World Literature

Aeschylus

BORN: 524 BCE, Eleusis, Greece

DIED: 456 BCE, Gela, Italy

NATIONALITY: Greek

GENRE: Drama

MAJOR WORKS:

Persians (472 BCE)

Seven Against Thebes (467 BCE)

Oresteia (458 BCE)

Prometheus Bound (unknown)

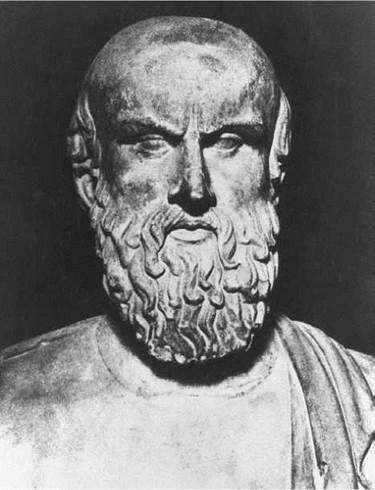

Aeschylus. Aeschylus, photograph. AP Images.

Overview

Considered the founder of Greek tragedy, Aeschylus is said to have set the paradigm for the entire genre in Western literature. His tragedies, exemplified by such seminal works as Prometheus Bound and the Oresteia trilogy, are widely praised as thoughtful and profoundly moving translations of tremendous feelings into the sublime language of poetry. Unfortunately, only seven plays of Aeschylus have survived intact.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

A Noble Family. Aeschylus, the son of Euphorion, was born in 524 BCE, of a noble family with Athenian citizenship in the deme, or village, of Eleusis. Not far from the growing city of Athens, Eleusis was sacred to the two goddesses of grain, Demeter and her daughter Persephone. It was also the center for the Eleusinian Mysteries, a principal mystery religion in ancient Greece. In 534, about ten years before Aeschylus was born, the Athenian dictator Peisistratus transferred the cult center of Dionysus Eleuthereus (‘‘of Eleutherae,’’ a village on the border of Attica) to downtown Athens, just south of the Acropolis. Here Peisistratus instituted an annual festival, the Great or City Dionysia, which included public performances where songs and dances by a chorus alternated with solo recitations by a poet. In each performance, poet and chorus explored themes from the Greek myths. Before the end of the century the satyr play, a mythological farce, was added to the festival, and tragedians competed for a prize for the best play. Aeschylus began competing in 498, but did not win his first victory at the City Dionysia until 484. The success he enjoyed as a playwright for most of the fifth century was won after years of failure. Aeschylus married and had two sons, Euphorion and Euaeon, both of whom became tragic poets.

The Battle of Marathon. When Aeschylus was a young man, the armies of the Persian Empire—based in the region now known as Iran—were advancing across the city-states of Greece toward Athens. The Persians had already conquered regions to the east of Attica—where Athens and Eleusis were located—and with the superior numbers of the Persian forces, many were expecting all of Greece to become yet another territory of the Persian Empire. Aeschylus, along with thousands of other Greeks, gathered at the Plain of Marathon on the eastern coast of Attica to fend off the Persian army. Ancient sources state that the Persian soldiers were anywhere from two hundred thousand to six hundred thousand in number, though modern estimates have been much lower. The Greek forces were certainly outnumbered; however, through skillful maneuvering on the battlefield, they drove the Persian armies back to the sea with only about two hundred soldiers lost. According to some accounts, one of those lost was Aeschylus’s brother Kynaigeirus. The battle was considered a decisive victory for the Greeks, and it inspired Aeschylus to write a play titled Persians.

Persecution. Aeschylus’s plays, often noted for their religious and theological themes, concentrate on the great Panhellenic gods, with Zeus as ruler over Hermes, Apollo, Aphrodite, and Athena. Ancient authors thought it significant that Eleusis, where Aeschylus was born, was the religious center for the Eleusinian Mysteries, a mystery religion of great importance in ancient Greece. This religion was one that prohibited its followers from revealing its teachings and its rituals. In the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle relates that Aeschylus was impeached for revealing the secrets of the Mysteries but pleaded ignorance. In the third century CE, Christian writer Clement of Alexandria interpreted Aristotle’s point to mean that, despite his Eleusinian origins, Aeschylus was never initiated into the Mysteries. His plays confirm the idea that his religious commitments were Olympian and Hellenic, not local.

According to Heracleides of Pontus, a pupil of Aristotle, the playwright was alleged to have revealed secrets of the Mysteries in his play Prometheus Bound; the audience of the play tried to stone Aeschylus, and the playwright took refuge. Aeschylus was later acquitted.

