World Literature

Rabindranath Tagore

BORN: 1861, Calcutta, India

DIED: 1941, Calcutta, India

NATIONALITY: Indian

GENRE: Poetry, drama, fiction, nonfiction

MAJOR WORKS:

Morning Songs (1883)

The Golden Boat (1894)

Gora (1910)

Gitanjali (1912)

The Home and the World (1916)

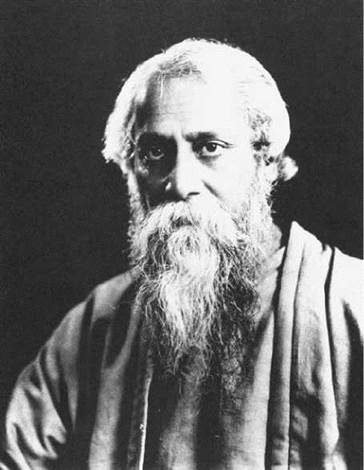

Rabindranath Tagore. Tagore, Rabindranath, photograph. Source unknown.

Overview

Rabindranath Tagore is India’s most celebrated modern author. He received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913, the first non-European to be awarded this prize. Astonishingly prolific in practically every literary genre, he achieved his greatest renown as a lyric poet. His poetry is imbued with a deeply spiritual and devotional quality, while in his novels, plays, short stories, and essays, his social and moral concerns predominate.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

Born into Literary Family in Calcutta. Tagore was born into an upper-caste Hindu family in Calcutta on May 7, 1861. His grandfather, Dwarkanath Tagore, was a key figure in what is known as the Bengal renaissance in the mid-nineteenth century. Tagore’s father, Debendranath, was a writer, religious leader, and practical businessman. Tagore was the fourteenth of his father’s fifteen children and his father’s favorite. From an early age, he embraced his father’s love of poetry, music, and mysticism, as well as his reformist outlook.

Tagore was a precocious child who showed unmistakable poetic talent. As early as eight, he was urged by his brothers and cousins to express himself in poetry. This encouragement, which continued throughout his formative years, caused his talent to flourish. when Tagore was twelve, his father took him on a four-month journey to the Punjab and the Himalayas. This was Tagore’s first contact with rural Bengal, which he later celebrated in his songs.

Public Recognition of Poetry. After publishing his first poems at the age of thirteen, Tagore’s first public recitation of his poetry came when he was fourteen at a Bengali cultural and nationalistic festival organized by his brothers. His acclaimed poem was about the greatness of India’s past and the sorrow he felt for its state under British rule. India had been controlled by Great Britain in one form or another for some years. While the British had helped India develop economically and politically and expanded local self-rule, an Indian nationalist movement was growing in the late nineteenth century. This trend continued into the first decades of the twentieth, as well.

Tagore left India at age seventeen to continue his studies in England. During this time, he read extensively in English and other European literature, forming the universalist outlook he maintained throughout his life that included: a profound desire for freedom, both personal and national; an idea of the greatness of India’s contribution to the world of the spirit; and poetry expressing both of these. His stay in England was brief, and when he returned home, he published the first of nearly sixty volumes of verse. He also wrote and acted in verse dramas and began to compose devotional songs for the Brahmo Samaj, the Hindu reformist sect his father promoted. In 1883, he married Mrinalini Devi. He was twenty-two years old, and she was ten. The couple had five children.

“The Lord of His Life’’. Tagore produced his first notable book of lyrics, Evening Songs, in 1882, followed by Morning Songs (1883). The latter work reflects Tagore’s new mood initiated by a mystical experience he had while looking at the sunrise one day. His devotion to Jivan devata (‘‘The Lord of His Life’’), a new conception of God as humanity’s intimate friend, lover, and beloved, played an important role in his subsequent work. Several poems in the volume Sharps and Flats (1886) boldly celebrate the human body, reflecting his sense of all-pervading joy in the universe.

Creative Virility. In 1890, Tagore took charge of his family’s far-flung estates, some of them in regions that are now part of Bangladesh. The daily contact with peasants and farmers aroused his empathy for the plight of India’s poor. Coming in close touch with the people and geography of Bangladesh, Tagore was inspired to write his first major collection of verse, The Golden Boat (1894). The contemplative tone of his poetry gives his work the depth and serenity of his mature voice.

In the 1880s and 1890s, Tagore’s creative output was tremendous, and his reputation steadily developed in his country as the author of poems, short stories, novels, plays, verse dramas, and essays. He moved through several phases at this time. If he began in the manner of the late Romantics, he soon became a writer of realistic fiction about everyday situations and people from all spheres of life. He frequently reinvented himself, creating new forms and introducing new genres and styles to Bengali literature—social realism, colloquial dialogue, light satire, and psychologically motivated plot development.

