World Literature

Robert Graves

BORN: 1895, London, England

DIED: 1985, Majorca, Spain

NATIONALITY: British

GENRE: Fiction, nonfiction, poetry, drama

MAJOR WORKS:

Good-Bye to All That (1929)

I, Claudius (1934)

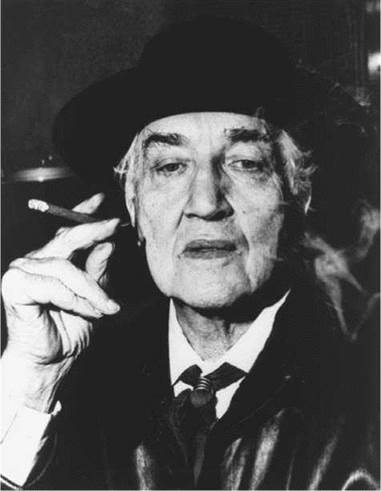

Robert Graves. Graves, Robert, photograph. AP Images.

Overview

Robert Graves is considered one of the most distinctive and lyrical voices in twentieth-century English poetry. Openly dismissive of contemporary poetic fashions and precepts, Graves developed his own poetic theory, principally inspired by ancient mythology and folklore. Although Graves regarded himself as a poet first, he was widely respected for his prose works. He is best known for his World War I autobiography Good-Bye to All That (1929) and for his novel I, Claudius (1934).

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

Family and World War I. Robert von Ranke Graves was born in Wimbledon, England, on July 24, 1895, to Alfred Perceval Graves and his second wife, Amalie (Amy) Elizabeth Sophie von Ranke Graves. His father was an Irish poet, and his mother was a relation of Leopold von Ranke, one of the founding fathers of modern historical studies. Graves won a scholarship to Oxford University in 1913.

Graves left school at the outbreak of World War I and promptly enlisted for military service. World War I began in eastern Europe when the heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, was assassinated in Serbia by a Bosnian terrorist. Subsequent diplomacy failed, and entangling alliances led to war, which soon engulfed nearly the whole of Europe. Great Britain was allied with France and Russia, and, when it entered the war in 1917, the United States, against Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Turkey. Graves was sent to France where trench warfare was commonplace. He saw extensive military action and was injured in the Somme offensive in 1916, one of the biggest battles in the war, with 1.5 million casualties.

Poetry and Good-Bye to All That. While convalescing from war injuries, Graves wrote two volumes of poetry: Over the Brazier (1916) and Fairies and Fusiliers (1918). These poems earned him the reputation as an accomplished ‘‘war poet’’ like fellow war poet Siegfried Sassoon. While still in the army, Graves married and moved to Oxford to begin his university studies. Although Graves failed to finish his degree, he wrote a postgraduate thesis that enabled him to teach English at Cairo University in Egypt.

In 1929, he published Good-Bye to All That, an autobiography that was considered to be one of the best firsthand accounts of World War I. That same year, Graves left his wife for the American poet Laura Riding, who had considerable influence on his poetic development, and moved with her to Majorca, Spain. In Graves’s second volume of collected poems, Poems, 1926-1930, his previous idealized sentimentality is replaced by intensely personal and sad poems that explore the possibilities of salvation and loss through love.

More War and Personal Loss. The Spanish Civil War (a conflict that began in 1936 between republican and nationalist forces for political and military control of the country) forced Graves and Riding to leave Majorca in 1939. They traveled to the United States, where Riding became involved with and eventually married an American poet, Schuyler Jackson. Distraught, Graves returned to England and began a relationship with Beryl Hodge.

In the 1940s, after his break with Riding, Graves formulated his personal mythology of the White Goddess, inspired by late nineteenth-century studies of femaleheaded societies and goddess cults. The White Goddess: A Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth (1948) is Graves’s search for his muse through the mythology of Europe.

Historical Novels. In the 1930s and 1940s, Graves supported himself financially by writing historical novels that earned him both popular and critical acclaim. His most memorable works of fiction are the popular historical novels I, Claudius (1934) and Claudius the God and His Wife Messalina (1934). These works document the political intrigue and moral corruption of the Roman Empire’s waning years in terms that suggest parallels with twentieth-century civilization. In Count Belisarius (1938), Graves displays his knowledge of the early Middle Ages, while in Sergeant Lamb of the Ninth (1940) and Proceed, Sergeant Lamb (1940), he demonstrates his understanding of military tactics through his depiction of a British soldier at the time of the American Revolution.

