World Literature

Mario Vargas Llosa

BORN: 1936, Arequipa, Peru

NATIONALITY: Peruvian

GENRE: Fiction, nonfiction

MAJOR WORKS:

The Time of the Hero (1963)

The Green House (1966)

Conversation in the Cathedral (1969)

Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter (1977)

The War of the End of the World (1981)

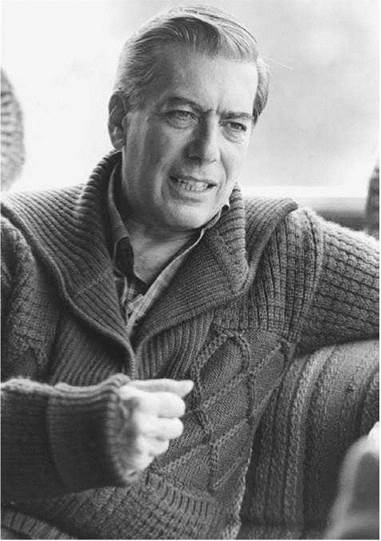

Mario Vargas Llosa. Vargas Llosa, (Jorge) Mario (Pedro), photograph. AP Images.

Overview

Few writers from South America have achieved the literary status and international recognition of Mario Vargas Llosa. A major figure in contemporary literature, Vargas Llosa is respected for his insightful examination of social and cultural themes and for the structural craftsmanship of his work. Vargas Llosa is best known for his novels, in which he combines realism with experimentation to reveal the complexities of human life and society. Never afraid of intellectual controversy, he has always been outspoken on Latin American cultural and political issues. He ran for the presidency of Peru in 1990, narrowly losing to Alberto Fujimori. in spite of his involvement in politics, literature remained his first passion, and it is in the art of storytelling that his talent has shone the most.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

Brutal Discipline Shaped into Fiction. Jorge Mario Pedro Vargas Llosa was born into a middle-class family on March 28, 1936, in Arequipa, Peru’s second largest city. For the first ten years of his life he lived in Cochabamba, Bolivia, with his mother and grandparents. He returned to Peru in 1946 when his parents, who had divorced shortly before his birth, were reunited. Ernesto Vargas, disdainful of what he perceived as his son’s unmanly personality, shipped the teenager off to the Leoncio Prado military academy. This experience marked the future writer’s life; it was his first encounter with the institutional violence that affected the various social groups in Peru’s ethnically diverse society. Vargas Llosa spent two years at the Leoncio Prado, then returned to his mother’s suburban home to finish high school. Vargas Llosa worked for a local newspaper during that time and wrote a play, which was staged but never published.

In 1953, Vargas Llosa studied literature and law at the University of San Marcos in Lima. During these years, Peru was governed by the military dictator General Manuel Odrla, who had overthrown the nation’s democratic government in 1948. San Marcos was a stronghold for clandestine opposition to Odria’s dictatorship. This proved crucial in Vargas Llosa’s intellectual formation as he joined a student cell of the Peruvian Communist Party.

In 1959, Vargas Llosa left Peru to pursue doctoral studies at the Universidad Complutense of Madrid, Spain. His collection of short stories, Los jefes (The Cubs and Other Stories) (1959) was awarded the Leopoldo Alas Prize in Spain and published that year in Barcelona. Vargas Llosa later moved to Paris, where he worked as a journalist, taught Spanish, and continued to write. He became acquainted with several Latin American writers also living in Paris, including Julio Cortazar from Argentina and Carlos Fuentes from Mexico. In the 1960s, all three would be leaders of a literary ‘‘boom’’ that brought Latin American literature to international attention.

Vargas Llosa’s painful experiences at Leoncio Prado were the basis for his first novel, The Time of the Hero (the title changed from the Spanish-language version La ciudad y losperros, meaning ‘‘the city and the dogs’’) (1963). The work gained instant notoriety when Peruvian military leaders condemned it and publicly burned one thousand copies.

