World Literature

John Bunyan

BORN: 1628, Elstow, England

DIED: 1688, London, England

NATIONALITY: English

GENRE: Poetry, fiction, nonfiction

MAJOR WORKS:

Some Gospel-Truths Opened According to the Scriptures (1656)

A Few Sighs from Hell; or, The Groans of a Damned Soul (1658)

A New and Useful Concordance to the Holy Bible (1672)

The Pilgrim’s Progress from This World to That Which Is to Come (1678)

The Life and Death of Mr. Badman (1680)

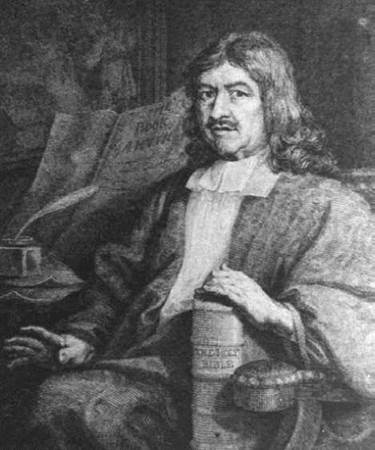

John Bunyan. Bunyan, John, painting. The Library of Congress.

Overview

The English author and Baptist preacher John Bunyan is recognized as a master of allegorical prose, and his art is often compared in conception and technique to that of John Milton and Edmund Spenser. Although he wrote nearly fifty works, he is chiefly remembered for The Pilgrim’s Progress from This World to That Which Is to Come (1678), which, translated into numerous foreign languages and dialects, has long endured as a classic in world literature. While structured from a particular religious point of view, The Pilgrim’s Progress has drawn both ecclesiastical and secular audiences of all ages and has enjoyed a worldwide exposure and popularity second only to the Bible.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

Humble Upbringing and Service in the English Civil War. John Bunyan was born in 1628 in Elstow, England, near Bedford, to Thomas Bunyan and his second wife, Margaret Bentley Bunyan. Not much is known about the details of Bunyan’s life; his autobiographical memoir, Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners (1666), is concerned with life events only as they relate to his own spiritual experience. His family was humble though not wholly impoverished, and after learning to read at a grammar school he became a tinker, a sort of wandering junkman, like his father.

The year 1644, when Bunyan was sixteen, proved shockingly eventful. Within a few months his mother and sister died, his father married for the third time, and Bunyan was drafted into the Parliamentary Army fighting against the Royalist cause in the English Civil War. The English Civil War occurred when conflicts between leaders of the English Parliament and the reigning monarch, Charles I, led to the execution of the king in 1649 and the institution of a commonwealth run by Parliamentarian and Puritan Oliver Cromwell. By 1660, however, Charles II—the heir to the English throne who had been living in exile—was brought back to England and restored as its ruler in an event known as the Restoration.

During the English Civil War, Bunyan did garrison duty for three years. He never saw combat, from which he seems to have thought himself providentially spared, because, as he reports, a soldier who was sent in his place to a siege was killed. Nothing more is known about Bunyan’s military service, but his exposure to Puritan ideas and preaching presumably dates from this time.

Conversion Experience. The central event in Bunyan’s life, as he describes it in Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners, was his religious conversion. This was both preceded and followed by extreme psychic torment. Under the influence of his first wife (whose name is not known) Bunyan began to read works of popular piety and to attend services regularly in Elstow Church. At this point he was still a member of the Church of England, in which he had been baptized.

One Sunday, however, while playing a game called ‘‘cat’’ on the village green, he was suddenly stopped by an inner voice that demanded, ‘‘Wilt thou leave thy sins and go to heaven, or have thy sins and go to hell?’’ Since Puritans were bitterly opposed to participation in Sunday sports, Bunyan saw the occasion of this intervention as no accident; his conduct thereafter was ‘‘Puritan’’ in two essential respects. First, he wrestled inwardly with guilt and self-doubt. Second, he based his religion upon the Bible rather than upon traditions or ceremonies.

For years afterward, he would hear specific scriptural texts in his head, some threatening damnation and others promising salvation. Suspended between the two, Bun- yan came close to despair, and his anxiety was reflected in physical as well as mental suffering. At last, he happened to overhear a group of old women, sitting in the sun, speak eloquently of their own abject unworthiness. This gave him the sudden realization that those who feel their guilt most deeply have been most chosen by God for special attention. Like St. Paul and like many other Puritans, he would proclaim himself the ‘‘chief of sinners’’ and thereby declare himself one of those destined for Heaven.

While he was never wholly free from inner conflict, Bunyan’s gaze from that point on was directed outward rather than inward, and he soon gained a considerable local reputation as a preacher and spiritual counselor. In 1653 he joined the Baptist congregation of John Gifford in Bedford. Gifford was a remarkable pastor who greatly assisted Bunyan’s progress toward spiritual stability and encouraged him to speak to the congregation. After Gifford’s death in 1655 Bunyan began to preach in public, and his sermons were so energetic that he gained the nickname ‘‘Bishop Bunyan.’’ Among Puritan sects, the Bedford Baptists were more moderate and peaceful in their attitude.

