World Literature

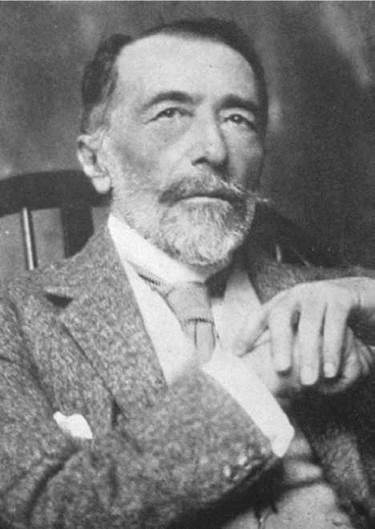

Joseph Conrad

BORN: 1857, Berdiczew, Podolia, Russia (now Poland)

DIED: 1924, Bishopsbourne, Kent, England

NATIONALITY: Polish

GENRE: Novels, short stories

MAJOR WORKS:

Heart of Darkness (1899)

Lord Jim (1900)

The Secret Sharer (1909)

Joseph Conrad. Conrad, Joseph, photograph. The Library of Congress.

Overview

Joseph Conrad is widely regarded as one of the foremost prose stylists of English literature—no small achievement for a man who did not learn English until he was twenty. A native of what is now Poland, Conrad was a naturalized British subject famous both for his minutely described adventure tales of life on the sea (he drew on his own maritime experience for these) and his darker examinations of European imperialism in action.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

Early Life in Exile. Conrad’s childhood was harsh. His parents were both members of families long identified with the movement for Polish independence from Russia. In 1862 Conrad’s father, himself a writer and translator, was exiled to Russia for his revolutionary activities, and his wife and child shared the exile. In 1865 Conrad’s mother died, and a year later he was entrusted to the care of his uncle Thaddeus Bobrowski.

In 1868 Conrad attended high school in Lemberg, Galicia; the following year he and his father moved to Cracow, where his father died. In early adolescence the future novelist began to dream of going to sea, and in 1873, while on vacation in western Europe, Conrad saw the sea for the first time. In the autumn of 1874 Conrad went to Marseilles, where he entered the French merchant-marine service. Conrad’s experiences at sea would figure prominently in his writing.

A Career on the Sea. For the next twenty years Conrad pursued a successful career as a ship’s officer. In 1877 he probably took part in the illegal shipment of arms from France to Spain in support of the pretender to the Spanish throne, Don Carlos. There is evidence that early in 1878 Conrad made an attempt at suicide, most likely because of a failed love affair. In June 1878 Conrad went to England for the first time. He worked as a seaman on English ships, and in 1880 he began his career as an officer in the British merchant service, rising from third mate to master. His voyages took him to Australia, India, Singapore, Java, Borneo, to those distant and exotic places which would provide the background for much of his fiction. In 1886 he was naturalized as a British subject. He received his first command in 1888.

Journey to the Congo. In 1890 he made a difficult journey to the Belgian Congo that inspired his great short novel Heart of Darkness. At the time, the Belgian Congo was a corporate ‘‘state’’ privately controlled by King Leopold II of Belgium—in effect, he owned the country. In pursuing personal profits from the natural resources of the Congo, most notably rubber, Leopold ruthlessly exploited the Congo natives, subjecting them to slavery, rape, mutilation, and mass murder. By 1900, an international uproar over the horrors in the Congo was erupting, partly thanks to the publication of Heart of Darkness.

First Writing Efforts. In the early 1890s Conrad had begun to think about writing fiction based on his experiences in the East, and in 1893 he discussed his work in progress, the novel Almayer’s Folly, with a passenger, the novelist John Galsworthy. (Galsworthy was the first of a number of English and American writers who befriended this middle-aged Polish seaman who had come so late to the profession of letters.) Almayer’s Folly was published in 1895, and its favorable critical reception encouraged Conrad to begin a new career as a writer. He married an Englishwoman, Jessie George in 1896, and two years later, just after the birth of Borys, the first of their two sons, they settled in Kent in the south of England, where Conrad lived for the rest of his life.

