World Literature

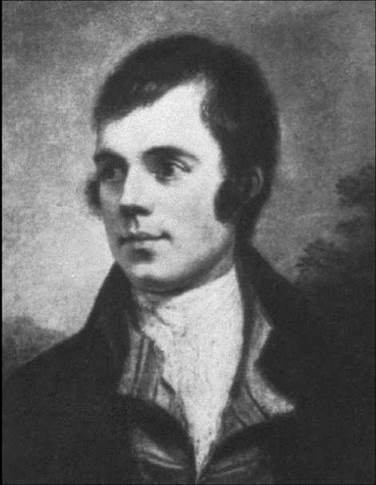

Robert Burns

BORN: 1759, Alloway, Ayrshire, Scotland

DIED: 1796, Dumfries, Scotland

NATIONALITY: Scottish

GENRE: Poetry

MAJOR WORKS:

‘‘Auld Lang Syne’’ (1788)

‘‘The Battle of Sherramuir’’ (1790)

‘‘Tam o’ Shanter’’ (1791)

‘‘A Red, Red Rose’’ (1794)

Robert Burns. Burns, Robert, photograph. AP Images.

Overview

Poet Robert Burns recorded and celebrated aspects of farm life, regional experience, traditional culture, class culture and distinctions, and religious practice and belief in such a way as to transcend the specific nature of his inspiration, becoming finally the national poet of Scotland. Although he did not set out to achieve that designation, he clearly and repeatedly expressed his wish to be called a Scotch bard, to extol his native land in poetry and song.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

Hard Work and Tragedy on Scottish Farms. Born in Alloway, Ayrshire, Scotland on January 25, 1759, to impoverished tenant farmers, Burns received little formal schooling, although his father, William Burnes (whose famous son later altered the spelling of the family name), sought to provide his sons with as much education as possible. He managed to employ a tutor for Robert and his brother Gilbert, and this, together with Burns’s extensive reading, furnished the poet with an adequate grounding in English education. Burns’s family moved from one rented farm to another during his childhood, enduring hard work and financial difficulties. As the family was too poor to afford modern farming implements, their hardships progressively worsened. All his efforts notwithstanding, William Burnes was forced to declare bankruptcy in 1783; his death followed soon afterward. Many biographers believe that watching his father slowly succumb to the ravages of incessant work and despair was a factor in Burns’s later condemnation of social injustice.

A Lover of Women and Poetry. While a young man, Burns acquired a reputation for charm and wit and began to indulge in romance. He once attributed the beginnings of his poetry to his sensuality: ‘‘There is certainly some connection between Love and Music and Poetry. ... I never had the least thought or inclination of turning poet till I once got heartily in love, and then rhyme and song were, in a manner, the spontaneous language of my heart.’’ Outspoken in matters religious as well as sexual, Burns was frequently involved in conflicts with the church, both for his relationships with women and for his criticism of church doctrine. Throughout his life, Burns was fervently opposed to the strict Calvinism that prevailed in the Scottish Church. The doctrine of these Calvinists included a rigid conception of predestination— the belief that the soul’s salvation was set at birth—and a belief in an arbitrarily chosen religious elite who were to attain salvation regardless of moral behavior. But although Burns was repelled by this, as well as by the Calvinist notion of humankind as innately and inevitably sinful, he was not irreligious; his theology has been summed up as a vague humanitarian deism, or belief in a distant and undefined God.

Short-Lived Fame. In 1786, Burns proposed to Jean Armour, who was pregnant with his child. Her parents forbade the match but demanded financial support from Burns. Angry at this rejection by the Armours and hurt by what he deemed Jane’s willingness to side with her parents, Burns resolved to sail to Jamaica to start a new life. The plan never materialized, however, for during that year his Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect was published in Kilmarnock. The volume catapulted Burns to sudden, remarkable, but short-lived, fame. Upon success of the book, he went to Edinburgh, where he was much admired by the local intellectual elite, though he afterward remained in relative obscurity for the rest of his life. In the meantime, he was still involved with Jean Armour, whom he was finally able to marry in 1788.