Music and Novels. Tagore was also known for his musical creations. His compositions started a new genre in Bengali music, known as rabindrasangit (‘‘Tagore song’’), an important part of Bengali culture. His music mingled elements of the folk music of boatmen and wandering religious with those of semiclassical love songs. He wrote more than two thousand songs in his lifetime, setting his poems, stories, and plays to music.

Tagore reached the peak of his fiction-writing career in 1910, when he published the novel Gora. This sociopolitical novel of ideas projects the author’s concept of liberal nationalism based on international brotherhood. In the West, his best-known novel is The Home and the World (1916), which frankly expresses his conflicted sentiments regarding nationalist agitation in India.

Gitanjali and Worldwide Fame. Tagore’s standing as the leading Bengali writer was confirmed in 1911, when he was given a public reception in Calcutta to celebrate his fiftieth birthday. As he was about to visit England for the third time, he fell ill, and his trip was delayed. Lacking energy to compose new writing, he began translating some of his recently published lyrics into free verse. He landed in England with a slender English manuscript of devotional poems from the volume Gitanjali (Song Offerings). In June 1912, Tagore read his translations to a select group of London literati, including W. B. Yeats and Ezra Pound. The response was overwhelming, and Tagore became a literary sensation. A limited edition of Gitanjali, with an introduction by Yeats, quickly sold out. A second edition became a best-seller.

Tagore sailed to the United States later in 1912. Pound, a tireless promoter of poetry, introduced Tagore to influential literary people in America. When Tagore returned to India in 1913, he left behind a distinguished group of European and American admirers. That year, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature—the first such recognition of an Eastern writer. The prize gratified Tagore, but the sensation it created in Bengal also alarmed him. He would never again be out of the public eye.

Tagore as Public Figure. Between 1916 and 1934, Tagore made five visits to America and traveled to nearly every country in Europe and Asia, lecturing, promoting his educational ideas, and urging international cooperation. Wherever he went, he was greeted as a living symbol of India’s cultural heritage. He was knighted by the British crown in 1915, but resigned his knighthood four years later after British troops fired into a crowd in the Punjab, killing four hundred people. He denounced the European nationalism and imperialism that had brought about the First World War. While the war was fought primarily in Europe and Africa, the Indian army was compelled to support Great Britain and provide troops for the conflict. Thousands of Indian soldiers died and were wounded during their service. In India, the call for self-rule only continued to grow.

Now a major figure in the movement for national emancipation, Tagore became close to leaders like Mohandas K. Gandhi. His relationship with Gandhi was tumultuous. He rejected Gandhi’s strategy of economic self-sufficiency and derided ‘‘the cult of the spinning wheel.’’ Instead, he favored education as the primary engine of national uplift. He founded the university called Visva-Bharati, at the site of his ashram (spiritual retreat) at Santiniketan. He also created an Institute for Rural Reconstruction, recruiting international assistance to create a model for popular education in poverty- stricken villages. Like Gandhi, Tagore fought against the Indian caste system and discrimination against the ‘‘untouchable’’ class.

In the second half of the 1930s, old age, failing health, and international turmoil put a stop to Tagore’s travels. He suffered chronic pain and long bouts of illness in his final years. As he became conscious of his approaching death, Tagore wrote some of his finest poetry, continuing to experiment with technique and addressing issues of mortality. At his death on August 7, 1941, he had achieved what the contemporary Indian American writer Pico Iyer sees as a unique position: he had become ‘‘not just the world’s leading symbol of India, but India’s leading spokesman for the world.’’

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Tagore's famous contemporaries include:

George Bernard Shaw (1856-1950): Shaw, an Irish playwright, socialist, and Nobel Prize winner, revolutionized the English stage, disposing of the Romantic conventions and devices and instituting a theater of ideas grounded in realism. His plays include Pygmalion (1912).

W. B. Yeats (1865-1939): Yeats, an Irish poet and dramatist, befriended Tagore and championed his work. Yeats's poetry included The Wanderings ofOisin (1889).

Andre Gide (1869-1951): Gide is a French author known for relentless self-exploration and credited with introducing modern experimental techniques to the French novel. His novels include The Immoralist (1902).

Thomas Mann (1875-1955): This German novelist and essayist addressed aesthetic, philosophical, and social concerns in his writing, while combining elements of literary realism and symbolism. His novels included The Magic Mountain (1924).

Mohandas K. Gandhi (1869-1948): Tagore called Gandhi "Mahatma," or ''Great Soul.'' This Indian political and spiritual leader is known for his nonviolent protests and passive resistance to British rule.

