World Literature

A. A. Milne

BORN: 1882, London, England

DIED: 1956, Sussex, England

NATIONALITY: British

GENRE: Fiction, poetry, drama

MAJOR WORKS:

When We Were Very Young (1924)

Winnie-the-Pooh (1926)

Now We Are Six (1927)

The House at Pooh Corner (1928)

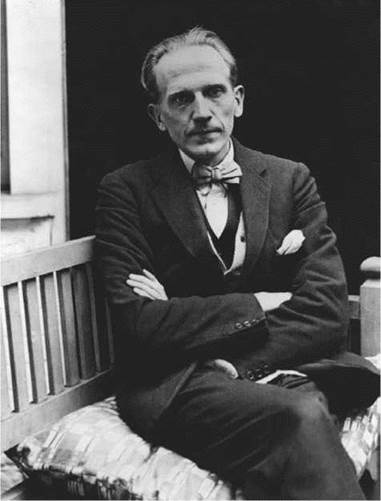

A. A. Milne. Milne, A. A., photograph.

Overview

British author A. A. Milne wrote plays, essays, novels, and light verse for adults; however, his most critically acclaimed works were his ‘‘four trifles for the young,’’ as he called them, his childrens’s tales and poems, some of which featured his best-known literary creation, Winnie-the-Pooh. Milne has been praised for his accurate and sympathetic observations of children’s behavior, his wit, and his skill with language, especially wordplay and dialogue.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

Family and Early Life. Alan Alexander Milne was born January 18, 1882, in London, England, to John Vine Milne, a school headmaster, and Sarah Maria Heginbotham Milne. He attended Cambridge University, where he edited the undergraduate paper The Granta. Upon completion of his degree in mathematics in 1903, he moved to London and worked as a freelance journalist. In 1906, he accepted an assistant editorship with the magazine Punch, where he worked for eight years, contributing humorous essays and verse. Milne married Dorothy de Selincourt in 1913 and their son, Christopher Robin, was born in 1920.

First Plays and Mystery Novels. In 1914, the start of World War I, he joined the army. Milne had already published three collections of essays from Punch and was becoming well-known as a humorist. His work as a dramatist began during his military service. His first play appeared in 1917, and his one unqualified success in the theater, Mr. Pim Passes By, was completed and produced in 1919. He also wrote two mystery novels; Red House Mystery (1921) is considered a classic in the genre and helped establish the conventions of British detective fiction between World War I and World War II. In an introduction he wrote for the 1926 reprint, Milne says he set four goals for himself: The mystery should be written in simple English; there must be no love interest; the detective must have a confidant with whom to discuss the case, clue by clue; and, most important, the detective must be an amateur.

When We Were Very Young. Occasional poems written for his son Christopher quickly grew into the collections When We Were Very Young (1924) and Now We Are Six (1927). When We Were Very Young was immediately recognized as a new kind of children’s book, one that moved away from fairytales and the overly didactic literature of the time and portrayed children realistically in an enjoyable, stylish manner. Throughout the poems, the child questions the power that adults command.

When We Were Very Young paved the way for Winnie-the-Pooh (1926) and helped to immortalize the name Christopher Robin, to the embarrassment of the actual Christopher Robin Milne, who spent much of his life attempting to disentangle himself from the semibiographical, fictional character.

Winnie-the-Pooh. When We Were Very Young and Now We Are Six were successful with both critics and the public, but they were soon surpassed by the stories in Winnie-the-Pooh (1926) and The House at Pooh Corner (1928). Milne wrote these works after observing the interaction between Christopher and his mother and the boy’s beloved stuffed animals. Both Milne’s verses and the Pooh stories became a publishing phenomenon.

Much of the delight of Winnie-the-Pooh comes from the illustrations by E. H. Shepard. Because Milne had acknowledged that part of the success of When We Were Very Young resulted from Shepard’s illustrations, Shepard was asked to illustrate Winnie-the-Pooh. The original illustrations were black and white. When Shepard was in his eighties, he undertook the task of coloring the original illustrations.

Later Life. Milne continued to write plays following the publication of his children’s books, but publishers remained more interested in his work in the latter genre than in adult literature. He traveled throughout the United States in the fall of 1931 and continued writing mostly unnoticed books and plays until 1952, the year he suffered a stroke. He died January 31, 1956, at his home in Sussex, England.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Milne's famous contemporaries include:

J. M. Barrie (1860-1937): Scottish novelist and playwright, best known for his children's book Peter Pan. A friend of Milne, Barrie helped get Milne's first play produced.

