World Literature

Pier Paolo Pasolini

BORN: 1922, Bologna, Italy

DIED: 1975, Ostia, Italy

NATIONALITY: Italian

GENRE: Fiction, nonfiction, drama

MAJOR WORKS:

Poesie a Casarsa (1942)

The Ragazzi (1955)

A Violent Life (1958)

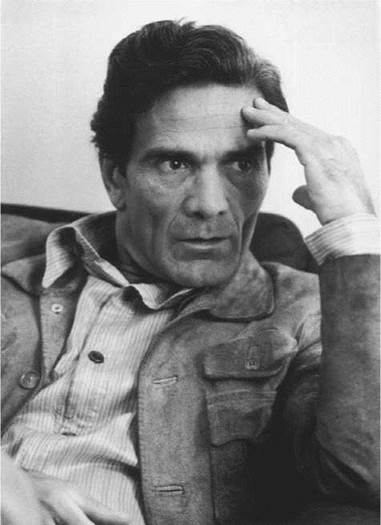

Pier Pasolini. Evening Standard / Hulton Archive / Getty Images

Overview

Pier Paolo Pasolini is best known throughout the world primarily for his films, many of which are based on literary works, such as The Decameron and The Canterbury Tales. In his native Italy, however, Pasolini is recognized as a complex artist: a celebrated novelist, poet, and critic as well as a filmmaker. As one of the most influential and controversial writers of his generation, Pasolini produced both literary and cinematic art that reflects his empathy for the poor, his religious conviction, and his involvement in nonconformist politics.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

A Child of Casarsa. Pasolini was born March 5, 1922, in Bologna, Italy. His childhood and early adult experiences in the poverty-stricken village of Casarsa, located in the province of Friuli, forever linked him to the poor, inspiring sympathies that would later emerge in his writing. In addition to the plight of the people there, Pasolini was influenced by the dialect spoken in that region, as evidenced by his early poetry.

In 1937, Pasolini attended the University of Bologna, where he studied art history and literature and began publishing articles in Architrave, a student politico-literary journal. At his own expense, he published his first collection of poetry, Poesie a Casarsa, in 1942. These poems reveal a deep love for the Friulian language, landscape, and peasants that had so shaped his childhood.

Political Affiliations. Pasolini grew up at a time when Fascism was the rule of law in Italy. Fascism is characterized by intense nationalism over other interests—including individual rights—as well as a strong military state and an authoritarian leader, who controls the government with little opposition by a legislature or parliament. In Italy, this leader was Benito Mussolini, who ultimately joined Hitler and his Nazi forces as part of the Axis Powers during World War II. Pasolini was drafted as a reluctant soldier during this time.

Relieved of his duties after only a week of military service in 1943, Pasolini fell under the influence of the ideas of Karl Marx and Antonio Gramsci, the leading voice of Italian communism at the time. Communism emphasizes the importance of workers’s rights and the sharing of wealth and resources among productive members of society. From 1943 to 1949, while teaching at a public school, Pasolini dedicated himselfto intellectual and artistic pursuits, writing and publishing poetry in the Friulian dialect with the hope of creating a literature accessible to the poor. Pasolini’s writing became his form of protest and resistance against Nazism and Fascism, as well as a rejection of the official language of Italy, which he believed had been created by and for the bourgeoisie. In 1949, after being arrested for his involvement in a homosexual relationship, Pasolini lost his teaching position and was expelled from the Italian Communist Party. Seeking to escape the scandal, Pasolini and his mother moved to Rome, where he became immersed in the city’s slum life, all the while documenting the depravity of that lifestyle in poetry and such novels as A Violent Life.

In 1957’s The Ashes of Gramsci, Pasolini returned to ideological debate. After being inspired by a visit to the grave of Gramsci, Pasolini wrote a meditation of passion and ideology that neither embraces nor challenges Marxism: While he accepted the rational arguments of Gramsci, Pasolini was tormented by his simultaneous attraction to and revulsion for the world around him. Instead of coming to a resolution, Pasolini establishes a tension between the movements of history and individual desire.

Filmmaker. In addition to writing—especially scriptwriting—Pasolini worked as an actor in the 1950s and, in 1961, made his debut as a director with the film Accatonne, an adaption of his novel A Violent Life. For the next fourteen years, he made films in which he combined his socialist sensibilities with a profound, nondenominational spirituality. Most always controversial, his movies were often anti-Catholic and sexually explicit, and he was officially accused of blasphemy by the Catholic Church in 1962. As a director, he was known for constantly changing his style and artistic approach, using nonprofessional actors, avoiding many industry standards, and choosing his subject matter from classical legends, tragedies, political diatribes, and other unconventional sources.

