World Literature

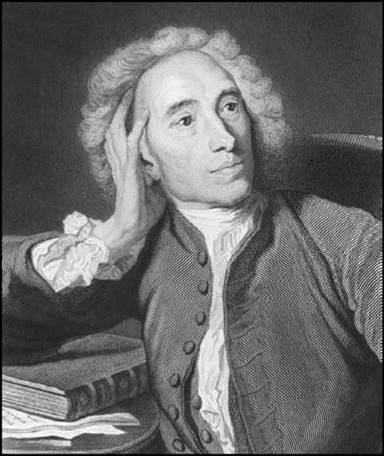

Alexander Pope

BORN: 1688, London, England

DIED: 1744, London, England

NATIONALITY: British

GENRE: Poetry, criticism

MAJOR WORKS:

An Essay on Criticism (1711)

The Rape of the Lock (1714)

The Dunciad (1728)

Moral Essays (1731-1735; collected 1751)

An Essay on Man (1733)

Alexander Pope. Hulton Archive / Getty Images

Overview

Alexander Pope was a superstar of English neoclassical literature, so much so that the first half of the British eighteenth century is often referred to as ‘‘the age of Pope.’’ Pope alternately defined, invented, satirized, critiqued, and reformed almost all of the genres and conventions of early-eighteenth-century British verse. He polished his work with meticulous care, and he is generally recognized as the greatest English poet between John Milton and William Wordsworth.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

A Catholic Exile. Pope’s Roman Catholic father was a linen merchant. After a line of Catholic monarchs was excluded from England in the Glorious Revolution of 1688, Catholics were barred from living within the city of London, and Pope’s family moved to Binfield in Windsor Forest. Pope had little formal schooling, largely educating himself through extensive reading. He contracted a tubercular infection in his later childhood; tuberculosis is a highly contagious disease that generally causes damage to the lungs but can also affect other areas, such as the spine, as it did in Pope’s case. Tuberculosis was a widespread concern in Pope’s time, since effective treatments for the disease were still two centuries away, and half of those who developed full-blown symptoms would eventually die. Pope lived, but because of his illness, he never grew taller than four feet six inches, suffering from curvature of the spine and constant headaches. His physical appearance, frequently mocked by his enemies, undoubtedly gave an edge to Pope’s satire, but he was always generous in his affection for his parents and many friends.

Early Poems. Pope was a child prodigy. His first publication, Pastorals (1709), drew on long-established literary conventions but nevertheless announced him as a major new talent. Pope’s next major work, An Essay on Criticism (1711), was much bolder. In the work, Pope finds modern literature largely failing in its responsibility to follow unchanging ‘‘nature,’’ the test of which is how well we can recognize basic human truths in ancient classical works (particularly Homer). An Essay on Criticism became the manifesto for a major movement in literary criticism: neoclassicism. Pope wrote the entire essay in heroic couplets (pairs of rhymed iambic pentameter lines).

One year later, Pope surprised many by showing he was also a master of humor and satire with The Rape of the Lock (1712, two cantos), which immediately made Pope famous. A fashionable young lady, Arabella Fermor, had a lock of her hair cut off without permission by a suitor, and Pope was asked by a mutual friend to soothe ruffled tempers with a jest. Adopting a mock-heroic style that drew upon Homer and others (who were valorized so seriously in An Essay on Criticism), Pope showed how ridiculous it was to treat the event overseriously and simultaneously satirized the vanity and glitter of upper- class society.

Other poems published by 1717, the date of the first collected edition of Pope’s works, include ‘‘Windsor Forest’’ (1713), which showed Pope as an ‘‘occasional’’ poet, or one who writes about current events. The collection also included Eloisa to Abelard, which shows Pope’s turning to a new genre, love poetry.

Translations of Homer. Pope’s study of, and high regard for, classical literature led him naturally to the art of translation. He had already done poetic imitations, transformations, or translations of Vergil, the Bible, and Chaucer, but his versions of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey were his greatest achievement as a translator and, some say, a poet. Pope not only translated Homer’s Greek into English, but also recast the lines into powerful, expressive, and flexible heroic couplets.

Pope’s translations sold well, making him one of England’s first full-time, self-supporting poets. Unlike Edmund Spenser (1552-1599), who was arguably England’s first professional writer, Pope was the first poet to become wealthy. In 1716, an increased land tax on Roman Catholics forced the Popes to sell their place at Binfield, but after Pope’s father died in 1717, Pope and his mother moved to an expansive villa outside London. He had gardens built there that became famous through out Europe, complete with an underground grotto decorated with shells and bright stones.

During these years, Pope became friends with some brilliant writers, including Jonathan Swift, Dr. John Arbuthnot, John Gay, and Thomas Parnell. Together they combined to form the Scriblerus Club, and they planned a series of satires against narrow-minded academics and the popular culture’s fascination with ‘‘novelty.’’ Together they published The Memoires of Martinus Scriblerus (1741), and their discussions contributed to the creation of Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726) and Pope’s The Dunciad.

