World Literature

Boris Pasternak

BORN: 1890, Moscow, Russia

DIED: 1960, Peredelkino, USSR.

NATIONALITY: Russian

GENRE: Fiction, Poetry

MAJOR WORKS:

Sister My Life: Summer, 1917 (1923)

The Last Summer (1934)

Doctor Zhivago (1956)

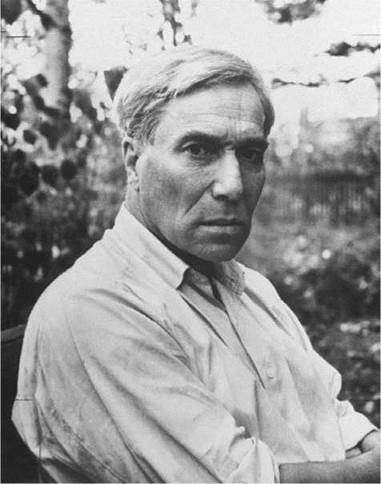

Boris Pasternak. Jerry Cooke / Time Life Pictures / Getty Images

Overview

Nobel laureate Boris Pasternak was regarded in his native Russia as one of the country's greatest postrevolutionary poets. He did not gain worldwide acclaim, however, until his only novel, Doctor Zhivago, was published in Europe in 1958, two years before the author’s death. Banned in Russia as anti-Soviet, the controversial novel was hailed as a literary masterpiece by both American and European critics, but its publication was suppressed in Russia until 1988.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

A Childhood of High Culture. The son of an acclaimed artist and a concert pianist, both of Jewish descent, Pasternak benefited from a highly creative household that counted novelist Leo Tolstoy, composer Alexander Scriabin, and poet Rainer Maria Rilke among its visitors. In 1895, when Pasternak and his brother, Aleksandr, became gravely ill for a brief time, Pasternak’s mother stopped playing music in public for ten years. Apparently, her decision to end her public concerts was a source of guilt for the children. Pasternak’s image of his mother’s sacrifice manifests itself throughout his work in the persistent theme of women and their difficult lot in life.

Association with the Futurists. After spending six years studying music, Pasternak turned to philosophy, eventually enrolling in Germany’s prestigious Marburg University. In 1912, however, Pasternak abruptly left Marburg when his childhood friend, Ida Vysotskaia, rejected his marriage proposal. Deciding to commit himself exclusively to poetry, he eventually joined Centrifuge, a moderate group of literary innovators associated with the Futurist movement. The Futurists advocated greater poetic freedom and attention to the actualities of modern life. Pasternak’s first two poetry collections largely reflect these precepts as well as the influence of Vladimir Mayakovsky, Pasternak’s close friend, who was among the most revered of the Futurist poets.

Pasternak was declared unfit for military service and spent the first years of World War I as a clerical worker. When news of political turmoil reached Pasternak in 1917, he returned to Moscow, but the capital’s chaotic atmosphere forced him to leave for his family’s summer home in the outlying countryside. There he composed Sister My Life: Summer, 1917 (1923). Considered Pasternak’s greatest poetic achievement, this volume celebrates nature as a creative force that permeates every aspect of human experience and impels all historical and personal change. Pasternak’s next poetry collection, Temi i variatsi (1923), solidified his standing as a major modern poet in the Soviet Union. He also received critical acclaim with Rasskazy (1925), his first collection of short stories.

Communism and the Avant-Garde. In 1923, enthusiastic about the possible artistic benefits of the Revolution, Pasternak joined Mayakovsky’s Left Front of Art (LEF), an alliance between Futurist writers and the Communist Party that used the avant-garde movement’s literary innovations to glorify the new social order. His works from this period, Vysockaya bolezn (1924), Deviatsot piatyi god (1926), and Lieutenant Schmidt (1927), are epic poems that favorably portray events leading up to and surrounding the Marxist revolution of 1917. During the late 1920s, Pasternak grew disillusioned with the government’s increasing social and artistic restrictions as well as with Communism’s collective ideal that, in his opinion, directly opposed the individualistic nature of humanity. He eventually broke with the LEF.

