World Literature

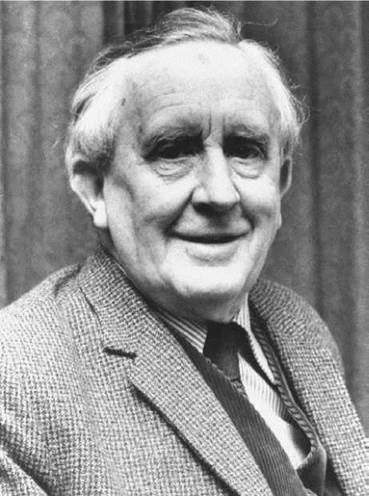

J.R.R. Tolkien

BORN: 1916, Bloemfontein, South Africa

DIED: 1995, Thirsk, England

NATIONALITY: English

GENRE: Fiction, nonfiction

MAJOR WORKS:

The Hobbit, or There and Back Again (1936)

The Lord of the Rings (1954-1955)

The Silmarillion (1977)

J.R.R. Tolkien. Tolkien, J.R.R., photograph. AP Images.

Overview

A leading linguist of his day, Tolkien was an Oxford University professor who, along with colleagues C. S. Lewis and Charles Williams, helped revive popular interest in the medieval romance and the fantastic tale genre. Tolkien is best known for his novels of epic fantasy, the trilogy The Lord of the Rings (1954-1955). Beneath his charming, adventurous surface story of Middle Earth lies a sense of quiet anguish for a vanishing past and a precarious future. His continuing popularity evidences his ability to draw audiences into a fantasy world, at the same time drawing attention to the oppressive realities of modern life. Many critics claim that the success of Tolkien’s trilogy has made possible the contemporary revival of ‘‘sword and sorcery’’ literature.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

Orphaned Young, Educated at Oxford. John Ronald Reuel Tolkien was born the son of English-born parents in Bloemfontein, in the Orange Free State of South Africa, where his father worked as a bank manager. To escape the heat and dust of southern Africa and to better guard the delicate health of her sons, Tolkien’s mother moved back to England with him and his brother when they were very young. Within a year of this move, their father, Arthur Tolkien, died in Bloemfontein; a few years later, the boys’ mother died as well. The boys lodged at several homes from 1905 until 1911, when Tolkien entered Exeter College, Oxford.

Tolkien married his longtime sweetheart, Edith Bratt, and served for a short time with the Lancashire Fusiliers, a British infantry regiment assigned to the Western front during World War I. World War I was a horrific conflict that cost millions of military and civilian lives across Europe: England alone suffered nearly 900,000 military deaths and about twice that many casualties. While in England recovering from an illness he developed on the front in 1917, Tolkien began writing ‘‘The Book of Lost Tales,’’ which eventually became The Silmarillion (1977) and laid the groundwork for his stories about Middle Earth. After the end of the war, Tolkien returned to Oxford, where he joined the staff of the Oxford English Dictionary and began work as a freelance tutor.

The Coalbiters and the Inklings. In 1920 Tolkien was appointed Reader in English Language at Leeds University, where he collaborated with E. V. Gordon on an acclaimed translation of ‘‘Sir Gawain and the Green Knight,’’ which was completed and published in 1925. (Some years later, Tolkien completed a second translation of this poem, which was published posthumously.) The following year, having returned to Oxford as Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon, Tolkien became friends with a coworker, C. S. Lewis, author of The Chronicles of Narnia (1950-1956). They shared an intense enthusiasm for the myths, sagas, and languages of northern Europe; and to better enhance those interests, both attended meetings of ‘‘The Coalbiters,” an Oxford club founded by Tolkien where Icelandic sagas were read aloud. The influence of these and other Germanic tales can be seen clearly in Tolkien’s fantasy fiction.

