World Literature

Elizabeth Barrett Browning

BORN: 1806, Durham, England

DIED: 1861, Florence, Italy

NATIONALITY: British

GENRE: Poetry

MAJOR WORKS:

Sonnets from the Portuguese (1850)

Aurora Leigh (1856)

Essays on the Greek Christian Poets and the English Poets (1863)

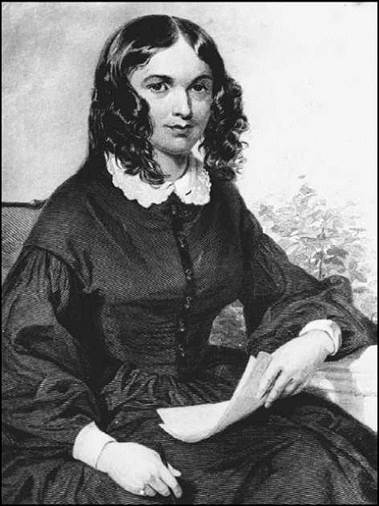

Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Hulton Archive / Getty Images

Overview

Elizabeth Barrett Browning is recognized as a powerful voice of social criticism, as well as an innovative poet whose experiments with rhyme and diction have influenced movements in poetry throughout the years. Although Barrett Browning is best remembered today for Sonnets from the Portuguese, a collection of love poems, she also wrote about social oppression with the same depth of emotion.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

A Large Family with a Domineering Father. Elizabeth Barrett was born on March 6, 1806, near Durham, England, to Edward Barrett Moulton-Barrett, a native of St. James, Jamaica, and Mary Graham-Clarke. The oldest of eleven surviving children of a wealthy and domineering father, she had eight brothers and two sisters. While forbidding his daughters to marry, her father nevertheless encouraged their scholarly pursuits. Her father was so proud of Elizabeth’s extraordinary ability in classical studies that he privately published her 1,462- line narrative The Battle of Marathon when she was fourteen.

An Accomplished Scholar and Writer, Despite Illness. In 1821, Barrett and her sisters began suffering from headaches, side pain, twitching muscles, and general discomfort. While her sisters recovered quickly, Barrett did not. She was treated for a spinal problem, though doctors could not diagnose her exact malady. Recent examination of Barrett’s symptoms has led to a hypothesis that she suffered from either tuberculosis of the spine or bronchial difficulties. Tuberculosis infected nearly seven in ten people in England in the early nineteenth century, before doctors understood how the disease was spread.

Even with her physical problems, Barrett continued to study and write, and she anonymously published An Essay on Mind, with Other Poems in 1826. The volume established what would become a theme in contemporary criticism—Barrett’s unusual, even ‘‘unwomanly,’’ scholarly knowledge. Barrett published Prometheus Bound: Translated from the Greek of Aeschylus, and Miscellaneous Poems in 1833, again anonymously, followed by The Seraphim, and Other Poems, the first book published under her own name, in 1838. The collection attracted much favorable attention.

During Barrett’s early years of publishing, she suffered two devastating losses: the unexpected death of her mother and the forced auction of her family home. Barrett’s father moved the family to London in 1835. At this time, Barrett was in such poor health that her physician recommended she live for a while in a warmer climate. Torquay, on the south coast of England, was selected, and she remained there for three years as an invalid as various members of her family took turns living with her and caring for her.

When she returned to the family’s London home, she felt that she had left her youth behind and that the future held little more than permanent infirmity and confinement to her bedroom. Despite her frail health, she was more fortunate in her circumstances than most female writers of her time. Thanks to inheritances from her grandmother and her uncle, she was the only one of the Barrett children who was independently wealthy. As the oldest daughter in a family without a mother, she normally would have been expected to spend much of her time supervising the domestic servants, but her weakness prevented her from leaving her room. Relieved of all household burdens and financial cares, she was free to devote herself to her intellectual and creative pursuits.

