World Literature

Nuruddin Farah

BORN: 1945, Baidoa, Somalia

NATIONALITY: Somali

GENRE: Fiction, drama

MAJOR WORKS:

From a Crooked Rib (1970)

Sweet and Sour Milk (1979)

Sardines (1981)

Maps (1986)

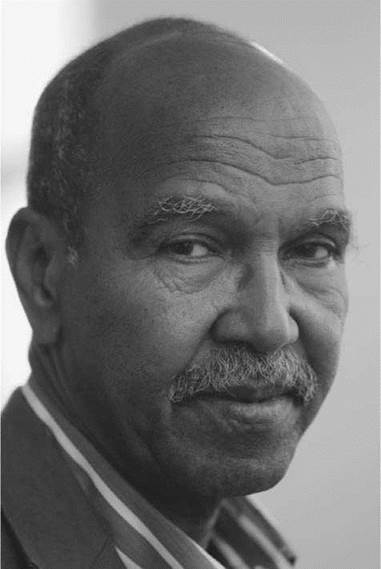

Nuruddin Farah. Ulf Andersen / Getty Images

Overview

An important figure in contemporary African literature whose fiction is informed by his country’s turbulent history, Farah combines native legends, myths, and Islamic doctrines with a journalistic objectivity to comment on his country’s present autocratic government. His criticism of traditional Somali society—in particular, the plight of women and the patriarchal family structure—has made him an ‘‘enemy of the state,’’ and he has lived in voluntary exile in England and Nigeria. Kirsten Holst Petersen described Farah’s ‘‘thankless task’’ of writing about the oppressed: ‘‘Pushed by his own sympathy and sensitivity, but not pushed too far, anchored to a modified Western bourgeois ideology, he battles valiantly, not for causes, but for individual freedom, for a slightly larger space round each person, to be filled as he or she chooses.’’

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

Early Life in a Tradition of Rich Oral Culture. Born in 1945 in Baidoa to Hassan Farah (a merchant) and Aleeli Faduma Farah (a poet), Nuruddin Farah was educated at first in the Ogaden, a Somali-populated area now in Ethiopia. His first languages as a child were Somali, Amharic, and Arabic, followed by Italian and English. From these early years one can see two important features that were to dominate his writing life. First, he was brought up in a tradition with a rich oral culture, in which poetry is a craft that takes years to master. Poetry enters political debates in a sophisticated manner, epic or satirical but also oblique and allusive, and plays an important social function. Some of Farah’s relatives, including his mother, are known masters of the genre. Second, the history of colonization and borders gave him early access to a wide range of cultures: his travels and readings made him a cosmopolitan writer, a world nomad who was to write from a distance about Somalia, ‘‘my country in my mind,’’ as he once called it.

In 1965 his novella Why Die So Soon? brought him to public attention in his country and into contact with the Canadian writer Margaret Laurence, then in Somalia. While a student at the University of Chandigarh in India (1966-1970) he wrote—in two months—From a Crooked Rib (1970), a novel that has maintained its popularity for the past thirty-eight years.

Uncertain Future and Coup in Somalia. In 1969 a coup gave power to the military regime of Siad Barre, replacing the democratic government that came to power in 1960 when Somalia gained its independence from Italy. In 1970 Farah went back to Somalia with his Indian wife, Chitra Muliyil Farah, and their son, Koschin (born in 1969). Farah then taught at a secondary school and finished his second novel, A Naked Needle. The publisher accepted it but agreed to hold it, until 1976, due to political uncertainty in Somalia. It describes the debates among the elite in the capital, the ‘‘privile- gentzia’’—the privileged—and the tentative hopes in the new ‘‘revolution.’’ Later Farah rejected this early book as irrelevant and refused to have it reprinted: ‘‘It was not the answer to the tremendous challenge the tyrannical regime posed,’’ he says in ‘‘Why I Write’’ (1988).

