World Literature

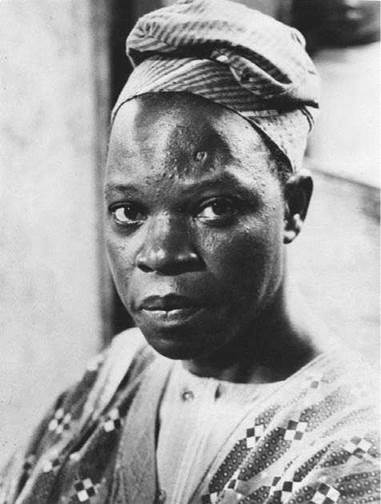

Amos Tutuola

BORN: 1920, Abeokuta, Nigeria

DIED: 1997, Ibadan, Nigeria

NATIONALITY: Nigerian

GENRE: Fiction

MAJOR WORKS:

The Palm-Wine Drinkard and His Dead Palm-Wine Tapster in the Deads’ Town (1952)

My Life in the Bush of Ghosts (1954)

Yoruba Folktales (1986)

Amos Tutuola. Tutuola, Amos, photograph. Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, The University of Texas at Austin. Reproduced by permission.

Overview

Amos Tutuola was the first Nigerian writer to achieve international recognition. He spun adventure fantasies based on traditional Yoruba folktales, writing in an idiosyncratic, deliberately flawed pidgin English. His works are crudely constructed and restricted in narrative range, yet are highly imaginative. Tutuola is one of the most successful stylists in twentieth-century African literature.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

Writing on the Job. Tutuola was born in the western Nigerian town of Abeokuta in 1920, when Nigeria was ruled by the British as a part of the British Empire. Tutuola completed six years in missionary schools. When his father, a cacao farmer, died in 1939, he left school to learn a trade. Tutuola worked as a coppersmith in the Royal Air Force during World War II, but he lost his position in postwar demobilization. (In the postwar period, Nigeria demanded self-government from the British, resulting in a series of short-lived constitutions through the early 1950s.) He found employment as a messenger for the Department ofLabor in Lagos. The job left him ample free time, and he took to writing English versions of stories he had heard old people tell in Yoruba.

In the late 1940s, he wrote to Focal Press, an English publisher, asking if they would consider a manuscript about spirits in the Nigerian bush. Several months later, The Wild Hunter in the Bush of Ghosts arrived, wrapped in brown paper and bound with twine. The mythological adventure story, clearly the work of a novice, would not be published until 1982. Had it been published earlier, it would not have generated the same excitement among readers overseas as did Tutuola’s next narrative, a bizarre yarn with the improbable title The Palm-Wine Drinkard and His Dead Palm-Wine Tapster in the Deads’ Town (1952).

The Palm-Wine Drinkard is a voyage of the imagination into a never-never land of magic and marvels. The prodigious drinker of palm wine appears at first to be an unpromising hero, but he cleverly circumvents numerous monsters and misadventures and settles the cosmic dispute between Heaven and Land, ending a catastrophic drought.

A Colonial Throwback? Tutuola was lucky to get this second story published and luckier still that it gained commercial success. The book might have sunk into obscurity had it not been enthusiastically reviewed by well-known poet Dylan Thomas. Within a year, an American edition won similar acclaim. It was eventually translated into fifteen languages.

In Nigeria, however, Tutuola’s writing received an unfriendly reception. Educated Nigerians were shocked that a book written in substandard English by a lowly Lagos messenger was being lionized abroad. Tutuola’s first books appeared at the close of the colonial era, when Africans were trying to prove to the outside world that they were ready to manage their own political affairs. For educated Africans, acutely conscious of their image abroad, the naive fantasies of Tutuola projected a primitive impression.

Despite the criticism from his countrymen, Tutuola pressed on, producing more adventure stories cut from the same cloth. My Life in the Bush of Ghosts (1954), opens as its hero, a boy of seven, abandoned by his stepmothers, is left to wander in the bush during a tribal war. He spends twenty-four years wandering in an African spirit world, until a ‘‘television-handed goddess’’ helps the young man escape. Simbi and the Satyr of the Dark Jungle (1955), in which a pampered only child defies her parents and undertakes a solitary journey, displays for the first time signs of formal literary influence. It is Tutuola’s first book to be divided into numbered chapters, and it is written from the third-person point of view. Tutuola was becoming conscious of himself as an author and reading more widely. He continued to work as a messenger, writing in his spare time.

