World Literature

Jose Saramago

BORN: 1922, Azinhaga, Portugal

NATIONALITY: Portuguese

GENRE: Novels, drama

MAJOR WORKS:

Blindness (1995)

All the Names (1997)

The Double (2004)

Seeing (2006)

The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis (1984)

The Stone Raft (1986)

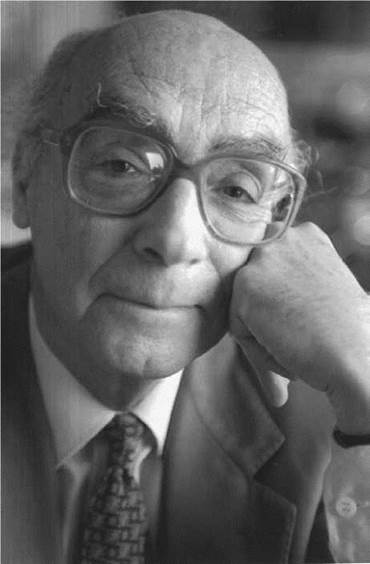

Jose Saramago. Saramago, Jose, photograph. AP Images.

Overview

Jose Saramago is a Portuguese author of fiction, poetry, plays, and essays. An accomplished writer and storyteller, he is most highly regarded for his novels, which vary in theme and subject matter and tend to explore the values and priorities in modern society. Saramago, an outspoken Communist and atheist, is known as the voice of the common person, a role he undertakes with newspaper and radio commentaries as well as in his fiction. He is the first Portuguese-language author to win the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

A “Wild Radish’’ of Portugal. Jose Saramago was born on November 16, 1922, to Jose; de Sousa and Maria de Piedade in the provincial town of Azinhaga, Portugal. ‘‘Saramago,’’ which is Portuguese for ‘‘wild radish,’’ was actually a nickname of his father’s family, and it was accidentally included in his name in the registry of births. In 1924, the family moved from the province to the city of Lisbon, which gave Saramago the rare opportunity to receive an education. While in school, where he excelled in all of his subjects, he made time for his grandfather’s farm back in Azinhaga, helping to take care of the land. After attending Lisbon’s grammar schools, unfortunately, Saramago was forced to drop out due to the family’s dwindling finances.

During his teen years, Saramago attended a technical school for mechanics that offered other academic courses on the side. Saramago took full advantage of the opportunity and studied literature and French with the aim of mastering the art of literary translator. Though he never finished formal schooling, he later obtained several honorary doctorates from various universities.

In 1944, Saramago met Ilda Reis, one of Portugal’s best engravers, and they had one daughter, Violante. While working mechanical jobs, he wrote and published a short novel, Land of Sin. He later traded in his mechanical jobs and worked as an editor for a small Lisbon newspaper. When he lost his job, he turned to translating French manuscripts, and it was not long before he returned to writing his own stories.

Literary Success. In 1977, Saramago published what he considers to be his first novel, Manual of Painting and Calligraphy. This was followed by two more books in quick succession: Quasi Objects (1978) and Raised from the Ground (1980). Raised from the Ground was well received in literary circles and in the press, earning Saramago some degree of recognition. His 1982 novel, Memorial do convento translated into English as Baltasar and Blimunda, was the first of his works to be translated and is often ranked foremost among his artistic triumphs.

During the 1980s, Saramago dedicated his time to several more novels: The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis released in 1984, The Stone Raft (1986), and The History of the Siege of Lisbon (1989).

Offending the Church. In 1991, Saramago published The Gospel According to Jesus Christ, a novel that was condemned by the Catholic Church. Portugual’s conservative government contested the novel’s entry into the running for the European Literary Prize under the pretext that the book was offensive to Catholics. Saramago and his second wife, whom he married in 1988, left Lisbon and moved to Lanzarote in the Canary Islands. In 1995, he published the novel Blindness and in 1997 All the Names. His hard work and perseverance paid big dividends as he went on to win several awards, including the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1998, cementing his reputation as one of Europe’s most highly regarded literary figures.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Saramago's famous contemporaries include:

Gabriel Garcia Marquez (1927-): Hailing originally from Colombia, Garcia Marquez is one of Latin America's most famous authors; he was recognized for his contribution to twentieth century literature in 1982 when he was awarded the Nobel Prize.

Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986): This Argentine author was one of Latin America's most original and influential prose writers and poets; his short stories revealed him as one of the great stylists of the Spanish language.

Harold Pinter (1930-): English playwright and author of The Birthday Party who received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2005.

Julio Cortazar (1914-1984): Argentine author famous for his influential postmodern novels and stories, especially Hopscotch (1963).

Works in Literary Context

Although Portuguese is spoken in three continents by between 140 million and 200 million people, Saramago was the first writer in that language to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. In 1998, the Nobel Committee presented the award to the seventy-four-year-old Saramago, ‘‘who with parables sustained by imagination, compassion and irony continually enables us once again to apprehend an elusory reality,’’ according to the official Nobel Foundation Web site.

Free-Flowing Prose

With his engaging storytelling and a unique style of writing, Saramago has carved himself a niche as one of Europe’s most important literary figures. Saramago uses a distinctive narrative voice that is undeniably his own. Stylistically, he uses run-on sentences and pages of endless paragraphs, refusing to follow conventional rules of punctuation. Thematically, he balances dread and hope and portrays human resilience amid unbearable misery.

Fantasy and Parable

Saramago’s works often rely upon fantastic elements to tell a tale that illustrates a point or delivers a message. In The Stone Raft, for example, the peninsula that contains Spain and Portugal breaks free from Europe and begins drifting across the Atlantic Ocean. In The Year of the Death of Ricardo Reis, a fictional persona of Portuguese poet Fernando Pessoa continues living after the poet himself has died. In Blindness, nearly all the citizens of an unspecified city are struck by a plague that results in blindness; the novel deals largely with the aftermath, and how the afflicted adjust to a society without sight. In each of these tales, the setting is clearly a realistic world in which an element of fantasy has been introduced.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Identity formation, or the way in which an individual comes to distinguish his or herself as a separate entity, is a key theme explored in Saramago's novel The Double. Other works that explore this theme include:

The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (1759-1767), a novel by Laurence Sterne. Considered by some to be the first postmodern novel, this work purports to tell the story of the protagonist's life, although Tristram struggles to explain himself so much so that the telling of his birth is not reached until the third volume of the work.

Invisible Man (1952) a novel by Ralph Ellison. This story is about the travels of a narrator, a nameless African American. In the novel, Ellison explores the influences of various cultural and political forces, particularly with regard to race, on identity formation.

Identity (1998), a novel by Milan Kundera. In this short work, Kundera explores the questions of identity within the context of romantic love.

Works in Critical Context

Through the years, Jose Saramago’s works have had a place in Portuguese—and European—literary history, starting with Raised from the Ground, which was one of Saramago’s first works to earn considerable literary recognition in Portugal. With regard to Blindness, Andrew Miller of the New York Times Book Review has called it ‘‘a clear-eyed and compassionate acknowledgment of things as they are, a quality that can only honestly be termed wisdom.’’ The novel helped Saramago gain the respect of readers and critics alike, laying the foundation for the awards he received later. The Library Journal, meanwhile, praised All the Names, saying it is ‘‘in turns claustrophobic, playful, farcical, and suspenseful.’’ The world immediately took notice of Saramago’s unique writing talent, which won him the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1998.

The Double. Critical reception of the novel The Double was also favorable, with Merle Rubin of the Los Angeles Times praising the way it ‘‘[intrigues] us, proceeds to entertain, charm and engage, and ultimately manages to disturb.’’ Amanda Hopkinson, writing for The Independent, even called it ‘‘his most practiced and polished’’ work, that it is ‘‘philosophy and thriller rolled into one with—as ever—a tight cast of characters.’’ Finally, Philip Graham of the New Leader considers it as ‘‘a deft reworking of a timeless theme and a virtuoso exercise in voice— from a writer who seems to produce masterpiece after masterpiece like clockwork.’’