Imprisonment. Bunyan’s first published work, Some Gospel-Truths Opened (1656), was an attack on the Quakers for their reliance on inner light rather than on the strict interpretation of Scripture. Above all Bunyan’s theology asserted the helplessness of man unless assisted by the undeserved gift of divine grace. His inner experience and his theological position both encouraged a view of the self as the passive battleground of mighty forces, a fact which is of the first importance in considering the fictional narratives he went on to write.

Bunyan’s wife died in 1658 and left four children, including a daughter who had been born blind and whose welfare remained a constant worry. Bunyan remarried the following year. It is known that his second wife was named Elizabeth, that she bore two children, and that she spoke eloquently on his behalf when he was in prison. The imprisonment is the central event of his later career: It was at once a martyrdom that he seems to have sought and a liberation from outward concerns that inspired him to write literary works. Once the Stuart monarchy had been reestablished in 1660 under Charles II, it was illegal for anyone to preach who was not an ordained clergyman in the Church of England. Bunyan spent most of the next twelve years in Bedford Jail because he would not give up preaching, although the confinement was not difficult and he was out on parole on several occasions. In 1672, the political situation changed when Charles II issued a Declaration of Indulgence that allowed for greater religious freedom. Except for a six-month return to prison in 1677, Bunyan was relatively free to travel and preach, which he did with immense energy and good will. Bunyan’s principal fictional works were published during this post-imprisonment period and included the two parts of The Pilgrim’s Progress in 1678 and 1684, The Life and Death of Mr. Badman in 1680, and The Holy War in 1682.

Bunyan died in 1688 after catching cold while riding through a rainstorm on a journey to reconcile a quarreling family. He was buried at the Nonconformist cemetery of Bunhill Fields in London. By 1692 a folio edition of his works had been published, together with a biographical sketch that includes this portrait: ‘‘As for his person he was tall of stature, strong boned though not corpulent, somewhat of a ruddy face, with sparkling eyes, wearing his hair on his upper lip after the old British fashion; his hair reddish, but in his latter days time had sprinkled it with grey; his nose well set, but not declining or bending; and his mouth moderate large, his forehead something high, and his habit always plain and modest.’’

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Bunyan's famous contemporaries include:

John Owen (1616-1683): An influential Puritan theologian, he wrote condemnations of the state of the English Church and supported other radical religious thinkers, going so far as to bail Bunyan out of jail.

Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658): The preeminent military leader during the English Civil War, Cromwell went on to become head of state (called the ''Lord Protector'') after the execution of Charles I.

Charles II (1630-1685): King of England after the collapse of Cromwell's government, and monarch during the Restoration.

Samuel Pepys (1633-1703): English Parliamentarian and naval administrator best remembered today for his famous diary, which he kept from 1660 to 1669 and which covers events such as the Great Plague and Great Fire of London.

Works in Literary Context

Once Bunyan was able to preach freely, he infused his works with a sense of authority. He no longer prefaced them with apologies for his limitations, and he began to address his readers more in fatherly than brotherly fashion, as is clearly evidenced in his spiritual autobiography, Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners. When he was sent back to prison after the Declaration of Indulgence was withdrawn and the persecution of religious dissenters resumed, Bunyan began his first religious allegory, The Pilgrim’s Progress. Specific incidents in The Pilgrim’s Progress were borrowed directly from the Scriptures as well as from numerous secular and less edifying works available to Bunyan. But generations of critics have testified to Bunyan’s own comprehensive scope, rich characterization, and genuine spiritual torment and joy drawn from personal experience. Thus, autobiography and allegory serve as two main themes running through his major works.

Spiritual Autobiography. Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners, a relatively short narrative of about a hundred pages, stands unchallenged as the finest achievement in the Puritan genre of spiritual autobiography. Its origins lie in the personal testimony that each new member was required to present before being admitted to the Bedford congregation, and Bunyan’s allusions to St. Paul in the preface suggest that he intended the published work as a kind of modern-day Epistle for the encouragement of believers. Determined to tell his story exactly, Bunyan promises to ‘‘be plain and simple, and lay down the thing as it was.’’ What follows is a deeply moving account of inner torment, in which God and Satan vie for possession of the anguished sinner by causing particular Biblical texts to come into his head; Bunyan exclaims grimly, ‘‘Woe be to him against whom the Scriptures bend themselves.’’

Religious Allegory. The Pilgrim’s Progress records in allegorical form the author’s spiritual awakening and growth. An allegory is a story in which abstract ideas, such as Love or Hope, appear as concrete things or characters. The idea of human life as a pilgrimage was not new in Bunyan’s time; its story elements stretched back to even such adventurous journeys as The Odyssey., and its popularity was further intensified with the chivalric romances of the Middle Ages. For generations, the virtues and vices had been personified; those peopling the Christian’s difficult road to spiritual salvation—many who assist him when he is beset by obstacles and others who are the obstacles themselves—were familiar story elements to Bunyan’s first readers.

