World Literature

Lu Xun

BORN: 1881, Shaoxing, China

DIED: 1936, Shanghai, China

NATIONALITY: Chinese

GENRE: Fiction, nonfiction, poetry

MAJOR WORKS:

‘‘Diary of a Madman’’ (1918)

The True Story of Ah Q (1927)

Selected Stories of Lu Xun (1954)

Dawn Blossoms Plucked at Dusk (1976)

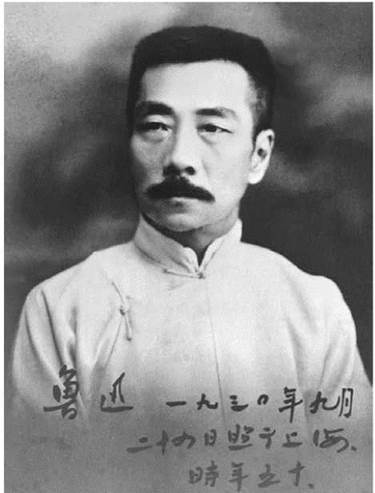

Lu Xun. © Bettmann / CORBIS

Overview

Chinese writer Lu Xun is widely regarded as the founder of modern Chinese literature. His writings addressed important political and cultural issues associated with communism and the modernization of China. His story ‘‘Diary of a Madman’’ was published in 1918, and is one of the more famous stories in the canon of Chinese literature.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

A Strong Mother. Lu Xun was the pen name of Zhou Shuren, who was born September 25, 1881, into a poor but educated family in the Zhejiang province of China. He and his two younger brothers received a classical Chinese education based on Confucian texts. His family’s financial situation deteriorated during his early years because of his grandfather’s imprisonment for bribery; family resources were exhausted in appeals for clemency for his grandfather. Then his father died during his teenage years. Lu Xun’s mother, educated and independent, held the family together during Lu Xun’s first seventeen years and had a powerful influence on him throughout his life.

Education and Loss of Heart. As was typical of many intellectuals of his generation, Lu Xun chose other educational paths after his early grounding in Confucianism. After studying briefly in the Jiangnan Naval Academy in Nanking in 1898, he transferred to the School of Railways and Mines, graduating in 1901. He then won a government scholarship to study medicine in Japan. After two years of Japanese language study in Tokyo, he entered the Sendai Provincial Medical School in the summer of 1904.

In the early twentieth century, China was a country in the midst of great transformation. Beginning with the Boxer Rebellion of 1900 (in which the peasantry revolted against foreigners), and moving on to the Russo-Japanese War, the Revolution of 1911 (which ended the Ch’ing Dynasty), the New Culture Movement (which spurned traditionalism and embraced social democracy), and the May Fourth Movement of 1919 (which sought national independence and individual freedoms), China was redefining itself in many ways. It was this shifting political and social landscape that inspired and colored Lu Xun’s writing.

Thus, after witnessing the humiliation of China in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, Lu Xun turned his attention to writing as a means of awakening the Chinese people to the need for revolution. The major essays of his early period were published in 1908 in Henan. In one essay, he analyzes the rise and problems of the West, drawing conclusions relevant to China’s modernization process. In another he criticizes China’s gentry for blaming the country’s backwardness on the ‘‘ignorance and superstition’’ of the peasants, rather than admitting their own responsibility. Henan was banned by the Japanese government at the request of the Qing authorities before Zhou could publish a sequel.

Disappointed by the failure of the masses to respond to his writings, however, and discouraged by the failure of the Revolution of 1911, Lu Xun abandoned his crusade and spent most of the years 1909 to 1919 publishing studies of traditional Chinese literature and art.

Writing Success. After Lu Xun’s return to China, he took a job teaching in his hometown. When the 1911 revolution began, Zhou was teaching in a middle school in Shaoxing. He was among the first to realize that though the Qing Dynasty had been overthrown, little else had changed. In fact, warlords, old-style gentry, and opportunists of every sort took over the government at the national and local levels, and the weak, far from being liberated, became victims. He addresses the failure of the revolution in several of his short stories and particularly with the black humor of his novella ‘‘A Q zheng zhuan’’ (1923), translated as ‘‘Our Story of Ah Q,’’ (1941).