Imagination and Grotesque Fantasy. As Tutuola continued his work as both a writer and a messenger, Nigeria was continuing to undergo political change. In the mid- to late 1950s, the country moved further into self-government and became a fully independent member of the British Commonwealth in 1960. In 1963, Nigeria became a republic, with Nnamdi Azikiwe serving as its first president. Internal unrest soon became a hallmark of Nigeria, with two military coups taking place in 1966 alone.

While Nigeria was going through these changes, Tutuola published such works as Feather Woman of the Jungle (1962). This book is Tutuola’s most stylized work. The narrative frame is structured somewhat like the Arabian Nights, an elderly chief entertains villagers for ten nights with accounts of his past adventures. As with Tutuola’s other works, the technique recalls devices from oral storytelling. Tutuola published nothing between Ajaiyi and His Inherited Poverty (1967) and The Witch-Herbalist of the Remote Town (1981), but the hiatus had no discernible impact on his chosen methods. In The Witch-Herbalist, a hunter goes on a quest to find a cure for his wife’s barrenness. He survives bizarre and sometimes frightening encounters over six years, eventually reaching the Remote Town. He gets the medicine from the herbalist, sips some on his return to stave off hunger, and gives the rest to his wife, who promptly becomes pregnant. However, so does he, and he must undergo further trials and torments before being cured.

Evolved Late Works. Yoruba Folktales (1986) is Tutuola’s first effort at preserving, rather than retelling, the stories that are the communal literary property of his people. Tutuola remains faithful to tradition but occasionally adds some zaniness to spice up characterization and plot. The grammatical blunders and stylistic inventions found in Tutuola’s earlier works are absent from Yoruba Folktales. The reason is not mysterious: The book was targeted at primary school classrooms, and one cannot address Nigerian schoolchildren in a fractured foreign tongue.

Tutuola’s final publication, The Village Witch Doctor, and Other Stories (1990), contains eighteen stories based on traditional Yoruba fables. Like most of Tutuola’s previous work, the stories deal with greed, betrayal, and tricksterism. After more than forty years, the same buoyant imagination and fascination with comically grotesque fantasy worlds were evident.

Tutuola resided in Ibadan and Ago-Odo, Nigeria, for most of his life. For several years, he worked for the Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation. He also traveled around Africa, Europe, and the United States, serving stints as a visiting fellow at the University of Ife, Nigeria (1979), and the University of Iowa (1983). He died in Ibadan in June 1997 from hypertension and diabetes.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Tutuola's famous contemporaries include:

Chinua Achebe (1930-): Nigerian novelist and essayist whose novel Things Fall Apart (1958) is the most widely read work of African literature.

Wole Soyinka (1934-): This Nigerian playwright, poet, and essayist was also a Nobel Prize winner. His plays include A Dance of the Forest (1960).

Fela Anikulapo-Kuti (1938-1997): This Nigerian musician and political activist sang in cunningly broken English. His albums include Zombie (1976).

Cheikh Anta Diop (1923-1986): This Senegalese anthropologist and historian studied ancient Africa and the origins of humanity. His books include The African Origin of Civilization: Myth or Reality? (1974).

James Baldwin (1924-1987): This African American novelist and essayist wrote Go Tell It on the Mountain (1953).

Gabriel Garcia Marquez (1927-): This Colombian novelist wrote the Latin American epic One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967).

Italo Calvino (1923-1985): This Italian author of short stories and novels wrote modern fables, such as the Our Ancestors trilogy (1952-1959).

