World Literature

P. G. Wodehouse

BORN: 1881, Guildford, England

DIED: 1975, Southampton, New York

NATIONALITY: English, American

GENRE: Fiction, drama

MAJOR WORKS:

Piccadilly Jim (1918)

Mulliner Nights (1933)

Thank You, Jeeves (1934)

Blandings Castle (1935)

Young Men in Spats (1936)

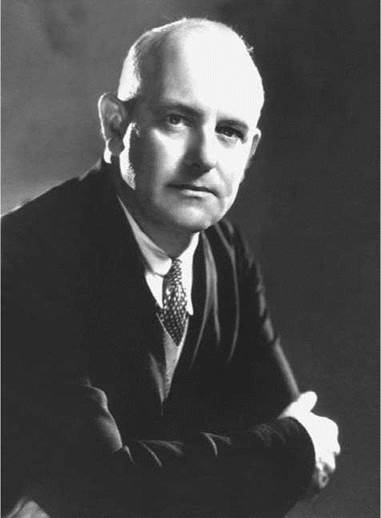

P. G. Wodehouse. Wodehouse, P. G., photograph. AP Images.

Overview

P. G. Wodehouse (pronounced like ‘‘Woodhouse’’) is an anomaly in twentieth-century fiction. In an age of relentless artistic experimentation, he wrote fiction firmly rooted in the Edwardian world of his childhood. In an age of rapidly changing moral and sexual values, he created characters and situations remarkable for their purity and innocence. In an age of seriousness, he wrote fiction designed solely for amusement. In an age of artistic anxiety and alienation, Wodehouse wrote novels and short stories that succeeded in pleasing his readers, his critics, and himself.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

A Dulwich Impression. Pelham Grenville Wodehouse was born on October 15, 1881, the third of four sons of Henry Ernest Wodehouse, a member of the British civil service in Hong Kong, and Eleanor Deane Wodehouse, the daughter of Rev. Deane of Bath. Sent back to England for schooling in 1884 with his older brothers, Wodehouse began his education at Bath. Wodehouse told Paris Review interviewer Gerald Clarke, ‘‘I was writing stories when I was five. I don’t remember what I did before that. Just loafed, I suppose.’’ Wodehouse attended Elizabeth College in Guernsey before enrolling in Malvern House, a navy preparatory school, in Kearnsey. His most important educational experience began at the age of twelve when he began attending Dulwich College, where he studied for six years. During his last year there, he received his first payment for writing ‘‘Some Aspects of Game Captaincy,’’ an essay that was a contest entry published in the Public School Magazine. Wodehouse recognized the important influence of Dulwich College on his life and later wrote to friend Charles Townsend that ‘‘the years between 1896 and 1900 seem[ed] like Heaven’’ to him.

Oxford Detour. Wodehouse could not proceed to Oxford University—the usual path for a boy of his background—because his father’s pension was paid in rupees, the value of which fell so drastically at the time that the family could not afford another son at the university, even if a scholarship had been available. Wodehouse already knew he wanted to write and suggested that he become a freelance writer, but his father would not hear of such impracticality. Wodehouse became a clerk at the London branch of the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank, a training post for those to be sent to the Far East. His time as a clerk proved not entirely unproductive: During his tenure at the bank he sold eighty stories and articles, primarily sports-related articles for the Public School Magazine.

American Humor. Wodehouse always recalled that a ‘‘total inability to grasp what was going on made me something of a legend’’ in the bank, and he soon entered the more congenial profession of journalism. He was first a substitute writer for the ‘‘By the Way’’ column in The Globe, and by August 1903 he was employed full-time by the paper. Fascinated with boxers and wanting to meet James J. Corbett and other fighters, Wodehouse fulfilled a longtime ambition by making his first trip to America, arriving in New York in 1904. After a short stay, he returned to England as editor of the ‘‘By the Way’’ column, but his love for America, and for the possibilities he felt it promised writers, remained with him. In a 1915 New York Times interview with Joyce Kilmer, Wodehouse predicted that the years following World War I would ‘‘afford a great opportunity for the new English humorist who works on the American plan.’’

