World Literature

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

BORN: 1749, Frankfurt-am-Main, Germany

DIED: 1832, Weimar, Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, Germany

NATIONALITY: German

GENRE: Poetry, Fiction, drama, nonfiction

MAJOR WORKS:

The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774)

Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship (1795)

Faust, Part One (1808)

Faust, Part Two (1832)

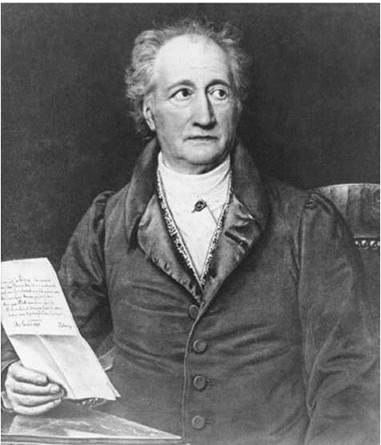

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Von Goethe, Johann Wolfgang, 1828 painting by Joseph Stieler. AP Images.

Overview

Though he lived in late eighteenth-century Germany, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe was a true Renaissance man whose influence touched not only literature, poetry, and drama, but ranged into philosophy, theology, and science. Best known for his novels and poems, Goethe influenced a generation of philosophers and scientists and created some of Germany’s best-known works of literature. History has ranked Goethe alongside William Shakespeare, Homer, and Dante Alighieri: in the words of Napoleon I upon meeting the eminent poet, ‘‘There’s a man!’’

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe was born in Frankfurt-am-Main in the state of Hessia in Germany on August 28,1749. The eldest son of an imperial counselor and the mayor’s daughter, Goethe balanced the personalities of his reserved, stern father, Johann Kaspar Goethe, and his impulsive, imaginative mother, Katharina Elisabeth Textor Goethe.

Law Degree and Attempts at Writing. Goethe was educated at home by his father and private tutors, who taught him languages, drawing, dancing, riding, and other subjects. The theater would have a profound impact on Goethe, who was allowed free access to the performances of a French theatrical troupe when the French occupied Frankfurt during the Seven Years War (1756-1763). He began writing early, composing religious poems, a prose epic, and even his first novel, which was written in German, French, Italian, English, Latin, Greek, and Yiddish, by the time he was sixteen years old.

Though he was more interested in literature than law, Goethe obeyed his father’s wishes and began studying law in Leipzig in 1768. At this time, Goethe composed some of his early plays and poems. After going home in 1768 to recover from a serious illness, Goethe went to Strasbourg in 1770 to complete his law degree.

In Strasbourg, Goethe engrossed himself in reading, artistic discovery, and writing. There, he met Johann Gottfried Herder, a philosopher and poet who introduced him to new literary works, including the novels of English writers Laurence Sterne, Oliver Goldsmith, and Henry Fielding, that would prove influential in his later writing.

Doomed Love Affairs and the Sturm und Drang Sensation. After returning to Frankfurt to practice law in 1771, Goethe also launched his writing career. In addition to his legal practice, he visited with literary friends, wrote book reviews, traveled in Germany and Switzerland, and fell in love three times. It was the falling in love that would have the greatest impact on his career as a writer. Each relationship ended in tragedy: his entanglement with Charlotte Buff ended when he discovered she was engaged to his friend; he then fell in love with a married woman; and his engagement to Anna Elisabeth Schonemann was broken off in September 1775. However painful these attachments, they inspired a number of poems, and Goethe became a kind of center for the Sturm und Drang (‘‘Storm and Stress‘‘) artistic movement that was sweeping Germany.

Inspired by ancient poetry, the Sturm und Drang movement tried to establish new political, cultural, and literary forms for Germany as a replacement for the French neoclassical tradition that dominated much literature and culture. The German movement was characterized by extreme emotion, individual feeling, even irrationality—all responses to what was seen as the cold rationalism of French neoclassicism. The members of the German movement idolized writers like William Shakespeare, whom Goethe celebrated as a poet of nature, writing an influential speech on Shakespeare’s birthday that would prove a major milestone for Shakespearean literary criticism. He began to imitate Shakespeare’s dramatic style in his own prose plays, focusing also on satire and poetic dramas. However, his most influential work of the period, Die Leiden des jungen Werthers (The Sorrows of Young Werther), would be inspired by the doomed relationship with Charlotte Buff that almost drove Goethe to suicide. This novel in letters, which explores themes of love, philosophy, religion, and nature, established Goethe as an overnight celebrity. The impact of Werther on Goethe’s contemporaries is hard to overestimate: not only did ‘‘Werther fever’’ spread throughout Europe and Asia, but its sentimental tale of love and suicide encouraged a fad of melancholic, emotional romanticism.