Experiments in Social Narrative. The Green House (La Casa Verde) (1966), Vargas Llosa’s next novel, also won wide acclaim and established him as an important young writer. He followed up his success with Conversation in the Cathedral (Conversacion en la catedral) (1969), a monumental narrative exploring the moral depravity of Peruvian life under dictator Manuel Odria. In 1973, Vargas Llosa published his first satirical novel, Captain Pantoja and the Special Service (Pantaleon y las visitadoras). With biting wit, the novel demonstrates Vargas Llosa’s disdain for military bureaucracy.

Fact and Fiction. Four years later, Vargas Llosa published his autobiographical and most internationally popular novel, Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter (La tia Julia y el escribidor) (1977). While this book is less complicated structurally than his earlier novels, Vargas Llosa’s manipulation of point of view is of primary importance. Half the chapters in the book represent a fictionalized version of the author’s short first marriage to his Aunt Julia. The alternate chapters are soap opera scripts composed by a radio scriptwriter, Pedro Camacho, whose stories of infanticide, incest, prostitution, religious fanaticism, and genocide keep his audience glued to the radio. Vargas Llosa stretches the limits of fact and fiction by using not only the historical real names of his main characters, but many historical events and characters from Peruvian public life as well.

Vargas Llosa produced an epic historical novel based on a true story, The War of the End of the World (Laguerra del fin del mundo), in 1981. The plot concerns a rebellion in the Brazilian backlands late in the nineteenth century, reflecting the plight ofthe poor throughout Latin American history. It received international acclaim and is considered by some to be Vargas Llosa’s masterpiece.

Its huge success was only the beginning of an intense decade for Vargas Llosa, both as a writer and an influential public figure in Peru. In the 1980s he published a major anthology of his journalistic essays, Against All Odds (Contra viento y marea) (1983-1990). Its three volumes portray the shift in his political perspective, from his early admiration for socialism in the 1960s to his defense of free-market capitalism in the 1980s. This shift to a conservative position often placed him at the center of controversy both in Peru and abroad. After twelve years of progressive military rule, civilian rule was restoredin 1980. Vargas Llosa maintained such close political ties to President Fernando Belaunde Terry that he was offered the post ofprime minister, which he did not accept.

The Storyteller and the Candidate. Vargas Llosa’s political stands are present in his next novel, The Real Life of Alejandro Mayta (Historia de Mayta) (1985). Using real and imagined events, it tells the story of Alejandro Mayta, a Marxist revolutionary who organized a failed rebellion against the Peruvian government in the late 1950s and quickly faded from public view. At the same time, a contemporary novelist in the 1980s (like Vargas Llosa himself) is trying to track down information about the legendary Mayta, sometimes embellishing factual material with fiction to enhance the significance of his story. The novel is a politically charged inquiry into the relationship between representation and reality, fact and depiction.

In his 1987 work The Storyteller (El hablador), Vargas Llosa once again explores stories told from multiple points of view. The Storyteller concerns a Native American tribe, the Machiguengas, and in particular the community’s storyteller, Saul Zuratas. The book energetically questions the multifaceted identity of Peruvian society, in which primitive and modern lifestyles are forced to coexist in conflict and contradiction. Peru has the largest Native American population in the western hemisphere: about half its population of 28 million is Native American. More than 15 percent of Peruvians speak Quechua, an indigenous Peruvian language, and Native American storytelling traditions have had a marked effect on modern Peruvian literature.

Vargas Llosa believes that a Latin American writer is obligated to speak out on political matters. This belief led Vargas Llosa in 1987 to speak out against the reformist tendencies of Peruvian President Alan Garcia. His protest quickly led to a mass movement against nationalization of Peru’s banking industry, and the government was forced to back down. Vargas Llosa’s supporters went on to create Fredemo, a conservative political party calling for democracy, a free market, and individual liberty. The novelist ran for the presidency of Peru in 1990 and, despite being heavily favored, lost in a second-round vote to the then unknown Alberto Fujimori.

Later Career. Shortly before campaigning for the presidency, Mario Vargas Llosa published an erotic novel, In Praise of the Stepmother (Elogio de la madrastra; 1988), and followed it up with a work of literary criticism, Lies That Tell the Truth (or A Writer’s Reality, 1991). He offers a critical look into his campaign in his 1993 memoir, A Fish in the Water (Elpez en el agua: Memorias).