Works in Literary Context

When The Palm-Wine Drinkard gained public attention abroad, some Nigerians were contemptuous of Tutuola’s efforts because he had borrowed heavily from the well- known Yoruba novelist D. O. Fagunwa. Some Yoruba readers accused him of plagiarism. Indeed, the narrative devices, and much of the content of Tutuola’s early writings, echo the work of Fagunwa rather precisely. Tutuola admitted as much in interviews and letters and never pretended that his stories were original creations. Rather, he was following in the norm of indigenous oral tradition. In oral art, what matters most is not uniqueness of invention but the adroitness of performance. A storyteller’s contribution is to tell old, well-known tales in an entertaining manner. Thus, he was creatively exploiting, not pilfering, his cultural heritage.

Fagunwa was not Tutuola’s only teacher. He had also read John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress (1678) and the Arabian Nights (c. 800-900), both classic adventure stories fabricated out of a chain of old tales loosely linked together. Events in Bunyan’s narrative, such as Christian’s visits to Vanity Fair, Doubting Castle, and the Celestial City, may have served as models for some of Tutuola’s romantic adventures. However, unlike Pilgrim’s Progress—and Fagunwa’s novels—Tutuola’s narratives are not religious allegories. It is Yoruba oral tradition, not the Christian Bible, that influences Tutuola’s works. Tutuola may have learned from Bunyan how to put an extended quest tale together, but in substance and spirit he was a thoroughly African storyteller.

The Heroic Quest. Tutuola’s storytelling method did not change much over the years. His stories typically concern a naive or morally weak character who is inspired or forced to embark on a spiritual journey. He or she encounters danger, confronts a tremendous variety of shape- shifting spirits from the underworld, and displays the heroic traits of the most popular folktale protagonists: hunter, magician, trickster, superman. Tutuola varies the quest pattern slightly from book to book, but never abandons it entirely. Because of their spiritual themes, allegorical characters, and symbolic plots, Tutuola’s works have been called mythologies or epics rather than novels.

Ancestral, Yet Contemporary. Tutuola employs many techniques associated with oral traditions in his novels and stories. The supernatural, fantastical, and grotesque are commonplace in Yoruba folklore. However, he embellishes ancestral tales with modern and Western elements, such as the ‘‘television-handed goddess’’ in The Palm-Wine Drinkard, which, in context, appear both exotic and in keeping with contemporary Nigerian changing culture. The result is a collage of borrowed materials put together in an eclectic manner by a resourceful raconteur working well within oral conventions.

Use of Language. Perhaps the most unique aspect of Tutuola’s novels is his unconventional use of the English language: skewed syntax, sometimes broken English, and idiosyncratic diction. For example, Tutuola wrote in The Palm-Wine Drinkard: ‘‘[If] I were a lady, no doubt I would follow him to wherever he would go, and still as I was a man, I would jealous him more than that.’’ His usage of ‘‘jealous’’ as a verb reflects Yoruban grammatical constructs, in which adjectives and verbs are often interchangeable. Tutuola coins new words, incorporates Nigerian idiom and patois, and even spells with startling and charming inventiveness. In a unique way, he resolves the dilemma of the African writer representing his heritage authentically while working in the language of the colonizer.

Influence. Most critics agree that Tutuola’s literary style and method are highly personal and have had little influence on subsequent writers in Nigeria. However, his contribution—refashioning traditional Yoruba myths and folktales and fusing them with modern life—is increasingly appreciated. Tutuola retains a wide international readership, and his works are commonly read in Nigerian schools. Students of African literature in Europe and the United States were also influenced by Tutuola and his writings.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

The novels of Amos Tutuola represent a modern effort to preserve and revive folklore traditions. The following works of modern literature also invoke, update, or invent folktales:

The Robber Bride (1993), a novel by Margaret Atwood. This novel is loosely based on a fairy tale in the Grimm Brothers' collection, peppered with allusions to fairy tales and folklore.

Ceremony (1977), a novel by Leslie Marmon Silko. In this contemporary novel, a Native American returning from World War II delves into the ancient stories of his people to overcome despair.

Mules and Men (1935), a travelogue by Zora Neale Hurston. This unique anthropological travelogue documents the hoodoo practices of southern blacks, with many folktales thrown in.

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), a children's novel by L. Frank Baum. This celebrated fantasy book for children, the first of a long series, is a conscious attempt to create a modern American fairy tale, or ''wonder tale.''

