World Literature

Czeslaw Milosz

BORN: 1911, Szetejnie, Lithuania (Russian Empire)

DIED: 2004, Cracow, Poland

NATIONALITY: Polish

GENRE: Poetry, essays, novels

MAJOR WORKS:

The Captive Mind (1953)

Native Realm: A Search for Self-Definition (1959)

A Year of the Hunter (1994)

Roadside Dog (1999)

Milosz’s ABCs (2001)

To Begin Where I Am: Selected Essays (2001)

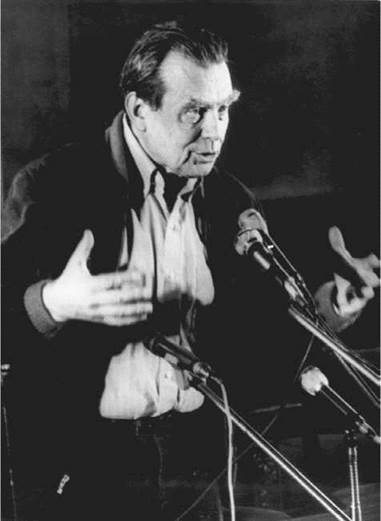

Czeslaw Milosz. Milosz, Czeslaw, University of Jagellonian, Cracow, Poland, 1981, photograph. Keystone / Hulton Archive / Getty Images.

Overview

Pulitzer Prize-winning poet, essayist, novelist, translator, and editor, Czeslaw Milosz (pronounced Mee-wosh) is widely considered Poland's greatest contemporary poet, although he lived in exile from his native land after 1951. Milosz's writings are concerned with humanistic and Christian themes, the problem of good and evil, political philosophy, history, metaphysical speculations, and personal and national identity.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

Birth and Early Life in Poland. Milosz was born on June 30, 1911, in Szetejnie, Lithuania, then a part of tsarist Russia, to Polish-Lithuanian parents. His father, Alexander, was a road engineer and was recruited by the Tsar's army during World War I. Young Milosz and his mother traveled with Alexander on the dangerous bridge building expeditions to which he was dispatched near Russian battle zones.

His family returned to Lithuania in 1918, and Milosz began a strict Roman Catholic education in his hometown of Vilnius, the capital of Polish Lithuania. In his early twenties, he published his frst volume of poems, A Poem on Frozen Time. In 1934 he graduated from the King Stefan Batory University, and in 1936 his second volume of poetry appeared. He earned a scholarship to study at the Alliance Francaise in Paris, where he met up with his distant cousin, Oscar Milosz, a French poet who became his mentor. He recounted his early life in the acclaimed memoir Native Realm.

World War II and the Nazi Occupation of Warsaw. Milosz returned to Poland to work for the Polish State Broadcasting Company. He held this position until the outbreak of World War II. During the Nazi occupation, he stayed in Warsaw where he joined the underground resistance movement. He had an anthology of anti-Nazi poetry, The Invincible Song, published by underground presses in Warsaw, where he also wrote ‘‘The World (A Naive Poem)’’ and the cycle Voices of Poor People.

Warsaw was virtually destroyed by Nazi air force bombing campaigns in response to the Warsaw Uprising of 1944 (an attempt by a Polish insurgent army to force the Germans out of Warsaw). The insurgents had been promised Soviet aid, but it never arrived. Thousands were killed, including most of the young intellectuals and resistance fighters that made up the insurgency. It was speculated that Soviet leader Josef Stalin’s failure to come to their rescue was deliberate: A ruined Warsaw was much easier for him to seize after World War II was over. Milosz survived, and moved to just outside Cracow, whose state publishing house brought out his collected poems in a volume called Rescue.

Ketman and the Failure of the Polish Intelligentsia. At the end of World War II, Milosz worked as a cultural attache for the Polish Communist government, serving in New York and Washington. He left his position with the Polish Foreign Service in 1951 and sought (and received) political asylum in France. Milosz spent ten years in France, where he found himself having difficulty fitting in with the strongly pro-socialist and Communist intellectual community, whose views he considered corrupt or naive. He penned two novels during his time in Paris, Seizure of Power and The Issa Valley. His most famous book, The Captive Mind, was a bitter attack on the manner in which the Polish Communist Party progressively destroyed the independence of the country’s intelligentsia, in essence forcing them to accept and even perpetrate intellectual repression.

Milosz continued to speak out against the way Polish intellectuals had adopted the stance of the Communist leaders. Too often, he believed, his contemporaries would go along with their new masters while secretly believing they could in some way still maintain their own intellectual autonomy. This phenomenon he termed ‘‘Ketman,’’ and in it he saw the downfall of a free intelligentsia in Poland.

Success in the United States. Milosz ultimately felt that the only way to maintain his own intellectual autonomy was in self-imposed exile in the United States. From there, he hoped to contribute to a regeneration of Eastern European culture once the wave of communism had passed. At age fifty, Milosz began a new career as a professor of Slavic languages and literature at the University of California at Berkeley in 1961 (some sources say 1960). He was initially an unknown member of a small department, but eventually he became popular on campus for his courses on Russian author Fyodor Dostoyevsky.

