World Literature

Ngugi wa Thiong’o

BORN: 1938, Kamiriithu, Kenya

NATIONALITY: Kenyan

GENRE: Fiction, nonfiction, drama

MAJOR WORKS:

A Grain of Wheat (1967)

Devil on the Cross (1980)

Wizard of the Crow (2004-2006)

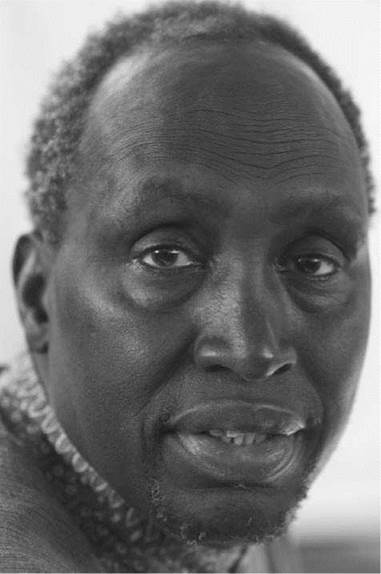

Ngugi wa Thiong’o. Geraint Lewis / Writer Pictures / drr.net

Overview

Kenyan author Ngugi wa Thiong’o is a pioneer in the literature of Africa. He published the first English language novel by an East African, Weep Not, Child (1964), and wrote the first modern novel in Gikuyu, a Kenyan language, Devil on the Cross (1980). Writing in Gikuyu enables him to communicate with the peasants and workers of Kenya.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

Political Unrest during Childhood. Born James Thiong’o Ngugi on January 5,1938, Ngugi wa Thiong’o was the son of Thiong’o wa Nduucu and Wanjika wa Ngugi. Ngugi was the fifth child of the third of Thiong’o’s four wives. Ngugi grew up in the city of Limuru in Kenya, a British colony at the time, as it had been since the late nineteenth century. Starting in 1952 with a rebellion against the British, a state of emergency was imposed throughout the country. English then became the language of instruction, and Ngugi learned English.

The state of emergency arose from the armed revolt of the Land and Freedom Army (called the ‘‘Mau Mau’’ by the British and made up of certain Kenyan tribes) against the injustices—particularly the unequal distribution of land—of the colonial system. The revolt was also caused by a growing sense of nationalism and a rejection of European dominance over Kenya. Ngugi’s elder brother joined the guerrillas between 1954 and 1956. As a consequence, Ngugi’s mother was detained for three months and tortured. On his return home after his first term at school, Ngugi found that, as part of the colonial forces’ anti-insurgency ‘‘protected’’ village strategy, his home had simply disappeared. The state of emergency lasted until 1959, and by its end, more than thirteen thousand civilians had been killed, nearly all African.

Ngugi attended Makerere University in Uganda and then the University of Leeds in England, where he was exposed to West Indian-born social theorist Franz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth, in which Fanon argues that political independence for oppressed peoples must be won—often violently—before genuine social and economic change is able to be achieved. But more influential were works by communism’s original theorists, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. By the early 1960s, he was writing for a living as a regular columnist for such Kenyan newspapers as the Sunday Post, the Daily Nation, and the Sunday Nation.

During this time, Kenya had achieved independence from Great Britain. After major Kenyan political parties agreed on a constitution in 1962, Kenya became independent on December 12, 1963. A year later, Kenya became a republic within the Commonwealth of Nations, a group of independent sovereign states many of which had been British colonies or dependencies.

Published Early Novels. During this time also, Ngugi began writing works that criticized Kenyan society and politics. Ngugi’s first novel, Weep Not, Child, is the most autobiographical of his fictional works and was written while a student at Makerere. Its four main characters embody the forces unleashed in central Kenya with the 1952 declaration of the state of emergency. The novel, written in English, was the first published English language novel by an East African writer.