In The Story of Marie Powell: Wife to Mr. Milton (1943), Graves attempts to debunk John Milton’s reputation as a great poet by viewing him through the eyes of his first wife, who is portrayed as Milton’s intellectual equal. The Golden Fleece (1944) is a retelling of the legend of Jason and the Argonauts and is notable for its inclusion of poems and mythology informed by the White Goddess. King Jesus (1946) is a controversial novel in which Graves postulates that Jesus Christ survived the crucifixion. In Watch the North Wind Rise (1949), Graves presents a futuristic utopia that worships a goddess and follows customary rituals.

From 1961 to 1966, Graves lectured periodically at Oxford University in his capacity as professor of poetry, and in 1968 he received the Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry. Throughout his career he published and revised numerous editions of his Collected Poems, and continued to publish original collections through the 1970s, including Timeless Meeting (1973). Graves died in Majorca in 1985 at the age of ninety.

Graves writes in a traditional style—he employs short-line verse structure and idiosyncratic meters; however, the content of his work is filled with ironies, combining humor with emotional intensity. Graves’s early volumes of poetry, like those of his contemporaries, deal with natural beauty and country pleasures in addition to the consequences of World War I. Because of his experiences in World War I, Graves had a lifelong preoccupation with the subject of war.

War Theme and Influence. Neither Good-Bye to All That nor his war poems minimize the traumatic effect that the war had on Graves, but they avoid the nostalgia and bitterness of many contemporary works dealing with similar experiences. Paul Fussell sees Good-Bye to All That as less memoir than comedy of manners, following in the tradition of Elizabethan playwright Ben Jonson. The ironic and farcical elements of Graves’s treatment of war, Fussell argues, had a strong influence on both English writer Evelyn Waugh and American writer Joseph Heller.

Poetic Muse. In the 1940s, Graves formulated his personal mythology of the White Goddess. Inspired by late nineteenth-century studies of matriarchal societies and goddess cults, Graves asserts in The White Goddess: A Historical Grammar of Poetic Myth (1948) that ‘‘the true poet’’ receives inspiration from a female Muse, ‘‘the cruel, capricious, incontinent White Goddess,’’ and seeks to be destroyed by her. Central to this mythology is the ancient Near Eastern story of Attis, the mortal male who becomes the consort of the goddess Cybele after she has driven him to madness and suicide. The yearly death and resurrection of Attis is a metaphor of the natural seasonal cycle to which Graves alludes in such poems as ‘‘To Juan at the Winter Solstice,’’ ‘‘Theseus and Ariadne,’’ and ‘‘The Sirens’ Welcome to Cronos.’’ Randall Jarrell has written of these poems that they ‘‘are different from anything else in English; their whole meaning and texture and motion are different from anything we could have expected from Graves or fTom anybody else.’’

For Graves, it was much more than that. He became the Goddess’s acolyte and devotee, her high priest. In poet Alistair Reid’s words, ‘‘Only he could interpret her wishes, her commands.’’ Writing The White Goddess gave order to Graves’s deepest convictions and restored a sanctity to poetry he felt had been lost by rejecting myth for reason. She was also his muse, and his devotion to her was such that much of his last work from the 1960s on was given over to love poetry, inspired at the moment by whichever young woman had stepped into the muse role (there were at least four).

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Graves's famous contemporaries include:

Harold Gillies (1882-1960): New Zealander surgeon and one of the founders of reconstructive, or plastic, surgery. He developed his techniques by providing facial repairs to injured soldiers during World Wars I and II.

Margaret Mitchell (1900-1949): American writer and author of Gone with the Wind (1936), a historical romance set during the American Civil War and Reconstruction period. The novel won the Pulitzer Prize for Literature in 1937.

Wilfred Owen (1893-1918): British poet, killed in action one week before the end of World War I; well-known for his bitter war poems ''Anthem for Doomed Youth'' (1917) and the posthumously published ''Dulce et Decorum Est'' (1920).

Pablo Picasso (1881-1973): Spanish artist who helped create the cubist movement. His famous painting Guernica (1937) expresses his anguish over the bombing of the Spanish town of Guernica by the Nazis during the Spanish Civil War.

Siegfried Sassoon (1886-1967): English poet and novelist and friend of Graves during World War I. His poetry depicts the brutality of war rather than a more "patriotic," idealized view.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

War has been a common theme in literature throughout time. Here are some works that address various aspects of the war experience:

All Quiet on the Western Front (1929), a novel by Erich Maria Remarque. This novel, based on the author's own experience, tells of the German soldiers' experiences during World War I and their difficulty reintegrating into society after the war.

