World Literature

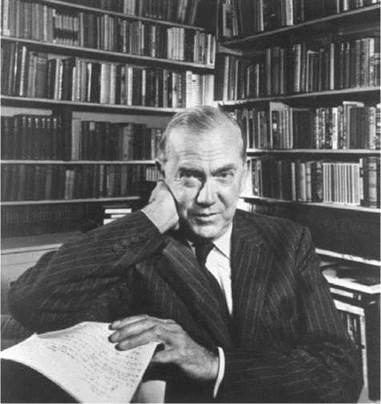

Graham Greene

BORN: 1904, Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire, England

DIED: 1991, Vevey, Switzerland

NATIONALITY: British

GENRE: Travel, nonfiction, fiction

MAJOR WORKS:

The Power and the Glory (1940)

The Heart of the Matter (1948)

The End of the Affair (1951)

The Quiet American (1955)

Ways of Escape (1980)

Graham Greene. Greene, Graham, 1969, photograph. AP Images.

Overview

Graham Greene’s life and literature were played out on a global stage; he traveled widely and wrote works set in locales as disparate as Hanoi and Havana, Liberia and Lithuania, Mexico and Malaysia. His works focused on the borders and conflicts between the European world and the ‘‘other’’ world abroad. During Greene’s lifetime— which spanned two world wars and the advent of the nuclear age—he documented the changes that affected both strong empires and struggling nations.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

A Restless Youth. Born in Berkhamsted, England, in 1904, Greene as a child was a passionate reader of books. His father was headmaster of a local school, and his mother was a first cousin of noted author Robert Louis stevenson.

Greene entered his father’s school in 1915 and left in 1921, when he was seventeen. Greene continued his education at Oxford, where he received a BA from Balliol College in 1925. His restlessness and sense of adventure, however, had already taken hold. While still a student, he made a long walking trip in Ireland, and, in the same year that he took his degree at oxford, his first book was published: a collection of poetry, Babbling April, which critics saw as imitative.

Greene met his future wife, Vivien Dayrell-Browning, shortly before leaving Oxford in 1925, and he began an intense courtship that precipitated his conversion to her religion, Catholicism, a year before their marriage in 1927. This conversion proved to be more than a matter of expedience. Greene’s Catholicism deeply influenced his work. Many of his novels, including Brighton Rock (1938), The Power and the Glory, The End of the Affair (1951), and others, center around religious faith and morality.

Writer and Spy. Greene held jobs at the British American Tobacco Company and the Nottingham Journal (both of which he found tedious) before landing a subeditor’s position at the Times of London. At the Times he advanced steadily from 1926 until the success of his first novel in 1929, at which point he became a full-time writer. Greene also wrote film criticism for Night and Day and the Spectator in the 1930s.

Greene went to Mexico in the late winter of 1937-1938. He had been commissioned by a London publishing house, Longmans, Green, to study the plight of the Mexican Catholic Church, which had for over a decade been engaged in a running feud with the revolutionary government—the government having decided to enforce a clause in the revolutionary constitution that would prevent clergymen from voting or commenting on public affairs. His experiences in Mexico inspired one of his greatest novels, The Power and the Glory. Then, during World War II, Greene again found himself in the thick of things, if also on the periphery; he worked several months with the Ministry of Information and later served with the British Foreign Office in Sierra Leone and Nigeria, experiences that inform his spy thrillers and adventure stories, including the 1948 novel The Heart of the Matter.

Success in Print and on Screen. Greene and his wife permanently separated in 1947 after she discovered he had a mistress, an American woman named Catherine Walston. Though his private life was troubled, Greene’s career was taking flight. He wrote the screenplay for director Orson Welles’s classic film noir The Third Man, which won the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival in 1949. Greene’s affair with Walston inspired his 1950 novel The End of the Affair (in fact, the novel was dedicated to her). This acclaimed work was adapted for film in 1955 and again in 1999.

Prescient Novels of International Intrigue. World travel was an integral part of Greene’s life and work. His impressions and experiences during his trips, recorded in his nonfiction, contributed to the authenticity of detail and setting in his novels. Greene traveled to Cuba, the Belgian Congo, Russia, Brazil, Tunisia, Romania, East Germany, and Haiti.