Optimism Dashed. The following year, Pasternak divorced his first wife, Evgeniya Lurie, as a result of his affair with Zinaida Neigauz, whom he later married. Critics often cite this new relationship and the couple’s friendships with several Georgian writers as the source of the revitalized poetry found in Vtoroye rozhdenie (1932). A collection of love lyrics and impressions of the Georgian countryside, Vtoroye rozhdenie presented Pasternak’s newly simplified style and chronicled his attempt to reconcile his artistic and social responsibilities in a time of political upheaval. Pasternak’s newfound optimism, however, was subdued following the inception of the Soviet Writers’s Union, a government institution that abolished independent literary groups and promoted conformity to the ideals of socialist realism. Recognized as a major poet by the Communist regime, Pasternak participated in several official literary functions, including the First Congress of Writers in 1934. He gradually withdrew from public life, however, as Joseph Stalin’s repressive policies intensified. He began translating the works of others, including the major tragedies of Shakespeare, rather than composing his own.

Following the publication of Vtoroye rozhdenie, Pasternak reissued several of his earlier poetry volumes under new titles. His new collections of verse, however, did not appear until World War II. Na rannikh poezdakh (1943) and Zemnoy proster (1945) reflect the renewed patriotic spirit and creative freedom fostered by the conflict, while eschewing conventional political rhetoric. Suppression of the arts resumed following the war, and many of Pasternak’s friends and colleagues were imprisoned or executed. Pasternak, who had publicly condemned the actions of the government, escaped Stalin’s purges of the intelligentsia. While some credit his translation and promotion of writers from Stalin’s native Georgia, others report that the dictator, while glancing over Pasternak’s dossier, wrote ‘‘Do not touch this cloud-dweller.’’

Doctor Zhivago. During this dark era, he began work on what became his novel Doctor Zhivago. The exact year in which Pasternak started writing Doctor Zhivago is difficult to establish; scholars Evgenii Pasternak and V. M. Borisov approximate that the novel was started in the winter of 1917-1918. Drawn from Pasternak’s personal experiences and beliefs, the novel utilizes complex symbols, imagery, and narrative techniques to depict Yury Zhivago, a poet and doctor who is caught up in and eventually destroyed by the Communist revolution of 1917. When Pasternak submitted Doctor Zhivago to Soviet publishers in 1956, they rejected the novel for what the editorial board of Novy mir termed its ‘‘spirit ... of nonacceptance of the socialist revolution.’’ Pasternak then smuggled the manuscript to the West, where reviewers hailed the novel as an incisive and moving condemnation of Communism.

The Nobel Prize Debacle In 1959, the Swedish Academy selected Pasternak for the Nobel Prize in Literature, citing his achievements as both a poet and novelist. Nevertheless, the implication that the award had been given solely for Doctor Zhivago launched a bitter Soviet campaign against Pasternak that ultimately forced him to decline the prize. Despite his decision, the Soviet Writers’ Union expelled Pasternak from its ranks, and one Communist Party member characterized the author as a ‘‘literary whore’’ in the employ of Western authorities.

Pasternak published two more works outside the Soviet Union, When Skies Clear (1959), a volume of reflective verse, and Remember (1959), an autobiographical sketch, before his death in 1960. At his funeral, Pasternak was not accorded the official ceremonies normally provided for the death of a member of the Soviet Writers’ Union. Though his funeral was not announced in the official papers, thousands accompanied his family to the grave site, which remains a place of pilgrimage in Russia. In 1987, under the auspices of Communist leader Mikail Gorbachev’s policy of social reform, the Writer’s Union formally reinstated Pasternak, and in 1988, Doctor Zhivago was published in the Soviet Union for the first time.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Pasternak's famous contemporaries include:

Vladimir Mayakovsky (1893-1930): Mayakovsky was a widely read and respected Russian Futurist poet and political agitator and became the archetypal Soviet poet after his death, when Stalin praised his work.

H. P. Lovecraft (1890-1937): Although his short stories of cosmic horror had only a niche following among enthusiasts of ''weird fiction'' during his lifetime, Love- craft's modern take on horror would prove hugely influential with later writers of the supernatural.

Raymond Chandler (1888-1959): Along with Dashiell Hammett, Chandler was the premiere author of "hard- boiled" detective fiction for over two decades. His detective, Philip Marlowe, is perhaps the archetypal private eye.

Anna Akhmatova (1889-1966): Poetically outspoken, Akhmatova's work was often not allowed to be published by the Soviet regime. Her writings circulated via underground networks, and during World War II her patriotic poems inspired her countrymen to fight on. After Stalin's death, Soviet leadership grudgingly acknowledged her place among twentieth century Russian poets.

Agatha Christie (1890-1976): The pen name of Dame Agatha Miller, Christie is the most successful modern author, second only to Shakespeare in terms of volumes sold and breadth of readership. Her 80 mystery novels, especially those featuring her iconic characters Hercule Poirot and Miss Marple, have been translated into dozens of languages and adapted time and again for stage and screen.

