World Literature

Yukio Mishima

BORN: 1925, Tokyo, Japan

DIED: 1970, Tokyo, Japan

NATIONALITY: Japanese

GENRE: Fiction, drama

MAJOR WORKS:

Confessions of a Mask (1949)

The Sound of Waves (1954)

The Temple of the Golden Pavilion (1956)

A Misstepping of Virtue (1957)

Death in Midsummer and Other Stories (1966)

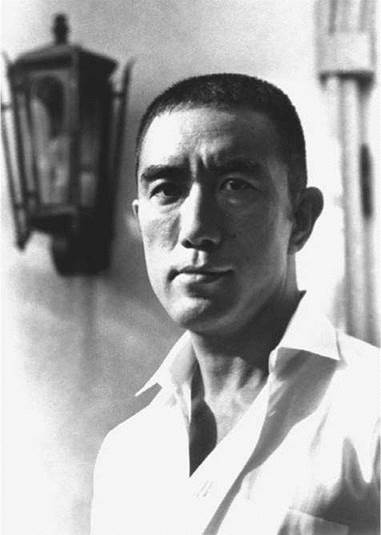

Yukio Mishima. Yukio Mishima, photograph. AP images.

Overview

Considered one of the most provocative and versatile modern Japanese writers, Yukio Mishima is known for the unorthodox views expressed in his fiction as well as for his eccentric personal life. His works often reflect a preoccupation with aggression and violent eroticism.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

A Dark Childhood. Mishima was born in Tokyo, where his father was a senior government official. His paternal grandmother, Natsu, was obsessively protective and would not allow Mishima to live on the upper level of their house with his parents; instead, she kept him confined to her darkened sickroom until he reached the age of twelve. Perhaps because of this extreme isolation, Mishima had difficulty developing social relationships as a youth.

In his autobiographical novel Confessions of a Mask, Mishima gives an uninhibited account of his struggles to come to terms with these inclinations and recalls that since childhood his ‘‘heart’s leaning was for Death and Night and Blood.’’ Several critics have referred to this statement as an apt summary of Mishima’s literary aesthetic, pointing to a tendency in both his personal life and his fiction to treat violence and death as sacred events. This passion and violence, which was characteristic of Mishima’s personal life, is also conveyed throughout his fiction.

Early Writing Career. Whatever the effect of his unconventional childhood, Mishima did well at the elite Peers School, belonging to a literary society there that was heavily influenced by the Japanese Romantic movement. After secondary school, Mishima passed easily into Tokyo University, where he studied law. Despite the fact that he was of age to be called for military service during the Pacific conflicts of World War II, Mishima escaped serving as a result of misdiagnosed tuberculosis. Ironically, for a man who was later to die wearing a uniform, Mishima admitted to having been relieved at his escape from the military. Mishima’s career as a writer officially began soon afterward.

Mishima began writing stories in middle school, and in 1941, when he was sixteen, his short fiction piece ‘‘Hanazakari no mori’’ was published in the small, nationalist literary magazine Bungei Bunka. ‘‘Hanazakari no mori’’ focuses on the aristocracy of historical Japan and displays the early development of Mishima’s acrid literary perspective. Many critics were impressed with the maturity of Mishima’s style and voice in this work, and Zenmei Hasuda, a member of the Bungei Bunka coterie, encouraged Mishima to approach the prominent intellectuals of a group of Japanese Romanticists known as the Nihon- Roman-ha. Many tenets of this group’s doctrine mirrored Mishima’s personal convictions, and he was particularly fascinated by their emphasis on death and violence. Stressing the ‘‘value of destruction’’ and calling for the removal of party politicians in an attempt to preserve the cultural traditions of Japan, the Nihon-Roman-ha had a profound influence on Mishima.

