World Literature

Ben Okri

BORN: 1959, Minna, Nigeria

NATIONALITY: Nigerian

GENRE: Fiction, poetry

MAJOR WORKS:

Flowers and Shadows (1980)

The Landscapes Within (1981)

The Famished Road (1991)

Songs of Enchantment (1993)

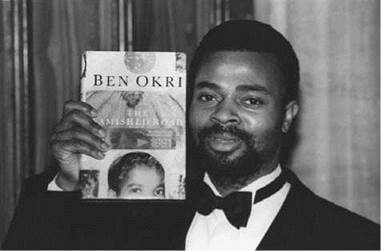

Ben Okri. Okri, Ben, London, 1991, photograph. AP Images.

Overview

Nigerian novelist, poet, and short-story writer Ben Okri continually seeks to capture the post-independence Nigerian worldview, including the civil war and the ensuing violence and transformation, no matter how troubling or painful these events may be. He is known as an ambitious, experimental writer who seeks to abandon conventional European notions of plot and character. Among his best-known works is the novel The Famished Road (1991), which won the 1991 Booker Prize for Fiction.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

Return to Africa. Okri was born in Minna, Nigeria, on March 15, 1959, to Silver Oghenegueke Loloje Okri, an Urhobo from near the town of Warri, on the Niger Delta, and Grace Okri, an Igbo from midwestern Nigeria. In 1961, Okri’s father left for England to pursue a law degree at the Inner Temple in London. After the family had joined him some months later, the Okris settled in Peckham, in the Greater London borough of Southwark. From September 1964, Okri attended John Donne Primary School, a rough primary school in Southwark. After his father had been called to the bar in July 1965, Okri was horrified to discover that he and his mother had to return to Nigeria. He went back to Nigeria, both a stranger and an innocent, at the age of six.

The Nigeria he had been born in was as unstable as the one he returned to in the mid-1960s. In October 1960, Nigeria gained its full independence from Great Britain and became a fully independent member of the British Commonwealth. The new republic almost immediately was embroiled in internal unrest, primarily caused by the complex ethnic compositions of its regions. In early 1966, these tensions resulted in a military coup that put Major General Johnson Aguiyi-Ironsi in power. A countercoup a few months later led to the murder of the general, and he was replaced by Lieutenant Colonel Yakubu Gowon as head of the military government. Civil war soon began between the military government and the republic, which ended in 1970 with Gowon and his military regime in control until the mid-1970s. After Gowon failed to transfer power to civilian rule as promised, he was overthrown in 1975. Political unrest continued, however.

Immigrated to England. In this atmosphere, Okri started his first novel in 1976, at age seventeen. Armed with the manuscript of his novel, Okri left Nigeria for England in 1978 after he was denied entrance to Nigerian universities. Okri lived with his uncle in New Cross, in the inner-London borough of Lewisham, while working as staff writer and librarian for Afroscope, a France-based current-affairs digest, and attending evening classes in Afro-Caribbean literature at Goldsmiths College in New Cross. Awarded a Nigerian government scholarship, Okri enrolled in 1980 as an undergraduate at the University of Essex, where he later obtained a BA in comparative literature.

Published First Novels. Okri’s first novel, Flowers and Shadows, was published in 1980, when he was twenty-one. His second novel, The Landscapes Within (1981), came out the following year. They were generally ignored by critics and the book-buying public, forcing the author to live on the streets and subway stations for a time. From 1983 to 1987 Okri served as poetry editor for the London-based weekly magazine West Africa. Although he enjoyed the job, he was depressed by the poems submitted to the journal, which were almost exclusively about human suffering. In the end, he was fired because he was not publishing enough poetry. At the same time, Okri started to work as a freelance broadcaster for the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) African Service, introducing the current affairs and features program Network Africa. One year later, he was awarded a bursary by the Arts Council of Great Britain that allowed him to continue work on his writing.

Artistic Success. In 1991, Jonathan Cape published Okri’s The Famished Road, the first in a trilogy of novels centered on the same characters. That same year, Trinity College of Cambridge University named Okri the Trinity Fellow Commoner in the Creative Arts, an award that gave him the salary of an academic and allowed him to continue his writing. The Trinity judges were much influenced by the qualities of Stars of the New Curfew (1986) and had the opportunity of reading The Famished Road in proof form.

Okri published the second volume in The Famished Road trilogy, titled Songs of Enchantment, in 1993. The third volume, Infinite Riches, appeared five years later. In 1997, Okri was elected vice president of the English branch of International PEN and was made a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature. He was named a member of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in 2001.

While winning awards, Okri continued to write challenging novels. They include Astonishing the Gods (1995), which was concerned with the same thematic material as the Famished Roads novels. In 2002, he published Arcadia, which diverged sharply from his previous works by focusing on Lao, an ordinary television reporter. Okri published the novel Starbook in 2007, and continues to live and work in London.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Okri's famous contemporaries include:

Mark Z. Danielewski (1966-): American experimental writer whose novels include House of Leaves (2000) and Only Revolutions (2006).

