World Literature

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

BORN: 1772, Ottery St. Mary, Devonshire, England

DIED: 1834, London, England

NATIONALITY: British

GENRE: Poetry, nonfiction, drama

MAJOR WORKS:

Lyrical Ballads (1798, rev. ed., 1800)

Christabel (1816)

Biographia Literaria; or, Biographical Sketches of My Literary Life and Opinions (1817)

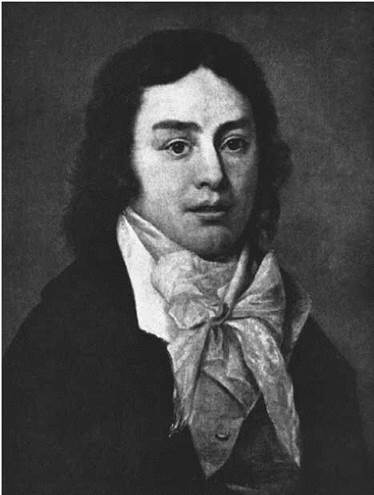

Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Coleridge, Samuel Taylor, photograph. The Library of Congress.

Overview

British author Samuel Taylor Coleridge was a poet, philosopher, and literary critic whose writings have been enormously influential in the development of modern thought. In his lifetime, Coleridge was renowned throughout Britain and Europe as one of the Lake Poets, a close-knit group of writers including William Wordsworth and Robert Southey. Today, Coleridge is considered the premier poet-critic of modern English tradition, distinguished for the scope and influence of his thinking about literature as much as for his innovative verse.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

Unfocused Youth. Coleridge was born on October 21, 1772, in the village of Ottery St. Mary, Devonshire, England, where he lived until the age of ten, when his father died. The boy was then sent to school at Christ’s Hospital in London. Later, he described his years there as desperately lonely; only the friendship of future author Charles Lamb, a fellow student, offered solace. From Christ’s Hospital, Coleridge went to Jesus College, Cambridge, where he earned a reputation as a promising young writer and brilliant conversationalist. He left in 1794 without completing his degree.

Coleridge then traveled to Oxford University, where he befriended Robert Southey. The two developed a plan for a ‘‘pantisocracy,’’ or egalitarian agricultural society, to be founded in Kentucky. By this time, the American colonies had completed their revolution, and the United States was in its infancy. Kentucky became a state in 1792. For a time, both Coleridge and Southey were absorbed by their revolutionary concepts and together composed a number of works, including a drama, The Fall of Robespierre (1794), based on their radical politics. Since their plan also required that each member be married, Coleridge, at Southey’s urging, wed Sara Fricker, the sister of Southey’s fiancee. Unfortunately, the match proved disastrous, and Coleridge’s unhappy marriage was a source of grief to him throughout his life. To compound Coleridge’s difficulties, Southey lost interest in the scheme, abandoning it in 1795.

Focused on Poetry Writing Career. Coleridge’s fortunes changed when in 1796 he met the poet William Wordsworth, with whom he had corresponded casually for several years. Their rapport was instantaneous, and the next year, Coleridge moved to Nether Stowey in the Lake District, where he and Wordsworth began their literary collaboration. Influenced by Wordsworth, whom he considered the finest poet since John Milton, Coleridge composed the bulk of his most admired work. Because he had no regular income, he was reluctantly planning to become a Unitarian minister when, in 1798, the prosperous china manufacturers Josiah and Thomas Wedgwood offered him a lifetime pension so that he could devote himself to writing.

Aided by this annuity, Coleridge entered a prolific period that lasted from 1798 to 1800, composing The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, Christabel, Frost at Midnight, and Kubla Khan. In 1798, Coleridge also collaborated with Wordsworth on Lyrical Ballads, a volume of poetry that they published anonymously. Coleridge’s contributions included The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, published in its original, rather archaic form. Most critics found the poem incomprehensible, including Southey, who termed it ‘‘a Dutch attempt at German sublimity.’’ The poem’s unpopularity impeded the volume’s success, and not until the twentieth century was Lyrical Ballads recognized as the first literary document of English Romanticism.

