World Literature

Marcel Proust

BORN: 1871, Auteuil, France

DIED: 1922, Paris, France

NATIONALITY: French

GENRE: Fiction, nonfiction

MAJOR WORKS:

Remembrance of Things Past (1913-1927)

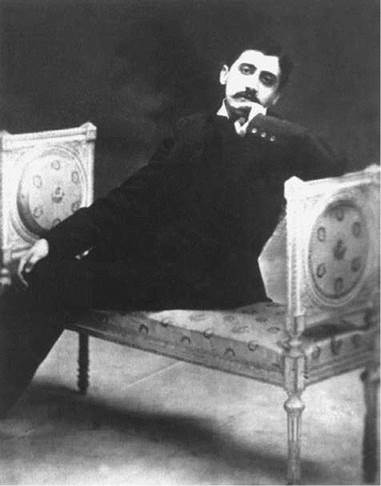

Marcel Proust. Proust, Marcel, photograph. AP Images.

Overview

Marcel Proust is known primarily for his multivolume novel Remembrance of Things Past, regarded as one of the most important works of twentieth-century literature. A philosophical meditation on the nature of time and consciousness, Proust’s masterpiece offers profound psychological insights into the complicated human soul. In addition, the novel provides a social chronicle of turn-of- the-century Parisian society.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

Family and Early Life. Marcel Proust was born July 10, 1871, in Auteuil, France, to Adrien, a prominent medical doctor, and Jeanne Weil Proust. His mother was Jewish and later converted to Christianity. Proust attended L’Ecole libre des sciences politiques, graduating in 1890, and the Sorbonne, University of Paris, where he received his bachelor’s degree in 1895. Although he suffered severely from asthma, he completed a year of military service in 1889-1890.

Proust was homosexual at a time when it was not spoken of openly, and he sought to hide this part of himself from public view. Before World War I, he was emotionally involved with Alfred Agostinelli, who was killed in an airplane crash in 1914. The extent of his relationships with other men is unknown.

Early Work. In the mid-1890s, Proust was chiefly known as a contributor of short prose to various Paris reviews. In an important work of criticism published posthumously, By Way of Sainte-Beuve (1954), Proust presented his conception of literature. Charles Saint-Beuve was a major critic who viewed literature as an expression of the author’s life experiences. On the contrary, Proust argued that the author transcends the historical and biographical in the process of writing. He called on writers to create a new literature of impressions by which they convey their subjective selves. These impressions were to be based on involuntary memories, such as those springing from taste and sound.

In 1895 he was appointed to the library of the Institut de France. He seldom performed his duties, annually asked for leave on the pretext of bad health, and was finally dismissed in 1900. Proust’s real interest during all of this time was society, which he would examine in his literary masterpiece.

On September 26, 1905, his mother died. While Proust had previously published one novel and abandoned work on another, one of the debts that he felt he owed his mother was to write a great work of literature.

Remembrance of Things Past. Started in 1909, Remembrance of Things Past originally appeared in seven volumes, three of which were not published until after Proust’s death. He never finished revising these final volumes. Swann’s Way, the first volume of Remembrance of Things Past, was published in 1913. Like the other volumes in the series, it is a complete novel in itself. It introduces the many themes and motifs—such as memory, jealous love, social ambition, homosexuality, and the importance of art—that are developed in later volumes. It was greeted with hostility because of the complexity of Proust’s style.

The second volume, Within a Budding Grove, was published in 1919. Volume three, The Guermantes Way (1920), won a national literary prize and brought Proust international recognition. Cities of the Plain (1922) explores the themes of homosexuality and corruption.

For most of his last fifteen years, Proust lived as an invalid. He died of a lung infection on November 18, 1922, in Paris.

Three more volumes of Remembrance of Things Past were published after his death. The Captive (1923) and The Sweet Cheat Gone (1925), the fifth and sixth volumes of the series, were not included in Proust’s original plan for Remembrance of Things Past, and some critics believe that events in Proust’s personal life led him to expand his novel to include the themes of jealous love and deception.

Time Regained (1927), the final volume, successfully ties together all of the novel’s recurrent themes and motifs. In Time Regained, the narrator realizes that memory is the key to the meaning of the past that he has been seeking and that art has the ability to redeem experience from disillusionment, deception, and the decay of time.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Proust's famous contemporaries include:

Colette (1873-1954): A French writer who scandalized the public with her affairs with both men and women. Her novels included semiautobiographical elements.

Anatole France (1844-1924): French writer, considered a master of irony. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1921.

Rosa Luxemburg (1870-1919): Jewish German political revolutionary who cofounded what became Germany's Communist Party. She was revered by many Marxists and killed by German monarchist soldiers.

Thomas Mann (1875-1955): German novelist awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1929. He was well known for his novels Buddenbrooks and The Magic Mountain.

Emile Zola (1840-1902): French novelist who was influential in the school of naturalism, which sought to portray life realistically.

Works in Literary Context

Remembrance of Things Past continues the traditions both of the great seventeenth-century classical writers such as Madame de La Fayette, the Duc de Saint-Simon, and the Duc de La Rochefoucauld, and of the nineteenth-century realists such as Stendhal, Honore de Balzac, and Gustave Flaubert. At the same time, it is highly innovative in technique and content.

Marcel Proust was influenced by the British critic and writer John Ruskin who used complicated sentence structures to capture the impressions and experiences furnished by art and nature. Proust translated several of Ruskin’s works, although he objected to the writer’s moralizing on works of art.

In Time Regained, the final novel of Remembrance of Things Past, the narrator rejects realism and acknowledges his literary ancestors: founder of French Romanticism Chateaubriand, the Romantic French poet Gerard de Nerval, and the poet Charles Baudelaire, famous for his Flowers of Evil.

