World Literature

Ayi Kwei Armah

BORN: 1939, Takoradi, Gold Coast (now Ghana)

NATIONALITY: Ghanaian, Senegalese

GENRE: Fiction

MAJOR WORKS:

The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born (1968)

Fragments (1971)

Two Thousand Seasons (1973)

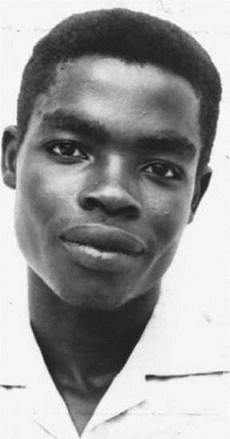

Ayi Kwei Armah. Writer Pictures / drr.net

Overview

Ayi Kwei Armah is perhaps the most versatile, innovative, and provocative of the younger generation of postwar African novelists, and like all authors who express extreme views in their books, he has become a controversial figure in both African and Western critical circles. The controversy has centered exclusively on the works and not on the man, about whom extremely little is known.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

Childhood Coincided with Ghanaian Independence. Only twice has Armah broken his rule of silence about himself and his work, and it is to these two essays that Western critics owe nearly all of their biographical information about him.

Armah was born in 1939 in the coastal city of Takoradi, a seaport of the then-British colony of the Gold Coast. During World War II, citizens of the Gold Coast participated in the war effort, often under the auspices of the British military. In the postwar period, veterans and others who lived in the Gold Coast realized they had just fought a war against oppression and wanted to gain their own freedom. The colony was able to achieve self-government in 1951, and formal independence in 1957 when it became Ghana.

The first twenty years of Armah’s life coincided with the development of his country, through a mixture of political negotiation and violent struggle, into Africa’s first independent state. To complete his secondary education, Armah studied at Achimota College in Ghana. He then worked as a Radio Ghana scriptwriter, reporter, and announcer, before winning a scholarship to study in the United States in 1959, two years after Ghanaian independence.

Left Harvard to Trek Across the World. Armah spent one year at a preparatory school in Massachusetts before entering Harvard University in 1960, but left college in 1963 before completing his courses and examinations. Influenced by the growing number of African revolutionary movements and perhaps by the American civil rights movement as well, Armah set out on a seven- thousand-mile trip over four continents to pursue a truly ‘‘creative existence.’’ The experience led to a physical and mental breakdown.

First Novel an International Success. Returning to the United States, Armah went back to Harvard, completed his BA, and later earned an MFA at Columbia University. He spent 1967 to 1968 in Paris, where he worked as the editor of Jeune Afrique. In 1968, Armah published The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born, a novel often described as existentialist. It burst upon the international literary scene and quickly became a classic of African fiction. The protagonist, simply known as ‘‘the man,’’ is a railway clerk in Ghana during the regime of Kwame Nkrumah, the African leader who took power when Ghana gained independence from Britain.

American Experiences Informed Next Two Novels. After again living in the United States and working at the University of Massachusetts, Armah returned to Africa in 1970, where he continued to write while holding teaching, scriptwriting, translating, and editing jobs. He first lived in Tanzania, where he taught African literature and creative writing. From 1972 to 1976, he was teaching the same subjects in Lesotho. During this period, he wrote a number of important novels as many independent countries in Africa continued to struggle to define themselves as political entities.

Like ‘‘the man,’’ the protagonists of Armah’s next two novels are alienated in their respective societies and, like Armah, they have studied in the United States. Fragments (1971) tells the story of a ‘‘been-to,’’ (someone who has been to the United States) who is hounded into madness by his family because of what he brings back from his stay in America. It is not the instant return of material possessions and prestige that they expect of him, but a moral idealism that interferes with the selfish materialism they have taken over from Western culture.

Why Are We So Blest? (1972) is the story of Modin, an African student studying at Harvard. He leaves school and returns to Africa with his white girlfriend Aimee to participate in a revolutionary struggle. Modin is ultimately destroyed in Armah’s complex tale, which explores, among other things, sexual relationships and the hierarchy of race as Modin is subjugated and sped to destruction by Aimee.

Turned to “Historical” Novels. In Two Thousand Seasons (1973), however, Armah began to portray entire African communities in a historical context—and in their struggles, these communities would succeed. The novel, which calls for the reclamation of Africa’s traditional values, covers one thousand years of African history. The Healers (1978), Armah’s next novel, is the story of a young protagonist, Densu, who studies to become a healer at a time when Africa is being ravaged by a virulent plague of non-African origin.

Wrote from Senegal. Since the publication of this novel, Armah has advocated the establishment of an African publishing industry and of an African literature in African languages, rather than European languages. Armah returned to the United States to teach at the University of Wisconsin in 1979. He later went back to Africa and made his home in Dakar, Senegal, where he focused primarily on his writing.