By the 1970s Milosz’s poetry and fiction were increasingly attracting the attention of Western critics. In 1976 he was awarded a Guggenheim fellowship. In 1978 he published the poetry collection Bells in Winter, for which he received the Neustadt International Literature Prize. In 1980 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Back to Polish Roots and a Focus on Roman Catholicism. By this time, many of his poems had become infused with Christian themes connected to Milosz’s Roman Catholic upbringing. There was also a growing sadness and premonition of oncoming death, especially after the death of his wife Janina in 1986. Then, in 1989, the Soviet Union crumbled and the old barriers to travel in Eastern Europe were eased. Milosz was able to return to his roots. After visiting Lithuania in the spring of 1989, Milosz was flooded with memories about his childhood in the Issa River Valley. He was soon able to return to Poland, where his work had been banned for decades. He was greeted with a hero’s welcome and a home in Cracow, courtesy of the Polish people. Despite being afflicted with asthma and declining health, Milosz managed to also release another volume of poetry in 1995, Facing the River. In 1997 he published his correspondence with poet and monk Thomas Merton, a speculative epistolary history of their inner worlds. He followed this with 1998’s Roadside Dog, a collection of poetry.

In April of 2001 Milosz published a book-length poem entitled Treatise on Poetry, translated by Robert Haas. The four parts of the poem deal with turn-of-the- century Europe, Poland between the two world wars, World War II, and the place of the poet in the postwar world. Later that year, a book of essays entitled To Begin Where I Am: The Selected Prose of Czeslaw Milosz made its appearance. These essays chiefly deal with Milosz’s attempts to sustain his religious faith, and with his battle for poetry that is ‘‘on the side of man.’’

Milosz died on August 14, 2004, at his home in Cracow, Poland. He was ninety-three years old.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Milosz's famous contemporaries include:

Robert Haas (1941—): American poet who has served two terms as U.S. Poet Laureate (from 1995-1997) and has contributed greatly to contemporary literature.

Johnny Mercer (1909-1976): American songwriter and singer responsible for many of the popular hits of the mid-1930s and the mid-1950s. The recipient of nineteen Academy Award nominations for his songs for movies, Mercer was also a cofounder of Capitol Records.

Robert Pinsky (1940-): American poet, essayist, literary critic, and translator best known as Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress from 1997 to 2000.

Peter Dale Scott (1929-): Canadian poet and former English professor at the University of California, Berkeley. Scott is best known for his antiwar stance and criticism of U.S. foreign policy dating back to the Vietnam War.

Humphrey Searle (1915-1982): British composer who as a pioneer of serial music also helped to further it by way of his clout as a BBC producer.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Milosz explored in his poetry both the rebirth of Christian belief and the corruption of thought by ideology. His is a frequently difficult and obscure poetry that is burdened by a sense of the oncoming collapse of civilization. Here are a few works by writers who have created similar poetry:

The Waste Land (1922), by T. S. Eliot. A seminal work by the Nobel Prize-winning English poet that explores the disillusionment, spiritual ennui, and casual sexuality of post-World War I European sensibility.

The Darkness and the Light (2001), by Anthony Hecht. A collection of poems by the Nobel Prize-winning American that reflect the technical, intellectual, and emotional horrors of the Holocaust and World War II.

Could Have (1972), by Wislawa Szymborska. A collection of poems by the 1996 Nobel Prize winner, which investigates reality and truth and the burdens within each in witty, subversive tones.

Works in Literary Context

Milosz received a broad education during his studies in Vilnius and he read widely thereafter. Paricularly important in shaping Milosz’s outlook were Russian novelists, poets, and religious thinkers such as Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Leo Tolstoy, Vladimir Sergeevich Solov’ev, and Nikolay Aleksandrovich Berdyayev (and later Lev Shestov). He also read French novels by such writers as Stendahl, Honore de Balzac, and Andre Gide. As far as poetry is concerned, Edgar Allan Poe, Walt Whitman, Robert Browning, and T. S. Eliot were influences once Milosz learned enough English in occupied Warsaw.

The Voice of Experience. In most of his work, Milosz avoided the experimentation with language that characterizes much modern poetry, concentrating more on the clear expression of his ideas. Much of Milosz’s work is strongly emotional and conveys a transcendent spirituality. Critics have commented on the influence of his Roman Catholic background and his fascination with good and evil in both his poetry and his prose. Milosz’s personal experiences, his interest in history and politics, and his aesthetic theories are delineated in his prose works.

For example, his essay collection The Captive Mind studies the effects of totalitarianism on creativity, while Native Realm: A Search for Self-Definition is a lyrical recreation of the landscape and culture of Milosz’s youth. In the nonfiction work The Land of Ulro, Milosz laments the modern emphasis on science and rationality, which he feels has divorced human beings from spiritual and cultural pursuits, by evoking a symbolic wasteland that appears in several of William Blake’s mythological poems. His essay collection Beginning with My Streets: Essays and Recollections—an amalgam of literary criticism, philosophical meditations, and narrative essays—has been praised for its insightful probing of contemporary life, art, and politics.