Wodehouse eventually seized this opportunity and exploited it so well that years later one reviewer of Young Men in Spats (1936) remarked that Wodehouse was ‘‘the only Englishman who can make an American laugh at a joke about America.’’ The reviewer reasoned that the real secret of Wodehouse’s American popularity was that he really liked Americans. One American whom Wodehouse particularly liked was Ethel Newton Rowley, a widow with one child named Leonora. Wodehouse had met Ethel on one of his visits to America, and he married her on September 30, 1914.

Minor Hollywood Scandal. In 1904, Wodehouse ventured into theatrical writing when Owen Hall asked him to compose lyrics for a song in the show Sergeant Bruce. Wodehouse responded with ‘‘Put Me in My Little Cell,’’ sung by three crooks. In 1906 Sir Seymour Hicks hired Wodehouse as lyricist for his Aldwych Theatre shows, the first of which, The Beauty of Bath, also marked his initial collaboration with Jerome Kern. When Kern introduced Wodehouse to Guy Bolton in 1915, the three men shared ideas about a new kind of musical comedy and decided to join forces to create what became known as the Princess Theatre shows. The Kern-Bolton- Wodehouse team set new standards for musical comedy.

Throughout the 1920s Wodehouse’s work as a journalist, lyricist, and fiction writer made him increasingly famous and wealthy, and his success inevitably attracted the attention of Hollywood. In 1930, after being subjected to the typically shrewd business negotiations of Ethel Wodehouse, Samuel Goldwyn offered Wodehouse two thousand dollars a week for six months, with a further six-month option. Wodehouse’s contribution amounted to little more than adding a few lines to already-completed scripts, and this caused him to tell an interviewer for the Los Angeles Times that ‘‘They paid me $2000 a week—$104,000—and I cannot see what they engaged me for. They were extremely nice to me, but I feel as if I cheated them.’’

Wodehouse’s remarks caused a minor scandal and were said to have caused New York banks to examine studio expenditures more closely. That he actually negatively impacted Hollywood finance seems doubtful, especially since three years after the Los Angeles Times interview, he was asked to return to Hollywood. His final film project in 1937 was not a success, and that year Wodehouse left Hollywood for good. Film scripts constitute the only type of writing Wodehouse attempted without success, but the Hollywood experience did give him abundant material for his later fiction.

The Hollywood experience aside, the 1920s and 1930s were remarkably productive and successful years for Wodehouse. It was also during these years that he wrote some of his best short stories, especially the Mr. Mulliner tales, which are driven by a golf theme and told by ‘‘The Oldest Member.’’ Wodehouse’s best- known short stories, however, are those devoted to his beloved characters Bertie Wooster and Jeeves, his valet. In each of these tales, Jeeves must rescue the ridiculous Bertie from various absurd situations.

American Broadcasts. Shortly after Wodehouse was honored by being made a doctor of letters by Oxford University in 1939, he was unable to escape Le Touquet, France, where he was living at the time that France fell to the rapidly advancing Nazi German army. On July 21, 1940, Germany decreed that all male aliens were to be interned, and Wodehouse was imprisoned in Tost (now Toszek), Upper Silesia. In June 1941, when Wodehouse was to be released, CBS correspondent Harry Flannery arranged for Wodehouse to broadcast to America from a script Flannery had written.

It was not long before the German Foreign Office asked Wodehouse to make a series of broadcasts to America using his own scripts. He agreed and broadcast a series of talks called ‘‘How to Be an Internee in Your Spare Time Without Previous Experience.’’ These talks treated his experiences in prison camp with his usual humor, and what he read today seems harmless enough. However, the reactions of British press and government approached hysteria at the time. William Connor of the Daily Mirror accused ‘‘the elderly playboy’’ of broadcasting Nazi propaganda, though Connor never mentioned what Wodehouse actually said in the broadcasts. Ironically, the U.S. War Department used recordings of the broadcasts as models of anti-Nazi propaganda in its intelligence school, but members of the British government remained unforgiving.