His first collection of stories, A Forest in Full Flower, appeared in 1944 when the literary establishment was more concerned with the war effort than with reviewing new works by unknown authors. Even so, Forest, a rather precious and self-consciously literary example of the Japanese Romantic school, sold out its first edition soon after publication. Mishima’s other stories and novellas from the early postwar period, The Middle Ages (1945), A Tale at the Cape (1947), and his first novel, Thieves (1948), also revel in a typically Romantic mixture of elements, among the most important being physically attractive young lovers; beautiful, youthful death; and the sea. These early elements remain constant throughout Mishima’s career, although in his later stages they were often reworked with various degrees of irony.

Philosophy and Politics. After receiving a law degree from Tokyo University in 1947, Mishima accepted a position with the Finance Ministry of Japan. He resigned within his first year, however, in order to devote himself entirely to writing. The extraordinary success of Confessions of a Mask solidified Mishima’s reputation as an important voice in Japanese fiction, and his subsequent endeavors in literature and drama were greeted with high critical acclaim. He received numerous literary awards and three nominations for the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Throughout his adult life, Mishima was disturbed by what he felt was Japan’s ‘‘effeminate’’ image as ‘‘a nation of flower arrangers.’’ He became increasingly consumed by a desire to revive the traditional values and morals of Japan’s imperialistic past and was vehemently opposed to the Westernization of his country. His ensuing works further reflect both his political orientation and his personal philosophy of ‘‘active nihilism,’’ which regards self-sacrifice as an essential gesture in achieving spiritual fulfillment. In affirmation of these personal convictions, Mishima, in 1970, committed seppuku, a traditional Japanese form of suicide by disembowelment.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Epic poems are long narrative poems in an elevated style that usually celebrate heroic achievement and treat themes of historical, national, religious, or legendary significance. They appear in every culture. Here are some other examples of epic poetry.

Nibelungenlied (c. 1200). This anonymous German epic recounts a story from the war between the east German Burgundians and the central Asian Huns in the fifth century.

Omeros (1990), by Derek Walcott. The Nobel Prizewinning poet retells the story of the Odyssey through West Indian eyes. The Caribbean island of St. Lucia reveals itself as a main character, and the poem itself is an epic of the dispossessed.

Paterson (1946-1958), by William Carlos Williams. This five-book serial poem was one of the first to redefine the epic, concerning itself with the city of Paterson, New Jersey, and examining modernization and its effects.

The Ring Cycle (1848-1874), by Richard Wagner. This cycle of four operas by the German composer is based on events from Norse sagas and the Nibelungenlied. The cycle is designed to be performed over the course of four nights, and the full performance takes about fifteen hours.

The Song of Roland (c. 1150). This anonymous French poem commemorates an eighth-century battle in the Pyrenees Mountains between Charlemagne's French army and the Muslim Saracens.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Mishima's famous contemporaries include:

Kobo Abe (1924-1993): A Japanese writer whose works have been compared to those of Franz Kafka.

Leon Uris (1924-2003): An American writer who produced numerous historical fiction and spy novels.

Flannery O'Connor (1925-1964): An American novelist and short-story writer often likened to William Faulkner.

Sam Peckinpah (1925-1984): An American film director well known for his innovative and explicit depictions of violence.

Richard Burton (1925-1984): A Welsh film actor nominated for seven Academy Awards.

Rod Serling (1924-1975): An American screenwriter best known for his work on the TV series The Twilight Zone.

Leo Esaki (1925-): A Japanese physicist who won the 1973 Nobel Prize in Physics and has contributed to technological development through his work for Sony and IBM.

Works in Literary Context

Mishima’s work consistently lamented the barrenness of postwar Japan and offered fictional visions to substitute for the culturally and economically depressed reality of the country in the 1950s and 1960s. The settings and images in Mishima’s writings were frequently taken from traditional Japanese culture but also occasionally from such Western writers as the Marquis de Sade.

Eroticism and Apocalyptic Visions. In Confessions of a Mask, Mishima first begins to explore the conflict between the disappointing real world and a fantasy world characterized by eroticism, violence, and beauty. This theme remained constant both in Mishima’s life and in his art. Mishima also displayed an interest in imminent apocalypse and violence. His 1962 novel Beautiful Star is a meditation in the form of a science fiction novel on the potential for worldwide destruction. Towing in the Afternoon (1963) continues the themes of violence and apocalypse, but on a more personal level, tells the story of a group of precocious sub-adolescent boys who murder a sailor in order to ‘‘give him a chance to be a hero again.’’ The novel also includes scenes of voyeurism and an implicit criticism of postwar Japanese materialism, themes that surface in later Mishima works.