Focus on Criticism. As Coleridge was working with Wordsworth and publishing key poems, Great Britain was undergoing changes. While the British Empire had lost the thirteen American colonies, British settlement of Australia had increased, and New Zealand’s soon began. In 1800, the Act of Union of Great Britain and Ireland formally brought the United Kingdom into being. Following the publication of Lyrical Ballads, Coleridge traveled to what later became Germany, where nationalism was on the rise. He developed an interest in the philosophies of Immanuel Kant, Friedrich von Schelling, August Wilhelm, and Friedrich von Schlegel. Coleridge later introduced German aesthetic theory in England through his critical writings.

Upon his return in 1799, Coleridge settled in Keswick, near the Lake District. The move to Keswick marked the beginning of an era of chronic illness and personal misery for Coleridge. When his health suffered because of the damp climate, he took opium as a remedy and quickly became addicted. (Opium is a drug derived from poppy juice, which was commonly used for many ailments from fever to sleeplessness and pain management in Western medicine in this period. Many artists and writers of the Romanic period used opium.) His marriage, too, was failing; Coleridge had fallen in love with Wordsworth’s sister-in-law, Sara Hutchinson. He was separated from his wife, but since he did not condone divorce, he did not remarry.

End of Close Friendship with Wordsworth. In an effort to improve his health and morale, Coleridge traveled to Italy but returned to London more depressed than before. He began a series of lectures on poetry and Shakespeare, which helped establish his reputation as a critic, yet they were not entirely successful at the time because of his disorganized methods of presentation. Coleridge’s next undertaking, a periodical titled the Friend, which offered essays on morality, taste, and religion, failed due to financial difficulties. He continued to visit the Wordsworths, yet was morose and antisocial. When a mutual friend confided to him Wordsworth’s complaints about his behavior, an irate Coleridge, perhaps fueled in part by his jealousy of Wordsworth’s productivity and prosperity, repudiated their friendship. Although the two men were finally reconciled in 1812, they never again achieved their former intimacy.

Productive Years Late in Life. Coleridge’s last years were spent under the care of Dr. James Gilman, who helped him control his opium habit. Despite Coleridge’s continuing melancholy, he was able to dictate the Biographia Literaria; or, Biographical Sketches of My Literary Life and Opinions (1817) to his friend John Morgan. The Biographia Literaria contains what many critics consider Coleridge’s greatest critical writings. In this work, he developed aesthetic theories, which he had intended to be the introduction to a great philosophical opus that was never completed.

Coleridge published many other works during this period, including the unfinished poems Kubla Khan and Christabel, as well as a number of political and theological writings. This resurgence of productivity, coupled with his victory over his addiction, brought Coleridge renewed confidence. His newfound happiness was marred by failing health, however, and he died in 1834 of complications from his lifelong dependence on opium.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Coleridge's famous contemporaries include:

William Wordsworth (1770-1850): Coauthor with Coleridge of Lyrical Ballads, Wordsworth was one of the founding fathers of the Romantic movement.

Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821): French general and emperor, Napoleon's ambitions brought the French Revolution to a close and directly influenced the course of European and American history for more than a century to come.

Eli Whitney (1765-1825): American inventor remembered for inventing the cotton gin, a device that greatly increased the productivity of cotton farmers.

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827): German composer Beethoven was highly influential at the end of the Classical era of music. His compositions were popular with the new generation of Romantic artists.

George Walker (1772-1847): English Gothic novelist who wrote in the antireform style, his works were reactions against the work of writers William Godwin and Thomas Holcroft.