After this bitter experience, Wodehouse left England for New York in 1947. He seldom spoke of the broadcasts later and, at least publicly, held no grudges. He became an American citizen in 1955 and never returned to England, although he frequently discussed doing so, especially when he was granted a knighthood on New Year’s Day 1975. He remained on Long Island, New York, where he lived a happy life ‘‘just writing one book after another.’’ He was working on another novel, Sunset at Blandings, when he died on February 14, 1975.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Wodehouse's famous contemporaries include:

Scott Joplin (1867-1916): This famous American composer was innovative in Ragtime music.

Louis B. Mayer (1882-1957): Mayer, an American film producer, cofounded one of the first film studios, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM).

George Orwell (1903-1950): This celebrated English author and journalist concerned himself with government, politics, language, and the oppression of censorship.

Frank Sinatra (1915-1998): Sinatra was a popular American singer and award-winning actor known as ''Ol' Blue Eyes.''

James Thurber (1894-1961): Thurber was an American writer, humorist, and cartoonist.

Works in Literary Context

Comic Wordplay. In his school stories, Wodehouse used materials from conventional novels, enhancing his stories with literary allusions and quotations that became characteristic features of his later work. In his work of the 1920s and 1930s, he introduced his most characteristic devices: a mixture of convoluted plots; comic timing; stereotypical characters; and above all, his own invented language. Such language consists of odd personifications, a thorough confusion of vocabulary, an abundance of puns, and wild similes and metaphors that transport both characters and readers far beyond the bounds of logical discourse.

One way Wodehouse manipulates language to achieve comic effect is by adding and omitting prefixes and suffixes. For example, he takes the prefix de-, as in debunk or delouse, and adds it to proper names. The effect is witty and humorous, as seen in Uncle Dynamite when Pongo Twistleton gets Elsie Bean out of a cupboard: ‘‘His manner as he de-Beaned the cupboard was somewhat distrait.’’ Another example can be observed in Jeeves in the Offing when Bobbie Wickham has left Kipper Herring alone: Herring was ‘‘finding himself de-Wickhamed.’’

Wodehouse’s use of language to evoke humor can also be seen in the Jeeves and Bertie stories. Even though Bertie is a highly educated person, he has a limited vocabulary and either haltingly tries to remember the ‘‘right’’ word or depends on Jeeves to complete his thoughts for him by providing the appropriate word. For instance, in Stiff Upper Lip, Bertie says, ‘‘I suppose Stiffy’s sore about this ... what’s the word?... Not vaseline ... Vacillation, that’s it.’’ In Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit, Bertie says, ‘‘Let a plugugly young Thos loose in the community... [is] inviting disaster and ... what’s the word? something about cats.’’ Jeeves replies, ‘‘Cataclysms, sir?’’ The results are amusing.

Influences. The enormous influence of Dulwich College in Wodehouse’s work has long been recognized. J. B. Priestley voiced the sentiment that Wodehouse remained ‘‘a brilliant super-de-luxe schoolboy’’ throughout his life, a belief that explains the sexless young women, terrifying aunts, and eccentric aristocrats who fill his pages. Another great influence on Wodehouse’s fiction, especially his short stories, was his theatrical writing. In Over Seventy (1956), Wodehouse names several other humorists he greatly respected, including Alex Atkinson, A. P. Herbert, and Frank Sullivan.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Wodehouse's incomparable wit was his trademark. Other works known for their comic appeal include:

Barrel Fever (1994), a collection of stories by David Sedaris. Noted humorist David Sedaris won widespread acclaim and attention with this collection.

The Importance of Being Earnest (1895), a play by Oscar Wilde. In this comedy of manners, misunderstandings and misinformation create a comic situation akin to Wodehouse's later Jeeves and Wooster tales.