Joseph Stalin (1879-1953): From Vladimir Lenin's death in 1924, Stalin ruthlessly consolidated power and became the de facto dictator of the Soviet Union until his own death. His decades as the USSR's leader were marked by political purges on a massive scale, forced deportations, accelerated industrial programs, collectivization of agriculture, and the defeat of Nazi Germany. A cult of personality centered on Stalin extolled him as the savior of the Soviet Union.

Works in Literary Context

Pasternak’s work has an overwhelming and ever-present tendency to penetrate the essential reality of life, whether it is in art, in human relations, or in history. His approach—which consciously avoids everything formal and scholastic—can be termed ‘‘existential’’ in the broadest sense of the term, as a concern with the fundamental problems of existence rather than with systems or ideologies.

Poetry Both Clear and Obscure. Though Pasternak won the Nobel Prize in 1959 for his novel, the Nobel committee first noted his outstanding achievements in verse. He was cited ‘‘for his important achievement both in contemporary lyrical poetry and in the great Russian epic tradition.’’ Pasternak’s mastery of verse was evident in his first complete book of poetry, Twin in the Clouds (1914). This collection reveals a voice of startling originality and, from the point of view of Pasternak’s poetic predecessors, some eccentricity. His verse mixes stylistic registers and introduces colloquialisms, dialect, rarely used words, technical words, and foreign words—even in rhyme. Pasternak’s critical reassessment of his own writings prompted him in 1928 to revise many of the poems from his first two books. He tried to shed them of ‘‘romantic’’ elements, including foreign words, openly autobiographical references, and hyperbolic intonation.

Pasternak’s Clear Vision of Doctor Zhivago. Pasternak did not write Doctor Zhivago for what he called ‘‘contemporary press.’’ He wanted to create something that would slip beneath the systemic control of writers and editors, to write something ‘‘riskier than usual’’ that would ‘‘break through to the public.’’ With this novel, Pasternak wanted to elude censorship and reach truth; in Doctor Zhivago, ‘‘Everything is untangled, everything is named, simple, transparent, sad. Once again, afresh, in a new way, the most precious and important things, the earth and the sky, great warm feeling, the spirit of creation, life and death, have been delineated.’’ With Doctor Zhivago, Pasternak believed he could show ‘‘life as it is.’’

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Pasternak often dwelled on the difficult lot for women in society. Other works that touch upon this theme include:

The Second Sex (1949), a nonfiction work by Simone de Beauvoir. Considered a landmark of feminist literature, this work examines the treatment and perception of women throughout history, particularly how they have been perceived as an aberration of the male sex.

House of Mirth (1905), a novel by Edith Wharton. The title is ironic, for this novel traces the downfall of an independent-minded woman in the stifling high society of America at the turn of the twentieth century.

Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937), a novel by Zora Neale Hurston. An important work for both African- American and women's literature, this novel traces the fate of a black woman living in Florida in the early years of the twentieth century, and her experiences throughout her three marriages.

Works in Critical Context

While his complex, ethereal works often defy translation, Western critics laud Pasternak’s synthesis of unconventional imagery and formalistic style as well as his vision of the individual’s relationship to nature and history. C. M. Bowra asserted: ‘‘In a revolutionary age Pasternak [saw] beyond the disturbed surface of things to the powers behind it and found there an explanation of what really matters in the world. Through his unerring sense of poetry he has reached to wide issues and shown that the creative calling, with its efforts and its frustrations and its unanticipated triumphs, is, after all, something profoundly natural and closely related to the sources of life.’’