The Weimar Years. In 1775, Goethe received an invitation to join Duke Karl August, a young prince, in Weimar. Goethe, who was soon given a position of minister of state, would live there for the remainder of his life. He took on responsibility for the duchy’s economic welfare, concerning himself with horticulture, agriculture, and mining; however, his growing responsibilities proved an irritating distraction from his writing. At this time, Goethe entered into an intense friendship with Charlotte von Stein, the wealthy wife of a court official and the most intellectual of Goethe’s loves.

Though Goethe was a statesman and a writer, his interests extended to topics like alchemy, phrenology, botany, anatomy, and medicine. He made important discoveries in anatomy and even came up with an influential theory on plant metamorphosis. Overburdened by competing interests and responsibilities, Goethe fled to Italy in 1786, taking a journey that would turn out to be an act of artistic rebirth.

Italian Journey for Artistic Inspiration. In Italy, Goethe kept a detailed diary for Charlotte von Stein. In it, he recorded his reflections and inspirations, from his observations of the customs of the people to his studies of painting, sculpture, botany, geology, and history. He revised three influential ‘‘classical’’ plays: Egmont; Iphigenie auf Tauris, and Torquato Tasso. In these plays he drew on themes of conflicted love, intrigue, and mythology.

Upon his return to Weimar in 1788, Goethe experienced several life changes. He was relieved of all of his official duties aside from association with the court theater and libraries, and his relationship with Charlotte von Stein came to an end. Around this time, he entered into a relationship with Christiane Vulpius, a woman who would become his wife and bear him several children, of whom only one, Julius August Walther, would survive. The uneducated Vulpius was looked down upon by Goethe’s courtly friends, who cruelly referred to her as Goethe’s ‘‘fatter half.’’

Unconcerned by public opinion, Goethe continued to study and write, though his literary output in the 1790s was sparse compared to that of his earlier years. After his Italian journey, Goethe was increasingly interested in classicism, writing his Roman Elegies during this time. These poems, which show a German traveler finding gradual acceptance into a Roman world of history, art, and classical poetry, were considered scandalous upon publication, but are now considered among the generation’s greatest love poems.

Friendship with Schiller and Major Literary Achievements. During this time, Goethe formed one of the most influential relationships of his life: a friendship with Friedrich von Schiller, a poet and Sturm und Drang contemporary. After a rocky initial acquaintance, the pair formed a mutually supportive relationship, producing literary journals and helping forge a classical German literature. Hailed by key figures in Germany’s growing Romantic movement, Goethe continued to produce poems, plays, satire, and ballads.

Goethe’s next accomplishments would profoundly affect world literature: his novel William Meister’s Apprenticeship is considered a classic Bildungsroman (a novel that focuses on the protagonist’s growth from childhood to maturity). However, Wilhelm Meister was not Goethe’s only accomplishment during the 1790s: He rewrote and completed his dramatic poem Eaust between the 1790s and 1808. The work, which tells of the legendary Dr. Faust’s deal with the devil, would prove immensely popular and influential, inspiring countless works of music, theater, and literature. The play can be seen as a commentary on the pitfalls of the Industrial Revolution, a period of rapid modernization in agriculture, industry, and transportation that started in Europe in the late eighteenth century. Dr. Faust represents modern man’s thirst for dominion over nature. But nature, Goethe warns, has a power not fully understood by men, even geniuses like Faust, and mankind tinkers with nature at its peril.

A Meeting with Napoleon. Around this time, Goethe’s friend Schiller died, and France’s emperor Napoleon and his army were marching from victory to victory across Europe. One such victory was at the Battle of Jena in 1806, which took place just twelve miles from Goethe’s home in Weimer. The French sacked Weimar, but Goethe’s home was spared because of Napoleon’s admiration of Goethe’s work. The feeling was mutual, apparently. Goethe kept a bust of Napoleon prominently on display in his study. The two famously met in 1808 and briefly discussed literature.

