World Literature

Athol Fugard

BORN: 1932, Middleburg, South Africa

NATIONALITY: South African

GENRE: Drama, fiction

MAJOR WORKS:

The Blood Knot (1961)

Boesman and Lena (1969)

Sizwe Bansi Is Dead (1972)

“Master Harold” ... and the Boys (1982)

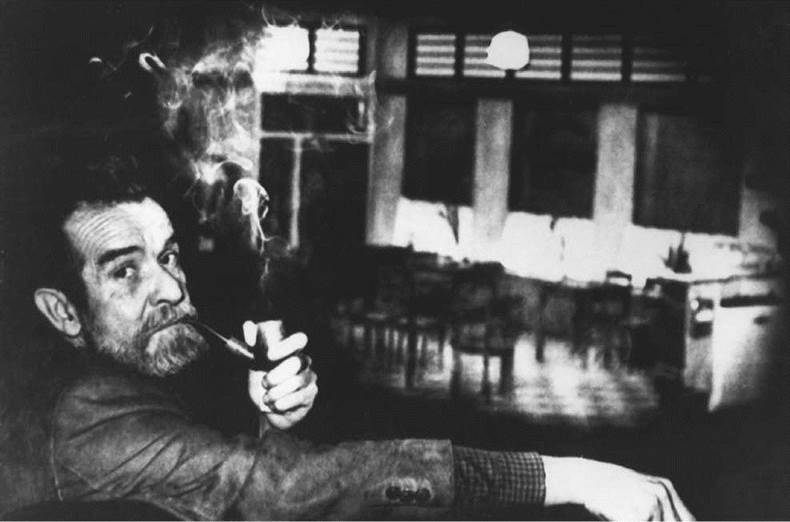

Athol Fugard. Fugard, Athol, photograph. AP images.

Overview

Athol Fugard is South Africa’s foremost playwright and one of the leading dramatists of the latter twentieth century. A writer, director, and performer, he has worked collaboratively with performers across the racial divide and transformed South African theater. In his work, Fugard focused relentlessly on the injustices perpetuated by South Africa’s apartheid system of government. As his plays make viscerally clear, all South Africans have been the victims of the tragic legacy of apartheid.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

Racial Divide in Youth. Harold Athol Lannigan Fugard was born on June 11, 1932, on a farm in Cape Province, in the semidesert Karoo region of South Africa. In 1935, the family moved to Port Elizabeth, which became his lifelong home. His father, a crippled former jazz pianist of English stock, amused the boy with fantastic stories and confused him with his unabashed bigotry. His mother—an Afrikaner descended from Dutch settlers who had been coming to South Africa for trade purposes since the late seventeenth century—supported the family by managing their boardinghouse and tearoom. Fugard credits his mother with teaching him to view South African society with a critical eye.

By the 1930s, legal and social discrimination was firmly in place against South Africans of non-European ancestry. After slavery ended there in 1833, blacks were required to carry identification cards, and in the early twentieth century, the Native Land Acts of 1913 and 1936 prohibited blacks from owning land in areas of white residence. Only 13 percent of the land in South Africa was put aside for blacks, though they formed 70 percent of the population. By the 1930s, Afrikaners— the more uncompromising supporters of segregation than English-speaking whites—began using the term apartheid to refer to their ideas of racial separation.

As a white child growing up in a segregated society, Fugard resisted the racist upbringing offered him, but could not escape apartheid’s influence. He insisted that the family’s black servants call him Master Harold, and one day, he spat in the face of Sam Semela, a waiter in the Fugard boardinghouse, who was the best friend he had as a child.

Transformation of Racial Beliefs. Fugard attended Catholic schools as a youth. He had his first experience of amateur dramatics in secondary school, as an actor and as director of the school play. A scholarship took him to the University of Cape Town, where he studied ethics. However, he dropped out just before graduation and toured the Far East while working aboard a merchant ship. Fugard has remarked that living and working with men of all races aboard the Graigaur liberated him from the prejudice endemic among those with his background. Within a year he was back home, working as a freelance journalist for the Port Elizabeth Evening Post. By then, he knew he wanted to write.

As Fugard prepared for such a career, apartheid policies had become more strict in South Africa. When the Afrikaner-backed Nationalist Party was elected into office in 1948, more apartheid laws began to be put into place. Such laws made it illegal for blacks to use first-class coaches of railroad cars and for marriage between people of different races and divided the country into regions for blacks, whites, and coloreds (those of mixed race). Black South Africans had fought such discriminatory practices since the early twentieth century, but by the late 1940s, one major group, the African National Congress (ANC), increased its tactics to include strikes and acts of civil disobedience.