Back to the Hard Life. Burns carried on his dual professions of poet and tenant farmer until the next year when he obtained a post in the excise service. Most of Burns’s major poems, with the notable exception of ‘‘Tam o’ Shanter,’’ had been written by this point in his life. The latter part of his creative career was devoted to collecting and revising the vast body of existing Scottish folk songs. In 1796, at the age of thirty-seven, Burns died from rheumatic heart disease, apparently caused by excessive physical exertion and frequent undernourishment as a child.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Burns's famous contemporaries include:

Francisco Goya (1746-1828): The official painter for Spain's royal family, Goya's style straddled the classical and the modern. His use of color, his brush strokes, and his subversive subject matter would prove highly influential to later nineteenth-century painters.

John Dalton (1766-1844): English chemist and physicist, Dalton was the first modern scientist to propose a model of atomic theory.

Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832): An international celebrity in his own lifetime, Scott wrote several historical novels that were widely read and highly influential. His medieval epic Ivanhoe kicked off a craze of castle building among England's nobility.

George III (1730-1820): King of Great Britain and Ireland from 1760 to his death, George is best remembered today for being the king who lost the American colonies and for his ''madness'' that rendered him nonfunctional for the last decade of his reign.

Mungo Park (1771-1806): A Scottish explorer, Park gained widespread fame for his first journey to discover the source of the Niger River. Although unsuccessful, Park's solitary adventures in the African interior made him something of a celebrity. He returned for a second expedition with forty Europeans, all of whom, including Park, perished on the expedition.

Works in Literary Context

Through his treatment of such themes as the importance of freedom to the human spirit, the beauties of love and friendship, and the pleasures of the simple life, Burns achieved a universality that commentators believe is the single most important element in his work.

Freedom and Love. The topic of freedom—political, religious, personal, and sexual—dominates Burns’s poetry and songs. Burns’s innumerable love poems and songs are acknowledged to be touching expressions of the human experience of love in all its phases: the sexual love of ‘‘The Fornicator,’’ the emotion of ‘‘A Red, Red Rose,’’ and the happiness of a couple grown old together in ‘‘John Anderson, My Jo.’’

Vitality. Another frequently cited aspect of Burns’s poetry is its vitality. Whatever his subject, critics find in his verses a riotous celebration of life, an irrepressible joy in the fact of living. This vitality is often expressed through the humor prevalent in Burns’s work, from the bawdy humor of ‘‘The Jolly Beggars’’ and the broad farce of ‘‘Tam o’ Shanter’’ to the irreverent mockery of ‘‘The Twa Dogs’’ and the sharp satire of ‘‘Holy Willie’s Prayer.’’ Burns’s subjects and characters are invariably humble, their stories told against the background of the Scottish rural countryside. Although natural surroundings figure prominently in his work, Burns differed from Romantic poets in that he had little interest in nature itself, which in his poetry serves but to set the scene for human activity and emotion.

Scottish Nationalism. Burns’s deep interest in Scotland’s poetic heritage and folkloric tradition resulted in his amending or composing more than three hundred songs, for which he refused payment, maintaining that this labor was rendered in service to Scotland. Each written to an existing tune, the songs are mainly simple yet affecting lyrics of the common concerns of love and life. A great part of Burns’s continuing fame rests on such songs as ‘‘Green Grow the Rashes O’’ and, particularly, ‘‘Auld Lang Syne.’’

Works in Critical Context

Although his poetry is firmly set within the context of Scottish rural life, most critics agree that Burns transcended provincial boundaries. Edwin Muir commented: ‘‘His poetry embodied the obvious in its universal form, the obvious in its essence and truth.’’ This quality makes his work vulnerable to one charge often leveled against it—lack of imaginative subtlety. Some critics contend that Burns’s passionate directness renders him insensible to a more delicate expression of imagination; they find his poetry too accessible, too easily penetrated. A related objection is that Burns’s philosophical themes are trite, coming dangerously close to the sentimental and naive. Iain Crichton Smith carried the argument further, stating that Burns’s very universality weakens his stature as an individual poet: as Burns has no voice or philosophy that is uniquely his own, his poetry is ‘‘artless’’ in the negative sense of that word. The majority of critics, however, hold that Burns’s simplicity of theme is true to life—that his philosophy, while not profound, is true to itself and to human nature. It is widely admitted that Burns’s message is not primarily an intellectual one; rather, he expresses the familiar emotions and experiences of humanity. Critics agree that this talent rendered Burns particularly fit for his role as a lyricist.