Nihilism. During the last four years of his life, Mishima concentrated on his tetralogy, The Sea of Fertility, made up of four novels in which Mishima attempted to sum up both his entire philosophy of life and his view of the history of modern Japan. Each novel can be read on its own, but they are also woven together through an explicitly fantastic device: Mishima’s own interpretation of the theory of reincarnation. According to this theory, a young man named Kiyoaki who appears in the first novel (and dies at the end), is reincarnated in the next novel. In the final novel’s last page, the main character confronts the fact that all he has believed in, not only the reincarnation but the sense of intensity that believing in reincarnation has brought to him, has been fantasy. The novel’s last lines speak of an empty, sunny garden which, combined with the ironic title of The Sea of Fertility (which refers to an arid ‘‘sea’’ on the moon), suggests that Mis- hima’s final vision of Japan was of a barren wasteland where neither fantasy nor transcendence can exist.

In regards to his nihilism, Mishima is not alone among modern Japanese writers. Kawabata Yasunari, Abe Kobo, and Kenzaburo Oe, among others, have all shown the bleakness of the postwar period at the same time as they document characters seeking escape from this bleakness. But Mishima is perhaps the most thoroughgoing in his nihilism. Despite the fact that he himself organized a right-wing group and died shouting ‘‘Long Live the Emperor,’’ the final message of his fiction seems to suggest that even ideology offers no ultimate refuge.

Continued Influence. Mishima’s work is no longer as popular as it was during his life, but it also seems certain that it will no longer be dismissed for reasons of politics or even national embarrassment. He remains securely well known in the West, and even the younger generation of Japanese citizens is acquainted with several of his titles. An American director, Paul Schrader, has made a biographical film entitled Mishima (1985), and in 1993 the Swedish director Ingmar Bergman’s American production of Mishima’s play, Madame de Sade, drew rave reviews.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Throughout his writing career, Mishima demonstrated an interest in imminent apocalypse. Here are some other works that demonstrate a similar interest:

On the Beach (1957), a novel by Nevil Shute. This novel tells the story of survivors of a nuclear war who have a limited time to live because of the slow spread of radiation poisoning throughout the world.

The Stand (1978), a novel by Stephen King. In this epic tale of good versus evil, survivors of a plague travel across an America that has been decimated by disease and supernatural happenings.

La Jetee (1962), a film by Chris Marker. This short film tells the story of an experiment in time travel conducted after a nuclear war.

The Day After (1983), a made-for-TV movie directed by Nicholas Meyer. This movie depicts the impact of a major nuclearwar upon people living in the American Midwest.

Works in Critical Context

Often overshadowed by his dramatic personal life, Mishima’s fiction eludes easy critical analysis. His sensational death by seppuku has prompted many critics to elicit biographical meanings from his works, and critics often place him among the Japanese ‘‘I-novelists,’’ who wrote autobiography in the guise of fiction. Other commentators note a distinct contradiction between Mishima’s modern personal lifestyle and his literary aesthetic. Although critics have accused Mishima of self-indulgent prose, he is widely respected for his distinctive style, and most observers agree that he had made a significant contribution to world literature.

Death in Midsummer and Other Stories. Known to the West primarily for his novels, Mishima also composed more than twenty volumes of short stories. Only one of these, however—Death in Midsummer and Other Stories—has been translated into English. Like his novels, this collection has garnered praise from both Eastern and Western literary critics, and its stories display Mishima’s concern with a wide range of themes. The themes of the ten pieces in Death in Midsummer and Other Stories vary widely.