Seeing. Seeing also gained the respect of critics, although some thought that its storytelling ‘‘is so hazy that it’s hard to see the point,’’ according to Troy Patterson of Entertainment Weekly, and that, in the words of Publishers Weekly, ‘‘[t]he allegorical blindness/sight framework is weak and obvious.’’ Jack Shreve of Library Journal countered by saying that ‘‘Saramago’s clear eye for acknowledging things as they are barrages us with valuable insights suggesting that the dynamics of human governance are not as rational as we like to think.’’ Also, Sarah Goldman of Salon maintains that Saramago ‘‘is a deliberate, attentive writer; he knows exactly what his words mean, and all of them— despite what he may have thought more than a halfcentury ago—are completely worthwhile.” Finally, Julian Evans of The Independent recalled that no novel has told more ‘‘with such arresting humor and simplicity, about the imposture of the times we live in’’ as Seeing did.

Responses to Literature

1. What questions does Saramago’s The Double raise about identity while following Tertuliano Maximo Afonso’s search for his double? Cite specific examples from the novel.

2. Discuss the role of namelessness in Blindness. How is namelessness important to the theme?

3. What role does ‘‘stream of consciousness’’ play in Blindness? Why does Saramago choose this particular technique to include in this work?

4. How does Saramago’s unconventional use of sentence structure and punctuation affect you as a reader? In a small group, discuss why Saramago would want to break the rules of punctuation. How does his writing style contribute to the themes he addresses?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Bloom, Harold, ed. Jose Saramago. Philadelphia: Chelsea House, 2005.

________. The Varieties of Jose Saramago. Lisbon: Fundacao Luso-Americana, 2002.

Periodicals

Bloom, Harold. ‘‘The One with the Beard Is God, the Other Is the Devil.’’ Portuguese Literary & Cultural Studies 6 (2001): 155-66.

Costa, Horacio. ‘‘Saramago’s Construction of Fictional Characters: From Terra do pecado to Baltasar and Blimunda.’’ Portuguese Literary & Cultural Studies 6 (2001): 33-48.

Daniel, Mary Lou. ‘‘Ebb and Flow: Place as Pretext in the Novels of Jose Saramago.’’ Luso-Brazilian Review, 272 (1990): 25-39.

________. ‘‘Symbolism and Synchronicity: Jose Saramago’s Jangada de Pedra’’. Hispania, 74 3 (1991): 536-41.

Frier, David. ‘‘Ascent and Consent: Hierarchy and Popular Emancipation in the Novels of Jose Saramago’’. Bulletin of Hispanic Studies, 71 1 (1994): 125-138.

________. ‘‘In the Beginning Was the Word: Text and Meaning in Two Dramas by Jose Saramago.’’ Portuguese Studies 14 (1998): 215-26.

________. ‘‘Jose Saramago’s Stone Boat: Celtic Analogues and Popular Culture.’’ Portuguese Studies 15 (1999): 194-206.

________. ‘‘Writing Wrongs, Re-Writing Meaning and Reclaiming the City in Saramago’s Blindness and All the Names.’’ Portuguese Literary & Cultural Studies 6 (2001): 97-122.

Krabbenhoft, Kenneth. ‘‘Saramago, Cognitive Estrangement, and Original Sin?’’ Portuguese Literary & Cultural Studies 6 (2001): 123-36.

Martins. ‘‘Jose Saramago’s Historical Fiction.’’ Portuguese Literary & Cultural Studies 6 (2001): 49-72.

Maurya, Vibha. ‘‘Construction of Crowd in Saramago’s Texts.’’ Coloquio/Letras 151-152 (1999): 267-278.

Sabine, Mark J. L. ‘‘Once but No Longer the Prow of Europe: National Identity and Portuguese Destiny in Jose Saramago’s The Stone Raft.’’ Portuguese Literary & Cultural Studies 6 (2001): 185-203.

Tesser, Carmen Chaves, ed. ‘‘A Tribute to Jose Saramago.’’ Hispania, 82 1 (1999): 1-28.