The Jungle Book (1894), a story collection by Rudyard Kipling. This book of fables uses animals in an anthropomorphic manner to give moral lessons.

Works in Critical Context

Audiences were sharply divided over Tutuola’s work when it first began to appear in the 1950s. At first, Anglo-American commentators praised the style and content of Tutuola’s fiction for its originality and imagination. Tutuola’s later offerings were not as enthusiastically received in England and America as his first two. As new African voices reached the Western public, reviewers complained that Tutuola’s writing seemed repetitive and rudimentary. His novelty had worn off, and the pendulum of critical opinion had begun to reverse direction. Later it would return to a more neutral position.

Early Nigerian critics expressed doubt about Tutuola’s writing ability, but have since reclaimed him as a unique and innovative storyteller. In Nigeria, the pendulum started to swing in a more positive direction shortly after the nation achieved independence in 1960. The consensus of opinion today is that he is far too important a phenomenon to be overlooked.

The Palm-Wine Drinkard. The appearance of The Palm-Wine Drinkard was greeted with hostility by Nigerian intellectuals. Some maintained that Tutuola’s work was an unprincipled act of piracy, especially since he was writing in English for a foreign audience rather than in Yoruba for his own people, and that his obvious lack of proficiency in English would give readers overseas a poor opinion of Africans, thereby reinforcing their prejudices.

However, European and American readers found Tutuola an exotic delight. Dylan Thomas called the novel ‘‘bewitching.’’ British critic V. S. Pritchett wrote in the New Statesman and Nation that “Tutuola’s voice is like the beginning of man on earth.’’ Perhaps Tutuola’s Nigerian critics were right after all. To native speakers of English, his splintered style was an amusing novelty; to educated Nigerians who had spent years polishing their English, it was an abomination.

Responses to Literature

1. In a paper, identify some of the particular patterns of error or peculiarity in how Tutuola renders the English language. Assuming that these aberrations are purposeful, what purposes do they serve? Are they effective, and do they achieve what they are intended to?

2. Tutuola incorporates the phenomena of modern life into the fantasy worlds of his stories, yet he also seems to mourn the loss of ancient African traditions. How would you describe his attitude toward African modernity? Put your answer in the form of an essay.

3. What challenges did Tutuola confront in transmitting oral traditions into print? Would you think that these are challenges common to any writer facing this same task within any culture, or is this exclusive to Tutuola’s culture? Create a presentation with your findings.

4. As Nigeria struggled to overthrow colonialism, many of Tutuola’s countrymen condemned him for disseminating a poor image of his people. Do you agree? Was his work a worthy representation of Nigerian culture? Write an essay that addresses these questions.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Asein, Samuel O., and Albert O. Ashaolu, eds. Studies in the African Novel. Ibadan, Nigeria: Ibadan University Press, 1986.

Collins, Harold R. Amos Tutuola. New York: Twayne, 1969.

Herskovits, Melville J., and Frances S. Herskovits. Dahomean Narrative: A Cross-Cultural Analysis. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 1958.

King, Bruce, ed. Introduction to Nigerian Literature. Ibadan, Nigeria: Evans Brothers, 1971.

Lindfors, Bernth, ed. Critical Perspectives on Amos Tutuola. Washington, D.C.: Three Continents, 1975.

Periodicals

Coates, John. ‘‘The Inward Journey of a Palm-Wine Drinkard.’’ African Literature Today 11 (1980): 122-29.

Ferris, William R., Jr. ‘‘Folklore and the African Novelist: Achebe and Tutuola.’’ Journal ofAmerican Folklore 86 (1973): 25-36.

Irele, Abiola. ‘‘Tradition and the Yoruba Writer: D. O. Fagunwa, Amos Tutuola and Wole Soyinka.’’ Odu 11 (1975): 75-100.

Nkosi, Lewis. ‘‘Conversation with Amos Tutuola.’’ Africa Report 9, no. 7 (1964): 11.

Obiechina, Emmanuel. ‘‘Amos Tutuola and the Oral Tradition.’’ Presence Africaine 65 (1968): 85-106.