Literary Success and Marriage. Publication of her 1844 two-volume collection Poems established Barrett as one of the major poets of her day. The most important work of her life, however, turned out to be a single poem. Barrett admired the work of Robert Browning, a little- known poet six years her junior, and she expressed her appreciation of him in a poem of her own. Browning responded in a letter to Barrett, the first of 574 that they exchanged over the next twenty months. The letter began abruptly: ‘‘I love your verses with all my heart, dear Miss Barrett.’’ He continued, ‘‘I do, as I say, love these Books with all my heart—and I love you too.’’ Browning became a frequent visitor, not only inspiring Barrett’s poetry but also encouraging her to exercise outdoors to improve her health.

In September 1846, ignoring her history of poor health and her father’s disapproval, Barrett quietly married Browning. Her father never spoke to her again. The couple moved to Italy and settled in Florence in 1848, where their only child was born in March 1849. The birth of her son and the intellectually stimulating presence of her husband inspired a creative energy in Barrett Browning that she had never before experienced. She complained to her husband that, in comparison to his worldly experiences, she had lived like a blind poet.

Sonnets from the Portuguese. The courtship of Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning inspired Barrett Browning’s series of forty-four Petrarchan sonnets, recognized as one of the finest sonnet sequences in English. Written during their 1845-1846 correspondence, Sonnets from the Portuguese remained Barrett Browning’s secret until 1849, when she presented the collection to her husband. Despite his conviction that a writer’s private life should remain sealed from the public, he felt the quality of these works demanded publication. They appeared in Barrett Browning’s 1850 edition of Poems, her personal history thinly concealed by a title that implies the poems are translations.

Italian Politics. Barrett Browning’s subject matter became increasingly bold. ‘‘The Runaway Slave at Pilgrim’s Point,’’ a dramatic monologue, powerfully criticizes institutionalized slavery, showing herself to be in full sympathy with the abolitionist movement in the United States. Casa Guidi Windows (1851) records Barrett Browning’s reactions to the Italian struggle for unity. The unification of the various Italian states into one country in 1861 was the culmination of a movement known as the Risorgimento, which was made up of a series of regional revolutions and struggles in Italy. These were seen as a continuation of the American and French revolutions decades earlier. Barrett Browning was in sympathy with the Italian revolutionaries. The volume showed her increasing conviction that poetry should be actively involved in life and, perhaps more importantly, her confidence that a female poet should speak out about political and social issues. In this respect, Barrett Browning differed from such English writers as Jane Austen, Charlotte Bronte or Emily Bronte, all of whom seemed to avoid any mention of world politics in their novels.

Barrett Browning’s passionate engagement in Italian politics was also the subject of her 1860 collection, Poems before Congress. Barrett Browning criticizes political inaction that allows crimes against individual liberty. Furthermore, she focuses on a nation’s moral identity and asserts that it is a woman’s responsibility to be vocal about political issues. Instead of praising Barrett Browning’s combination of womanly feeling and manly thought, as notices of earlier works had done, reviewers of this volume complained that she had trespassed into masculine subjects.

Novelistic Experiment. Barrett Browning remained concerned about social issues in England during this period as well. Her Aurora Leigh (1856) is an ambitious novel in blank verse that embodies both Barrett Browning’s strengths and weaknesses as a writer. It bluntly argues that the topic of ambitious poetry should not be the remote chivalry of a distant past but the present day as experienced by ordinary people. Aurora Leigh achieves this goal of societal relevance, for it deals with an array of pressing Victorian social problems such as the exploitation of seamstresses, limited employment opportunities for women, sexual double standards, drunkenness, domestic violence, schisms between economic and social classes, and various plans for reform. Nothing stirred up more controversy than Barrett Browning’s candid treatment of the situation of the ‘‘fallen woman’’—a subject that was considered by the Victorian public to be outside the sight or understanding of a serious novelist or poet.