In his second novel, The River Between (1965), Ngugi examined the relationship between education and political activism, and the relationship between private commitment and public responsibility. A Grain of Wheat (1967) followed. The four main characters of this novel reflect upon the Mau Mau rebellion and its consequences as they await ‘‘Uhuru Day,’’ or the day of Kenyan independence, achieved in 1963. Where A Grain of Wheat breaks most significantly with the earlier novels is in the abandonment of the idea of education as the key to solving Kenya’s problems and the acceptance, at least in the abstract, of the need for armed struggle. After writing A Grain of Wheat, Ngugi rejected the Christian name of James and began writing under the name Ngugi wa Thiong’o.

In 1968, Ngugi—then an instructor at the University of Nairobi—and several colleagues successfully campaigned to transform the university’s English Department into the Department of African Languages and Literature. Ngugi was named chairman of the new department. He became a vocal advocate of African literature written in African languages. Ngugi next accepted a year’s visiting professorship in African literature at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, before returning to University College in Nairobi, Kenya, in 1971. Before long, he was acting chairman and then chairman of the department.

Wrote Significant Plays. While Ngugi had written full-length plays as early as 1962—namely, The Black Hermit—he began focusing more attention on them in the mid-1970s. He began translating his play The Trial of Dedan Kimathi (1976) into Gikuyu in 1978, and, with fellow Kenyan playwright Ngugi wa Mirii, wrote another play in Gikuyu, Ngaahika Ndeenda (1977). It was translated into English as I Will Marry When I Want in 1982. Ngugi published his last English language novel, Petals of Blood, in 1977. That same year, in response to Ngaahika Ndeenda, the Kenyan government arrested and detained him for one year.

Wrote in Gikuyu While Detained. In detention, Ngugi wrote Detained: A Writer’s Prison Diary (1981). He also began writing his first Gikuyu language novel, Caitaani mutharaba-ini (1980) on sheets of toilet paper. Ngugi was never given any reason for his detention. Upon his release, he lost his position at the University of Nairobi. Although he continued to write nonfiction in English after this point, Ngugi wrote his novels and plays in Gikuyu and translated some of his works into other African languages.

Ngugi was occupied for the next two years with the English translation of Caitaani mutharaba-ini (Devil on the Cross, 1982) and his second collection of essays, Writers in Politics (1981). This collection is made up of thirteen essays, written between 1970 and 1980, the main concern of which is summed up by Ngugi in the preface: ‘‘What’s the relevance of literature to life?’’

Lived in Exile. In 1982, Ngugi left his country for a self-imposed exile. While Kenya had been very politically stable through the decades, the country’s National Assembly voted to formally make Kenya a one-party state in 1982. Later that same year, a group of junior air force officers, supported by university students and urban workers, tried and failed to impose a military coup. During his exile, Ngugi lectured at Auckland University in New Zealand, and those lectures were published as Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature (1986). This collection condenses many of his earlier arguments on language, literature, and society into four, often informatively autobiographical, essays.

In 1986, Ngugi announced that he would bid a complete ‘‘farewell to English.’’ Ngugi then published three children’s books in Gikuyu and a booklet, Writing Against Neocolonialism (1986), as well as a second novel in Gikuyu, Matigari ma Njiruungi (1986; translated as Matigari in 1989), which was banned in Kenya for a decade.

Since 1989, Ngugi has lived in the United States, teaching at universities in New York and California. In 2006, he published Wizard of the Crow, an English translation of his Gikuyu novel, Murogi wa Kagogo (2004), to glowing reviews. It is a political satire with elements of magical realism.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Thiong'o's famous contemporaries include:

Chinua Achebe (1930-): Nigerian novelist who chose to write in English in order to reclaim the language from its association with the British colonizers of Africa. His novels include Things Fall Apart (1958).

Wangari Muta Maathai (1940-): Kenyan environmental activist and member of Parliament who, in 2004, became the first African woman to receive the Nobel Peace Prize.

Gabriel Garcia Marquez (1927-): Colombian novelist and writer with radical political views and father of the ''magical realist'' movement in literature. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1982. His novels include One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967).

Daniel arap Moi (1924-): president of Kenya, 19782002, and ardent anti-Marxist, he established a singleparty state and presided over human rights abuses and a major corruption scandal.

Gao Xingjian (1940-): Chinese novelist, playwright, critic, and artist living in France, whose work is banned in China. In 2000, he became the first Chinese writer awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. His plays include Signal Alarm (1982).