Greene’s increasingly international political enthusiasms provided the background to many of his postwar novels, from The Quiet American (1955), set in Vietnam, to The Human Factor (1978), which explains Cold War espionage. The Quiet American, in particular, offers a realistic picture of how American involvement in the French war to retain control over what was at the time the French colony of Indochina (and what is now called Vietnam) might eventually lead to a full-scale American military commitment in the region. Indeed it did: within ten years America found itself increasingly involved in what became the Vietnam War.

Greene’s 1958 novel Our Man in Havana is a comic spy story about British intelligence agents working to uncover information on a secret Cuban military installation. The novels seems in some ways to predict the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962.

A Citizen of the World Dies in Switzerland. In the 1960s and 1970s Greene’s popularity continued to grow with the success of such works of fiction as The Comedians (1966), Travels with My Aunt: A Novel (1969), and The Honorary Consul (1973). Although he also produced two volumes of memoirs, A Sort ofLife in 1971 and Ways ofEscape in 1980, Greene undertook no further travel narratives as such, but he did write one extended ‘‘biography-travel book escapist yarn memoir,’’ as J. D. Reed, the reviewer for Time magazine, jokingly called it. Published in 1984, Getting to Know the General, Greene’s account of his friendship with Panamanian strongman Omar Torrijos, once again took Greene to the borderland between privilege and squalor, and idealism and cynicism that he had encountered in West Africa and Mexico.

Greene died in Vevey, Switzerland, on April 3, 1991.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Greene's famous contemporaries include:

Robert Graves (1895-1985): an English poet, novelist, and scholar best known for his First World War memoir and his historical fiction.

Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961): an American novelist and journalist whose economical writing style had a significant influence on twentieth-century fiction.

Evelyn Waugh (1903-1966): an English writer best known for his satirical novels, he was widely popular with both readers and critics.

W. H. Auden (1907-1973): an Anglo-American poet, widely regarded as one of the greatest writers of the twentieth century because of his stylistic and technical achievements along with his engagement with moral and political issues.

Anthony Burgess (1917-1993): a British novelist, critic, and composer who launched his career with novels exploring the dying days of the British Empire.

Fidel Castro (1926-): Castro led the Cuban Revolution and ruled the country from 1959 until 2008.

Orson Welles (1915-1985): an American director, writer, actor, and producer. His film Citizen Kane, which won two Academy Awards, is widely considered one of the best films ever made.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Greene's protagonists typically struggle to emerge from the darkness of human suffering into the light of redemption. This redemption is usually preceded by an instance of felix culpa— the ''fortunate fall'' that strips the characters of human pride, enabling them to perceive God's grace. Here are some other works that consider the theme of the fortunate fall:

Paradise Lost (1667), an epic poem by John Milton. This work, Milton's effort to ''justify the works of God to man,'' retells the biblical story of Adam and Eve's temptation by Satan and subsequent expulsion from the Garden of Eden.

The Marble Faun (1860), a novel by Nathaniel Hawthorne. This novel is an unusual romance that explores the idea of guilt and the Fall of Man by focusing on the transformations of four characters living in Italy.

The Fortunate Fall (1996), a science-fiction novel by Raphael Carter. This novel deals with the consequences of a highly computerized and networked society.

Works in Literary Context

Greene’s work is as paradoxical as the man himself. He is repeatedly ranked among the great serious novelists of the twentieth century, yet his books have had enormous success in mass culture as well. He is one of the twentieth-century novelists most frequently and successfully adapted for film. Yet, in spite of its modern cinematic nature, his prose owes virtually nothing to the modern and the experimental, and in fact has more in common with the best nineteenth-century models. Greene more than any modern writer has mixed genres, so that his ‘‘entertainments’’ often seem relatively serious and his religious and political books sometimes resemble spy or mystery stories.

The Thoughtful Thriller. Greene frequently wrote what might be termed ‘‘thoughtful thrillers.’’ While The Quiet American, The Heart of the Matter, and The Human Factor are all gripping in their various ways, they also are all thought-provoking, prompting readers to consider more deeply the meanings and dynamics of international politics, and the intersections between the personal and the political. The reader of Greene’s political thrillers may leave satisfied that the roller-coaster of espionage and drama has arrived at a safe conclusion (sometimes), but he or she also leaves more concerned than ever about the state of the world itself. What, Greene challenges us to ask long after we have put down the book, is really going on—around us and within us?