Barrett Browning fell ill with a sore throat and cold on June 20, 1861. A rupture of abscesses in her lungs proved fatal, and she died in her husband’s arms on June 29. In early 1862, Robert Browning published a final collection of his wife’s poetry as Last Poems, compiled from a list she had drawn up herself. Some of the twenty-eight poems were written prior to her marriage, some on recent political and personal events. Some of the pieces in Last Poems address the power imbalance in relationships between men and women. Reviews of this final volume sounded familiar inconsistencies: commending Barrett Browning for her purity and womanly nature while charging that her verse was coarse, irreverent, and infected by excessive anti-English political fervor.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Browning's famous contemporaries include:

George Sand (1804-1876): ''George Sand'' was the pen name of Aurore Dupin, a French feminist and novelist who lived an unconventional life.

Emily Dickinson (1830-1886): Most work by this famously reclusive American poet was discovered and published after her death.

Mary Russell Mitford (1787-1855): A close friend of Barrett Browning's, Mitford was an English novelist and playwright.

Giuseppe Mazzini (1805-1872): Mazzini, an Italian politician and revolutionary, advocated uniting the various states and kingdoms into one independent republic via a popular uprising.

Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807-1882): Garibaldi was an Italian soldier who was instrumental in bringing about a unified Italian republic.

Charles Fourier (1772-1837): This French philosopher created the word feminisme in 1837 and argued that women's rights were a logical extension of social progress.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Elizabeth Barrett Browning's work argued, in part, that women were as capable as men. Here are some other works that argue for equality between the sexes:

A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1791), a nonfiction work by Mary Wollstonecraft. This text argues that women should receive an education and similar rights to men.

The Woman in Her House (1881), a nonfiction work by Concepcion Arenal. In this book, the Spanish feminist argues that women should aim to be more than simply wives and mothers.

Story of an African Farm (1973), a novel by Mary Daly. The South African writer's first novel tells of three white children growing up in South Africa.

''Ain't I a Woman?'' (1851), by Sojourner Truth. This speech, given at the Ohio Women's Rights Convention by a political activist and former slave, argues against the myth of the delicate woman.

Works in Literary Context

Barrett Browning’s unorthodox rhyme and diction, once scorned, have been cited more recently as daring experiments. Kathryn Burlinson writes that ‘‘the half-rhymes, as well as the metrical irregularities, neologisms, compound- words, and lacunae that infuriated or disturbed her contemporaries now appear among the most interesting aspects of her work. [Virginia] Woolf’s claim that Barrett Browning had ‘some complicity in the development of modern poetry’ is an acute reminder that she influenced many later poets, not only the Pre-Raphaelites but 20th- century authors such as Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon.’’

Unconventional Sonnets. Sonnets from the Portuguese breaks with the conventions of the Elizabethan sonnet sequence—so closely associated with Dante Alighieri and William Shakespeare—by making the speaker a woman. Such poems were highly unusual in English literature during Barrett Browning’s time because they directly express female physical desire. The poems further challenge Petrarchan conventions by making marriage not the obstruction of love but its fulfillment. Margaret Reynolds commented, ‘‘This time, in the Sonnets from the Portuguese, the speaking subject is clearly a woman and a poet. Her beloved is in a different style too, he is also a poet and a speaking subject. By the end of the sequence of forty-four poems they are equal... she escapes an old regime where she was enjoined to silence or riddles, and she transforms herself into a speaking subject who can take her own story to market.’’

A New Kind of Fiction. This blank-verse poem, nearly eleven thousand lines longer than Milton’s Paradise Lost, constitutes a new genre, for it is simultaneously an epic and a drama. In a sense, Barrett Browning’s version of modern epic develops from Wordsworth’s own adaptation of the genre for his time; however, while he chose the poet’s autobiography as his subject, Barrett Browning contrived an ambitious fiction that is simultaneously an autobiography of an artist, a love story, and a poem of social protest. Novelist George Eliot said that she read Aurora Leigh at least three times and declared Barrett Browning ‘‘the first woman who has produced a work which exhibits all the peculiar powers without the negations of her sex.’’