Censorship and Exile. In 1972 the Somali language was given an official transcription and dictionary; what was spoken by the whole nation could become a national literary language. It was for Farah the long-awaited opportunity to write fiction in his mother tongue and thereby speak directly to his people. In 1973 he started the serialization of a novel titled ‘‘Tolow Waa Talee Ma ...!’’ in Somali News, but the series was interrupted by censorship. Farah, then on a trip to the Soviet Union, was advised not to run any more risks. Thus he began a long exile from his country.

Extending Political Themes in Fiction. His visit to the Soviet Union extended to a trip through Hungary, Egypt, and Greece in the days of the Siad Barre military regime. From this contact with various types of political power came his first major novel, Sweet and Sour Milk (1979). It had to be written in English, since Farah could no longer be published at home. But this imposed language, implicitly creating an international readership, extended the scope of his fictional exploration of political themes. With this novel Farah started a trilogy he calls ‘‘Variations on the Theme of an African Dictatorship,’’ which has much relevance inside and outside Africa.

His next novel, Maps (1986), began another trilogy known as the ‘‘Blood in the Sun’’ trilogy. These works were set amid the real-life Ogaden War, a territorial dispute fought between Somalia and Ethiopia in the 1970s. In 1996, Farah once again returned to his home country, which was then under the weak control of the Transitional Federal Government (TFG). This mirrors the events in his 2007 novel Knots, in which a Somali woman who has lived most of her life in Canada returns to her native country to discover the devastation caused by the local warlords. Farah also wrote Yesterday, Tomorrow: Voices from the Somali Diaspora (2000), a nonfiction book that chronicles the lives of Somalis forced to flee from the country after the collapse of the government in 1991. In 1998 Farah was awarded the prestigious Neu- stadt International Prize for Literature and is regarded by many as one of Africa’s most significant literary figures of the twentieth century.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Farah's famous contemporaries include:

Chinua Achebe (1930-): Nigerian author of Things Fall Apart (1958), the most widely successful African novel ever published.

V. S. Naipaul (1934-): Trinidad-born author and Nobel Prize winner whose 1979 novel, A Bend in the River, concerned a Muslim living in an African country recently granted its independence.

Gloria Steinem (1934-): Outspoken American feminist, writer, and cofounder of Ms. magazine.

Benazir Bhutto (1953-2007): Extremely popular Pakistani politician who went into a self-imposed exile in 1998. In 2007, she returned to Pakistan to run for office but was assassinated on December 27, 2007, within weeks of the upcoming election.

Siad Barre (1919-1995): This army commander came to power after the assassination of President Abdirashid Ali Shermarke and the military coup of 1969; after replacing the democratic government with his military regime, Barre held power as the Head of State of Somalia until 1991.

Works in Literary Context

Nuruddin Farah’s novels are an important contribution to African literature. He writes about his country, Somalia, but the interest is more than regional: The books present the theme of individual freedom in the face of arbitrary power in a way that is relevant outside Africa as well, and they do so with an intellectual and poetic control that makes him one of the most stimulating prose writers in Africa today. Influenced by the work of authors in his extended family, the guiding topic for the majority of Farah’s work is the plight of women in Somalia. Nuruddin’s novels were not well-received by the military regime in Somalia, however, he did receive mild praise from critics abroad.

Linking Freedom with Feminism. In the slim novel From a Crooked Rib, a young Somali woman, Ebla, leaves her nomad community to avoid an arranged marriage, and in her quest for independence she finally finds a kind of stability in the capital, Mogadishu, living with two men of her choice. The journey to freedom can be read as an allegory of the birth of Somalia as a new nation. But the attraction of the book lies in the sensitive portrayal of a young peasant woman, illiterate but not naive, aware of her low status in society but always clear-eyed and resourceful. It came as a surprise to readers to realize how well the young writer, male and Muslim, could represent a woman’s perception of herself, her body, and the world.