Reminiscences. Although little more is known or verifiable about Aeschylus’s personal life, some reminiscences of Aeschylus have survived. Ion of Chios, a younger tragedian, recorded in his Visits that he watched a boxing match at the Isthmian Games with Aeschylus, and that one boxer received a terrible blow that made the crowd roar. ‘‘You see the importance of practice,’’ said Aeschylus, nudging him. ‘‘The one who was hit is silent, but the spectators cry out.’’ Ion may also be the source for Aeschylus’s comment that his plays were ‘‘slices of fish from Homer’s great feasts.’’ Aristotle’s pupil Chamaeleon reports a story that Sophocles told Aeschylus: ‘‘Even if you write what is appropriate, you do not know what you are doing when you compose.’’ The second-century CE author Athenaeus connected this remark with the story that Aeschylus composed while drunk, a story that sounds as if it might be “biographical fiction’’—bio- graphical information that is created from popular stories about a figure but that lack credibility.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Aeschylus's famous contemporaries include:

Sophocles (496-406 BCE): Greek playwright whose most famous works focus on the life of Oedipus, including Oedipus Rex and Antigone.

Darius (549-485 BCE): Persian king who attempted to assert his rule over Athens in 490 BCE. His attempt was soundly thwarted.

Xerxes (519-465 BCE): Persian king and successor of Darius. Like his predecessor, Xerxes tried to invade Greece. Xerxes's attempt on Greece is retold, in part, in the 2006 film 300.

Tarquin the Proud (?-496 BCE): Last king of Rome. Upon his deposition, Rome turned into a republic, by many accounts the first of its kind, with elected officials, rather than dictators chosen based on their ancestry.

Pythagoras (c. 572-c. 490 BCE): Greek mathematician. Not only was Pythagoras important in introducing mathematics as a subject of study, his work, including the Pythagorean Theorem, is still a cornerstone of modern mathematics.

Gautama Siddhartha (563-483 BCE): A spiritual leader in India better known simply as the Buddha.

Confucius (551-479 BCE): Chinese philosopher and writer whose wisdom can be found codified in the Analects.

Works in Literary Context

Given that Aeschylus wrote during the formative period of Greek theater and that no older dramas have survived, it is difficult to assess just how important Aeschylus was to the development of Greek tragedies for his contemporaries. However, Aristotle, writing a little over a century after Aeschylus’s death, vouched for his importance in the history of the theater. Further, his continuing influence on composers and playwrights up to and including the twentieth century vindicates the important role attributed to Aeschylus in the development not only of tragedies but also of opera.

Aeschylus’s Drama: His Innovations. Although Aeschylus is the first playwright whose work has survived, he was not the first Athenian playwright. Much can never be resolved about the origins and earliest form of Greek tragedy, but it is widely accepted that tragedies were first performed at the festival of the Great Dionysia in about 534 BCE. This was several years before Aeschylus was born. What form such tragedies took is also largely a matter of conjecture but Aristotle was later to credit Aeschylus with introducing a second actor. If nothing else this confirms that previous tragedy had been performed by a single actor with a chorus and that Aeschylus’s first work was of this nature. Aristotle goes on to state that Sophocles was the originator of the third actor and Aeschylus has clearly accepted the development by the time of the Oresteia in 458 BCE.

The importance of using more than one actor in a play may not be immediately apparent, but consider the effects one can achieve with multiple actors on stage at the same time. With only a single actor, a character can only have as his or her audience the chorus or the actual audience in attendance. However, when a playwright adds additional actors to a play, he or she is able to show the interaction between characters in order to attain higher levels of irony and tension, as audiences will inevitably be forced to evaluate the goodness or badness of each character. When a third character is added to a play, the possibilities continue to expand, for with three actors it is possible, for instance, for one to be hiding and listening to the other two without their knowing it. Consider the famous scene from Hamlet in which Hamlet is speaking with his mother in her bedroom while Polonius listens in. In this moment, the scheming of Hamlet’s uncle and mother come to a head and Hamlet’s madness is confirmed when he strikes Polonius dead, supposedly thinking he is slaying a rat running around behind the curtains of his mother’s window. This climactic moment in Shakespeare’s play would be impossible without Aeschylus’s innovations.

Because Aeschylus was writing for the Greek theater in its formative stages, he is also credited with having introduced many features that became associated with the traditional Greek theater. Among these were the rich costumes, decorated cothurni (a kind of footwear), solemn dances, and possibly elaborate stage machinery.

Legacy. The ninety plays that Aeschylus wrote were performed frequently after his death, and the tragic drama remained a living tradition in the hands of his successors, Sophocles and Euripides. Tragedy also exerted a decisive influence on the development of literary criticism: Aristophanes’ comedy The Frogs (405 BCE) is devoted to comparing and contrasting the tragic art of Aeschylus and Euripides, and both the literary form and specific tragedies were analyzed in Aristotle’s profoundly influential treatise, Poetics (late fourth century BCE). Later, imitations of Greek tragedy written in the first century CE by the Roman playwright Seneca exerted a powerful influence on the development of European theater during the Renaissance. Tragedy’s uniting of music and drama became the guiding inspiration in the creation of opera, and Aeschylus’s work provided a model for major compositions by Richard Wagner.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Aeschylus's play Persians deals with the historical figure Xerxes and how his hubris—extreme confidence—leads to his ultimate demise. Arrogance has long been one of the key subjects of literature and art. Aeschylus himself was undoubtedly familiar with Homer's Iliad, the primary events in which are set in motion by the hubris of Agamemnon and Achilles, two soldiers who battle over women and fame. Here are some other works that have hubris as their focus:

Macbeth (c. 1603), a play by William Shakespeare. In this play, one can understand Macbeth's fateful and murderous ambition as cultivated by his hubris—his supreme pride.

