers, a rival of Christie’s, defended her in the controversy. Roger Ackroyd certainly helped establish Christie’s name among the reading public, and in retrospect, it is considered one of her finest works. The prominent literary critic Edmund Wilson later attacked the genre as a whole with his controversial 1945 article in the New Yorker, ‘‘Who Cares Who Killed Roger Ackroyd?’’ Apparently, many people did.

Such books as Murder on the Orient Express, The A. B. C. Murders, and Ten Little Indians have been especially singled out by critics as among Christie’s best work and indeed, among the finest examples of the mystery genre. The literature available on Christie’s life and work is extensive, from armchair companions on her fictional characters, through numerous biographies and autobiographies, to more recent academic studies. Christie’s body of work has been of particular interest to contemporary feminist theorists. Although her work is lacking in overt social commentary, her challenges to traditional constructions of class, race, gender, and age have led to a reconsideration of her popularity. Some detractors of her work point to her workmanlike style, the formulaic structure of her novels, and the stereotyped nature of some of her characters. There can be no doubt, however, that her ingenious and intricate narrative puzzles have brought enjoyment to millions of readers.

Responses to Literature

1. There have been many great detectives throughout literary times, yet Poirot stands out as being unique. How so? What features illustrate his uniqueness? How is he different from, say, Sherlock Holmes? What makes each of them classics in their own right?

2. Write a character study of Miss Marple. How does she meet, and/or subvert, conventional expectations of the detective hero?

3. Closely analyze the mechanics of plotting in one of Agatha Christie’s novels. What techniques does she use to mislead the reader?

4. What insights into the class structure of British society can you gain from reading Agatha Christie?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Bargainnier, Earl. The Gentle Art of Murder: The Detective Fiction of Agatha Christie. Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green University Popular Press, 1980.

Barnard, Robert. A Talent to Deceive: An Appreciation of Agatha Christie. New York: Dodd, Mead, 1980.

Haining, Peter. Agatha Christie: Murder in Four Acts: A Centenary Celebration of the ‘‘Queen of Crime’’ on Stage, Film, Radio and TV. London: Virgin, 1990.

Irons, Glenwood, ed. Feminism in Women’s Detective Fiction. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1995.

Keating, H. R. F., ed. Christie: First Lady of Crime. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1977.

Klein, Kathleen. The Woman Detective. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1995.

Light, Alison. Forever England: Femininity, Literature and Conservatism between the Wars. London: Routledge, 1991.

Munt, Sally. Murder by the Book? Feminism and the Crime Novel. London: Routledge, 1994.

Osborne, Charles. The Life and Crimes of Agatha Christie. London: Collins, 1982.

Ramsey, G. C. Agatha Christie, Mistress of Mystery. New York: Dodd, Mead, 1967.

Wynne, Nancy Blue. An Agatha Christie Chronology. New York: Ace, 1976.