The Bridges at Toko-Ri (1953), a novel by James Michener. This novel, which follows a group of American fighter pilots in the Korean War, is based on a true story.

Iliad (c. ninth or eighth century B.C.E.), an epic poem by Homer. This Greek epic poem tells of events during the tenth and last year of the Trojan War, between the Greeks and the Trojans.

The Return of the Soldier (1918), a novel by Rebecca West. This novel tells the story of a British soldier suffering from what was then known as ''shell shock'' (today called post-traumatic stress disorder) and his struggles to return to civilian society after World War I.

Under Fire (1917), a novel by Henri Barbusse. Written by a soldier and based on his own experiences in World War I, this novel was published during the war and was one of the first war novels. It tells of French soldiers fighting the Germans in occupied France.

Works in Critical Context

Robert Graves has a secure reputation as a prose writer. Good-Bye to All That is considered one of the finest books to come out of World War I, and many commentators praise the imaginative re-creation of imperial Rome in I, Claudius.

Poetry. Graves wished to be remembered as a poet. Critics acknowledge his technical mastery and lyrical intensity, but there is a divergence of opinion. Many have claimed that the work of poets such as W. B. Yeats and T. S. Eliot, whom Graves dismissed, is more enduring and memorable than that of Graves. Other critics, however, have argued that Graves’s independence from twentieth-century trends had a lasting impact on younger English poets. In 1962, W. H. Auden went as far as to assert that Graves was England’s ‘‘greatest living poet.’’ Having founded no school and with few direct disciples, Graves, through his mythologically inspired love poetry, occupies a unique position among twentieth- century poets writing in English. As scholar John Carey wrote in Graves’s obituary, ‘‘He had a mind like an alchemist’s laboratory: everything that got into it came out new, weird and gleaming.’’

Seconding Carey’s view of Graves’s importance as a poet, Randall Jarrell, in The Third Book of Criticism, concludes that ‘‘Graves is a poet of varied and consistent excellence. He has written scores, almost hundreds, of poems that are completely realized, different from one another or from the poems of any other poet. His poems have to an extraordinary degree the feeling of one man’s world.’’

Responses to Literature

1. After reading Good-Bye to All That, write a brief analysis commenting on Graves’s tone. Describe your emotions toward his war experiences in a paper.

2. Read several of Graves’s poems about war. Hold a class discussion stating whether the images and themes are relevant today. Would a soldier today hold the same views as Graves? Why or why not?

3. Graves is known for historical novels. Think of a period in history or a specific historical event that interests you and write two or three paragraphs about how you could develop the event into a historical novel. Whose point of view would you take?

4. Using your library’s resources and the Internet, research the mythic figure of the White Goddess, then read Graves’s poem by the same name. Hold a group discussion as to why you think Graves devoted an entire book to his own mythology of the White Goddess.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Carter, D. N. G. Robert Graves: The Lasting Poetic Achievement. New York: Barnes & Noble, 1989.

Day, Douglas. Swifter than Reason: The Poetry and Criticism of Robert Graves. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1963.

Fussell, Paul. The Great War and Modern Memory. New York: Oxford University Press, 1975.

Graves, Robert. Oxford Addresses on Poetry. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1962.

Hoffman, D. G. Barbarous Knowledge. New York: Oxford University Press, 1967.

Jarrell, Randall. ‘‘Graves and the White Goddess.’’ In The Third Book of Criticism. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1969.

Keane, Patrick J. A Wild Civility: Interactions in the Poetry and Thought of Robert Graves. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1980.

Seymour, Miranda. Robert Graves: A Life on the Edge. New York: Henry Holt, 1995.

Periodicals

Spears, Monroe K. ‘‘The Latest Graves: Poet and Private Eye.’’ Sewanee Review 73 (1965): 660-78.

Steiner, George. ‘‘The Genius ofRobert Graves.’’ Kenyon Review 22 (1960): 340-65.

Web Sites

Fundacio Robert Graves. Ca N’Alluny: The House of Robert Graves [Majorca]. Retrieved April 25, 2008, from http://www.fundaciorobertgraves.com/index.php?eng.

The Robert Graves Society. Retrieved April 25, 2008, from http://www.gravesiana.org/.

St. John’s College Robert Graves Trust. Retrieved April 25, 2008, from http://www.robertgraves.org/.