Sardines (1981) is another of Farah’s strikingly feminist novels. The story focuses on the world of women hemmed in together in their houses, women who are like children hiding in closets when they play the game ‘‘sardines.’’ Medina, a journalist, has decided that her daughter, Ubax, aged eight, is not going to go through the ritual clitoral excision and infibulation performed on all Somali women according to custom. Medina is pitted against her ineffectual husband and the power of her mother and mother-in-law. Although ideological debates play an important part in the story, the main weight of the meaning is again carried by a dense metaphorical network: natural images—fire, water, and birds—show how the balance in the fertility cycles is broken by the socially enforced clitoral circumcision, seen by Farah as a deliberate maiming of women. Again the issue is not merely feminism; it is connected with overall political oppression: ‘‘Like all good Somali poets,’’ Farah told Julie Kitchener, ‘‘I used women as a symbol for Somalia. Because when the women are free, then and only then can we talk about a free Somalia.’’ In Sardines Farah touches a taboo subject as a warning to his compatriots, but also to all nations where, according to him, the subjection of women paves the way for the establishment of tyranny.

Advocating Human Rights. Farah is generally acknowledged, along with Sembene Ousmane and Ayi Kwei Armah, whose female characters also possess the same vision as Farah’s women, as one of the African writers who has done the greatest justice in championing human rights through his work. His influence extends beyond the world of literature to include political and cultural realms, particularly with regard to gender inequality.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Farah's novels are notable for their concern with the problems experienced by women in his native Somalia. Indeed, Farah has been credited with writing the first feminist novel to come out of Africa. However, feminism in literature dates back at least to the late eighteenth century, and has been produced in many cultures around the world. Here are a few more prominent feminist texts that argue that women deserve more freedom than society then allowed them:

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), a treatise by Mary Wollstonecraft. This work, written by the mother of Mary Shelley—the author of Frankenstein—is one of the first to present an argument for women's rights in general, and the right to an education in particular.

The Feminine Mystique (1963), a nonfiction work by Betty Friedan. In this work, Friedan discusses the stifling nature of the role to which women were relegated at that time in America: the role of housewife, a position that she finds "terrifying" because of the loneliness the housewife must feel to be all day cut off from interactions with other adults.

The Subjection of Women (1869), an essay by John Stuart Mill. Arguing against the patriarchal system in which he lived and in favor of equality between the sexes, John Stuart Mill became one of the first major authors to support the burgeoning feminist movement.

A Room of One's Own (1929), an essay by Virginia Woolf. One of the arguments made against the equality of men and women in the artistic sphere during Woolf's lifetime was that women had not proven themselves capable of producing high art. Woolf argued that women would produce high art if aspiring female artists had their own money and ''a room of one's own,'' just as men have, to explore their innate talents.

Works in Critical Context

Critics have praised the uniqueness of Farah’s writing. ‘‘The novels are, in the widest sense, political but are never simplistic or predictable,’’ declares Angela Smith in Contemporary Novelists. The author’s first two novels, From a Crooked Rib (1970) and A Naked Needle (1976), were both written before his self-imposed exile from his home country. He is better known, however, for his trilogy of novels about the collapse of democracy in Somalia known as ‘‘Variations on the Theme of an African Dictatorship.’’

From a Crooked Rib and A Naked Needle. He depicted the inferior status of women in Somali society in his first novel, From a Crooked Rib (1970), the first work of fiction to be published in English by a Somali author. According to Kirsten Holst Petersen, who has called Farah ‘‘the first feminist writer to come out of Africa,’’ From a Crooked Rib will likely ‘‘go down in the history of African literature as a pioneering work, valued for its courage and sensitivity.’’ Other critics believe the work is substandard, however. Florence Stratton wrote: ‘‘Stylistically and technically, From a Crooked Rib is a most unsatisfactory piece of work. It does not prepare the reader for the elegant prose, intricate structures, or displays of technical virtuosity of the later novels.’’ Farah’s next novel, A Naked Needle (1976), revolves around a British-educated young man, Koschin, whose search for a comfortable existence in post-revolutionary Somalia is complicated by the arrival of a former lover from England who intends to marry him. Reinhard W. Sander observed: ‘‘Next to Wole Soyinka’s The Interpreters, [A Naked Needle] is perhaps the most self-searching [novel] to have come out of post-independence Africa.’’