The Importance of Memory. One of the most important elements throughout the entire series of novels is memory and its necessity in the creation of art. The translation of the series’ title in French, In Search of Lost Time, reflects the author’s close association of time and memory, with memories being the tangible legacy of past times and experiences. This is shown most dramatically when Marcel eats a madeleine, a sensory experience that draws him into a world of memory.

Works in Critical Context

In 1936, Proust scholar Leon Pierre-Quint claimed that the fashion for Remembrance of Things Past had ended and that Marcel Proust was destined to interest only thesis writers at the Sorbonne. He could not have been more mistaken, for Proust today is almost universally revered as the greatest French author of the twentieth century.

Criticism from the 1970s and 1980s, in addition to a wealth of biographical and critical material from previous decades, attests to the multiple approaches one can take to Proust’s work. While textual scholarship is still being pursued, the most recent critical examinations have tended to emphasize either narrative technique or psychological content.

Proust as Narrative Innovator. Proust is seen as a great narrative innovator; his manipulations of narrative time and voice, for example, are an early instance of techniques later used by certain New Novelists, as Gerard Genette showed in Narrative Discourse: An Essay on Method, and Proustian technique contributed to creating a new conception of story line and narrator. Other critics view Proust as one of the most creative psychologists of the self; Serge Doubrovsky, in Writing and Fantasy in Proust, has shown how Proust used language and metaphor to conceal and reveal at once the most intimate obsessions of his psyche.

One of the most important issues in Proust criticism is the role of the character Marcel as protagonist and narrator of Remembrance of Things Past and his relationship to Proust himself. There is strong evidence for both identifying Proust with Marcel and for separating the two, and some interpretations of the novel are more autobiographical than others. Perhaps the firmest ground for likening Proust with Marcel is their mutual struggle to realize themselves as artists, with each making art the highest value in their lives. For both, the search for lost time ends in the disillusioned abandonment of life and in the affirmative re-creation of life as a work of art.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

In Marcel Proust's masterpiece, memory becomes a means of transcending change and death; involuntary memory can transport individuals through time. He finds affirmation in the recreation of life as a work of art. Here are some other works that deal with similar themes:

House of Incest (1936), a novella by Anais Nin. ''Incest'' here is a metaphor for loving only one's own qualities in another; this surrealistic novel investigates reality by delving into the subconscious.

The Lost World (1965), poetry by Randall Jarrell. This volume of poetry, published posthumously, was inspired by letters Jarrell wrote to his mother as a child and reshapes his childhood memories.

Native Guard (2007), poetry by Natasha Tretheway. These poems examine the author's heritage as a multiracial southerner; the ten sonnets of the title poem tell the story of a Civil War soldier in an all-black regiment and reveal the circularity of life.

Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916), a novel by James Joyce. This semiautobiographical novel follows the young Stephen Dedalus as he questions his religious upbringing and leaves his native Ireland to become an artist.

The Waves (1931), a novel by Virginia Woolf. This novel, following six friends through their lives, is freed from narrative time and explores change and metamorphosis.

Responses to Literature

1. Charles Saint-Beuve argued that literature is ‘‘an expression of the author’s life experiences.’’ What does that mean? Write an essay analyzing the meaning of that statement and arguing for or against that point of view.

2. Think about memory as a key to the meaning of the past. Write two or three paragraphs about a significant event in your life. Then rewrite it from someone else’s point of view. How does what you choose to reveal in each version influence the reader’s perception of what happened?

3. In Remembrance of Things Past, the narrator famously eats a madeleine, a type of cookie, that transports him to his past. Listen to some music that was important to you several years ago. Write two or three paragraphs describing your memory of listening to it before. Be specific—what clothes were you wearing, where were you, who were you with?

4. Marcel Proust argued that people could re-create their lives as works of art. Using the Internet and your library’s resources, research other artists who have attempted similar projects—such as Andy Warhol, the New York artist. Write an essay discussing how Warhol or another artist tried to make his or her own life into a work of art.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Aciman, Andre. The Proust Project. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2004.

Albaret, Celeste. Monsieur Proust. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1976.

Botton, Alain de. How Proust Can Change Your Life; Not a Novel. New York: Pantheon, 1997.

Bowie, Malcolm. Proust among the Stars. New York: Columbia University Press, 1998.

Fraser, Robert. Proust and the Victorians: The Lamp of Memory. New York: St. Martin’s, 1994.

Henry, Anne. Marcel Proust: Theories pour une esthetique. Paris: Klincksieck, 1981.

Nalbantian, Suzanne. Aesthetic Autobiography: From Life to Art in Marcel Proust, James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, and Anais Nin. New York: St. Martin’s, 1994.

Paganini-Ambord, Maria. Reading Proust: In Search of the Wolf-Fish. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 1994.

Shattuck, Roger. Proust’s Way: A Field Guide to In Search of Lost Time. New York: Norton, 2000.

Periodicals

Ortega y Gasset, Jose. ‘‘Time, Distance, and Form in Proust.’’ Hudson Review 11 (Winter 1958/1959): 504-13.

Web Sites

Bender, Marilyn. Paris: Proust’s Time Regained. Retrieved May 27, 2008, from http://www.nysoclib.org/travels/proust.html. Last updated on July 15, 1997.

Calkins, Mark. A la recherche du ‘‘Temps Perdu.’’. (In English) Retrieved May 27, 2008, from http://www.tempsperdu.com. Last updated on June 7, 2007.

Ford, Daniel. Reading Proust. Retrieved May 27, 2008, from http://www.readingproust.com. Last updated June 2008.