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

While imprisoned, Ngugi wrote Detained, his memoir of the experience. Here are some other works written about or during the time their authors were in jail.

Consolation of Philosophy (c. 524), a philosophical treatise by Boethius. Jailed for treason and awaiting trial, the Roman Christian philosopher examines such issues as whether humans have free will and how evil can exist. This work uses classical philosophy to answer its questions and was very influential in the Middle Ages and Renaissance.

Long Walk to Freedom (1995), an autobiography by Nelson Mandela. Much of this book was secretly written during the twenty-seven years Mandela was imprisoned in South Africa for working against the apartheid regime, which segregated and oppressed nonwhite people. Mandela later became the first elected president of South Africa and received the Nobel Peace Prize.

Night (1958), a memoir by Elie Wiesel. This work by Wiesel, born a Romanian Orthodox Jew, describes his existence in the Auschwitz and Buchenwald concentration camps during World War II, during which his parents and sister died. It is considered a classic of Holocaust literature.

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (1962), novel by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. This short novel draws on the author's own experience of eight years in a Soviet labor camp. It was the first widely read work exposing repression in the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin.

This Earth of Mankind (1980), a novel by Pramoedya Ananta Toer. Imprisoned as a political prisoner by Indonesian president Suharto's regime and forbidden to write, Toer dictated this and three other novels to his fellow prisoners. The so-called Buru Quartet, named for the prison, examines the development of Indonesian nationalism.

Works in Literary Context

Ngugi has singled out three works as having impressed and influenced him in particular: Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart (1958), George Lamming’s In the Castle of My Skin (1953), and Peter Abrahams’s Tell Freedom (1954). Informally, Ngugi’s political thinking was revolutionized by his exposure to works by Karl Marx and Franz Fanon and by socialist academics. Apart from the West Indian writers on whom Ngugi’s university research focused, the specific literary influences to which he was first exposed at Leeds were German dramatist Bertolt Brecht’s plays and Irish-British novelist Robert Tressell’s The Ragged Trousered Philanthropists (1914), described by Ime Ikiddeh as a ‘‘major influence’’ on Ngugi.

History. Like their counterparts in other postcolonial settings, African writers confront a history that has been written about them by outsiders, a set of defining (often derogative) tropes and stories to which they often feel compelled to respond. They need to ‘‘remember’’ a history that his effectively been dismembered as a result of the violent encounter of colonialism. Thus revisiting Kenyan and Gikuyu history plays a central role in Ngugi’s works. His first novels are set in the recent colonial past; the middle novels, while set at the time of independence and after, feature extensive flashbacks as an integral part of their structure. Traditional Gikuyu stories, songs, myths, and customs, along with the stories and songs of the resistance movement before and after independence, are also key elements in this urge to recover an obscured or misrepresented past.

Such an oral tradition can be found in Devil on the Cross. In formal terms, the writing of this novel in Gikuyu has resulted in a far heavier reliance on devices drawn from, and deliberately signaling the novel’s relationship with, an oral tradition. The narrator refers to himself as ‘‘Prophet of Justice’’ and is addressed as ‘‘Gicaandi Player’’ on the opening page. Extensive use is made of proverbs and riddles in the dialogue; figurative language almost always has a local reference. Songs, particularly Mau Mau liberation songs, are integrated into the narrative.

Christian Imagery. Christian imagery and allusions feature prominently in all of Ngugi’s work. If this seems surprising from someone who does not call himself a Christian, it must be remembered that, as Ngugi regularly points out, Kenyans and especially the Gikuyu are widely Christianized, and the Bible is probably the one text with which a largely illiterate population is familiar. The Bible thus offers a rich and handy store of characters, events, and symbols for a writer to exploit. Ngugi’s cast of characters contains a wealth of Moses, Messiah, and Judas figures alongside allusions and quotations from the book of Psalms, the prophets, and Gospel parables.

Works in Critical Context

Critics have consistently acknowledged Ngugi as an important voice in African letters. He has been called the voice of the Kenyan people by certain commentators, while others have lauded his novels as among the most underrated and highest quality to come from Africa. Ngugi’s fiction has been noted for its overtly political agenda, its attempt to give a literary voice to the poor of Kenya, and its consistent critique of colonization and oppressive regimes. Critics have also praised Ngugi’s role as an influential postcolonial African writer, particularly in his portrayal of corrupt postliberation African governments.