Moby-Dick (1851), a novel by Herman Melville. The unforgettable Captain Ahab pursues the white whale Moby-Dick to the point of self-destruction in Melville's classic.

Absalom, Absalom (1936), a novel by William Faulkner. Thomas Sutpen attempts to create a dynasty for himself in this Southern gothic novel.

Citizen Kane (1941), a film by Orson Welles. Welles wrote, directed, and starred in this film about the rise of fictional publishing magnate Charles Foster Kane.

Works in Critical Context

Aeschylus’s work earned him a number of awards, and after his Persians was performed, Hieron, dictator of Gela and leader of the Greeks in Sicily, invited Aeschylus to stage the play in Gela. He also later commissioned Aeschylus to write Aetnean Women to celebrate the refounding of the city of Etna. In other words, Aeschylus did not labor in obscurity but was honored by the critics of his time. His impact on theater is still felt today, and his Oresteia is still considered a great companion piece for Homer’s Iliad, the inspiration for Aeschylus’s trilogy.

Persians. Aeschylus uses in this play, although not for the first time, two actors in addition to the chorus and its leader. The original addition of a second actor in the Greek theater was attributed to Aeschylus by Aristotle, who had made a survey of early drama for his Poetics. The second actor, by increasing opportunities for contrast and conflict, was essential for the development from choral performance to drama. The costumes ranged from impressive outfits for the chorus, Queen Mother, and Darius to Xerxes’ torn rags. The play builds from suspense to resolution. The emotions range from fear to pity. Greek literary critics from Gorgias to Aristotle saw this range of emotions as typical of tragedy. When the play was first performed at the Dionysia in 472 BCE, it won first prize. The play remained popular in the decades after the author’s death—Aristophanes even mentions it in one of his most famous plays—and the fact that it is one of the few plays of Aeschylus to survive to modern times is an indication of the regard in which it was held.

Oresteia. In 458 BCE, Aeschylus produced the Oresteia, which is the only surviving Greek trilogy and probably the playwright’s last work. Oresteia includes the plays Agamemnon, Libation Bearers, and Eumenides, and the lost satyr play Proteus. As both poetry and drama, the Oresteia is generally held to be Aeschylus’s masterpiece and one of the greatest works of world literature. Its themes are presented with a power of poetry and a theatrical verve and creativity that are unprecedented. The chorus of the Furies in Eumenides was remembered for generations. The third actor and a new stage set are used with startling originality and impact to underline the plays’ themes. These four plays of Aeschylus are the first plays that were written for the set on which tragedy was performed for the rest of the fifth century.

Responses to Literature

1. In classical as well as contemporary literature, hubris is a common theme. Can you think of a figure from the real world who exhibits hubris? Who is this person? In what ways does he or she exhibit hubris?

2. Read one of Shakespeare’s plays. Take one of the scenes in which a number of characters are present and crucial to the effect of the scene. Now, in order to understand the importance of Aeschylus’s innovation of using more than one actor in a play, try to rewrite this scene for just one actor.

3. The concept of “biographical fiction’’ is important, especially when considering the lives of the ancients. Because little is known for certain about ancient figures, what we do know about them often comes in the form of stories based on some small, known fact about the figure. These stories, often false or fantastical, are called “biographical fiction,’’ and there are a good number of these stories floating around about Aeschylus. In order to understand how biographical fiction works, do a little research on a historical figure and then write a scene in which this figure interacts with his mother. Make sure to utilize some of the facts that you know about the figure.

4. Compare Homer’s representation of Agamemnon in the Iliad with Aeschylus’s representation in Agamemnon. What are some of the key differences? What are some of the key similarities?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Aeschylus. Persians. Edited by H. D. Broadhead.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1960. Aristotle. Nichomachean Ethics. Trans. Terence Irwin. Indianapolis: Hackett, 1999.

________. Poetics. Trans. Malcolm Heath. New York: Penguin, 1997.

Denniston, J. D., and D. L. Page, eds. Aeschyli Agamemnon. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1957.

Herington, John. Aeschylus. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1986.

Lebeck, Anne. The Oresteia: A Study in Language and Structure. Washington, D.C.: Center for Hellenic Studies, 1971.

McCall, Marsh H. Aeschylus. A Collection of Critical Essays. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 1972.

Murray, Gilbert. Aeschylus: The Creator of Tragedy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1940.

Otis, Brooks. Cosmos and Tragedy: An Essay on the Meaning of Aeschylus. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1981.

Rosenmeyer, Thomas G. The Art of Aeschylus. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1982.

Scott, William C. Musical Design in Aeschylean Theater. Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 1984.

Zimmermann, Bernhard. Greek Tragedy: An Introduction. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991.