Doctor Zhivago Scholarship on Doctor Zhivago appeared entirely outside the Soviet Union until its 1988 publication in Russia. Some early Western studies criticized the novel for its lack of a logical progression of events, its inexplicable use of time, its unbelievable coincidences, and its singleminded language in which only variants of Pasternak’s own voice are present. Evaluations of Doctor Zhivago often disagree as to the novel’s importance. Several critics regarded its many coincidences and Pasternak’s distortion of historical chronology and character development as technically flawed. Other commentators compared Pasternak’s thorough portrayal of a vast and turbulent period to that of nineteenth-century Russian novelists, particularly Leo Tolstoy. Additionally, the major themes of the novel, often distilled in the poems attributed to the title character, have been the subject of extensive analysis. Through Zhivago, critics maintain, Pasternak realizes his vision ofthe artist as a Christ-like figure who bears witness to the tragedy of his age even as it destroys him. This idea is often linked to Pasternak’s contention that individual experience is capable of transcending the destructive forces of history. It is this concept, commentators assert, that gives Doctor Zhivago its enduring power. Marc Slonim observed: ‘‘In Doctor Zhivago man is shown in his individual essence, and his life is interpreted not as an illustration of historical events, but as a unique, wonderful adventure in its organic reality of sensations, thoughts, drives, instincts and strivings. This makes the book ... a basically anti-political work, in so far as it treats politics as fleeting, unimportant, and extols the unchangeable fundamentals of human mind, emotion and creativity.’’ In memoirs he kept during the mid-1960s, Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet premier who suppressed the novel in 1956, concluded: ‘‘I regret that I had a hand in banning the book. We should have given readers an opportunity to reach their own verdict. By banning Doctor Zhivago we caused much harm to the Soviet Union.’’

Sister My Life: Summer, 1917 Often uniting expansive, startling imagery with formal rhyme schemes, Sister My Life: Summer, 1917 is marked by the spirit of the revolution and marks a synthesis of the principal poetic movements of early twentieth-century Russia, including the Futurists, the Acmeists, and the Imagists. De Mallac suggested that it was Pasternak’s ‘‘sincere endeavor to apprehend the era’s political turmoil, albeit in a peculiar mode of cosmic awareness.’’ Robert Payne commented in The Three Worlds of Boris Pasternak that the author’s ‘‘major achievement in poetry lay ... in his power to sustain rich and varied moods which had never been explored before.’’

Responses to Literature

1. The Nobel Prize for Literature is normally the most coveted award for any writer to achieve, yet for Pasternak it only served to increase his paranoia. With a group of classmates, discuss why you think this is. Why do you think only one other Russian author publicly congratulated him?

2. The character of Lara in Dr. Zhivago is subjected to pressures both internal and external. Write an essay in which you explore how her own emotional demons affect her, and how her inner turmoil differs from the stresses placed on her by external political forces.

3. With a classmate, research Stalin’s rise to power and his totalitarian regime on the Internet or in your library. Create a report for the class in which you describe how Stalin’s approach to personal and political freedom is reflected in the particular text by Pasternak’s that you have read. Use examples from the text to support your ideas.

4. Write a 5-7-page essay on how you think Pasternak’s background as a poet influenced his literary style in Dr. Zhivago. Use examples from the text, as well as from Pasternak’s poetry, to support your ideas.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Bowra, C. M. ‘‘Boris Pasternak, 1917-1923.’’ Discovering Authors. Online ed. Detroit: Gale, 2003.

Clowes, Edith W. Doctor Zhivago: A Critical Companion. Evanston, 1ll.: Northwestern University Press, 1995.

Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 302: Russian Prose Writers After World War II. A Bruccoli Clark Layman Book. Edited by Christine Rydel, Grand Valley State University. Detroit: Gale, 2004.

Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 331: Nobel Prize Laureates in Literature, Part 3: Lagerkvist-Pontoppidan. A Bruccoli Clark Layman Book. Detroit: Gale, 2007.

Erlich, Victor, ed. Pasternak: A Collection of Critical Essays. Englewood Cliffes, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1978.

Fleishman, Lazar. Boris Pasternak: The Poet and His Politics. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1990.

Gladkov, Alexander. Meetings With Pasternak: A Memoir. Trans. and ed. with notes and introduction by Max Hayward. New York: Harcourt, 1977.

Hughes, Olga Raevsky. The Poetic World of Boris Pasternak. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1974.

‘‘Overview of Boris (Leonidovich) Pasternak.’’ DISCovering Authors. Online ed. Detroit: Gale, 2003.

‘‘Pasternak, Boris (Leonidovich) (1890-1960).’’ DISCovering Authors. Online ed. Detroit: Gale, 2003.

Pastermak, Evgeny. Boris Pastermak: The Tragic Years 1930-1960. London: Collins Harvell, 1990.

Poggioli, Renato. ‘‘Poets of Today.’’ DISCovering Authors. Online ed. Detroit: Gale, 2003.

Rudova, Larissa. Pasternak’s Short Fiction and the Cultural Vanguard. New York: P. Lang, 1994.

________. Understanding Boris Pasternak. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1997.

Sendich, Munir. Boris Pasternak: A Reference Guide. New York: Macmillan, 1994.

‘‘Study Questions for Boris (Leonidovich) Pasternak.’’ DISCovering Authors. Online ed. Detroit: Gale, 2003.