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1925), a novel by Anita Loos. This comic novel about the substantial power of a gold-digging blonde was turned into a successful 1953 movie starring Marilyn Monroe.

Works in Critical Context

Wodehouse Collaborated Musicals. As early as 1935, Frank Swinnerton offered a remark that is surely the best praise a humorist can receive: Wodehouse was so popular because ‘‘in a period when laughter has been difficult, he has made men laugh without shame.’’ Wode- house did not receive much critical attention during his career, and he described himself as ‘‘a pretty insignificant sort of blister, not at all the type that leaves footprints on the sands of time,’’ because ‘‘I go in for what is known in the trade as ‘light writing’ and those who do that— humorists they are sometimes called—are looked down upon by the intelligentsia and sneered at.’’ Other writers, however, not to mention millions of readers, have found in Wodehouse’s world a wonderful escape from their own. Evelyn Waugh, in a broadcast of July 15, 1961, explained Wodehouse’s continuing attraction: ‘‘For Mr. Wodehouse there has been no Fall of Man, no aboriginal calamity.... Mr. Wodehouse’s world can never stale.’’

The Kern-Bolton-Wodehouse team of 1915 set new standards for musical comedy. The Oxford Companion to the American Theatre asserts that Wodehouse ‘‘may well be considered the first truly great lyricist of the American musical stage, his easy colloquially flowing rhythm deftly intertwined with a sunny wit.’’ The Princess Theatre shows, though highly successful and influential in their time, are now seldom-revived period pieces. Their real and lasting influence was not only on audiences but on Wodehouse’s fiction, which he subsequently began to structure in the fashion of the musical comedy. According to scholar David Jasen, Wodehouse himself ‘‘described his books as musical comedies without the music.’’

Responses to Literature

1. Using your library and the Internet, find out more about the roles of household servants to upper-class British families in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. What roles were fulfilled by such servants as the housekeeper, the butler, and the valet? How many servants did the typical household employ? Do upper-class families in England continue to employ such servants today?

2. Gentleman’s clubs feature prominently in Wodehouse’s fiction. Using your library and the Internet, find out more about one of London’s historic gentleman’s clubs and write a short summary of its history.

3. Wodehouse’s Jeeves stories were adapted for television in the Independent Television series Jeeves and Wooster (1990-1993), which starred Stephen Fry and Hugh Laurie. Watch some of the episode of this series. Do you think the television shows capture the humor of Wodehouse’s writing? Are the portrayals of antics of British aristocrats affectionate or critical?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Bordman, Gerald. Oxford Companion to American Theatre. New York: Oxford University Press USA, 2004.

Jasen, David A. A Bibliography and Reader’s Guide to the First Editions of P. G. Wodehouse. Peoria, Ill.: Spoon River Press, 1986.

Wodehouse, P. G. Life With Jeeves (A Bertie and Jeeves Compendium). New York: Penguin, 1983.

________. Over Seventy. London: Herbert Jenkins Press, 1957.

________. Uncle Dynamite. New York: Overlook Press Hardcover, 2007.

Periodicals

Clarke, Gerald. Paris Review (Winter 1975).

Kilmer, Joyce. New York Times (February 15, 1975); (October 18, 1981); (November 12, 1984); (November 7, 1985); (October 20, 1987); (March 23, 1989).

Los Angeles Times (June 7, 1931).

Web sites

Books and Writers. Sir P(elham) G(renville) Wodehouse (1881-1975). Retrieved February 14, 2008, from http://www.kirjasto.sci.fi/pgwod.htm.

Lawrie, Michael. Cassandra [William Connor] and P. G. Wodehouse. Retrieved February 14, 2008, from http://lorry.org/cassandra.

The Wodehouse Society (TWS). Official P. G. Wodehouse Website. Retrieved February 14, 2008, from http://www.wodehouse.org. Last updated on May 17, 2007.