After Fugard met Sheila Meiring, an actress from Cape Town, and married her in 1956, he developed an interest in drama and started off as an actor. The couple moved to Johannesburg and began collaborating with a group of black writers and actors in the ghetto township of Sophiatown. Fugard worked briefly as a clerk in the Native Commissioner’s Court, which tried cases against nonwhites arrested for failing to carry identification. Observing the machinery of apartheid up close opened his eyes to its evil effects. Out of these experiences came No-Good Friday (1958) and Nongogo (1959), his first two full-length plays, which Fugard and his black actor friends performed for small private audiences.

The Blood Knot. Fugard moved to England in 1959 to write, but his work received little attention there, and he realized he needed to work in the context of his home country. South African apartheid policies were firmly in place, and blacks, coloreds, and Asians (a racial category added to apartheid laws in the 1950s) were fully, legally segregated from whites. When he returned home, he completed his first and only novel. Tsotsi (1980) concerns a young black hoodlum who accidentally kidnaps a baby and is compelled to face the consequences of his actions. Fugard tried to destroy the manuscript, but a copy survived and was published in 1980.

While finishing Tsotsi, Fugard wrote his breakthrough play, The Blood Knot (1961). The idea came to him in 1960 after the Sharpeville massacre, when police killed blacks protesting the apartheid pass laws—a turning point for all South Africans. The Blood Knot portrays the oscillating sense of conflict and harmony between two brothers born to the same mother. Morris has light skin and can pass for white. He confronts the truth about his identity when he returns home to live with his darkskinned brother, Zach.

Fugard played the role of Morris himself. The play was first presented in 1961 to an invited audience. At that time, blacks and whites were banned from appearing on the same stage or sitting in the same audience. From the opening image of a shabby, pale-skinned man preparing a footbath for a black man, The Blood Knot struck South Africa’s segregated culture like a bombshell. In 1962, Fugard supported a boycott against legally segregated theater audiences.

Collaborative Theater. Returning to Port Elizabeth, Fugard helped found an all-black theater group called the Serpent Players. Despite police harassment, the group gave workshops and performed a variety of works for local audiences. Fugard also began to take his work overseas. His passport was revoked in 1967 after The Blood Knot aired on British television. Even after the government banned his plays, he refused to renounce his country. Fugard maintained that love, not hate, for South Africa would help that country break the chains of apartheid. In 1971, his travel restrictions were lifted, and Fugard traveled to England to direct his acclaimed play Boesman and Lena (1969), an unflinching portrayal of mutual hostility and dependence between a homeless mixed-race couple who wander without respite.

As Fugard gained increasing critical acclaim, he further refined his model of experimental, collaborative drama. He created his pieces with the actors, and staged them in small, unofficial venues, with minimal sets and props. With two talented black actors, John Kani and Winston Ntshona, Fugard produced three improvisational works with political themes: Sizwe Bansi Is Dead (1972), in which a man assumes a dead man’s identity in order to obtain an apartheid pass; Statements After an Arrest Under the Immorality Act (1972), about an ‘‘illegal’’ biracial love affair; and The Island (1973), in which two political prisoners stage Sophocles’ play Antigone to express solidarity and resistance. The ‘‘Statements Trilogy’’ was staged in London and New York to great acclaim. Another experiment was the nearly wordless drama Orestes (1971), which juxtaposes the Greek tragedy with a contemporary protest in South Africa, to explore the impact of violence on both its victims and its perpetrators.

Protests and repression grew more intense in the late 1970s in South Africa. Beginning in 1976, blacks in Soweto violently protested the use of Afrikaans in schools, and the suppression by South African police of the riots left 174 blacks dead and 1,139 injured. New protest groups and leaders emerged among young blacks. More protests followed the death of one such leader, Steven Biko, while in police custody. In this environment, the playwright turned to more personal concerns. In A Lesson from Aloes (1978), a Dutch Afrikaner declines to defend himself when accused of betraying his only friend to the police, and for most of the play the audience is unsure of his innocence.

No Easy Answers. Fugard’s plays of the 1980s continued to probe the social and psychological dimensions of his nation’s crisis, which deepened with the declaration of a state of emergency in 1985. A new constitution came into force that reinforced the political control of whites, leading to increased strikes and conflicts by nonwhites as well as international pressure for change. The emergency regulations gave police the power to arrest without warrants and detain people indefinitely without charging them or notifying their families.

Some of his works opened in the United States and were not staged in South Africa. The Road to Mecca (1984), explored the solitary white consciousness through an elderly artist who isolates herself at home, producing sculptures from cement and wire. Fugard departed from realism with A Place with the Pigs (1987), a parable concerning a Soviet soldier who hides in a pigsty for forty years. Both plays premiered in the United States.

My Children! My Africa! (1989) was the first Fugard play to premiere in South Africa in years. The work was inspired by the story of a black teacher who refused to participate in a school boycott and was later murdered in Port Elizabeth by a group that believed he was a police informer. The play provoked controversy with its implicit critique of the school boycotts organized by the African National Congress.