Works in Critical Context

Critical response to Greene’s novels has been favorable, with several exceptions. Some critics fault Greene’s prose style for not developing beyond straightforward journalism, for avoiding the experimental modes of twentieth- century literature. Other naysayers argue that Greene’s characters are little more than two-dimensional vehicles for Greene’s Catholic ideology. Most commentators, however, would agree with Richard Hoggart’s assessment: ‘‘In Greene’s novels we do not ‘explore experience’; we meet Graham Greene. We enter continual reservations about what is being done to experience, but we find the novels up to a point arresting because they are forceful, melodramatic presentations of an obsessed and imaginative personality.’’ When he died in 1991, Greene was eulogized widely as one of the most important novelists of the twentieth century.

The Quiet American. Responses to The Quiet American have frequently focused on the 1958 Joseph Mankiewicz film adaptation, an important cinematic effort, but also limited because Cold War politics had prevented the filmmaker from fully following Greene’s critical attitudes toward United States involvement in Vietnam. For instance, Kevin Lewis notes that ‘‘although the 1958 film is artistically compromised, full of evasions and half-truths, it is fascinating as a barometer of liberal American political opinion during the height of the Cold War.’’ In a similar vein, film critic Paula Willoquet-Maricondi considers the film adaptation's influence on later Hollywood treatments of Vietnam, suggesting that in Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket (1987), for example, ‘‘We are taken back to the origins of American involvement in Vietnam evoked in The Quiet American and thus to the myths that motivated that involvement.'' For all that, some critics do still focus their attentions on the book itself—even then, though, the tendency is to treat it as a sort of history-prophecy combination, even more than as a piece of literature. In the words of Peter Mclnerny, ‘‘Readers have recognized that the novel is a visionary or proleptic history of what would happen to Americans in Vietnam. ‘He had always understood what was going to happen there,' Gloria Emerson writes in her account of an interview with Greene, ‘and in that small and quiet novel, told us nearly everything.'''

Whatever his ultimate ranking as an artist, Greene will surely be remembered as one of the most articulate spokesmen of his time. Greene has called his method journalistic, but he has been a journalist of political motive and religious doubt, of alienation and commitment, recording the lives of both the underground agent and the teenage tough. His work, a history of our paradoxical and turbulent times, fathers the principle of moral uncertainty that underlies so much of modern spy and political fiction: the individual in conflict with himself.

Responses to Literature

1. Greene explored the borders between the European world and the world of its former colonies, exploring realms that had been brought closer together during his lifetime. With the Internet and e-mail, these worlds are even closer today, and travel to distant locations can be accomplished while maintaining much greater contact with the world back home. Do you think the kinds of experiences Greene’s characters had would be different in today’s world? Are the kinds of novels and travel books that Greene wrote a relic of the past, or is there a place for this kind of writing in today’s world?

2. Greene has been criticized for using his writings to further Catholic ideology. Does Catholicism play a central role in his works? If so, does it make them less or more worthy of study and reflection, or does it have no effect? Why?

3. Greene wrote about the modern world in prose that was neither modern nor experimental and has been likened to the style of nineteenth-century writers. What are the strengths of this choice of prose style, and what aspects of modern life was Greene unable to convey adequately because he chose to use a style borrowed from a previous century?

4. Much of Greene’s work was based on his personal travels to exotic and faraway lands, but he was also able to turn his journeys closer to home into widely read travel essays. Write an essay about one of your own journeys, even one that did not take you far from home.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Adamson, Judith. Graham Greene: The Dangerous Edge: Where Art and Politics Meet. New York: St. Martin’s, 1990.

Boardman, Gwenn R. Graham Greene: The Aesthetics of Exploration. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1971.

Duran, Leopoldo. Graham Greene: Friend and Brother. Trans. Evan Cameron. London: HarperCollins, 1994.

Meyers, Jeffrey. ‘‘Graham Greene: The Decline of the Colonial Novel.’’ In Fiction and the Colonial Experience. Totowa, N.J.: Rowman & Littlefield, 1973.

________. ‘‘Greene’s Travel Books.’’ In Graham Greene: A Revaluation; New Essays. New York: St. Martin’s, 1990.

Mockler, Anthony. Graham Greene: Three Lives. New York: Hunter Mackay, 1995.

Shelden, Michael. Graham Greene: The Enemy Within. New York: Random House, 1995.

Sherry, Norman. The Life of Graham Greene. 2 vols. New York: Viking, 1989-1994.

Spurling, John. Graham Greene London: Methuen, 1983.