Since his political defeat, Vargas Llosa has lived in Europe and concentrated on his first love, literature. His novel Death in the Andes (Lituma en los Andes; 1993) was awarded Spain’s prestigious Planeta Prize. His 1997 novel The Notebooks of Don Rigoberto (Los cuadernos de don Rigoberto) marked the first time any publisher had released a title in all Spanish-language markets on the same day. His most recent works of fiction are The Way to Paradise (El paraiso en la otra esquina; 2003) and The Bad Girl (Travesuras de la nina mala; 2006).

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Vargas Llosa's famous contemporaries include:

Gabriel Garcia Marquez (1927—): Colombian novelist, author of One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Fidel Castro (1926—): Cuban revolutionary and government leader from 1959 to 2008.

V. S. Naipaul (1932—): British novelist and essayist born in Trinidad and of Indian descent.

Vaclav Havel (1936—): Czech playwright, essayist, and president of Czechoslovakia (1989-1992) and the Czech Republic (1993-2003).

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Mario Vargas Llosa strove to write the ''total novel,'' a sweeping view of society within the pages of a single work. Here are some other notable works that fit that definition:

The Sound and the Fury (1929), a novel by William Faulkner. The lives of the Compson family, expressed in stream-of-consciousness narrative, represent in microcosm the declining culture of the American South.

Madame Bovary (1857), a novel by Gustave Flaubert. In this novel that is credited as a founding text of literary realism, Flaubert uses the failing marriage of Emma and Charles Bovary to depict French bourgeois culture of the period.

Sister Carrie (1900), a novel by Theodore Dreiser. In this panorama of America at the turn of the century, a young country girl ascends in social class as mistress to a bar manager, finally becoming a well-known stage actress.

The Rules of the Game (1939), a film written and directed by Jean Renoir. This comedy of manners concerns a group of French aristocrats and the servants they employ.

Works in Literary Context

As a teenager in the coastal town of Piura, Mario Vargas Llosa developed his affinity for literature, greatly admiring the works of a variety of authors, including Alexander Dumas and Fyodor Dostoyevsky. At the university, he was attracted by the rich narrative technique in the novels of William Faulkner, whose work he admired greatly.

The Total Novel. Vargas Llosa’s discovery of Faulkner was crucial in the experimental nature of many of his novels and his concept of the ‘‘total novel,’’ an attempt to depict through writing as many facets of reality as possible. Another important source for Vargas Llosa’s theory of the total novel is Gustave Flaubert, author of Madame Bovary (1857). For Vargas Llosa, Flaubert’s writing is key to understanding realism and the modern novel. If the novel is a genre that captures all aspects of reality, the novelist should strive to represent all aspects of life with equal passion and persuasion, becoming the invisible creator of a fictional world, a god that holds the ultimate power over a given reality. In a later work of literary criticism, Vargas Llosa holds up One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967), by his contemporary Gabriel Garcia Marquez, as a prime example of the total novel.

Jean-Paul Sartre and Political Prose. At the same time, Vargas Llosa was also attracted to the way French author and philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre used literature as a tool to pursue a life of political commitment. Some of Vargas Llosa’s early works, such as The Time of the Hero, are clearly inspired by Sartre’s notion that the writer’s role in any given society is to question the established social order relentlessly.

After the Boom. Vargas Llosa’s first two novels, with their innovations in narrative technique, established him as a major influence in Latin American literature, along with his fellow representatives of the ‘‘boom’’ generation. Vargas Llosa has continued to redefine the role of the writer in Latin American society, and, in that fashion, his work has remained contemporary. For example, Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter is in tune with the works of the so-called post-boom generation of writers from the 1970s, including Manuel Puig and Isabel Allende, who immersed themselves in popular culture and expanded the Latin American genre of magic realism.

Works in Critical Context

Mario Vargas Llosa is one of a small handful of the most esteemed Latin American authors of the twentieth century. His novels are widely acknowledged as path-breaking in their narrative complexity and in the social panorama they encompass. Some critics have found the labyrinthine structure of works like Conversation in the Cathedral difficult to comprehend. Others have objected to some of the stylistic pyrotechnics in Vargas Llosa’s fiction, contending that they exist at the expense of character development.