Goethe would continue to be productive for the remainder of his life, publishing an influential treatise on color, writing an autobiography, and recording his conversations and letters with luminaries of the era. Though his uncommon attitudes toward society and politics alienated him from many of his peers, Goethe was thought of as Germany’s greatest writer at the time of his death in 1832. His sequel to the first part of Eaust, which was published after his death, is thought to be his most mature work. Goethe was buried next to his friend Friedrich von Schiller in Weimar.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Goethe's famous contemporaries include:

Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860): a German philosopher best known for his work on the limits of human knowledge.

Charles Darwin (1809-1882): an English naturalist and originator of the theory of evolution.

Jane Austen (1775-1817): a British novelist known for her comedies of manners.

Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821): a French political leader known for his military prowess.

Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826): the third president of the United States and renowned inventor and philosopher.

Emily Bronte (1818-1848): a British novelist known for her classic novel Wuthenng Heights.

Works in Literary Context

Though Goethe’s plays and poems are considered among the finest in German literature, he was never shy about pointing out his many literary influences. In turn, his own work proved profoundly influential to writers of the Sturm und Drang and Romantic movements along with writers and intellectuals as diverse as Nikola Tesla and Hermann Hesse.

As a young man, Goethe read widely in French, Italian, and the classical languages, but his writing was as influenced by the intellectual society of eighteenth- century Germany as it was by literary figures. During his Sturm und Drang period, Goethe embraced writers such as William Shakespeare, Oliver Goldsmith, and Hans Sachs, a sixteenth-century German satirist, as well as classical figures such as Homer.

The Bildungsroman. Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship is considered a classic example of the Bildungsroman, a story that follows the growth and maturation of a character from youth to maturity. English author Charles Dickens’s Great Expectations (1860), one of the most famous English-language Bildungsromans is considered a direct descendant of Goethe’s work. The Bildungsroman form has remained a favorite among fiction writers since Goethe’s time. Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre (1847), Somerset Maugham’s Of Human Bondage (1915), Hermann Hesse’s Siddhartha (1922), John Knowles’s A Separate Peace (1959), and Rudolfo Anaya’s Bless Me, Ultima (1972) are all widely studied Bildungsromans.

Defining German Literature and Culture. Much of Goethe’s literary career concerned weighing the influences of other periods and searching for a German national language and literature. Unsatisfied by the French influence that saturated that period’s philosophy and literature, Goethe turned to neoclassicism, upholding the influence of ancient writers, studying classical art and architecture, and embracing Roman ideals of beauty and culture.

Though he was never considered a true Romantic poet, Goethe’s works had an undeniable influence in Romantic circles. His The Sorrows of Young Werther attracted a following that would go on to influence the moody writings of the young Romantics. During the last years of his life, he was considered a living monument to a German national literature he had helped create and define.

Goethe’s influence was more than just literary: his philosophical works went on to inspire the likes of Friedrich Nietzsche, Carl Gustav Jung, and Ludwig Wittgenstein, while his scientific writings inspired Charles Darwin.

In addition to his literary and scientific influence, Goethe researched German cultural and folk traditions. His cultural research resulted in many of the Christmas traditions observed in the Western world today. In addition, Goethe’s theories on geography and culture (namely, that history and geography shape personal habits) are still relevant today. His balanced view of rational thought and aesthetic beauty would go on to shape the work of artists and thinkers like Ludwig van Beethoven, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and many others.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Goethe's Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship is considered to be the epitome of the Bildungsroman, a "self-cultivation" novel that follows a protagonist's development from childhood to maturity. Here are a few other examples of the genre:

Persepolis (2003), a graphic novel by Marjane Satrapi. This work chronicles the author's childhood in Iran during the Islamic Revolution.

A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (1943), a novel by Betty Smith. Smith traces the childhood and maturation of Francie Nolan, an Irish-American living in New York in the early twentieth century.

David Copperfield (1850), a novel by Charles Dickens. David Copperfield transforms from awkward child to writer in this classic English Bildunsgroman.

Harry Potter series (1997-2007), novels by J.K. Rowling. The seven-book Potter series follows a young wizard and his friends as they grow up and take on adult responsibilities.

Works in Critical Context

Goethe was already considered the premier German poet and writer in his own lifetime and has since enjoyed a long career of critical success. However, the statement ‘‘Against criticism a man can neither protest nor defend himself; he must act in spite of it, and then it will gradually yield to him’’ is attributed to Goethe, implying that his critical reception was not always golden.