‘‘The Cottar’s Saturday Night’’. Initial publication of Burns’s poems in 1786 was attended by immense popular acclaim, but eighteenth-century critics responded with more reserve. They eagerly embraced the romantic image of Burns as a rustic, untaught bard of natural genius—an image Burns himself shrewdly fostered—but some critics, particularly English critics, were somewhat patronizing. They found the Scots dialect quaint to a point but ultimately intrusive and distracting. Sentimental poems such as ‘‘The Cottar’s [or Cotter’s] Saturday Night’’ and ‘‘To a Mountain Daisy’’ received the most favorable attention; Burns’s earthier pieces, when not actually repressed, were tactfully ignored. ‘‘The Jolly Beggars,’’ for example, now considered one of Burns’s best poems, was rejected for years on the grounds that it was coarse and contained low subject matter. Although these assessments held sway until well into the nineteenth century, more recent critics have taken an opposing view. ‘‘The Cottar’s Saturday Night,’’ an idealized portrait of a poor but happy family, is today regarded as affectedly emotional and tritely moralizing.

‘‘To a Mountain Daisy’’. ‘‘To a Mountain Daisy,’’ ostensibly occasioned by the poet’s inadvertent destruction of a daisy with his plow, is now considered one of Burns’s weakest poems. Like ‘‘The Cottar’s Saturday Night,’’ it is sentimental and contains language and images that contemporary critics find mushy and false. ‘‘To a Mountain Daisy’’ is often compared with ‘‘To a Mouse,’’ as the situations described in the poems are similar; the latter is the poet’s address to a mouse he has disturbed with his plow. Most critics today believe that ‘‘To a Mouse’’ expresses a genuine emotion that the other poem lacks, and does so in more engaging language.

Interestingly, ‘‘To a Mountain Daisy’’ was written primarily in standard English, while ‘‘To a Mouse’’ is predominantly in Scots; critical reaction to these two poems neatly encapsulates the debate over whether Burns’s best work is in English or Scots. The issue remains unresolved, but on the whole, earlier critics preferred Burns’s English works, while recent critics have favored his Scots. Eighteenth-century commentators viewed Burns’s use of dialect as a regrettable idiosyncrasy, but modern critics contend that his English poems tend to degenerate into stilted neoclassical diction and overstated emotion.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Burns's use of the Scottish vernacular is one of the most distinctive aspects of his poetry. Other poets have used the same approach in their work:

Barrack-Room Ballads, a poetry collection by Rudyard Kipling. Like Burns, Kipling wrote poetry in a distinctive regional dialect of the British Isles, in this case the Cockney slang of the common British enlisted man.

Lyrics of a Lowly Life, a poetry collection by Paul Laurence Dunbar. Although most of his poems were written in conventional English, Dunbar, an African American poet, was one of the first to write poems in the dialect of Southern black culture, as in this 1896 collection.

The Works of D. H. Lawrence, a collection by D. H. Lawrence. Many of Lawrence's poems were written in the dialect of his native Nottinghamshire, what critic Ezra Pound called ''the low-life narrative.''

Songs of Jamaica, a poetry collection by Claude McKay. Published in 1912, these poems were the first published in McKay's native patois, an English-African hybrid language of the Caribbean islands. McKay would go on to be a major figure in the Harlem Renaissance of black writers and artists during the 1920s.

Responses to Literature

1. In his poem ‘‘A Red, Red Rose,’’ Burns uses several metaphors to describe his love for a woman. Do you think some of these metaphors are more effective than others? Give examples and explain your reasoning.

2. Why do you think Burns’s more melodramatic poems are the ones best remembered today?

3. Can you think of a modern form of poetry that uses a distinctive dialect? How does the use of dialect in poetry affect the reader? Do you think it enhances the poetry?

4. Burns uses a combination of English and Scottish dialect in ‘‘To a Mouse.’’ Why do you think he chose to combine the two? Why do you think certain passages were written in Scottish dialect?

5. After reading ‘‘To a Mouse,’’ write a poem of your own addressed to a small animal or insect that you often encounter but pay little attention to. Try to imagine how it would see you and how you would explain your life to it.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Angus-Butterworth, L. M. Robert Burns and the 18th-Century Revival of Scottish Vernacular Poetry. Aberdeen, U.K.: Aberdeen University Press, 1969.

Brown, Hilton. There Was a Lad: An Essay on Robert Burns. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1949.

Brown, Mary Ellen.Burns and Tradition. London: Macmillan, 1984.

Buchan, David. The Ballad and the Folk. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1972.

Carswell, Catherine. The Life ofRobert Burns. London: Chatto & Windus, 1930.