Works in Literary Context

Readers of Coleridge have always been confronted with a daunting problem in the sheer volume and incredible variety of his writings. His career as an intellectual figure spans several decades and encompasses major works in several different fields, including poetry, criticism, philosophy, and theology. Because of the richness and subtlety of his prose style, his startling and often profound insights, and his active, inquiring mind, Coleridge is now generally regarded as the most profound and significant prose writer of the English Romantic period.

Spiritual Symbolism. The poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner perhaps best incorporates both Coleridge’s imaginative use of verse and the intertwining of reality and fantasy. The tale of a seaman who kills an albatross, the poem presents a variety of religious and supernatural images to depict a moving spiritual journey of doubt, renewal, and eventual redemption. The symbolism contained in this work has sparked diverse interpretations, and several commentators consider it an allegorical record of Coleridge’s own spiritual pilgrimage. Critics also debate the nature of the Mariner’s salvation and question whether the poem possesses a moral.

Influence of German Romantic Philosophy. Coleridge’s analyses channeled the concepts of the German Romantic philosophers into England and helped establish the modern view of William Shakespeare as a master of depicting human character. The Biographia Literaria, the most famous of Coleridge’s critical writings, was inspired by his disdain for the eighteenth-century empiricists who relied on observation and experimentation to formulate their aesthetic theories. In this work, he turned to such German philosophers as Kant and Schelling for a more universal interpretation of art. From Schelling, Coleridge drew his “exaltation of art to a metaphysical role,’’ and his contention that art is analogous to nature is borrowed from Kant.

Definition of Imagination. Of the different sections in the Biographia Literaria, perhaps the most often studied is Coleridge’s definition of the imagination. He describes two kinds of imagination, the primary and the secondary: the primary is the agent of perception, which relays the details of experience, while the secondary interprets these details and creates from them. The concept of a dual imagination forms a seminal part of Coleridge’s theory of poetic unity, in which disparate elements are reconciled as a unified whole. According to Coleridge, the purpose of poetry was to provide pleasure ‘‘through the medium of beauty.’’

Shakespeare Criticism. Coleridge’s other great critical achievement is his work on Shakespeare. His Shakespearean criticism is among the most important in the English language, although it was never published in formal essays; instead, it has been recorded for posterity in the form of marginalia and transcribed reports from lectures. Informed by his admiration for and understanding of Shakespeare, Coleridge’s critical theory allowed for more in-depth analysis of the plays than did the writings of his eighteenth-century predecessors. His emphasis on individual psychology and characterization marked the inception of a new critical approach to Shakespeare, which had a profound influence on later studies.

Influence. As a major figure in the English Romantic movement, he is best known for three poems, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, Kubla Khan, and Christabel. Although the three poems were poorly received during Coleridge’s lifetime, they are now praised as classic examples of imaginative verse. The influence of Ancient Mariner rings clear in Shelley and Keats in the next generation, and in Tennyson, Browning, Rossetti, and Swinburne among their Victorian inheritors. In the title of W. H. Auden’s Look, Stranger! (1936), the echo of the Mariner’s exhortation, ‘‘Listen, Stranger!’’ from the text of 1798, shows how far Coleridge’s voice would carry.

Coleridge was also influential as a critic, especially with Biographia Literaria. His criticism, which examines the nature of poetic creation and stresses the relationship between emotion and intellect, helped free literary thought from the neoclassical strictures of eighteenth- century scholars.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Coleridge claimed Kubla Khan was inspired by an opium- induced dream. Here are some other works that were inspired by dreams, opium experiences, or flights of imagination:

Confessions of an English Opium Eater (1822), a memoir by Thomas de Quincey. Coleridge's friend and fellow opium addict wrote of his experiences with addiction.

The Castle of Otranto (1764), a novel by Horace Walpole. The first Gothic novel, this story set the genre's conventions, from crumbling castles to secret passageways to melodramatic revelations. A sensation upon its publication, it single-handedly launched a genre.

Compendium of Chronicles (1307), a literary work by Rashid al-Din. This fourteenth-century Iranian work of literature and history includes the detail that the inspiration for Kubla Khan's palace was given to the Mongolian ruler in a dream. The book was published in English for the first time twenty years after the final revision of Coleridge's masterpiece.

The Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1790-1793), a poem by William Blake. This poem explicitly explores the relationship between the conscious and the unconscious minds and the role of imagination as prophecy.

Works in Critical Context

Critical estimation of Coleridge’s works increased dramatically after his death, but relatively little was written on them until the twentieth century. Opinions of his work vary widely, yet few today deny the talent evident in The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, Kubla Khan, and Christabel.

The Coleridge phenomenon, as it might be called, has been recounted in every literary generation, usually with the emphasis on wonder rather than disappointment, though sometimes—among moralizing critics, never among poets—with a venom that recalls the disillusionment of his associates. Henry James’s story, ‘‘The Coxon Fund’’ (1895), based on table talk of the genius who became a nuisance, is indicative of both attitudes. The Coleridge phenomenon has distorted Coleridge’s real achievement, which was unique in scope and aspiration if all too human in its fits and starts.

Kubla Khan. For many years, critics considered Kubla Khan merely a novelty of limited meaning, but John Livingston Lowes’s 1927 study, The Road to Xanadu: A Study in the Ways of the Imagination, explored its imaginative complexity and the many literary sources that influenced it, including the works of Plato and Milton. Though Coleridge himself dismissed the poem as a ‘‘psychological experiment,’’ it is now considered a forerunner of the work of the Symbolists and Surrealists in its presentation of the Unconscious.

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Lyrical Ballads was deliberately experimental, as the authors insisted from the start, and Ancient Mariner pointed the way. The largely negative reviews that the book excited on publication concentrated on Ancient Mariner, in part because it was the most substantial poem in the collection, but also because of its self-consciously archaic diction and incredible plot. The poem was considered strange, and the character of the Mariner also caused confusion.

Despite the problems, the poem flourished on the basis of strong local effects—of its pictures of the ‘‘land of ice and snow’’ and of the ghastly ship in the doldrums, in association with a drumming ballad meter. Wordsworth frankly disliked it after the reviews came in, but Lamb led the way in appreciating its odd mix of romance and realism. Showing its influence, satires were also published in leading periodicals.

Responses to Literature

1. The Rime of the Ancient Mariner is a poem steeped in symbolism. Choose an aspect or character of the poem (such as the Albatross) and discuss its symbolic meanings.

2. Featured in Coleridge’s Kubla Khan, Xanadu has since entered the English language as another word for paradise or utopia. Describe your own personal Xanadu in a poem.

3. Like Kubla Khan, Percy Bysshe Shelley’s Ozymandias describes a fantastical ancient kingdom. Compare the two kingdoms and how they influence the tone of their respective poems.

4. In The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, the killing of an albatross represents a crime against nature. What crimes against nature might a modern person commit to bring about similar punishment as suffered by the Mariner?

5. How does the historical Kublai Khan compare with Coleridge’s dream-inflected vision of the Mongol leader?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Sources

Books

Armour, Richard W., and Raymond F. Howes, eds. Coleridge the Talker: A Series of Contemporary Descriptions and Comments. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1940.

Caskey, Jefferson D., and Melinda M. Stapper. Samuel Taylor Coleridge: A Selective Bibliography of Criticism, 1935-1977. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood, 1978.

Goodson, A. C. Verbal Imagination: Coleridge and the Language of Modern Criticism. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Gravil, Richard, Lucy Newlyn, and Nicholas Roe, eds. Coleridge’s Imagination. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985.

Magnuson, Paul. Coleridge and Wordsworth: A Lyrical Dialogue. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1988.

Roe, Nicolas. Wordsworth and Coleridge: The Radical Years. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

Weissman, Stephen M. His Brother’s Keeper: A Psychobiography of Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Madison, Conn.: International Universities Press, 1989.

Wylie, Ian. Young Coleridge and the Philosophers of Nature. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.