Perhaps the most critically discussed work in Death in Midsummer and Other Stories is ‘‘Patriotism.’’ Exemplifying Mishima’s tendency to present eroticism and death with shocking objectivity, this piece is considered crucial in understanding Mishima’s nihilistic creed. According to Lance Morrow, ‘‘Patriotism’’ reveals Mishima’s mastery of ‘‘what Russians call poshlust, a vulgarity so elevated—or debased—that it amounts to a form of art.’’ Based on the dual suicide of a young married couple during the 1936 Ni Ni Roku incident (in which a band of insurrectionists organized a rebellion against Japan’s military forces on behalf of the emperor), the story centers on the union of the couple’s physical and spiritual commitment to traditional ideals. Mishima himself described ‘‘Patriotism’’ as ‘‘neither a comedy nor a tragedy, but a tale of bliss.’’ The couple’s final sexual experience is treated as a prelude to their suicides, and the excruciating pain of the lieutenant’s suicide is linked with erotic desire: ‘‘Was it death he was now waiting for? Or a wild ecstasy of the senses? The two seemed to overlap, almost as if the object of this bodily desire were death itself.’’

Other works in the collection, including ‘‘The Priest of Shiga Temple and His Love,’’ ‘‘Onnagata,’’ and Mishima’s modern Noh play Dojoji, deal more specifically with the traditional character of Japan. Critics note Mishima’s delicate handling ofthe theme ofhomosexual love in ‘‘Onnagata,’’ which focuses on the lives of female impersonators in the traditional Kabuki theater. In ‘‘Onnagata,’’ as in his other stories, Mishima examines discomfiting emotional states with cool and uninhibited candor that is often startling to his readers.

Controversy. More than two decades after his death, Yukio Mishima is arguably still the most famous writer modern Japan has produced. The reasons for this fame are both complex and controversial. His critics may suggest that his notorious death by ritual suicide, which Mishima performed after having unsuccessfully called for the overthrow of the Japanese government, accounts as much for his renown as do his actual writings. His enthusiasts, whether in Japan or the West, do not dismiss the seppuku but dwell more on the brilliance of his style, the power of his imagination, and the fascination and variety of his themes—they include homosexuality, political terrorism, Zen, and reincarnation—all of which are in marked contrast to much of postwar Japanese fiction.

Whether his critics or his supporters are correct about the quality of either Mishima’s oeuvre or his political ideology, the fact remains that he is the most internationally renowned of Japan’s modern writers, a writer who has helped mold the Western imagination of Japan at the same time as one who continues to haunt the contemporary Japanese mind.

Responses to Literature

1. The subject matter of Mishima’s works can be shocking to many readers. What impact does this shock have on your reading ofthese works? In what ways does the shock enhance Mishima’s messages, and in what ways does it diminish from the power of his stories?

2. Many critics believe that Mishima’s books can be seen as autobiography in fictional form. What aspects of Mishima’s life are apparent in his novels? In what ways are his works not autobiographical?

3. Mishima ended his life with a ritual suicide. Write an essay that argues either that he deserves to be better remembered for this act than for his works, or that his works deserve to be appreciated for their brilliance and power apart from his suicide.

4. Mishima has been noted for the nihilism present in many of his novels. Identify several scenes from his novels that depict this nihilism most directly and write a critical analysis of these scenes, focusing on their effectiveness in conveying the author’s message and in convincing the reader to accept his philosophy of nihilism.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Azusa, Hiraoka. Segare Mishima Yukio. Tokyo: Bungei Shunjo, 1972.

Keene, Donald. Dawn to the West. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1985.

________. Landscapes and Portraits. Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1971.

Miyoshi, Masao. Accomplices of Silence. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974.

Nathan, John. Mishima: A Biography. Boston: Little, Brown, 1974.

Scott-Stokes, Henry. The Life and Death of Yukio Mishima. New York: Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, 1974.

Shoichi, Saeki. Hyoden Mishima Yukio. Tokyo: Shinchosha, 1978.

Takehiko, Noguchi. Mishima Yukio no sekai. Tokyo: Kodansha, 1968.

Takeshi, Muramatsu. Mishima Yukio. Tokyo: Bungei Shunjo, 1971.