As a writer of imaginative literature, Tolkien is best known for The Hobbit (1936) and The Lord of the Rings, tales that were conceived during his years attending meetings of ‘‘The Inklings,’’ an informal gathering of like- minded friends, initiated after the demise of The Coalbiters. The Inklings, which was formed during the late 1930s and lasted until the late 1940s, was a weekly meeting held in Lewis’s sitting-room at Magdalen. At these meetings, works-in-progress were read aloud, discussed, and critiqued by the attendees, all interspersed with free-flowing conversation about literature and other topics. The nucleus of the group consisted of Tolkien, Lewis, and Lewis’s friend, novelist Charles Williams, bound together by their belief in Christianity and their love of stories. Having heard Tolkien’s first hobbit story read aloud at a meeting of the Inklings, Lewis urged Tolkien to publish The Hobbit, which appeared in 1937. Tolkien also read a major portion of The Fellowship of the Ring (1954) to the Inklings group before it disbanded in the late 1940s.

The Father of Fantasy. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings appeared in three volumes in England in 1954 and 1955, and soon thereafter in the United States. The books made him a cult figure in the United States, especially among high school and college students. Uncomfortable with this status, he and his wife lived quietly in Bournemouth for several years, until Edith’s death in 1971. In the remaining two years of his life, Tolkien returned to Oxford, where he was made an honorary fellow of Merton College and awarded a doctorate of letters. He was at the height of his fame as a scholarly and imaginative writer when he died in 1973. Critical study of his fiction continues and has increased in the years since his death.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Tolkien's famous contemporaries include:

Aldous Huxley (1894-1963): Huxley was an English poet, essayist, and novelist whose most popular work is Brave New World (1932).

Norman Rockwell (1894-1978): The work of this American artist and illustrator frequently featured on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post.

Winston Churchill (1874-1965): Churchill, who held the position of prime minister of the United Kingdom during World War II, was also a renowned author.

Virginia Woolf (1882-1941): This English novelist used ''free indirect discourse,'' a style of writing in which an author attempts to describe the many avenues a person's thoughts follow, a deceptively difficult feat in literature.

Louis Armstrong (1901-1971): This American jazz musician's unique, strained vocals made ''What a Wonderful World'' a hit.

Works in Literary Context

The concise edition of the Oxford English Dictionary defines philology as ‘‘the study of literature in a wide sense, including grammar, literary criticism and interpretation, the relation of literature and written records to history, etc.’’ The stories of Middle Earth made a quiet, unassuming teacher of linguistics—whose life in most ways was uneventful and modest—into an international celebrity. Tolkien wrote in the foreword to the Ballantine edition of The Lord of the Rings trilogy that his task in writing his fairy-stories is ‘‘primarily linguistic in inspiration.’’

Philology. Tolkien was a philologist in the literal sense of the word: a lover of language. In his scholarly biography The Inklings, Humphrey Carpenter explained, ‘‘It was a deep love for the look and sound of words [that motivated Tolkien], springing from the days when his mother had given him his first Latin lesson.’’ After learning Latin and Greek, Tolkien taught himself some Welsh, Old and Middle English, Old Norse, and Gothic, a language with no modern descendant—he wrote the only poem known to exist in that tongue. Later, he added Finnish to his list of languages; the Finnish epic The Kalevala had a great impact on his Silmarillion. The Finnish language itself, said Carpenter, formed the basis for ‘‘Quenya,’’ the High-elven tongue of his stories.

Ancient Myths. So much of the art of Tolkien’s storytelling relies on ancient, archetypal patterns derived from Greek, Germanic, Celtic, and Old and Middle English models. Tolkien’s expertise in these established forms reveals a passion he developed early in life for exploring lost cultures and the ancient roots of modern cultures. Though the mythologies of many cultures can be discerned in The Lord of the Rings, the Germanic and Norse sagas are particularly dominant.

Allegory of the Modern World? Because The Lord of the Rings was written during World War II, it has been analyzed as a fictionalized, allegorical account of those horrors—Sauron, for example, being the equivalent of Hitler, and so forth. Nonetheless, Tolkien explicitly rejected such an interpretation. In the foreword to the Ballantine edition of The Lord of the Rings, he stated, ‘‘As for any inner meaning or ‘message,’ it has in the intention of the author none. It is neither allegorical nor topical.’’ He continued, ‘‘I cordially dislike allegory in all its manifestations, and have always done so since I grew old and wary enough to detect its presence. I much prefer history, true or feigned, with its varied applicability to the thought and experience of readers. I think that many confuse ‘applicability’ with ‘allegory’ but the one resides in the freedom of the reader, and the other in the purposed dominations of the author.’’