The Dunciad. One of the editorial projects Pope undertook was an edition of Shakespeare’s plays (1725). Pope’s explanatory notes were uneven, and the edition was attacked by a rival Shakespeare editor, Lewis Theobald. Pope, never one to forget or forgive criticism, made Theobald the head of all dunces in a mock-epic tour de force of bitterly satirical couplets. The Dunciad (the title is a pun on Homer’s epic The Iliad) appeared in 1728. A year later the text increased to include a large collection of notes and commentaries intended as a burlesque on the heavy labor of commentators and textual critics. Pope used The Dunciad to settle old scores and to show his distaste for a literary culture that would come to be known as ‘‘Grub Street’’; on ‘‘Grub Street,’’ writers competed with one another to appeal to the lowest tastes of the reading public, which often resulted in untalented and irresponsible writers gaining undeserved literary prominence.

The Epistles and An Essay on Man. Late in his life, Pope undertook a series of satires in the classical sense of the term, a collection of serious and sardonic commentaries of culture and ethics. These satires took the form of letters (or ‘‘epistles’’) to his close friends. For example, ‘‘The Epistle to Burlington’’ (1731) illustrates, along with its companion piece ‘‘Epistle to Bathurst’’ (1733), the right and wrong way to use wealth as well as the parallels between artistic taste and moral virtue.

An Essay on Man is Pope’s most philosophical work and in some ways his most ambitious. Pope’s argument views religion through the lens of the emerging eighteenth-century Enlightenment: seeing God as a rational and balanced creator who, by nature, ensures that everything happens as part of a carefully organized universal plan. ‘‘All Nature is but Art, unknown to thee; / All chance, direction, which thou canst not see / All discord, harmony not understood, / All partial evil, universal good,’’ Pope writes. Pope also revives the ancient idea of the ‘‘great chain of being,’’ the idea that all species in creation are ranked in a hierarchy with God and the angels at the top, Man in the middle, and the simple organism at the bottom. Presuming for ourselves the authority to blame God for when things do not go our way, Pope says, is therefore an absurd and blasphemous act of pride for stepping out of our place on the chain. In essence, An Essay on Man is not so much philosophy or theology, but a poet’s apprehension of unity despite diversity, of an order embracing the whole multifarious creation—a theme that finds expression in Pope’s works as various as the Pastorals, The Dunciad, and ‘‘An Epistle to Burlington.’’

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Pope's famous contemporaries include:

Christian Wolff (1679-1754): A philosopher who embodied the Enlightenment ideal in Germany, Wolff is regarded as the inventor of economics and public administration as fields of academic study, and his ideas influenced the American Declaration of Independence.

George Frideric Handel (1685-1759): A German-born composer who later relocated to England, Handel is most famous for his oratorio The Messiah, composed in 1741.

George Berkeley (1685-1753): Berkeley, an Irish philosopher who promoted the idea of "immaterialism," also contributed to the development of calculus.

John Harrison (1693-1776): This English clockmaker who invented the marine chronometer, a device that accurately determined the longitudinal position of a ship, won a huge prize offered by the British Parliament and made voyages to the New World safer and more efficient.

Charles-Louis de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu (1689-1755): This French social and political commentator promoted the separation of government powers, an idea that became a cornerstone of the American Constitution.

Works in Literary Context

Pope and Neoclassicism. Pope, particularly in An Essay on Criticism and ‘‘Epistle to Arbuthnot,’’ contributed to neoclassicism, or the resurgence in ancient ideals in art and literature—particularly the ideals of ancient Greece and Rome. For Pope, the core truth is whatever has lasted longest across many generations of readers; thus we should look to ancient literature for truth. In the epics of Homer, for example, the ethics of heroism, loyalty, and leadership are as true now as they were then. In addition, the balanced and symmetrical structures of classical literature and architecture represent values of reason and coherence that Pope says should remain central to all modern arts.

Comic Satire. Pope used his great knowledge of and respect for classical literature to write mock-epics that poked fun at the elite. Essentially Pope believed the upper class possessed an exaggerated sense of its own importance. He also made fun of hack writers, comparing their shoddy work with timeless stories of the past. Pope is credited for proclaiming, ‘‘Praise undeserved is satire in disguise.’’

Pope and Proverbs. Pope’s style and personal philosophies have become part of the English language. For example, ‘‘A little learning is a dang’rous thing’’ comes from An Essay on Criticism, as does ‘‘To err is human, to forgive, divine.’’ Other well-known sayings from An Essay on Criticism include ‘‘For fools rush in where angels fear to tread’’ and ‘‘Hope springs eternal.’’

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

When tragedy strikes, people of faith often question how a just and good God could allow it to happen. Pope, who had crippling physical ailments and chronic pain for his entire adult life, worked out his own theories in An Essay on Man. Many other authors have tackled these difficult questions with alternate answers.