In 1995 came the novel Osiris Rising, which was published only in Senegal, as was Kmt: In the House of Life (2002). Armah continues to live and work in Senegal.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Armah's famous contemporaries include:

Muammar al-Gaddafi (1942- ): Libyan leader and advocate of pan-Africanism and pan-Arabism; widely respected throughout Africa for the stability of his rule, but, until recently, considered by the West to be a sponsor of terrorism.

Mariama Ba (1929-1981): Muslim Senegalese author and feminist; her work exposes the discrimination and imbalance of power that African women experience in daily life.

Breyten Breytenbach (1939- ): White South African poet and advocate for minority rights; he has been exiled and imprisoned for his political views.

Frantz Fanon (1925-1961): Writer and scholar from Martinique, West Indies; his works critiquing colonization strongly influenced Armah as well as many anticolonial liberation activists.

Kwame Nkrumah (1909-1972): First prime minister (1952-1966) of Ghana after its independence and influential pan-Africanist, promoting African unity and traditional African values; while he was out of the country, his government was overthrown by a coup.

Works in Literary Context

Influences and “Un-African” Style Armah’s combination of an African background with an American education has made the question of the literary sources of his fiction a difficult one. During the 1970s, many Western critics detected European influences, including that of French existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre, Irish postmodernist Samuel Beckett, French ‘‘nouveau roman’’ pioneer Alain Robbe-Grillet, and innovative French writer Louis- Ferdinand Celine.

In the case of Armah’s third novel, Why Are We So Blest?, black American literature and polemic were added to the list of influences. The divergence of Armah’s visionary, symbolic fictional modes from the realist mainstream of African fiction has provoked charges from African critics, notably Chinua Achebe, that his characterization and style are ‘‘un-African’’ and have more in common with expatriate fiction about Africa written by Europeans than with African writing.

Importance of Ritual and Tradition. However, Armah’s figurative treatment of the intricacies of ritual process gives his work an unexpected and seldom-noticed common ground with work from which his own art has been thought far removed, such as the tradition-oriented early plays of Wole Soyinka, the Nigerian writer, and with the writing of authors who have adopted a hostile critical stance toward him, such as the Ghanaian writer Kofi Awoonor.

African commentators—notably Solomon O. Iyasere and D. S. Izevbaye—who adhere to more inclusive concepts of traditionalism have drawn attention to the connection of The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born both to African fable and to the personifications of the oral tradition, and to Fragments’s striking simulation of the oracular and editing devices of the narrative style of the griots, or traditional oral storytellers.

Reflections of African Society In his first three novels, Armah also wrote about the struggles, alienation, and failures of individuals in contemporary African society. In the Ghana of The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born, for example, filth and excrement are everywhere, serving in the novel as metaphors for the corruption that permeates society. The man, however, resists this corruption and fights the ‘‘gleam’’ that causes almost all Ghanaians to pursue material wealth and power through bribery and other foul deeds. With Two Thousand Seasons and The Healers, Armah turned to more historical African concerns and highlighted the need to return to traditional African culture as a model for the future, something he tried to do in his own influential life and work.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Colonialism is never far from the surface in Armah's novels. Here are some other works that examine colonialism and its effects.

Colonialism and Neo-colonialism (1964), by Jean-Paul Sartre. This classic collection of writings by the French philosopher examines his country's colonization of Algeria, a microcosm of the West's colonization of developing countries.

The Glass Palace (2000), by Amitav Ghosh. This epic novel sweeps from Burma and Malaya from 1885 to the present, tracing the history of colonialism across those countries.

The Harbor Boys (2006), by Hugo Hamilton. This coming-of-age memoir tells of the author's struggle to define himself in 1960s Dublin, Ireland, as the son of a German mother and a vehemently anti-English Irish father.

In My Father's House (1993), by Kwame Anthony Appiah. This book of essays by the Ghanaian philosopher examines modern African identity, cultural assumptions, and postcolonial African culture.

The Open Sore of a Continent (1997), by Wole Soyinka. This nonfiction book by the Nobel Prize-winning Nigerian writer examines the crisis in Nigeria brought on by its governing dictatorship.

Works in Critical Context

While Armah is considered one of Africa’s leading prose stylists writing in English, his works have met with a somewhat mixed critical reaction, though many reviewers have praised his stylistic innovations. The author is usually appreciated for the strength of his convictions and desire to promote the improvement of the African continent and those who live there as well.