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

The story of David and Goliath is perhaps the most popular story of an underdog, but Frodo's struggle against the dark forces of Middle Earth, to some, is an equally compelling tale of a surprise victor. As the popularity of each of these stories indicates, humans enjoy participating in the fight against seemingly superior powers. Here are some more popular underdog stories:

The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1831), a novel by Victor Hugo. Hugo's unlikely hero is Quasimodo, a hunchback who lives in Paris's famous cathedral.

Rocky (1976), a film directed by John Avildsen. This Academy Award winner is the story of an obscure boxer in Philadelphia who gets a shot at the world championship.

Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone (2001), a novel by J.K. Rowling. Harry, an orphan raised by his cruel aunt and uncle, is transformed from a timid weakling to a powerful hero when he attends Hogwarts, a school for wizards.

Works in Critical Context

Critical response to Tolkien immediately after the publication of his most well-known work, The Lord of the Rings, was divided. Many critics felt the trilogy was written for children and consequently was not worthy of the same kind of critical evaluation as other, more ‘‘adult’’ fiction.

Upon its release, many critics, were hostile toward The Lord of the Rings because the book did not fit current fashions of adult fiction. It was not a realistic contemporary novel, and in the words of Edmund Wilson, ‘‘It is essentially a children’s book—a children’s book which has somehow got out of hand.’’ Such misunderstandings were anticipated by the three authors commissioned to write the jacket blurb, so they concentrated on comparable authors such as Thomas Malory and Ariosto and on genres such as science fiction and heroic romance.

What these early critics could not predict, however, was that The Lord of the Rings would reawaken an appetite for fantasy literature among readers and create a new genre: adult fantasy. Since its publication, those critics who appreciate Tolkien have worked to establish criteria by which Tolkien and other fantasists should be judged. Among them was Elizabeth Cook, who wrote in The Ordinary and the Fabulous, ‘‘The inherent greatness of myth and fairy tale is a poetic greatness. Childhood reading of symbolic and fantastic tales contributes something irreplaceable to any later experience of literature. ... The whole world of epic, romance, and allegory is open to a reader who has always taken fantasy for granted, and the way into it may be hard for one who never heard fairy tales as a child.’’

Legacy. Tolkien’s life’s work, the creation of Middle Earth, ‘‘encompasses a reality that rivals Western man’s own attempt at recording the composite, knowable history of his species,’’ wrote Augustus M. Kolich in the Dictionary of Literary Biography. Kolich continued, ‘‘Not since Milton has any Englishman worked so successfully at creating a secondary world, derived from the real world, yet complete in its own terms with encyclopedic mythology; an imagined world that includes a vast gallery of strange beings: hobbits, elves, dwarfs, orcs, and, finally, the men of Westernesse.’’ Throughout the years, Tolkien’s works—especially The Lord of the Rings—have pleased countless readers and fascinated critics who recognize their literary depth.

Responses to Literature

1. Discuss the effect of using children and other characters small in stature as opponents of evil in The Hobbit. Once you have explored this topic, use your conclusions to write a short children’s story featuring a young character fighting the forces of evil.

2. Tolkien claimed that The Lord of the Rings is not meant to be an allegory of the modern world, specifically World War II. After doing some research on World War II, write a short paper tracing similarities and differences between the vast struggle faced by Middle Earth and that faced by our world during World War II.

3. Using the Internet and the library, research ‘‘flat characters’’ and ‘‘round characters.’’ Then, choose four characters from either The Hobbit or The Lord of the Rings. Based on your research, do you feel these characters are flat characters or round characters? Compare them to characters from at least one other novel and one film who are flat or round characters. How could the flat characters be made round? Support your argument in a brief essay.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Carpenter, Humphrey. The Inklings: C. S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, Charles Williams and their Friends. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1979.

Collins, David R. J.R.R. Tolkien: Master of Fantasy. Minneapolis, Minn.: Lerner, 1992.

Cook, Elizabeth. The Ordinary and the Fabulous. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969.

Helms, Randel. Tolkien and the Silmarils. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981.

Johnson, Judith A. J.R.R. Tolkien: Six Decades of Criticism. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1986.

Ready, William. Understanding Tolkien and The Lord of the Rings. New York: Warner Paperbacks, 1969.

Shippey, T. A. The Road to Middle-earth. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1983.