Works in Critical Context

The critical view of Elizabeth Barrett Browning as a major poet—not to mention the greatest female poet of her time—persisted nearly to the end of the nineteenth century, when attention shifted to her life. Interest in her life then overshadowed the value of her work. As Barrett Browning became romanticized as a loving wife, her outspoken critique of her culture, her visionary social critique, and even her technical daring faded from the picture, leaving in its place a sentimental parody of both the work and the woman. Reconsideration of her poetry by feminist critics since the 1970s, however, increasingly values its modernity, specifically in its depiction of sexual politics and more broadly in its explanation of economic and political issues.

Sonnets from the Portuguese. When Sonnets from the Portuguese was first published, most critics ignored the work. It was not until a few years later, when the autobiographical nature of the poems became known, that the sonnets received widespread critical recognition. Response to the poems was glowingly favorable. Early commentators praised their sincerity and intensity; most agreed that no woman had ever written in such openly passionate tones. In addition, it was argued that the emotion of Barrett Browning’s verse was effectively balanced by the strict technical restraints of the sonnet form. Several critics compared the adept technique utilized in the sonnets to that of John Milton and Shakespeare.

By the turn of the century, critics became more cautious in their praise. Barrett Browning’s emotional expression was reevaluated in later years; what had been earlier defined as impassioned honesty was now considered overbearingly sentimental. Angela Leighton says, ‘‘Recent feminist critics ... tend to pass over these ideologically unfashionable poems. Somehow, their subject and their inspiration, which lack the larger sexual politics of Aurora Leigh, strike contemporary critics as naked and naive. They are, it is said with wearying regularity, simply too ‘sincere.’’’

On the other hand, some critics have stressed such technical merits of the sonnets as their structure and imagery and have expressed admiration for the cycle in its entirety. Jerome Mazzaro writes, ‘‘At times, in the Sonnets from the Portuguese, form and content are so deliberately left at odds to mark not excess but empty and artificial boundaries that periodically, on grounds independent of sincerity, critics . . . have called the competence of Barrett Browning’s verse technique into question.’’

Both as a revealing chronicle of a famous love story and as a technically skilled rendering of poetry’s most demanding form, Sonnets from the Portuguese endures as a testimony to Barrett Browning’s poetic skills. According to Reynolds, they are “accessible enough to be used by everyone, sentimental enough to be felt by us all. Since ... the so- called Browning love letters were published, the Brownings’ romance and Barrett Browning’s poems have become the true measure of romantic love.’’

Responses to Literature

1. Barret Browning’s sonnet ‘‘How Do I Love Thee?’’ is by far her most well known. Read the sonnet for yourself and think carefully about the poet’s choices throughout the poem. What do you think accounts for this poem’s enduring popularity?

2. Think about the writers, actors, and musicians that you like. How does knowing the details of their personal lives affect your experience of their art? In other words, do you get distracted by their personal life when reading, watching, or listening to their work?

3. Today, most people accept that men and women are equally intelligent. However, far fewer women than men pursue math and science careers, but girls tend to get higher grades than boys do. Using your library and the Internet, research the possible reasons for these unusual facts and then write a plan for ‘‘leveling the playing field.’’

4. Barret Browning was avidly interested in the unification of Italy, or the Risorgimento, that was under way while she lived in that country. An excellent novel set during this period is Giuseppe di Lampedusa’s The Leopard (1958), a huge best seller in Italy. The novel was made into an award-winning film of the same name in 1963.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Burlinson, Kathryn. ‘‘Elizabeth Barrett Browning.’’ Reference Guide to English Literature, 2d ed. London: St. James Press, 1991.

Leighton, Angela. ‘‘Stirring ‘a Dust of Figures:’ Elizabeth Barrett Browning and Love.’’ Critical Essays on Elizabeth Barrett Browning. New York: G. K. Hall & Co., 1999.

Periodicals

Mazzaro, Jerome. ‘‘Mapping Sublimity: Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Sonnets from the Portuguese.’’ Essays in Literature (Fall 1991): vol. 18, no. 2: 166.

Reynolds, Margaret. ‘‘Love's Measurement in Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s Sonnets from the Portuguese. Studies in Browning and His Circle (1993): vol. 21: 53-67.