Postapartheid. Fugard’s plays consistently place multiple viewpoints into dialogue, and exempt no position from scrutiny. This stance coincides with the principles of ‘‘truth and reconciliation’’ with which South Africa attempted to heal its wounds in the 1990s. When F. W. de Klerk became the head of the National Party in the late 1980s, he began instituting a series of reforms, including the legalization of such groups as the ANC. Apartheid laws began to be repealed in the early 1990s, the ANC was elected into power in the mid-1990s, and black former political prisoner Nelson Mandela became president in 1994. The first of Fugard’s postapartheid plays, Playland (1993), is a case in point. As two strangers—one black, one white—reveal their darkest secrets to each other in an amusement park, the inherited nightmares of apartheid surface, offering no easy answers and forcefully posing the question: Can the sins of the past be forgiven, if not forgotten?

Valley Song (1996), reflects the playwright’s optimistic view of his nation’s future after the inauguration of Mandela. It also reveals its author’s inward focus: Fugard placed himself onstage as the self-styled author. Two of his more recent works were also tinged with nostalgia. The Captain’s Tiger (1997) is a reflection on his months in the merchant marines, while Exits and Entrances (2004) explores his early theatrical career. Fugard continues to make his home in South Africa.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Fugard's famous contemporaries include:

Nadine Gordimer (1923—): A South African fiction writer and antiapartheid activist who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1961. She wrote Burger's Daughter (1969).

Wole Soyinka (1934—): The Nigerian playwright, poet, and essayist, who wrote the play Kongi's Harvest (1970).

Desmond Tutu (1931—): The Anglican archbishop of Cape Town, head of South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and Nobel Peace Prize winner.

Harold Pinter (1930—): An English playwright, screenwriter, and poet famous for such plays as The Homecoming (1964).

August Wilson (1945-2005): The American dramatist whose Pittsburgh Cycle chronicles the African-American experience in the twentieth century.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

The theater of Athol Fugard lays bare the consequences of racial prejudice, as do the following works for the stage:

Othello (ca. 1603), a play by William Shakespeare. In this brilliant tragedy, Iago plays on sexual as well as racial anxieties to undo the Moor of Venice.

A Raisin in the Sun (1959), a play by Lorrraine Hansberry. In this landmark play, Walter Lee and Lena Younger face discrimination when they buy a house in a white neighborhood.

Blues for Mister Charlie (1964), a play by James Baldwin. This meditation on racism was written in the wake of the assassination of civil rights leader Medgar Evers.

Dream on Monkey Mountain (1967), a play by Derek Walcott. A metaphorical play in which the downtrodden consciousness of a colonized society is symbolized through the hallucinations of an aging charcoal vender named Makak.

For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/ When the Rainbow Is Enuf (1975), a play by Ntozake Shange. A hard-hitting poem/play about the experience of African American womanhood.

Works in Literary Context

Fugard has created some classic works for the stage, but he acknowledges little influence from prior dramatists. The small casts, sparse sets, and flat dialogue in his plays reveal an aesthetic debt to Samuel Beckett. Reading William Faulkner and Tennessee Williams early in his career confirmed his sense that he wanted to create drama that was, above all, local. Echoing one of his favorite authors, Albert Camus, Fugard says in Notebooks, 19601977 that the ‘‘true meaning’’ of his life’s work is ‘‘just to witness’’ as truthfully as he can ‘‘the nameless and destitute’’ of his ‘‘one little corner of the world.’’ The greatest influence on his work comes from his collaborators, especially black performers, such as Zakes Mokae and John Kani, who carry on a rich, indigenous storytelling tradition.

Psychology in Intimate Relationships. According to Dennis Walder in Athol Fugard, Fugard’s plays ‘‘approximate ... the same basic model established by The Blood Knot, a small cast of ‘marginal’ characters is presented in a passionately close relationship embodying the tensions current in their society.’’ For example, Boesman expresses his hatred of the South African political system in the form of violence toward Lena, who suffers Boesman’s misplaced rage with dignity. Similarly, in My Children! My Africa! the confrontation between the elderly black schoolteacher and the militant student reflects a gap between generations and ideologies. A Fugard play invariably reveals the damage that unjust social institutions inflict on the psychic and ethical integrity of individuals. Fugard forces audiences to consider his characters in their complexity, not to characterize them as good or bad.

The Dramatic Image. Fugard’s model is also consistent in the way his plays are produced. The actors are directly involved in the play’s creation. Unnecessary scenery, costumes, and props are stripped away, creating what the Polish director Jerzy Grotowski called ‘‘poor theater,’’ although Fugard was practicing it before he encountered Grotowski’s work. For Fugard, a play exists only when it is performed for an audience. The function of drama is to evoke the truth of what he calls ‘‘the living moment.’’ The intense, revelatory moments in his plays are usually expressed in images, such as the moment when Hally spits in Sam’s face in Master Harold, or when Zach looms above his brother Morris, provoked by racist insults into attack, in The Blood Knot.