Milosz’s two novels also combine explorations of twentieth-century world events with autobiographical elements. The Seizure of Power examines the fortunes of intellectuals and artists within a Communist state. Blending journalistic and poetic prose, this work elucidates the relationship between art and ideology and offers vivid descriptions of the Russian occupation of Warsaw following World War II. In The Issa Valley, Milosz evokes the lush river valley where he was raised to explore a young man’s evolving artistic sensibility. The mythical structure of this work explores such dualities as innocence and evil, regeneration and death, and idyllic visions and grim realities.

People and circumstances impacted Milosz’s life, thought, and work, from the Nazi invasion to individuals such as Oscar Milosz, a French poet who became his mentor early on. Likewise, Milosz influenced several readers, students, friends, and fellow faculty. At Berkeley, both students and colleagues—such as Robert Pinsky, Robert Haas, and Peter Dale Scott—participated in the small press printing of several of the poet’s works.

Works in Critical Context

Milosz faced resistance and skepticism in the years following World War II. His work was banned by the Communist regime of his native Poland and some European American intellectuals regarded him with mistrust because he did not fit neatly into a political category. For the past several decades, however, his work has inspired near universal praise from critics and has even earned a widespread popular following.

The Captive Mind. The Captive Mind explains Milosz’s reasons for defecting and examines the life of the artist under a Communist regime. It is, maintains Steve Wasserman in the Los Angeles Times Book Review, a ‘‘brilliant and original study of the totalitarian mentality.’’ Karl Jaspers, in an article for the Saturday Review, describes The Captive Mind as ‘‘a significant historical document and analysis of the highest order.... In astonishing gradations Milosz shows what happens to men subjected simultaneously to constant threat of annihilation and to the promptings of faith in a historical necessity which exerts apparently irresistible force and achieves enormous success. We are presented with a vivid picture of the forms of concealment, of inner transformation, of the sudden bolt to conversion, of the cleavage of man into two.’’

A Year of the Hunter. A Year of the Hunter is a journal Milosz penned between August 1987 and August 1988. Ian Buruma praised the work in the Los Angeles Times Book Review as ‘‘a wonderful addition to [his] other autobiographical writing. The diary form, free- floating, wide-ranging ...is suited to a poet, especially an intellectual poet, like Milosz,’’ allowing for his entries to range from gardening to translating, from communism to Christianity, from past to present. Indeed, as Michael Ignatieff stated in the New York Review of Books, A Year of the Hunter is successful ‘‘because Milosz has not cleaned it up too much. Its randomness is a pleasure.’’

Milosz’s ABCs. A critic for Publishers Weekly noted the following lines from Milosz’s ABCs: ‘‘Man has been given to understand/ that he lives only by the grace of those in power./ Let him therefore busy himself sipping coffee, catching butterflies....’’ The same critic then commented, ‘‘It is difficult to escape the sense that—like butterflies in a dusty case—the scraps of memory affixed here have lost their living glitter.’’

But Edward Hirsch said in The New York Times Book Review that Milosz’s ABCs ‘‘is a source of wonderment and pleasure that at the age of 89, Czeslaw Milosz, arguably the greatest living poet, continues to publish exploratory works of self-definition and commemoration. ... In the end, Milosz’s ABCs is a benedictory text, an alphabetical rescue operation, a testimonial to those who have suffered and gone before us, a hymn to the everlasting marvel and mystery of human existence.’’

Responses to Literature

1. Milosz is quoted as saying, ‘‘Yes I would like to be a poet of the five senses. That’s why I don’t allow myself to become one.’’ What does he mean by this? Do you agree that Milosz is not a poet of the five senses? Why or why not?

2. Identifying with nature allowed Milosz to maintain an identity even in exile. Read the following section from Throughout Our Lands and write about nature and its influence on identity as Milosz sees it. Do you agree that identification with nature helps one maintain their identity? Why or why not?

Wherever you are, you touch the bark of trees testing its roughness different yet familiar, grateful for a rising and a setting sun Wherever you are, you could never be an alien.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Fiut, Aleksander. The Eternal Moment: The Poetry of Czeslaw Milosz. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.

Haas, Robert. Twentieth-Century Pleasures: Prose on Poetry. New York: Ecco Press, 1984.

Mozejko, Edward.Between Anxiety and Hope: The Poetry and Writing of Czeslaw Milosz. Edmonton, Alberta, Can.: University of Alberta Press, 1988.

Periodicals

American Book Review, March 1985, 22.

Books Abroad (Winter 1969; Spring 1970; Winter 1973; Winter 1975).

Book Week (May 9, 1965).

Book World (September 29, 1968).

Boston Globe (October 16, 1987): 91; (August 28, 1994): 62.

Canadian Literature (Spring 1989): 183-184.

Web sites

The Academy of American Poets. Poetry Exhibits: Czeslaw Milosz. Retrieved February 9, 2008, from http://www.poets.org.

Nobel. Czeslaw Milosz. Retrieved February 9, 2008, from http://www.nobel.se/literature/laureates/1980.

Almaz. Czeslaw Milosz. Retrieved February 9, 2008, from http://www.almaz.com/nobel/literature/1980a.html.