Early Works Lauded by Critics Critics generally praised Armah’s first three works, especially The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born; many compared Armah’s writing ability with that of such celebrated Western writers as James Joyce and Joseph Conrad. Charles R. Larson, in The Emergence of African Fiction, describes the book as ‘‘a novel which burns with passion and tension, with a fire so strongly kindled that in every word and every sentence one can almost hear and smell the sizzling of the author’s own branded flesh.’’ In the Journal of Commonwealth Literature, James Booth describes it as ‘‘the most powerful work of a novelist of genius.’’ But other critics— notably Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe—accused Armah of portraying Africa in a European manner.

Early critical allegations that there are few ‘‘Africanisms’’ in Armah’s first two novels and that the books do not draw upon Ghanaian settings, speech, or history, have not held up under close investigation, however. These books are so imbued with surviving ritual forms, ceremonial motifs, local mythologies, and residual ancestral beliefs that traditional West African culture is always powerfully, if remotely, present, both in its superior ethical imperatives and its inherent deficiencies.

Mixed Reception for ‘‘Historical’’ Novels. Two Thousand Seasons and The Healers have had a mixed reception. These two historical novels have been widely hailed by African critics as evolving a major new style for African literature. Some Western critics, notably Gerald Moore and Bernth Lindfors, have expressed reservations about them, however, and there seems to be a consensus in the West that they show signs of reduced inspiration and declining artistic achievement. Robert Fraser, on the other hand, has argued that their apparent radical line of departure is really a curve in an arc of continuous development and achievement from the early novels, and he has fewer reservations about the method and manner by which the beautiful ones are finally ‘‘born’’ in Armah’s fiction.

Responses to Literature

1. Armah is known to keep fairly quiet about his personal life and work. Many of his novels, however, draw heavily from his own life experiences as a Ghanaian and as an Ivy League student in the United States. Compare Armah’s novel Fragments with the known details of the author’s life. What elements are taken directly from his own experiences? Which appear to be largely fictional? Why do you think he chose to create a fictional work instead of an autobiography?

2. Armah’s recent novels have only been published in Senegal. Do you think that a writer should always aim to reach as many readers as possible? What are some reasons why a writer might choose to target a smaller audience?

3. Read the excerpt from Armah’s essay ‘‘One Writer’s Education.’’ What does he mean when he calls writing ‘‘the least parasitic option open to me’’?

4. Armah advocates using a common African language as the main language in Africa instead of European languages. Using the Internet and your library’s resources, research Chinua Achebe and Breyten Breytenbach, two African writers who have chosen to write in ‘‘hostile’’ languages in order to reclaim them. Write an essay analyzing their view and contrasting it with Armah’s view. Explain whose view you agree with more, using specific reasons to back up your argument.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Anyidoho, Kofi. ‘‘The Example of Ayi Kwei Armah.’’ In Literature and African Identity. Bayreuth African Studies Series 6. Matieland, South Africa: University of Stellenbosch, 1986.

Brooks, Gwendolyn. ‘‘African Fragment.’’ In Report from Part One. Detroit: Broadside, 1972.

Fraser, Robert. The Novels of Ayi Kwei Armah: A Study in Polemical Fiction. London: Heinemann, 1979.

Gakwandi, Shatto Arthur. The Novel and Contemporary Experience in Africa. London: Heinemann, 1977.

Jackson, Tommie Lee. The Existential Fiction of Ayi Kwei Armah, Albert Camus, and Jean-Paul Sartre. Lanham, Md.: University Press of America, 1996.

Larson, Charles R. The Emergence of African Fiction. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1972.

Lazarus, Neil. Resistance in Postcolonial African Fiction. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1990.

Oforiwaa, Yaa, and Addae Akili. The Wisdom of the Ages: Themes and Essences of Truth, Love, Struggle, and High-Culture in the Works of Ayi Kwei Armah and Kiarri T-H. Cheatwood. Richmond, Va.: Native Sun, 1995.

Yankson, Kofi E. Ayi Kwei Armah’s Novels. Accra, Ghana: 1994.

Periodicals

Amuta, Chidi. ‘‘Ayi Kwei Armah and the Mythopoesis of Mental Decolonisation.’’ Ufahamu 10 (Spring 1981): 44-56.

Anyidoho, Kofi. ‘‘The Contemporary African Artist in Armah’s Novels.’’ World Literature Written in English 21 (Autumn 1982): 67-76.

Bishop, Rand. ‘‘The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born: Armah’s Five Novels.’’ World Literature Written in English 21 (Autumn 1982): 531-37.

Lindfors, Bernth. ‘‘Armah’s Histories.’’ African Literature Today 11 (1980): 85-96.

Oluoch-Olunya, Garnette. ‘‘A Confiscated History.’’ East African (February 28, 2005).