Mysterious Murder Murdered by a young male prostitute, Pasolini was found on the morning of November 2, 1975, in the seaside resort of Ostia. Accounts of his death differ: Some sources say Pasolini was hit in the head with a board and then run over repeatedly with his own car; others say he was bludgeoned to death. Some people even believe that the killer was an assassin sent by one of Pasolini’s political enemies.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Pasolini's famous contemporaries include:

Akio Morita (1921-1999): Morita founded Sony, the Japanese electronics company that built the first transistor radio, the Walkman portable cassette player, and the 3.5-inch floppy disk.

Arthur C. Clarke (1917-2008): In 1945, this English science-fiction author, most famous for his novel 2001: A Space Odyssey, predicted worldwide communication using satellites.

Robert Redford (1931-): An Oscar-winning director as well as a legendary actor, Redford founded the Sundance Film Festival and Sundance Institute, an organization dedicated to the discovery and development of independent filmmakers.

Allen Ginsberg (1926-1997): Ginsberg, author of the notorious Howl, and Other Poems was an American Beat poet, a group of writers who detested middle-class values.

Terence Rattigan (1911-1977): The successful comedies by this English playwright are based on actual people and incidents.

Nadine Gordimer (1923-): Much of Gordimer's work deals with the moral and psychological tensions in a racially divided South Africa, her native country.

John Bowen (1924-): The work of this British novelist and playwright is noted for its complex and ambivalent human motives and behavior.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

One theme that recurs in Pier Paolo Pasolini's work is the belief that innocence is being corrupted by capitalism. Especially in the years after World War II, intellectuals have explored this idea in both fiction and nonfiction works. Listed below are examples of books that address materialism and innocence in capitalist societies:

The Pearl (1945), a novella by John Steinbeck. As Kino, the main character in this novel, seeks wealth and status via the pearl, he becomes a savage criminal, personifying the way ambition and greed destroy innocence in a materialistic, capitalistic society.

Fighting Evil: Unsung Heroes in the Novels of Graham Greene (1997), nonfiction by Haim Gordon. This book offers a discussion of the evils of capitalism in the works of Graham Greene and the thought of Thomas Hobbes.

The Innocent (1990), a novel by Ian McEwan. Concerned with the postwar struggle between the political philosophies of communism and capitalism, this novel is also about deception, aggression, and the loss of innocence.

Kekexili: Mountain Patrol (2004), a film by Chuan Lu. This film, based on a true story about Tibetan volunteers attempting to stop poachers from hunting endangered antelope, depicts the lure of capitalist influence in remote areas and shows how ideals can be affected by desperate circumstances.

Works in Literary Context

Without a doubt, Pasolini’s work was most inspired by the time he spent among the poverty stricken in Casarsa and in the slums of Rome. Stylistically, his poetry shows inspiration from several poets, including Giovanni Pascoli, the subject of Pasolini’s thesis, and Eugenio Montale. Many of the poems in Poesie a Casarsa, Pasolini’s earliest volume, are written in the terza rima form—a three-line stanza with the rhyme scheme aba, bcb, cdc, etc.—invented by Dante in his Divine Comedy.

The Language of Art and Politics. Suggests writer Tony D’Arpino, ‘‘Pier Paolo Pasolini, poet, novelist, philosopher, and filmmaker, came of age during the reign of Italian fascism, and his art is inextricably bound to his politics.’’ This opinion unites much of Pasolin’s work, as he often employs his social and cultural ideologies as poetic inspiration and the basis for a new mythology. He resisted the ‘‘unreal, functional, unpoetic languages of the bourgeoisie,’’ as Sam Rohdie notes, ‘‘the languages of reason, of modern society, of capitalism, of exploitation, of politics.’’ Instead, Rohdie says, Pasolini attempted to capture the language of ‘‘the earthly real.’’ Pasolini challenged what he called ‘‘practical politics’’ with collages composed of what he viewed as true world realities: ‘‘language, gestures, faces, bodies.’’ In a sense, Pasolini looked toward a ‘‘primitive world,’’ at the same time addressing the artifice of the ‘‘bourgeois world.’’