Works in Critical Context

Fugard is highly regarded by literary and theater critics. Some have called him the greatest playwright of his era. He commands respect for his unfailing opposition to apartheid and for his sophisticated explorations of its subtly destructive effects. Critics have also appreciated his ability to elicit emotion without declining into melodrama. Most South African drama, especially the nation’s lively alternative theater, bears the stamp of Fugard’s work. His acclaim is greater outside his home country. In the United States, he is one of the most frequently performed living playwrights.

Racial Critique. Not all critics of apartheid, however, have appreciated Fugard’s works. Over the years, some have faulted him for his failure to denounce the system’s injustices in a more confrontational manner. His plays are open to multiple interpretations, and thus to controversy. For example, some Afrikaners believed the message of The Blood Knot was that blacks and whites could not live together peaceably, while some black critics called the work racist. Most now embrace the play as a sad commentary on the way racism has twisted and tangled our understanding of brotherhood and humanity.

Amid the racial polarization of apartheid, Fugard walked a fine line. Critic Jeanne Colleran wrote in Modern Drama that ‘‘Fugard cannot write of Johannesburg or of township suffering without incurring the wrath of black South Africans who regard him as a self-appointed and presumptuous spokesman; nor can he claim value for the position previously held by white liberals without being assailed by the more powerful and vociferous radical left.’’

‘‘Master Harold’’... and the Boys. One of many of Fugard’s plays to receive acclaim was ‘‘Master Harold’’... and the Boys. Reviewing the New York production, Robert Brustein of the New Republic noted that ‘‘Master Harold seems to be a much more personal statement than his other works; it also suggests that his obsession with the theme of racial injustice may be an expression of his own guilt, an act of expiation. Whatever the case, his writing continues to exude a sweetness and sanctity that more than compensates for what might be prosaic, rhetorical, or contrived about it.’’

Responses to Literature

1. Do you support Athol Fugard’s claim that he is not a political writer? Why or why not? What constitutes political writing? Who, in your opinion, is a successful political writer today? How so? Write a paper in which you explain your arguments.

2. How does the experimental nature of Fugard’s theater affect the content and tone of his plays? Create a presentation using classmates as actors to illustrate your findings.

3. Citing three or more of Fugard’s plays, write about the role that violence plays in his work. For what type of audience would this violence have an appeal?

4. In what ways does Fugard believe that white South Africans have been affected by the nation’s racial legacy? How does he demonstrate these effects? Write a paper in which you explain your arguments.

5. What can you learn about love and intimate friendship by studying The Blood Knot, Boesman and Lena, and ‘‘Master Harold’’... and the Boys? Create a presentation that demonstrates your findings.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Benson, Mary. Athol Fugard and Barney Simon: Bare Stage, a Few Props, Great Theatre. Randburg, South Africa: Ravan, 1997.

Blumberg, Marcia, and Dennis Walder, eds. South African Theatre as/and Intervention. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1999.

Gray, Stephen, ed. Athol Fugard. Johannesburg: McGraw Hill, 1982.

Heywood, Christopher, ed. Aspects of South African Literature. London: Heinemann, 1976.

Kavanagh, Robert. Theatre and Cultural Struggle in South Africa. London: Zed, 1985.

Vandenbroucke, Russell. Truths the Hand Can Touch: The Theatre of Athol Fugard. New York: Theatre Communications Group, 1985.

Walder, Dennis. Athol Fugard. London: Macmillan, 1984.

Periodicals

Brustein, Robert. Review of ‘‘Master Harold’’... and the Boys. New Republic, June 23, 1982, 30-31.

Cohen, Derek. ‘‘Athol Fugard’s Boesman and Lena.’ Journal of Commonwealth Literature 12 (April 1978): 78-83.

Colleran, Jeanne. ‘‘Athol Fugard and the Problematics of the Liberal Critique.’’ Modern Drama 38 (Fall 1995): 389-467.

Durbach, Errol. ‘‘Surviving in Xanadu: Athol Fugard’s Lesson from Aloes.’’ Ariel 20 (January 1989): 5-21.

Gussow, Mel. Profiles. ‘‘Witness: Athol Fugard.’’ New Yorker, December 20, 1982, 47-94.

Post, Robert M. ‘‘Racism in Athol Fugard's ‘‘Master Harold’’... and the Boys.’ World Literature Written in English 30, no. 1 (1990): 97-102.

Richards, Lloyd. ‘‘The Art of Theater VIII: Athol Fugard.’’ Paris Review 111 (1989): 128-51.