In the Buddha's Words: An Anthology of Discourses from the Pali Canon (2005). Selected teachings of the Buddha from the Pali Canon, the earliest record of what the Buddha taught, from truths on family life and marriage to renunciation and the path of insight.

The Metamorphosis (1915), a novella by Franz Kafka. In this classic existentialist work, a man wakes up one day and finds he has been transformed into a human-sized dung beetle. No explanation is given, no lessons are learned, and no redemption is given.

When Bad Things Happen to Good People (1983), a nonfiction book by Harold S. Kushner. In this controversial best seller written by a Jewish rabbi facing the death of his own child, Kushner offered a theory that God does not necessarily control everything that happens in his creation.

Works in Critical Context

Pope’s enormous success attracted a great deal of jealousy within the already competitive and vindictive London literary scene. Pope’s Catholicism, his conservative politics, and his unusual physical appearance made the literary public even more envious. Pope remembered every literary critic who dared to disapprove of his work or mock his physical appearance, and decades after someone printed a bad review of Pope’s poetry, a critic might find their name in the parade of fools in The Dunciad. Not satisfied with the level of attack in that work, which was enough to ruin the career of more than one writer, Pope followed it a year later with The Dunciad, Variorum, which added mock-scholarly footnotes naming names of even more of the disfavored literary critics and hack writers who, Pope believed, were dragging down the dignity of the entire literary profession and endangering the moral foundation of society.

Pope in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. After his death in 1744, few had anything but the highest praise for Pope’s poetic achievement. Joseph Warton and Samuel Johnson, perhaps the most influential critical voices in the late eighteenth century, secured his place in the literary canon. For the Romantic critics of the early nineteenth century, however, Pope was often seen more as a fine poetic craftsman who nevertheless preferred topical satire and petty themes to the higher (to Romantics, anyway) poetic subjects of the natural world and confessional passions. As the mid-nineteenth-century Victorians sought to distinguish themselves with a high moral tone in contrast to their somewhat more coarse and outspoken eighteenth-century ancestors, Pope was respected but largely neglected.

New Critics. The New Critics of the mid-twentieth century revived interest in Pope with their emphasis on high literary technique, irony, and the poetic rewards of close reading. A definitive edition of Pope’s works in 1963 and a thorough biography by Maynard Mack in 1985 brought about many new enthusiastic and often biographically based interpretations of Pope’s work. In recent years, Pope’s collected poetry has proven a rich resource for cultural critics interested in all aspects of early eighteenth-century values and culture, particularly the influence of colonial ideologies, the role of gender in the poet’s imagination, the impact of an emerging print culture, the new emphasis on materialism, and the complex interactions of religion and politics as the Restoration moved into the early eighteenth century.

Responses to Literature

1. Pope did not often appreciate it when other people wrote about him, but he wrote often about himself. Particularly in the ‘‘Epistle to Arbuthnot,’’ how does Pope portray himself? What is Pope’s image of himself and the conditions of his own life? Jot down a paragraph summarizing your findings.

2. For all of the satire in The Rape of the Lock, it is often said that a tone of admiration and even longing resonates in the way Pope portrays the kind of upper-class society from which he was excluded as a Catholic, a poet, and the son of a linen merchant. With a classmate, discuss whether you agree or disagree. Then, discuss whether you think Pope manages to balance or combine his admiration of Belinda and her friends with his satire of them. Point out specific lines from the text to support your ideas.

3. Do some research into the style of gardens in the eighteenth century. Create an audiovisual report discussing why you think landscaping means more than just a pleasing arrangement of plants. Then, research the way Pope made contributions to the theories of gardening during his lifetime, as well as the plants or forms he incorporated into his own garden. Add your findings about Pope to your presentation.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Boyce, Benjamin. The Character-Sketches in Pope’s Poems. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1962.

Brown, Laura. Alexander Pope. Oxford, England: Blackwell, 1985.

Brownell, Morris. Alexander Pope and the Arts of Georgian England. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press, 1978.

Damrosch, Leopold. The Imaginative World of Alexander Pope. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1987.

Fairer, David. Pope’s Imagination. Manchester, England: Manchester University Press, 1984.

Griffin, Dustin M. Alexander: The Poet in the Poems. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1978.

Jones, John A. Pope’s Couplet Art. Athens: Ohio University Press, 1969.

Mack, Maynard. Alexander Pope: A Life. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1985.

________. Collected in Himself: Essays Critical, Biographical, and Bibliographical on Pope and Some of His Contemporaries. Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1982.

________, ed. Essential Articles for the Study of Alexander Pope. Hamden, Conn.: Archon, 1968.

Rogers, Pat, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Alexander Pope. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

Sitter, John. The Poetry of Pope’s Dunciad. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1971.

Spacks, Patricia. An Argument of Images: The Poetry of Alexander Pope. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1971.

Tillotson, Geoffrey. Pope and Human Nature. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press, 1958.

White, Douglas H. Pope and the Context of Controversy: The Manipulation of Ideas in An Essay on Man. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970.

Jean-Baptiste Poquelin

SEE Moliere