Financial Struggles. Though Conrad had achieved a positive critical reputation by the early 1900s, he lacked financial security. Forever in debt to friends and his agent, James Pinker, he and his family moved to Pent Farm in Kent in 1898, renting a brick cottage from a young writer named Hueffer, later known as Ford Madox Ford. While living in Kent, Conrad and Ford collaborated on two novels, The Inheritors and Romance, and Conrad came into contact with other writers nearby, including Stephen Crane, H. G. Wells, and Henry James, whom Conrad greatly revered. Other literary friends, including John Galsworthy and George Bernard Shaw, loaned him money and helped further his literary career by promoting his works to publishers and critics. The birth of a second son in 1906 made an already strained financial situation even worse. Ford and Conrad fell out over rent Conrad owed, and in 1907 the Conrad family moved to Bedfordshire, and from there in 1909 to Aldington, where they occupied four rooms over a butcher shop. By 1910, Conrad’s debt had grown to be more than $100,000 in late-twentieth-century values.

All the while, Conrad managed to keep writing. During these difficult years, he turned out some of his finest novels, including Nostromo, The Secret Agent, and Under Western Eyes, as well as his short-story masterpiece, ‘‘The Secret Sharer.’’ While the novels leave the sea behind for more political and social issues—a critique of materialism in Nostromo, an anarchist bombing in The Secret Agent, and the world of a double agent in Under Western Eyes—a love of the sea remained in Conrad’s blood. It was once again the setting for ‘‘The Secret Sharer.’’

Success and Security. With his 1913 novel, Chance, Conrad finally achieved not only celebrity but also financial security. He carried on a lively social life, increasing his circle to include French writer Andre Gide. Conrad, who had been such a roamer in his youth, traveled little in his later years, though he did visit the United States in late 1922 at the request of his American publisher, Doubleday. Despite claiming he was never a man for awards—Conrad refused knighthood in May 1924—he did harbor a desire for a Nobel Prize. He never received one. On August 3, 1924, Conrad died of a heart attack, leaving unfinished the novel Suspense.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Conrad's famous contemporaries include:

Sigmund Freud (1856-1939): This Austrian neurologist founded psychoanalysis.

Stephen Crane (1871-1900): Like Conrad, this American writer (author of The Red Badge of Courage, 1895) was a master stylist who led an adventurous life.

F. Scott Fitzgerald (1896-1940): An American novelist, Fitzgerald is best known for his critique of high society in the 1920s, as exemplified in The Great Gatsby (1925).

Franz Ferdinand (1863-1914): The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, set in motion a series of events that ultimately led to World War I.

Samuel Clemens (also known as Mark Twain) (18351910): This American novelist, like Conrad, received much acclaim for a novel about life on a river.

Works in Literary Context

Conrad was, according to Kingsley Widmer in the Concise Dictionary of British Literary Biography, ‘‘a major figure in the transition from Victorian fiction to the more perplexed forms and values of twentieth-century literature... .’’ He was simultaneously one of the last Victorian writers and one of the first modernist writers. Along with writers like Mark Twain, Conrad was able to incorporate traditional story forms—such as travelogues or journey stories—into novels with a more contemporary sensibility.

Personal Quests. Heart of Darkness is not so much about the enigmatic character Kurtz as it is about Marlow and his discovery of good and evil in each individual; his quest is not so much for Kurtz, but for truth within himself. As such, the novella has been compared to Virgil’s Aeneid as well as Dante’s Inferno and Goethe’s Faust.

Reading Heart of Darkness as a journey story in which a man comes to understand his own soul will help one understand why the filmmaker Francis Ford Coppola felt the novella would be a good model for his representation of the Vietnam war in Apocalypse Now. In Coppola’s retelling of Heart of Darkness, an American soldier in Vietnam must face great suffering and is forced to understand the devastation wrought by the war of which he is part.