The “Variations on the Theme of an African Dictatorship” Trilogy. These works document the demise of democracy in Somalia and the emerging autocratic regime of Major General Muhammad Siyad Barre, referred to as the ‘‘General’’ in this series. The first volume of the trilogy, Sweet and Sour Milk (1979), focuses upon a political activist whose attempts to uncover the circumstances of his twin brother’s mysterious death are thwarted by his father, a former government interrogator and torturer. Sardines (1981), the next installment, depicts life under the General’s repressive administration and examines social barriers that limit the quest for individuality among modern Somali women. Critics admired Farah’s realistic evocation of his heroine’s tribulations. Charles R. Larson stated: ‘‘No novelist has written as profoundly about the African woman’s struggle for equality as has Nuruddin Farah.’’ Close Sesame (1982), the final volume of the trilogy, concerns an elderly man who spent many years in prison for opposing both colonial and postrevolutionary governments. When his son conspires to overthrow the General’s regime, the man’s attempts to stop the coup cost him his life. According to Peter Lewis, ‘‘Close Sesame analyzes the betrayal of African aspirations in the postcolonial period: the appalling abuse of power, the breakdown of national unity in the face of tribal rivalry, and the systematic violation of language itself.’’

Responses to Literature

1. Both Farah’s Sardines and Freidan’s The Feminine Mystique deal with, in one way or another, the sexuality of women and the role that societal conventions play in a woman’s perception of her body. Read these texts, and then, in a short essay, compare how each of these authors approaches these delicate subjects. Who seems to be the intended audience for each text? Based on the text, what changes do you think each author would like to see made in society? Make sure to cite specific passages from each text in support of your argument.

2. Farah has been praised for his ability to write from a female’s point of view, considered by some a difficult task for a man. Read From a Crooked Rib. In a short essay, describe the narrative techniques, turns of phrases, and other details of the novel that make Farah’s portrayal of his female protagonist so effective.

3. In his book Sardines, the balance in the fertility cycles is broken by the socially enforced clitoral circumcision. Forced female circumcision has persisted in many African countries, despite attempts by outside agencies, and authors like Farah, to put an end to the practice. Using the Internet and the library, research the history of forced female circumcision in Africa—its origins, its purpose, and its significance— and then write a short essay in which you explore the question: Why does forced circumcision persist in these countries? Describe your emotional reaction to the inclusion of this issue in Farah’s novel.

4. Read Variations on the Theme of an African Dictatorship. This trilogy is meant to depict the political changes in Somalia and includes references to real- life figures. After having read the text, use the Internet and the library to research events described in Farah’s text. Which events does Farah choose to fictionalize or exaggerate in his trilogy? In your opinion, why does he choose these events to fictionalize and not others?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Bardolph, Jacqueline. ‘‘The Literary Treatment of History in Nuruddin Farah’s Close Sesame.’ Proceedings of the Third International Congress of Somali Studies, Ed. Annarita Publieli. Rome: Pensiero Scientifico, 1988.

Killam, G. D., ed. The Writings of East and Central Africa. London: Heinemann, 1984.

Little, Kenneth. Women and Urbanization in African Literature. New York: Macmillan, 1981.

Wright, Derek. Emerging Perspectives on Nuruddin Farah. Trenton, N.J.: African World Press, 2002.

Periodicals

Adam, Ian. ‘‘The Murder of Soyaan Keynaan.’’. World Literature Written in English (Autumn 1986).

________. ‘‘Nuruddin Farah and James Joyce: Some Issues of Intertextuality.'' World Literature Written in English (Summer 1984).

Cochrane, Judith. ‘‘The Theme of Sacrifice in the Novels of Nuruddin Farah.'' World Literature Written in English (April 1979).

Mnthali, Felix. ‘‘Autocracy and the Limits of Identity: A Reading of the Novels of Nuruddin Farah.’’ Ufahamu (1989).

Moore, G. H. ‘‘Nomads and Feminists: The Novels of Nuruddin Farah.'' International Fiction Review (Winter 1984).

Sparrow, Fiona. ‘‘Telling the Story Yet Again: Oral Traditions in Nuruddin Farah’s Fiction.’’ Journal of Commonwealth Literature (1989).