A Grain of Wheat. A Grain of Wheat is widely considered by critics to be Ngugi’s most successful novel, as he had honed the skills that were less evenly displayed in his first two books. Angus Calder wrote that A Grain of Wheat ‘‘is arguably the best, and certainly the most underrated novel to come from Black Africa.’’ Taking A Grain of Wheat and Petals of Blood together, Gerald Moore asserts that these two novels ‘‘form the most impressive and original achievement yet, in African fiction.’’

Wizard of the Crow. This novel has received near universal praise from critics. Stuart Kelley wrote that he had ‘‘every expectation that [Ngugi’s] new novel, Wizard of the Crow, will be seen in years to come as the equal of [Salman Rushdie’s] Midnight’s Children, [Gunter Grass’s] The Tin Drum, or [Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s] One Hundred Years of Solitude; a magisterial magic realist account of 20th-century African history. It is unreservedly a masterpiece.’’

Other critics praised Ngugi’s ability to express the colonial and postcolonial attitudes of Africans as well as his storytelling ability. David Hellman believed that ‘‘the effort to throw off the shadow chains of the [colonial] past while establishing an authentically African continuum has been at the thematic center of much African literature, but in Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s epic novel, Wizard of the Crow, this theme may well have found its ultimate expression.’’ And Scottish-African writer and critic Aminatta Forna noted that ‘‘ Wizard of the Crow is first and foremost a great, spellbinding tale, probably the crowning glory of Ngugi’s life’s work.... He has turned the power of storytelling into a weapon against totalitarianism.’ ’

Responses to Literature

1. What should the relationship be between education and political activism? Do people have a responsibility to speak up against oppression and for their beliefs? What if speaking out will put them or their families in danger? What would you do? Write an essay that outlines your responses to these complex questions.

2. Ngugi has asked, ‘‘What is the relevance of literature to life?’’ Write an essay responding to his question. Use specific examples in your response.

3. Write your own definition of political action. Did you include writing a novel as being a political act? Why or why not?

4. Research novelist Chinua Achebe’s reasons for choosing to write in English. Write an essay analyzing his reasons for doing so, and contrast them with Ngugi’s reasons for refusing to write in English. Whose point of view do you agree with more? Why?

5. Research Martinique revolutionary Franz Fanon’s political views in terms of liberation and anticolonial movements. Write an essay summarizing his position, then explain your own opinion.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Cook, David, and Michael Okenimkpe. Ngugi wa Thiong’o: An Exploration of His Writings. London: Heinemann, 1983.

Gurr, Andrew. Writers in Exile: The Identity of Home in Modern Literature. Brighton, U.K.: Harvester, 1981.

Moore, Gerald. ‘‘Towards Uhuru.’’ In Twelve African Writers. London: Hutchinson, 1980.

Palmer, Eustace. The Growth of the African Novel. London: Heinemann, 1979.

Parker, Michael, and Roger Starkey, eds. Postcolonial Literatures: Achebe, Ngugi, Desai, Walcott. New York: St. Martin’s, 1995.

Robson, Clifford B. Ngugi wa Thiong’o. London: Macmillan, 1979.

Periodicals

Martini, Jurgen, et al. ‘‘Ngugi wa Thiong’o: Interview.’’ Kunapipi 3, nos. 1 & 2 (1981): 110-16; 135-40.

Mbughuni, L. A. ‘‘Old and New Drama from East Africa.’’ African Literature Today 8 (1976): 85-98.

Reed, John. ‘‘James Ngugi and the African Novel.’’ Journal of Commonwealth Literature 1 (September 1965): 117-21.

Sicherman, Carol M. ‘‘Ngugi wa Thiong’o and the Writing of Kenyan History.’’ Research in African Literatures 20 (1989): 347-70.

Web Sites

Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s home page. Ngugi wa Thiong’o.org. Retrieved March 20, 2008, from http://005a660.netsolhost.com/index.html