Cyprian Ekwensi (1921-2007): Nigerian author credited with popularizing the novel in Nigeria. His novels include Jagua Nana (1961).

Dick Francis (1920-): English author who has published prolifically since the early 1960s. His first book was his autobiography of his horse jockey days, The Sport of Queens (1957).

David Lynch (1946-): American filmmaker whose Eraserhead (1977) made him a cult hero. His later films include The Elephant Man (1980) and Blue Velvet (1986).

Benazir Bhutto (1953-2007): Pakistani politician who was the first woman to serve as prime minister of Pakistan.

Tony Blair (1953-): British politician who served as prime minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 until 2007.

Works in Literary Context

It is not surprising that critic Giles Foden sees influences as disparate as African mythology and Western science fiction in the work of Okri, given the depth and breadth of Okri’s reading. He began reading the classics of the Western tradition—Charles Dickens and William Shakespeare, for example—in his early teen years. As he grew and became more concerned with Nigerian politics and society, his reading also grew. Indeed, his early work can be fruitfully compared with the novels of Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka—both African novelists—and James Joyce, the acclaimed Irish author, and his later work shows the marks of the African ‘‘animist’’ tradition—akin to ‘‘magical realism’’—in which spirits and spiritual phenomena take physical form.

The Artist in Nigeria: The kunstlerroman. Okri’s works frequently focus on the political, social, and economic conditions of contemporary Nigeria. In Flowers and Shadows, for example, Okri employs paradox and dualism to contrast the rich and poor areas of a typical Nigerian city. Set in the capital city of Lagos, the novel focuses on Jeffia, the spoiled child of a rich man, who realizes his family’s wealth is the result of his father’s corrupt business dealings. In The Landscapes Within, the central character, Omovo, is an artist who, to the consternation and displeasure of family, friends, and government officials, paints the corruption he sees in his daily life.

Detailing the growth and development of the protagonist as well as that of Nigeria, The Landscapes Within has been classified as a kunstlerroman—a novel that traces the evolution of an artist—and favorably compared with other works in the genre, notably James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916) and Ayi Kwei Armah’s The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born (1968). The clarity and precision of Okri’s style owe something to Chinua Achebe in The Landscapes Within, and his vision of social squalor and human degradation is as unflinching and as compassionate as that of Wole Soyinka. Omovo is actually described at one point reading Soyinka’s novel The Interpreters (1965), whose title points up the social significance of his own artistic dedication.

Animism. The Famished Road tells the story of an abiku, a child who is born to die and return again and again in an endless cycle to plague his mother. Okri makes of this myth a parable of migrancy, transition, and metamorphosis. Having made a pact with his spirit-companions to return soon, Azaro refuses to return after birth and struggles to hold on to life despite the temptations of his companions in the spirit world.

Reviewers and critics often point to Okri’s debt to magical realism and writers such as Gabriel Garcia Marquez. One of the essential features of African animist thought is a dogged refusal to conceive of abstractions that cannot be physically represented. Ancestors, spirits, gods, and other mythical figures necessarily possess palpable physical characteristics. The animist imagination imposes no inherent radical dichotomies on the world, as Western thought has done. The animist understands not the principles of singular identity and contradictions but those of plurality and metamorphosis. The abiku is both human and nonhuman and moves between those states as easily as water turns to ice or steam.

The ‘‘animist realism’’ of The Famished Road makes it possible to evoke naturally, within a single narrative, simultaneous orders of existence. The motifs of the spirit boxer, the local lore surrounding the photographer, the various figures from folk beliefs who take over people’s bodies or see with their eyes, and the domineering presence of the road, all give this novel a distinctively Nigerian flavor that links it with the works of D. O. Fagunwa, Amos Tutuola, Wole Soyinka and J. P. Clark. The major achievements of the author are his ability to carry his audience along and his acceptance of the major parameters of the world he creates, a world that ‘‘straddles twilights.’’

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Many fiction writers, like Okri, often take current events, couch them in their novels and short stories, and in so doing allow the ridiculousness or grotesque nature of these incidents to shine. Here are a few more works of art that utilize real-life events in order to critique them:

The Jungle (1906), a novel by Upton Sinclair. This social commentary on the plight of the working class uses as its basis the meatpacking industry, describing the horrifying working conditions that meatpackers must endure in the process.

Elmer Gantry (1926), a novel by Sinclair Lewis. This work exposes the godlessness and hypocrisy of a fictional preacher—a composite of a number of preachers Lewis met while researching the novel.

Heart of Darkness (1902), a novella by Joseph Conrad. Inspired by Conrad's own experiences working on the Congo River as a steamboat captain, this work describes the horrendous exploitation of native inhabitants along the Congo by a Belgian trading company.