Slang in The Ragazzi. Based on Pasolini’s experiences in the Roman slums, the highly controversial novel The Ragazzi tells the story of a group of young people whose poverty has driven them to a life of violence, crime, and indiscriminate sex. Pasolini, rejecting the formal official language of Italy, uses crude, obscene Roman street slang to create a shocking picture of Italian youth. In fact, although it avoids overt political implications, The Ragazzi is regarded as an indirect comment on the Italian establishment as a whole. Because of his harsh, explicit language, Pasolini angered many groups and was charged with obscenity, of which he was acquitted.

Works in Critical Context

Critical reaction to Pasolini’s work usually extends beyond its value as literature or film because of its inclination toward political and religious thought. Over the course of his career, his explorations of communism, Catholicism, and class struggles alternately pleased and angered conservatives and liberals alike. According to an essay by Joseph P. Consoli in Gay and Lesbian Literature, actor Stefano Casi said that ‘‘Pasolini was first a thinker, and then an artist,’’ that despite the many genres in which Pasolini worked, ‘‘in reality only one definition can render with precision the area of cultural diligence attended to by Pasolini: intellectual.’’ As a result, scholars look beyond the story itself for meanings and messages, often citing them as evidence for his position for or against a particular theory, practice, or political system.

Poetry. Most critics agree that Pasolini’s greatest contribution to literature is the creation of a ‘‘civic’’ poetry, verse that conveys the rational argument of a civilized mind. Intellectuals have considered Pasolini an ‘‘organic intellectual,’’ a term first used by Gramsci to designate a militant intellectual who personally identified with the working class. Still, Pasolini’s poetry is viewed by some as eluding historically established classification. While the intimate candor of Pasolini’s poetry has been praised by some critics, others have found fault in his failure to resolve his internal struggles in his work, along with his inclination toward egocentrism and martyrdom.

Adapting Oedipus Rex. In Pasolini’s version, Oedipus Rex (1967) takes on the image of the Everyman and appeals to the ordinary person. Pasolini uses only the basic elements of the mythical hero and hones in on Oedipus’s sense of alienation and fear. Pasolini’s Oedipus lives in the 1930s, with a lower middle class Italian family. He unifies, as Kostas Myrsiades offered, ‘‘the ancient myth and Pasolini’s own childhood,’’ plus ‘‘the psychological relationship between Oedipus and all men who as children have rivaled their fathers for their mother’s affections.’’ Audrene Eloit in Language Film Quarterly went further, calling the work a ‘‘palimpsest,’’ which points to the layers of mythical retellings and adaptations of the Oedipus story originally written by Sophocles. Eloit also claims the film ‘‘turns into a map of the soul, a translation of the works of Freud and his successors,’’ and thematically focuses on the debate between free will and fate in the context of psychoanalysis. Vincent Canby of the New York Times suggests the film ‘‘contains somewhat more Pasolini than Sophocles’’ and praises the ‘‘modern, semi-autobiographical sequences’’ where the myth and author intersect. Most critics found the movie visually stunning and honored it with several awards, including the Best Foreign Language Film at the Kinema Jumpo Awards.

Responses to Literature

1. Some scholars believe that Pasolini's poetry was influenced by both Dante and American poets. Read a selection of Pasolini's poetry. Write an essay describing what evidence you find of such influences.

2. Pasolini achieved fame in Italy with novels based on his experiences in the Roman slums and his impressions of urban poverty. Compile a list of five or more authors today who write about life in undesirable conditions. What genres do these works encompass? Do you think fiction or nonfiction is a more effective vehicle for describing such conditions?

3. Biographers often write about the innocence with which Pasolini viewed the world. However, his works, filled with obscenities and acts of violence, do not convey such an outlook. With a group of your classmates, discuss how you can reconcile Pasolini's worldview with his works. Why do you think an optimist in his real life would create such controversial films and literature?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Malinowski, Sharon, ed. Gay and Lesbian Literature. Detroit: St. James, 1994.

Peterson, Thomas E. The Paraphrase of an Imaginary Dialogue: The Poetics and Poetry of Pier Paolo Pasolini. New York: Peter Lang, 1995.

Rhodie, Sam. The Passion of Pier Paolo Pasolini. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995.

Schwartz, Barth David. Pasolini Requiem. New York: Pantheon, 1992.

Ward, David. A Poetics of Resistance: Narrative and the Writings of Pier Paolo Pasolini. Madison, N.J.: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1995.

Periodicals

Allen, Beverly. ‘‘The Shadow of His Style.’’ Stanford Italian Review II2 (Fall 1982): 1-6.

Capozzi, Frank. ‘‘Pier Paolo Pasolini: An Introduction to the Translations.’’ Canadian Journal of Italian Studies 1-2 (Fall-Winter 1981-1982): 109-13.