Irene Joliot-Curie (1897-1956): French chemist and daughter of dual Nobel Prize-winning scientist Marie Curie who, with her husband, was awarded the 1935 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of artificial radioactivity.

J. Robert Oppenheimer (1904-1967): As an American physicist, Oppenheimer became the director of the Manhattan Project during World War II, which developed the first nuclear weapons.

Dorothy Sayers (1893-1957): British writer and mystery novelist. Sayers is well-known for her mysteries featuring Lord Peter Wimsey, set in England between World War I and World War II.

P. G. Wodehouse (1881-1975): British writer and lyricist. Wodehouse is characterized by his humorous short stories featuring the bumbling aristocrat Bertie Wooster and his long-suffering butler Jeeves.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

A. A. Milne's books came at the end of what has been called the ''Golden Age'' of British and American children's literature, from 1865 to 1928. Children's books in this period focused on playfulness and the power of the imagination. Here are some other childrens's works from this period:

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865), by Lewis Carroll. This work ushered in the Golden Age. It tells the story of Alice, a girl who falls down a rabbit hole, and her surreal adventures that follow.

Five Children and It (1902), by Edith Nesbit. In this story, five siblings come across a sand fairy that grants them one wish per day, with humorously disastrous consequences.

The Tale of Peter Rabbit (1902), by Beatrix Potter. The first of many books Potter wrote featuring animals, this short book tells of the adventures of Peter, a mischievous bunny, in Mr. McGregor's garden.

The Wind in the Willows (1908), by Kenneth Grahame. Later adapted for the stage by Milne, this novel tells the story of four animal friends, notably the boastful Toad.

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), by L. Frank Baum. This novel, made into a famous 1939 movie starring Judy Garland, follows Dorothy, a girl from Kansas, who is caught up in a tornado and deposited in the fantastic land of Oz.

Works in Literary Context

As a poet, A. A. Milne has been compared favorably with such writers as Lewis Carroll, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Walter de la Mare; his poems are distinguished by their variety of form and rhythm. Barbara Novak writes: Often ... they have the kind of nonsense whimsy which is too often lost in expression by and for adults. Thus, in ‘Halfway Down,’ the child sits on a stair which really isn’t anywhere but somewhere else instead. We are reminded here of E. E. Cummings’ use of this sort of expression, though Milne’s poetry differs in that it is not a sophisticated adult use of a child’s manner of expression, but rather, the expression of a poet who has never lost the ability to think, feel, and express as a child.

Humor and Fantasy. Milne’s style of humor is not blatant or overt; in fact, an anonymous literary critic in the October 1912 issue of The Academy once suggested ‘‘his quips and jokes are delicate, requiring the dainty palate for their finest appreciation.’’ Though today’s readers know Milne for his Winnie-the-Pooh character, Milne captured readers of his day with dry wit. He approached humor with subtlety, particularly in works like The Day’s Play (1910). As another anonymous reviewer noted in an October 1910 issue of The Academy, Milne’s ‘‘fantasies’’ derived from some ‘‘capital clowning,’’ the obvious result of his keen eye toward ‘‘comical, topsy-turvy reasoning.’’ Furthermore, Milne’s knack for ‘‘clever rhyming,’’ as well as the way in which he twisted the meaning of ordinary words surprised and delighted turn-of-the-century readers.

Family Inspiration. In contrast to the dark, brooding imagery due to arrive in the twentieth century, the Victorian period was characterized by idealized, domestic images. Unlike his contemporaries (such as Ezra Pound and Aldous Huxley) who, in their art, directly responded to bleak social and political changes, Milne often looked backward to the sentimental Victorian years for artistic inspiration. Milne often acknowledged that he did not have an idyllic childhood, and some critics wonder if that may be the reason for his family focus and domestic satire. Many contemporary critics, like Geoffrey Cocks, relate the strong female characters in Milne’s work to his domineering mother: for example, Countess Belvane in the play Once Upon a Time (1917). These critics see Milne’s ‘‘art as a sublimation of psychological conflict’’ that came from his early years.

Works in Critical Context

Although the critical response to Now We Are Six was generally full of praise, Dorothy Parker, a writer for The New Yorker, expressed distaste. Writing as ‘‘Constant Reader,’’ she stated: ‘‘Of Milne’s recent verse, I speak in a minority amounting to solitude. I think it is affected, commonplace, bad.... And now I must stop to get ready for being ridden out of town on a rail.’’