In April 1918, Lu Xun began to contribute stories to Xin qingnian (New Youth), a liberal magazine with a nationwide circulation; it was a principal mouthpiece of the New Culture movement, which was closely allied with the May Fourth Movement. He first used the pen name Lu Xun for the story ‘‘Kuangren riji’’ (translated as ‘‘Diary of a Madman,’’ 1981) in the May 1918 issue of Xin gingnian. In keeping with the New Culture movement, the short story was critical of traditional Confucian ideas. It was the first significant Chinese literary effort that was written in the vernacular, as opposed to the elevated prose of traditional literature, and for this reason, Lu Xun is regarded as the father of modern Chinese literature.

Impact on China. Lu Xun went on to write many more major short stories, essays, poems, and literary criticism in the vernacular style. Among the most celebrated of these were ‘‘The True Story of Ah Q,’’ and ‘‘The New Year’s Sacrifice,’’ (1924), which looked at the oppression of women. His influence was such that by the turn of the twenty-first century, Lu Xun’s works had been translated into approximately fifty languages and published in over thirty countries.

Lu Xun’s politics were decidedly leftist throughout his life, although he declined to ever formally join the Chinese Communist Party. His support for the 1926 Beijing student rebellion forced him to leave the city, and he settled in Shanghai in the late 1920s. There he continued to write and work, while serving as the head of the League of Left-Wing Writers. He founded a magazine, the Torrent, in 1928 and edited others. On October 19, 1936, Lu Xun died of tuberculosis, a highly contagious disease that affects the lungs.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Lu Xun's famous contemporaries include:

Zhu De (1886-1976): Chinese statesman who founded the Chinese Red Army.

Hu Shi (1892-1962): Essayist who promoted the Vernacular Chinese style, which made writing accessible to the less educated.

Mao Zedong (1893-1976): Controversial Communist leader of the People's Republic of China.

Allen Ginsberg (1926-1997): Famous American Beat poet who openly idealized China and praised communism.

Works in Literary Context

Lu Xun wrote poetry, short stories, and essays. While his essays tend to be dry and sardonic, his prose is introspective. In addition to writing about his characters—their appearance, personality traits, and actions—Lu Xun delved into the inner conciousness of his characters. He wrote extensively about what his characters were thinking and feeling. One of Lu Xun’s most memorable characters is Ah Q.

The Everyman. Ah Q is a peasant who views himself as a winner. He is a new Everyman, an international symbol of human folly whose penchant for self-delusion is evident: Whenever he is humiliated by a rival, he quickly turns the experience around in his mind and imagines himself to have come out on top. ‘‘The True Story of Ah Q’’ is often read as a national allegory, though when it was published, several individuals thought themselves to be the butt of the satire; some wrote letters to the newspaper in protest.

Tradition and Superstition. In ‘‘The New-Year Sacrifice,’’ (1981), Lu Xun confronts the May Fourth movement, which rejected traditional literature and applauded modern prose. The narrator is an intellectual who has come home for a visit and worries about a peasant woman, a widow whose son was carried off by a wolf. She presses the narrator with the question, ‘‘When people die, do their souls live on?’’ Not knowing the context of her question and hoping to comfort her, he suggests that there may, indeed, be life after death. The answer only increases her anxiety. The story ends with a passage describing the narrator’s reaction to the Lunar New Year celebration immediately after her death.

Much of the story has to do with the narrator’s inability to communicate meaningfully with the townspeople; thus, it encapsulates the tragedy not only of the peasant woman but also of China’s modern intelligentsia and their inability to change, or even influence, conditions in the country.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Lu Xun wrote much about communism. Though he did not agree with the entire philosophy, he saw virtue in some of the political ideals it espoused. Here are some other works that explore the successes and failures of communist philosophy.

The Battleship Potemkin (1925), a film by Sergei Eisenstein. This silent film details the mutiny of a crew of Russian sailors.

The Master and Margarita (1941), a novel by Mikhail Bulgakov. Satan wreaks havoc in Stalin's Soviet Union in this political satire.

''America'' (1956), a poem by Allen Ginsberg. In this poem, written during the cold war, Ginsberg's speaker openly admits his affiliation with and admiration of the Communist Party.

Reds (1981), a film by Warren Beatty. This movie is about the short life of an American journalist who covered the Russian Revolution.

Works in Critical Context

Lu Xun’s initial fame rested on a series of sometimes bleak, sometimes humorous, often satirical short stories written in the modern Chinese vernacular. He gained renewed fame and influence as a master of the feuilleton, which he wielded as a rhetorical dagger first against the warlord government in Beijing in the late 1920s and then in the 1930s against the Nationalist Party. He was not afraid to use his pen against oppression and express his ideological concerns.