The Distanced Narrator. With the invention of his character Marlow, Conrad broke new ground in literary technique, establishing the distancing effect of reported narration, a narrative frame in which the story is told at one or more removes from the actual action. To achieve this effect, Conrad employs a character within the story who relates the action after the fact. Such a technique helped Conrad avoid what would otherwise be painfully intense subjectivity.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

It is difficult to read Conrad without seeing the influences of the sea on his writing and thinking. Indeed, the isolation an individual faces on a ship and pitting oneself against both nature and others on the ship, has been a common theme in literature, at least as old as Homer's Odyssey. Here are some more works that analyze the effects of the sea on humankind:

Moby-Dick (1851), by Herman Melville. This novel retells the story of Captain Ahab, who seeks Moby-Dick, a whale that has destroyed one of Ahab's ships.

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1870), by Jules Verne. The mysterious Captain Nemo and his famous vessel the Nautilus take a fantastic journey through the world's oceans in the science-fiction classic.

Kon-Tiki (1950), by Thor Heyerdahl. Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl, intrigued by Polynesian folklore, sets off across the Pacific Ocean in a raft in 1947. This book tells the true story of his adventure.

The Old Man and the Sea (1951), by Ernest Hemingway.

In this piece, an aging Cuban fisherman struggles to catch an exceptionally large marlin.

Master and Commander (2003), a film directed by Peter Weir. This film, based on the novels of Patrick O'Brian, recounts the battles between two ships in the South Atlantic and South Pacific Oceans.

Works in Critical Context

Conrad’s work met with immediate success and praise. Not only is his skill noteworthy, but the fact that Conrad wrote in English, which was not his native language, made his use of delicate and original phrasings that much more astounding. As time progressed, however, Conrad picked up his fair share of negative critics, including novelist Chinua Achebe, who felt that Conrad’s portrayal of the native Africans in Heart of Darkness is racist. Achebe noted that not one of the natives is portrayed as a fully fleshed out character, thereby, in Achebe’s estimation, reducing the characters to a subhuman level. Additionally, Achebe cited Conrad’s use of white symbols to represent that which is good and black symbols to represent that which is bad as further evidence for his intrinsic racism. Lord Jim is another of Conrad’s books that has been deemed racist because of his associating people of color with the darker forces of chaos. However, many critics contend that Conrad was no more susceptible to racist thought than others of his time and was in fact ahead of his time in calling attention to the ravages caused by colonialism.

Heart of Darkness. Contemporary reviewers praised Conrad for his insight and vivid use of language. ‘‘The art of Mr. Conrad is exquisite and very subtle,’’ observed a reviewer for the Athenaeum, who went on to note that Heart of Darkness cannot be read carelessly ‘‘as evening newspapers and railway novels are perused—with one mental eye closed and the other roving. Mr Conrad himself spares no pains, and from his readers he demands thoughtful attention.’’ A reviewer in the Times Literary Supplement considered the concluding scene of the novella ‘‘crisp and brief enough for Flaubert.’’ Conrad’s novella quickly entered the canon, eliciting response from critics on both sides of the Atlantic. In an essay originally published in 1917, the American critic H.L. Mencken focused on the character of Kurtz, concluding that he was ‘‘at once the most abominable of rogues and the most fantastic of dreamers.’’

As Lillian Feder noted in Nineteenth-Century Fiction, the novella has ‘‘three levels of meaning: on one level it is the story of man’s adventures; on another, of his discovery of certain political and social injustices; and on a third, it is a study of his initiation into the mysteries of his own mind.’’ Critics still debate to what degree Marlow finds his evil double in Kurtz and how far, in fact, he identifies with him. Conrad would employ this theme of doubling in later works also, most notably in Lord Jim and ‘‘The Secret Sharer.’’