Works in Critical Context

Stressing his inclusion of African myth and folklore, emphasis on spirituality and mysticism, and focus on Nigerian society and the attendant problems associated with the country’s attempts to rise above its third world status, critics have lauded Okri’s writings for capturing the Nigerian worldview. Okri has additionally received praise for his use of surrealistic detail, elements of Nigerian storytelling traditions, and Western literary techniques, notably the magic realism popularized by Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Placing Okri’s works firmly within the tradition of postcolonial writing and favorably comparing them with those of such esteemed Nigerian authors as Chinua Achebe, critics cite the universal relevance of Okri’s writings on political and aesthetic levels.

The Famished Road. Okri’s novel The Famished Road explores the Nigerian dilemma. Charles R. Larson, writing in the World & I, remarked that ‘‘the power of Ben Okri’s magnificent novel is that it encapsulates a critical stage in the history of a nation ... by chronicling one character’s quest for freedom and individuation.’’ The Famished Road's main character is Azaro, an abiku child torn between the spirit and natural world. His struggle to free himself from the spirit realm is paralleled by his father's immersion into politics to fight the oppression of the poor. The novel introduces a host of people, all of whom ‘‘blend together ...to show us a world which may look to the naked eye like an unattractive ghetto, but which is as spiritually gleaming and beautiful as all the palaces in Heaven—thanks to the everyday, continuing miracle of human love,’’ wrote Carolyn See in the Los Angeles Times.

By novel's end, Azaro recognizes the similarities between the nation and the abiku. Each is forced to make sacrifices to reach maturity and a new state of being. This affirming ending also ‘‘allows rare access to the profuse magic that survives best in the dim forests of their spirit,'' according to Rob Nixon of the Village Voice. Similarly, in her appraisal for the London Observer, Linda Grant commented, “Okri’s gift is to present a world view from inside a belief system.’’ Detroit Free Press contributor John Gallagher deemed the work ‘‘a majestically difficult novel that may join the ranks of greatness.’’

Songs of Enchantment. In Songs of Enchantment, Okri continues to explore the story and themes raised in The Famished Road. While the focus in the first book was on the efforts of Azaro's parents to keep him among the living, however, the focus in the second book is, wrote Charles R. Larson in the Chicago Tribune, ‘‘an equally difficult battle to restore the greater community to its earlier harmony and cohesiveness.'' Songs ofEnchantment more clearly explicates Okri's concerns with the problems visited upon Africa after decolonization. Wrote Larson, ‘‘The wonder of Songs of Enchantment... is that it carries on so richly the saga of nation building implying that countries that have broken the colonial yoke may face an even more difficult struggle.’’

Responses to Literature

1. Read The Landscapes Within and James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, both of which are about the growth of young novelists into men. In a paper, compare Okri’s description of the growth of the artist in his novel with Joyce's description of the same. How do issues like geographic location and historical context affect their representation of artists’ coming of age? In your response, cite relevant passages from the novels to support your position.

2. Read The Famished Road. This novel includes elements of animism—in which spirits and spiritual phenomena are represented in physical objects. What effect does Okri achieve by including these elements of animism? In other words, how do you think the novel would be changed if it did not include animism? Write a paper that outlines your response.

3. Okri uses current events to illustrate certain points he wishes to make in his fiction. These current events are often chosen because they epitomize some viewpoint or the ridiculousness of a certain action. (Think of the politician harming his potential voters by dropping heavy but worthless coins on their heads from a helicopter.) Pick a current event that you think illustrates the foibles of a particular worldview or the ridiculousness of some set of beliefs or practices. Then, try to spin a short story out of this single current event. Visit the short fiction of Okri, especially Stars of the New Curfew, to get an idea of how to do this effectively.

4. Using the Internet and the library, research abiku. In what ways does Okri deviate from traditional representations of the abiku in The Famished Road? What effect does Okri achieve by deviating from these representations? Construct your response in the form of an essay.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Costantini, Mariaconcetta. Behind the Mask: A Study of Ben Okri’s Fiction. Rome: Carocci, 2002.

Fraser, Robert. Ben Okri: Towards the Invisible City. Tavistock, U.K.: Northcote House, 2002.

Killam, Douglas, and Ruth Rowe, eds. The Companion to African Literatures. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000.

Parekh, Pushpa Naidu, and Siga Fatima Jagne, eds. Postcolonial African Writers: A Bio-Bibliographical Critical Sourcebook. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood, 1998.

Quayson, Ato. Strategic Transformations in Nigerian Writing: Orality and History in the Work of Rev. Samuel Johnson, Amos Tutuola, Wole Soyinka & Ben Okri. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1997.

Periodicals

Boylan, Clare. ‘‘An Ear for the Inner Conversation.’’ Guardian (London), October 9, 1991.

Falconer, Delia. ‘‘Whisperings of the Gods: An Interview with Ben Okri.’’ Island (Winter 1997).

Grant, Linda. ‘‘The Lonely Road from Twilight to Hard Sun.’’ Observer (London) October 27, 1991.

Shakespeare, Nicholas. ‘‘Fantasies Born in the Ghetto.’’ Times (London), July 24, 1986.