Several reasons have been given for the popularity of Winnie-the-Pooh. For example, readers and critics alike are drawn to the way in which the book both shows how essential the capacity for friendship is to human life and reveals how essential the ability to overlook the faults of one’s friends is to achieving a joyful human existence. Additionally, as Peter Hunt observes, its ‘‘sophisticated writing, the pace, the timing, and the narrative stance all contribut[e] to the comic effect.’’ Furthermore, Ann Thwaite finds that ‘‘part of the strength and charm of the stories comes from the juxtaposition of toy animal and forest.’’

Regarding Milne’s poetic style, Barbara Novak writes: ‘‘We might almost say that Milne’s poetic content falls into two broad categories: one in which the poet expresses something for the child, and one in which he expresses to the child.’’ Certainly, in Winnie-the-Pooh, two voices are frequently heard: Christopher Robin’s words and narratives are intertwined with A. A. Milne’s words and narratives. Milne is purportedly telling Christopher Robin the stories that Christopher Robin remembers, and then does not remember, and then wishes to be told again. Not all critics regard the authorial conferences between Milne and Christopher Robin as flattering to the child, who expresses delight in finding himself elevated into a creative authorial role. Alison Lurie, for instance, regards these dialogues as ‘‘condescending conversations between the author and Christopher Robin.’’

Responses to Literature

1. Think about a mystery novel you have read, or a detective show you have seen on TV. Write an informal, two-page essay explaining whether or not you think they follow the mystery genre guidelines that Milne established.

2. Many crime dramas today have professional investigators or doctors as the detectives. With a classmate, discuss the role of the reader when the person solving the crime has more information than the reader does. Why do you think Milne felt having an ‘‘amateur’’ detective was important?

3. Read some poems from When We Were Very Young or Now We Are Six. Do you agree with Dorothy Parker that they are ‘‘affected’’ and saccharine? Write an essay explaining your views, and argue whether children’s literature should be an escape or should reflect real life.

4. Read some poems from contemporary children’s poet Shel Silverstein, and write an essay comparing and contrasting Milne’s verse with Silverstein’s. Do you think they are both classic children’s authors? Explain your opinion, using specific examples.

5. Using resources from your library or the Internet, look up the original illustrations in The House at Pooh Corner, and compare them to the Disney portrayal. Then think about movies based on books you have read, such as the Harry Potter, Lord of the Rings, or Narnia movies. Write an essay analyzing how seeing someone else’s vision of a book affects your own vision when you reread it. Does it change how you see the characters in your own mind?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Bettelheim, Bruno. The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales. New York: Knopf, 1976.

Carpenter, Humphrey. Secret Gardens: A Study of the Golden Age of Children’s Literature. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1985.

Hunt, Peter. ‘‘A. A. Milne.’’ In Writers for Children. New York: Scribners, 1988.

Lurie, Alison. ‘‘Back to Pooh Corner.’’ In Children’s Literature. Storrs, Conn.: Journal of The Modern Language Association Seminar on Children’s Literature, 1973.

Sale, Roger. Fairy Tales and After. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1978.

Thwaite, Ann. The Brilliant Career of Winnie-the-Pooh: The Definitive History of the Best Bear in All the World. New York: Dutton, 1994.

Toby, Marlene. A. A. Milne, Author of Winnie-the-Pooh. Chicago, Ill.: Children’s Press, 1995.

Wullschleager, Jackie. Inventing Wonderland: The Lives and Fantasies of Lewis Carroll, Edward Lear, J. M. Barrie, Kenneth Grahame, and A. A. Milne. New York: Free Press, 1995.

Periodicals

Chandler, Raymond. ‘‘The Simple Art of Murder.’’ Atlantic Monthly 174 (December 1944): 53-59.

Hutchens, John K. ‘‘Christopher Robin’s Candid Father.’’ New York Herald Tribune Book Review (November 30, 1952): 2.

Mabie, Janet. ‘‘Christopher Robin’s Father.’’ Pictorial Review (February 1932): 2, 26, 30.

Novak, Barbara. ‘‘Milne’s Poem’s: Form and Content.’’ Elementary English 34 (October, 1957): 355-61.

Phillips, Henry Albert. ‘‘The Author of Winnie-the-Pooh.’’ Mentor (December 1928): 49.

Reilly, John M. ‘‘Classic and Hard-Boiled Detective Fiction.’’ Armchair Detective (October 1976): 289ff.