Other critics have remarked about the psychological aspects of the work as well as its tone. The American novelist and critic, Albert J. Guerard, in his Conrad the Novelist, noted not only Conrad’s “dramatized psychological intuitions,’’ but also the “impressionist method’’ and the ‘‘random movement of the nightmare,’’ which works on the “controlled level of a poem.’’ Guerard pointed to the contrasting use of dark and light by Conrad as a conscious symbol, and to his vegetative images, which grow to menacing proportions. ‘‘Heart of Darkness... remains one of the great dark meditations in literature,’’ Guerard wrote, ‘‘and one of the purest expressions of a melancholy temperament.’’ As Frederick R. Karl noted in his A Reader’s Guide to Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness is one of the world’s greatest novellas: ‘‘It asks troublesome questions, disturbs preconceptions, forces curious confrontations, and possibly changes us.’’ Conrad’s novella is where, according to Karl, ‘‘the nineteenth century becomes the twentieth.’’

Lord Jim. From its earliest reviews, Lord Jim has been considered perhaps Conrad’s greatest novel and has been favorably compared to the best that Western literature has to offer. A reviewer in the Spectator noted that Lord Jim was ‘‘the most original, remarkable, and engrossing novel of a season by no means unfruitful of excellent fiction,’’ while an Academy critic pronounced that ‘‘Lord Jim is a searching study—prosecuted with patience and understanding—of a cowardice of a man who was not a coward.’’ A Bookman contributor acknowledged that the novel ‘‘may find various criticism.’’ However, the anonymous reviewer concluded that, ‘‘Judged as a document, it must be acknowledged a masterpiece.’’

Political and social issues aside, Lord Jim is a fascinating case study of a romantic idealist. Some scholars take a more biographical approach to the novel. From this perspective, Jim is a representative of Conrad himself who jumped the Polish ship of state at its most difficult moment to settle in England. The Polish Nobel poet, Czeslaw Milosz, in Atlantic Monthly, pointed out that the name of Jim’s ship, Patna, is intended to resonate with the Latin patria or ‘‘fatherland.’’ Other, more psychoanalytically minded reviewers note the fact that Lord Jim was published the same year as Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams, both books heralding a new century of unconscious forces at work. Still others, including Ira Sadoff in the Dalhousie Review, credit Jim with being a protoexistential hero. ‘‘Camus’s greatest novel, The Stranger, written forty-two years after Lord Jim, is the epitome of the existential novel,’’ Sadoff noted. ‘‘Yet Meursault, the hero of the book, is not so different from Jim.’’ But beyond all these interpretations is the simple fact that the book presents a great yarn. As G. S. Fraser commented in Critical Quarterly, ‘‘It is, in fact, part of the interest and range of Conrad that he appeals not only to the sort of reader who enjoys, say George Eliot or Henry James but to the sort who enjoys Robert Louis Stevenson, Rider Haggard, or Conan Doyle.’’

Responses to Literature

1. Chinua Achebe criticized Conrad’s portrayal of the native Africans in Heart of Darkness as being racist. Read several passages from Achebe’s novel Things Fall Apart, taking note of the ways Achebe characterizes Africans. Based on your readings of both authors’ works, do you think Conrad’s novel is, either overtly or subtly, a racist text? Why or why not?

2. After reading Heart of Darkness, watch Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now. Compose an interview with Coppola in which he answers a reporter’s questions about the conception and making of the movie.

3. Read Lord Jim. In your opinion, is Jim portrayed as a courageous man? Why or why not?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Gordan, John. Joseph Conrad: The Making of a Novelist. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1940.

Guerard, Albert J. Conrad the Novelist. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1966.

Howe, Irving. Politics and the Novel. New York: Horizon, 1957.

Kimbrough, Robert, ed. Heart of Darkness: Norton Critical Edition. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1966.

Najder, Zdzislaw. Joseph Conrad: A Chronicle. Piscataway, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1983.

Page, Norman. A Conrad Companion. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1966.

Said, Edward. Joseph Conrad and the Fiction of Autobiography. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1966.

Sherry, Norman. Conrad: The Critical Heritage. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1973.