Commenting on the author in a Xinhua News Agency article, Kitaoka Masako noted: ‘‘Without a thorough understanding of Lu Xun, it’s impossible to know about China.’’ In the same article, Maruyama Noboru commented that ‘‘The works of Lu Xun and the spirit they carried have transcended every impediment on ideology and last far beyond his age.’’

‘‘Diary of a Madman”. Lu Xun’s first short story, ‘‘Diary of a Madman,’’ was written in modern Chinese. This groundbreaking story is considered one of the first Western-style stories in China. The story established the theme with which Lu Xun became identified by most of his Chinese readers: the denunciation of traditional ethical codes as hypocritical cant formulated by the oppressors to justify an inhumane order that permits the strong to prey on the weak.

A contributor to the Pegasos Web site noted: ‘‘The narrator, who thinks he is held captive by cannibals, sees the oppressive nature of tradition as a ‘man-eating’ society.’’ The writer added that the author’s ‘‘tour de force helped gain acceptance for the short-story form as an effective literary vehicle’’ in China. Lu Xun later wrote that he had used cannibalism in this story as a metaphor for exploitation and inhumanity.

‘‘The True Story of Ah Q’’. Lu Xun’s most famous story, ‘‘The True Story of Ah Q,’’ tells the tale of a poor, uneducated farm laborer who not only suffers but seems to readily accept a series of humiliations that finally end in his execution during the 1911 revolution. Throughout his ordeals, the protagonist blames himself for his troubles or holds on to a misguided belief that it all must be for the better. ‘‘It is a mentality that people recognize as universal,’’ commented Sue Fan in an article by Sandy Yang in the Daily Bruin of the University of California at Los Angeles. ‘‘By looking at human nature, we all have our way of rationalizing our actions. It is a survival mechanism to look at the brighter side of things even when you’re being humiliated.’’

In a critical essay in East Asia: An International Quarterly, Rujie Wang called the tale ‘‘a brilliant satire’’ and went on to note: ‘‘In Lu Xun’s text, everybody, Ah Q as well as the villagers of Weizhuang, prefers existing knowledge to anything new and original. No one in the village is bothered with finding the truth of what really goes on.’’ Wang added, ‘‘As an absurd hero whose tragedy has absolutely no redeeming qualities, Ah Q exists to ridicule the views and values the anti-traditionalist intellectuals have gladly declared bankrupt, values which have been affirmed in the past by many tragic heroes confronted with similar calamities.’’

Responses to Literature

1. Compare and contrast ‘‘Diary of a Madman’’ and ‘‘Upstairs in a Wine Shop.’’ In your analysis, consider how traditions and modernism are viewed by the characters. Explain the meaning of Lu Xun’s line ‘‘Save the children.’’

2. After reading ‘‘The True Story of Ah Q,’’ discuss Ah Q’s view of his situation. What message do you think the author is making about Chinese traditions?

3. Lu Xun often chose to write satirically. Discuss why satire is a suitable approach when writing about politics.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Hsia, Tsi-an. The Gate of Darkness: Studies on the Leftist Literary Movement in China. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1968.

Huang, Songkang. Lu Hsiin and the New Culture Movement of Modern China. Amsterdam: Djambatan, 1957.

Kowallis, Jon Eugene von. The Lyrical Lu Xun: A Study of His Classical-Style Verse. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1996.

Lu Xun. Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 328: Chinese Liction Writers, 1900-1949. A Bruccoli Clark Layman Book. Middlebury College. Ed. Thomas Moran. Detroit: Gale, 2007, pp. 129-50.

Lyell, Jr., William A. Lu Hsun’s Vision of Reality. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1976.

Wang, Shiquing. Lu Xun: A Biography. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1984.

Periodicals

Duke, Michael S. ‘‘The Lyrical Lu Xun: A Study of His Classical-Style Verse.’’ World Literature Today, (Winter 1998): 203.

Wan, Rujie. ‘‘Lu Xun’s ‘The True Story of Ah Q’ and Cross-Writing.’’ East Asia: An International Quarterly, (Autumn 1998): 5.

Xinhua News Agency, (April 21, 2001); (October 7, 2001); (October 28, 2001); (December 20, 2001).

Yang, Sally. ‘‘Tale Cues in Essence of Individuality; Performance: ’Ah Q’ Combines Dance, Theater to Critique Human Nature.’’ Daily Bruin (University of California, Los Angeles), (December 3, 1998).

Koizumi Yakumo

SEE Lafcadio Hearn