Conversation in the Cathedral. Llosa’s 1969 novel Conversation in the Cathedral, first published in English in 1975, received a range of critical reactions typical of the author’s work. Roger Sale, writing for The Hudson Review, notes that the book ‘‘is huge, almost a quarter of a million words, and it manages that bulk with often amazing skill.’’ Although he claims the story would work better as a film, Sale concludes, ‘‘Conversation in the Cathedral is immensely knowing, and so it makes a reader feel knowing; it is an excellent rather than a moving novel, not great, but very good.’’ Suzanne Jill Levine, in the New York Times Book Review, writes, ‘‘It would be a pity if the enormous but not insurmountable difficulties of reading this massive novel prevent readers from becoming acquainted with a book that reveals, as few others have, some of the ugly complexities of the real Latin America.’’ Other critics were less enthusiastic. For example, Pearl K. Bell of The New Leader calls the book ‘‘such a tiresome, repetitious, logorrheic bore that only in the cruelest nightmare could I imagine myself reading [Vargas Llosa’s] greatly praised earlier works.’’

Responses to Literature

1. Write an essay about the relationship between fact and fiction in Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriter and The Real Life of Alejandro Mayta.

2. Research the life story of Antonio Conselheiro and the bloody battle he and his followers provoked in Brazil. What interpretation does Vargas Llosa give to these events in The War of the End of the World?

3. What relationship do you discern between the evolution of Vargas Llosa’s political views and the development of his literary concerns?

4. Which of Vargas Llosa’s contemporaries had the greatest effect on his style of writing, and in which of his works do you see this being represented?

5. Is there an American author today whom you feel presents a similar biting look at politics in America? Explain your choice.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Booker, M. Keith. Vargas Llosa among the Postmodernists. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1994.

Cano Gaviria, Ricardo. El buitre y el ave fenix: Conversaciones con Mario Vargas Llosa. Barcelona: Anagrama, 1972.

Feal, Rosemary Geisdorfer. Novel Lives: The Fictional Autobiographies of Guillermo Cabrera Infante and Mario Vargas Llosa. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1986.

Gallagher, D. P. Modern Latin American Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1973.

Gerdes, Dick. Mario Vargas Llosa. Boston: Twayne, 1985. Harss, Luis and Barbara Dohmann. Into the Mainstream: Conversations with Latin-American Writers. New York: Harper, 1967.

Lewis, Marvin A. From Lime to Leticia: The Peruvian Novels of Mario Vargas Llosa. Lanham, Md.: University Press of America, 1983.

‘‘Mario Vargas Llosa (1936-).’’ Contemporary Literary Criticism. Edited by Carolyn Riley and Phyllis Carmel Mendelson. Vol. 6. Detroit: Gale, 1976, pp. 543-48.

Moses, Michael Valdez. The Novel and the Globalization of Culture. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Oviedo, Jose Miguel. Mario Vargas Llosa: La invencion de una realidad. Barcelona: Seix Barral, 1982.

Oviedo, Jose Miguel, ed. Mario Vargas Llosa: El escritory la critica. Madrid: Taurus, 1981.

Pereira, Antonio. La concepcion literaria de Mario Vargas Llosa. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, 1981.

Rodriguez Elizondo, Jose. Vargas Llosa: Historia de un doble parricidio. Santiago, Chile: La Noria, 1993.

Rossmann, Charles and Alan Warren Friedman, eds. Mario Vargas Llosa: A Collection of Critical Essays. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1978.

Standish, Peter. Vargas Llosa: La ciudad y los perros. London: Grant & Cutler, 1983.

Periodicals

Americas (March-April 1989): 22; (March-April 1995): 62.

Latin American Literary Review (1983): vol. 11 no. 22: 15-25; (January-June 1987): 121-31, 201-06.

New Yorker (February 24, 1986): 98, 101-04; (August 24, 1987): 83; (December 25, 1989): 103; (October 1, 1990): 107-10; (April 15, 1996): 84.

World Literature Today (Winter 1978) (Spring 1978).