The Sorrows of Young Werther. Goethe was often a figure of public controversy, with his work criticized for its romantic and sexual content, its rejection of French Enlightenment ideals, and its pagan or antireligious themes. Though The Sorrows of Young Werther appeared to almost unanimous critical success, it was controversial for its romantic excess, which led to a rash of suicides among Werther fanatics.

After Werther, Goethe faded into semi-obscurity, reemerging with his classical plays and receiving acclaim from the young movement of Romantic poets who responded to his sensitivity and natural approach. He was praised by Novalis, a Romantic philosopher and author, as ‘‘the true representative of the poetic spirit on earth;’’ however, Novalis and other Romantics soon turned against what they saw as Goethe’s political apathy and elitist views. In his work The Life of Goethe: A Critical Biography, author John R. Williams points out that Goethe did not court good opinion during his life, but rather tried to bring other Germans up to his own standards of education and culture, remaining indifferent to public criticism.

Faust. Goethe’s almost universally praised verse drama Faust is considered one of the world’s greatest plays. Based on an old Christian legend that Goethe had seen dramatized in a puppet show during his childhood, Faust utilizes a mythological, magic-laced context to explore with broad appeal and compelling results the dilemma of modern man. Goethe’s drama made the legendary figure of Faust one of the best-known literary characters of all time. The ever-seeking, never-satisfied Faust has come to symbolize the human struggle and yearning for knowledge, achievement, and glory. Critic George Santayana wrote that Faust ‘‘cries for air, for nature, for all existence.’’ Few critics have found fault with the play, and those who have, like Margaret Fuller, fault Goethe only in comparisons to such titans of world literature as Dante. She wrote, ‘‘Faust contains the great idea of [Goethe’s] life, as indeed there is but one great poetic idea possible to man—the progress of a soul through the various forms of existence. All his other works, whatever their miraculous beauty of execution, are mere chapters to this poem, illustrative of particular points. Faust, had it been completed in the spirit in which it was begun, would have been the Divina Commedia of its age.’’ Fuller mainly criticizes the second part of the play for being out of keeping with the first part.

Politics and Culture Goethe’s critical reception after death has been mixed. His work was spurned by German nationalists who criticized his adoption of international philosophies, while his life was condemned as immoral due to his many love affairs, including one with a longtime live-in mistress. However, Goethe scholarship grew and changed, undergoing an important phase in the post-World War II years in which Germans grappled with questions of identity and national culture. Though more recent literary movements have tried to distance themselves from the German classical literature born in Weimar, Goethe scholarship has continued. Recent works of criticism have focused on Goethe’s humor, his position in relation to Marxism, and his place between classical and Romantic literature.

Responses to Literature

1. Goethe combined his literary work with studies in science, philosophy, history, and culture. What might such a broad set of interests have contributed to Goethe’s literary work? Or might his varied interests have detracted from his work? Is there a particular area of study that is more reflected in his works than others? Explain.

2. The Sorrows of Young Werther set off an international sensation with its melancholy and overblown sentimentality. What other works of literature have sparked international fads? How have those fads presented themselves and how long did they last? Why were those fads particularly popular?

3. Goethe was strongly influenced by his friendship with Friedrich von Schiller, a German poet next to whom he was buried. Using your library and the Internet, research another pair of influential writers whose friendship contributed to their literary work. What do you think attracted these two friends to one another?

4. Faust is considered one of the most influential works of German literature and has spawned a number of related works by other writers and artists. Using your library and the Internet, compare and contrast two separate adaptations of Goethe’s Faust. Which of these adaptations holds more relevance for today’s audience? How so?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Atkins, Stewart P. Goethe’s Faust: A Literary Analysis. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1958.

Brandes, Ute Thoss. Gunter Grass. Berlin: Edition Colloquium, 1998.

Graham, Ilse. Goethe: A Portrait of the Artist. Berlin and New York: De Gruyter, 1977.

Lewes, George Henry. The Life and Works of Goethe. London: Nutt, 1855.

Richards, Robert L. The Romantic Conception of Life: Science and Philosophy in the Age of Goethe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002.

Sharpe, Lesley. The Cambridge Companion to Goethe. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

Ugrinsky, Alexej. Goethe in the Twentieth Century. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1987.

Williams, John R. The Life of Goethe: A Critical Biography. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley-Blackwell, 1998.

Web sites

The Goethe Society. Retrieved March 3, 2007, from http://www.goethesociety.org