The Life and Death of Mr. Badman and The Holy War, while not as celebrated as Bunyan’s renowned allegory, are works equally representative of the author’s spiritual concerns, albeit from different perspectives. The first is a dialog between Mr. Wiseman, Bunyan’s fictional counterpart, and his faithful disciple, Attentive, who discuss the degeneracy of Mr. Badman as it progresses from youthful vices to misspent and miserable adulthood. The Holy War, like The Pilgrim’s Progress, is an allegorical depiction of spiritual struggle but, rather than employing the metaphor of quest or journey, it makes the human soul itself a bastion besieged by evil forces. The Holy War chronicles the original fall of humanity, the personal acceptance of salvation through Christ, the falling away after conversion, and ultimate restitution; on a more personal level, it also stresses the lifelong vigilance against sin that each person must wage.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

John Bunyan was neither the first nor the last author to use allegory to communicate his religious thoughts. Here are some other famous allegories:

Unto This Last (1860), an allegory by John Ruskin. A Victorian author, poet, and artist, Ruskin was also an influential religious thinker. In this work he lays down theories that would prove highly influential to left-wing Christian socialist thought.

The Divine Comedy (1308-1321), an epic poem by Dante Alighieri. Perhaps the best-known religious allegory, this fourteenth-century poem describes the author's journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven.

The Chronicles of Narnia (1949-1954), a series of novels by C. S. Lewis. Although these tales can be read simply as children's fantasy literature, Lewis purposely wove a deeper layer of Christian allegory into his stories as well.

Works in Critical Context

Generations of critics have testified to Bunyan’s own comprehensive scope, rich characterization, and genuine spiritual torment and joy drawn from personal experience. Charles Doe, one of Bunyan’s contemporaries, remarked: ‘‘What hath the devil, or his agents, gotten by putting our great gospel minister Bunyan, in prison? For in prison he wrote many excellent books, that have published to the world his great grace, and great truth, and great judgment, and great ingenuity; and to instance in one, the Pilgrim’s Progress, he hath suited to the life of a traveler so exactly and pleasantly, and to the life of a Christian, that this very book, besides the rest, hath done the superstitious sort of men more good than if he had been let alone at his meeting at Bedford, to preach the gospel to his own [audience].’’

The Pilgrim’s Progress. Although individual critical interpretations and appraisals of his writings have varied over time, the popularity and relevance of Bunyan’s work, most notably of The Pilgrim’s Progress, remain undiminished today. James Anthony Froude affirmed:

It has been the fashion to dwell on the disadvantages of his education, and to regret the carelessness of nature which brought into existence a man of genius in a tinker’s hut at Elstow. ... Circumstances, I should say, qualified Bunyan perfectly well for the work, which he had to do. ... He was born to be the Poet-apostle of the English middle classes, imperfectly educated like himself; and, being one of them-selves, he had the key of their thoughts and feelings in his own heart. ... [His] mental furniture was gathered at first hand from his conscience, his life, and his occupations. Thus, every idea which he received falling into a soil naturally fertile, sprouted up fresh, vigorous, and original.

Responses to Literature

1. What are Bunyan’s major themes? How does he express those themes through allegory?

2. In The Pilgrim’s Progress, Christian and Christiana are the allegorical stand-ins for Christian men and women, respectively. How do these two characters’ struggles differ, and what does that have to say about Bunyan’s views of men and women and their relationship to Christianity?

3. In your opinion, exactly how much progress does the pilgrim Christian make over the course of his journey? In what aspects does he evolve the most as a person?

4. How do you think Bunyan felt about the religious experience? Did he view it as an individual experience or a group experience? Research the Puritan movement and describe how Bunyan’s views fit into it.

5. What are Bunyan’s ‘‘stumbling blocks’’? What other allegorical obstacles to Christian virtue can you think of from other stories or legends?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Batson, E. Beatrice. John Bunyan: Allegory and Imagination. Totowa, N.J.: Barnes & Noble Books, 1984.

Brown, John. John Bunyan: His Life, Times, and Work, rev. Frank Mott Harrison. London: Marshall, Morgan & Scott, 1928.

Forrest, James F. John Bunyan: A Reference Guide, New York: G. K. Hall, 1982.

Furlong, Monica, Puritan’s Progress: A Study of John Bunyan. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1975.

Keeble, N. H., ed. John Bunyan, Conventicle and Parnassus: Tercentenary Essays. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1988.

Newey, Vincent, ed., The Pilgrim’s Progress: Critical and Historical Views. Liverpool, England: University of Liverpool Press, 1980.

Sutherland, James, Restoration Literature, 1660-1700: Dryden, Bunyan, and Pepys, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Watkins, Owen C., The Puritan Experience: Studies in Spiritual Autobiography. New York: Schocken, 1972.