Albert Einstein (1879-1955): This German-born physicist and humanitarian was the most famous scientist of the twentieth century. His theory of relativity reconfigured notions of time, space, and matter that had been formulated by Isaac Newton.

Works in Literary Context

In terms of his literary inspiration, Tagore acknowledged three main sources: the Vaishnava poets of medieval Bengal and the Bengali folk literature; the classical Indian cultural and philosophical heritage; and European literature of the nineteenth century, particularly the English Romantic poets. Woven through all these influences is an acutely modern sensibility, in touch with the social and political currents of his era. Throughout his life, he refused to belittle Western contributions to culture, always seeking a fusion of East and West.

Innovations in Fiction. The sheer volume of Tagore’s contributions to every field of literature can obscure the innovative qualities of much of his work. For example, his two hundred short stories were the first in the Bengali language and represented a new genre in Indian prose. His stories depict the everyday lives of ordinary people, whether in rural settings or in Calcutta or in remote parts of India. The social reformer is evident in stories that target issues such as child marriage, dowries, or the tyranny of landlords.

Abundance of Poetic Themes. The Western world has viewed Tagore primarily as a poet devoted almost exclusively to spiritual themes. However, that view does not reflect the variety nor the depth of his poetic voice. Sometimes the images he used were the old religious ones of the love between man and woman as representative of the love between humanity and God. Sometimes they were the earthy images of the boatmen of the vast rivers or the country marketplace. Sometimes they were drawn from the complex life of Calcutta. They were always images that touched something deep in the hearts and memories of the Bengali people. He excelled in everything from stately love poetry to nonsense rhymes, from flights of fancy to realistic depictions of ordinary people and situations.

In his nearly sixty volumes of verse, Tagore also experimented with many poetic forms—lyrics, sonnets, odes, dramatic monologues, dialogue poems, long narrative works, and prose poems. Every volume of his poetry is distinctive, whether in form or content, and he kept developing until the end of his very long career.

One of the aspects of Tagore’s genius is his use of the Bengali language, for his musician’s ear caught natural rhythms and his free mind paid little attention to classical rules of poetry. The forms he created were new. Even in the poetry that he intended to be read rather than sung, rhythms, internal rhyme and alliteration, and a peculiar sonorousness almost make the poems sing themselves. These are things that cannot even be suggested in translation. The translations of Tagore’s poetry available in English are hardly representative of his total work. Gitanjali, on which his reputation in the West is largely based, shows nothing of the humor, for example, or intellectual rigor of which he was capable. Tagore’s published work is largely, though not completely, contained in twenty-six substantial volumes.

Influence. Tagore almost single-handedly transformed Bengali literature and enriched its culture. Bengalis continue to find in him an endless source of inspiration. His poems, plays, songs, and stories have become part of the lives of the people of the Indian subcontinent. He is not only the author of the Bangladeshi national anthem but the Indian one as well. Many leading literary figures in South America, such as Nobel Prize winners Gabriela Mistral, Pablo Neruda, and Octavio Paz, also acknowledge him as a major influence on their work.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Tagore's Gitanjali revived the tradition of mystical poetry. The following collections also explore Eastern and Western approaches to spiritual verse.

The Complete Works of Chuang Tzu (1968), nonfiction by Chuang Tzu, translated by Burton Watson. The writings attributed to the ancient Taoist hermit are among the world's funniest, and most renowned, works of scripture.

The Essential Rumi (1995), poetry by Rumi, translated by Coleman Barks. The ecstatic outbursts of the most well- known Sufi poet were written over seven hundred years ago but still resonate in today's society.

The Gift (1999), poetry by Hafiz, translated by Daniel Ledinsky. This contemporary translation of the fourteenth-century Persian poet captures his passionate celebration of life.

Songs of Innocence and Experience (1789, 1794), poetry by William Blake. A pair of magnificent illuminated manuscripts by the visionary British poet and painter that describe ''the two contrary states of the human soul.''

Mountains and Rivers without End (1996), a poem by Gary Snyder. This epic work by the ecological Buddhist of the Beat generation was forty years in the making.

Works in Critical Context

While some critics feel that Tagore’s prodigious output is uneven in its artistic value, his very prolificacy is often considered a measure of his creative achievement. Critics of Tagore’s work are nearly unanimous in designating him as one of the preeminent lyric poets of the twentieth century. While Tagore’s novels are mostly conventional in style and plotting, dealing frequently with crossed romances and improbable coincidences of fate, they are considered effective in dramatizing the moral conflicts between tradition and modernity in colonial India.

Even among more sensitive critics, Tagore’s cadences and stylistic choices appeared increasingly old-fashioned in the interwar period. Although Tagore was the first modern Indian writer to introduce psychological realism in his fiction, his novels appeared out of step with the bold innovations in the novel represented by artists such as James Joyce and Marcel Proust. The Nobel Prize made Tagore and his books instantly popular in the rest of the world. However, the Tagore craze was brief in England and the United States. On the European continent, his reputation held on somewhat longer. Both political and literary factors explain the decline in his standing. His rejection of his knighthood and criticism of British rule in India had rankled many in Britain.

However, as Tagore’s critical reputation began to decline in the English-speaking West, he was welcomed with great enthusiasm in the Middle East, the Far East, and South America. With the passing of time, more of Tagore’s writing has reached English-language readers, allowing a more complete picture of his achievements to emerge. Present-day critics worldwide are nearly unanimous in designating Tagore one of the preeminent twentieth-century authors, as well as an indispensable figure in the modern history of the Indian subcontinent.

Gitanjali. Outside his homeland, Tagore’s reputation stemmed from his presentation of the Gitanjali translation in 1912. Artistically, Gitanjali came to be seen as Tagore’s most characteristic work. Yeats, who publicly proclaimed his admiration for the poems, and Ezra Pound, who compared Tagore with Dante, set the tone for Tagore’s reception in the West. In his, introduction to the 1912 London edition, Yeats explained, ‘‘I have carried the manuscript of these translations about me for days, reading it in railway trains, or on the tops of omnibuses and in restaurants.... These lyrics display in their thought a world I have dreamed of all my life long.’’

A Times Literary Supplement reviewer agreed with Yeats, commenting, ‘‘These poems are prophetic of the poetry that might be written in England if our poets could attain the same harmony of emotion and idea.’’ Another critic noted of the poems in the collection, ‘‘Gitanjali has some of the finest descriptions of nature that Tagore has written.’’

Responses to Literature

1. Research Bengali literature and culture before the era of Tagore for a paper. How can you characterize Tagore’s specific artistic influence on Bengali society?

2. Tagore said that his plays summon up ‘‘the play of feeling, not of action.’’ What does this mean? Cite one or two of his plays to explain your answer in the form of an essay.

3. Based on The Home and the World and other works, summarize Tagore’s attitudes toward Indian anticolonial activism. Create a presentation with your findings.

4. Read several poems from Tagore’s youth, and some from his final years. In a small group, discuss some of the common elements. What do the poems tell you about the arc of his life?

5. Write an essay about the religious and spiritual perspectives expressed in Tagore’s poetry.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Agarwala, R S. Aesthetic Consciousness of Tagore. Calcutta: Abhishek Agarwal, 1996.

Atkinson, David W. Gandhi and Tagore: Visionaries of Modern India. Hong Kong: Asian Research Service, 1989.

Bhattacharya, Vivek Ranjan. Tagore’s Vision of a Global Family. New Delhi: Enkay, 1987.

Chakrabarti, Mohit. Rabindranath Tagore: A Quest. New Delhi: Gyan, 1995.

Das Gupta, Uma. Rabindranath Tagore: A Biography. Delhi and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Dutta, Krishna, and Andrew Robinson. Rabindranath Tagore: The Myriad-Minded Man. Calcutta: Rupa, 2000.

Hay, Stephen N. Asian Ideas of East and West: Tagore and His Critics in Japan, China, and India. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1970.

Khanolakara, Gangadhara Devarava. The Lute and the Plough: A Life of Rabindranath Tagore. Bombay: Book Centre, 1963.

Mukherjee, Sujit. Passage to America: The Reception of Rabindranath Tagore in the United States, 1912-1941. Calcutta: Bookland, 1964.

Naravane, Vishwanath S. Introduction to Rabindranath Tagore. Delhi: Macmillan, 1970.

Pabby, D. K., and Alpana Neogy, eds. Rabindranath Tagore’s ‘‘The Home and the World’’: New Dimensions. New Delhi: Asia Book Club, 2001.

Radhakrishnan, Sarvepalli. The Philosophy of Rabindranath Tagore. London: Macmillan, 1918.

Rhys, Ernest. Rabindranath Tagore: A Biographical Study. London: Macmillan, 1915.

Thompson, Edward J. Rabindranath Tagore: Poet and Dramatist. London: Oxford University Press, 1948.

Yeats, W. B. Introduction to ‘‘Gitanjali’’ and ‘‘Fruit-Gathering,’’ by Sir Rabindranath Tagore. New York: Macmillan, 1918.