World Literature

Italo Calvino

BORN: 1923, Santiago de Las Vegas, Cuba

DIED: 1985, Siena, Italy

NATIONALITY: Italian

GENRE: Fiction, nonfiction

MAJOR WORKS:

The Path to the Nest of Spiders (1947)

Italian Folktales (1956)

Invisible Cities (1972)

If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler (1979)

Mr. Palomar (1983)

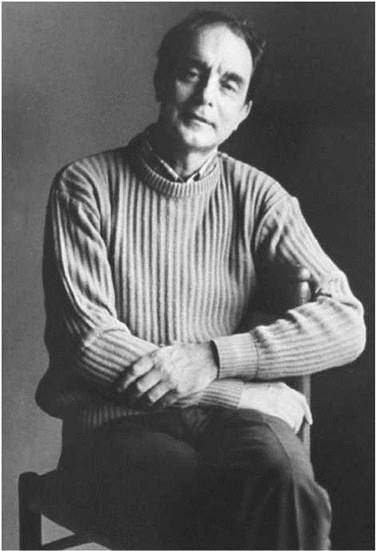

Italo Calvino. Calvino, Italo, photo by Elisabetta Catalano. The Library of Congress.

Overview

Italo Calvino was a noted journalist, essayist, and writer of fiction. Perhaps best remembered today for such literary works as Invisible Cities and the ‘‘Our Ancestors’’ trilogy, which blended fantasy, fable, and comedy to illuminate modern life, Calvino also made important contributions to the fields of folklore and literary criticism. Calvino’s growth as a writer paralleled the major literary trends of the last forty years; he moved from stories firmly grounded in reality to challenging story structures that simultaneously defied and redefined the traditional form of the novel. All the while, his writing remained accessible to the general reading public. More than two decades after his death, Italo Calvino’s writings remain both widely respected and crucially relevant to modern literature.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

The Child of Scientists. Italo Calvino was born in Cuba in 1923. His father, Mario, a botanist, was fortyeight when Calvino was born; his mother, formerly Eva Mameli, also a botanist, was thirty-seven. Shortly after his birth, his family returned to their native Italy. They raised Calvino on their farm in San Remo, where he would spend the better part of the next twenty years.

He attended public schools, and because his parents were nonreligious, he did not receive a religious education, nor was he subjected to the obligatory political indoctrination of fascist leader Benito Mussolini’s Italian government. A family tradition of devotion to science led him to enter the school of agriculture at the University of Turin, where his father was a distinguished professor of tropical agriculture.

War Stories and Political Tracts. Calvino’s studies were interrupted, however, when he received orders to join the Italian army. During World War II, Italy was a key member of the Axis powers, along with Germany and Japan; these countries fought against the Allied powers of England, France, and eventually the United States. Opposed to fighting for a cause he didn’t believe in, Calvino fled and joined the widespread resistance that was at that time fighting against Italian and German fascists in the country. During the two years that Germany occupied Italy (1943-1945), Calvino lived as a freedom fighter in the woods of the Maritime Alps, fighting both German and Italian fascists.

At the war’s end in 1945, Calvino joined the Communist Party, which supported the rights of workers and the collective sharing of both resources and wealth. He also returned to the University of Turin, this time enrolling in the faculty of letters. He graduated one year later with a thesis on British author Joseph Conrad. He also began writing for left-wing papers and journals.

Antonio Gramsci, the Marxist critic and cofounder of the Italian Communist Party whose writings were published posthumously in book form in the 1940s, exercised a remarkable influence on Calvino. Gramsci called for a national popular literature that would be accessible to the people and receptive to their real concerns. This new literature would be vibrant and rooted in social values and would cover a range of contemporary topics, including film, the American novel, music, and comic books.

Calvino began to record his war experiences in stories that eventually became his highly acclaimed first novel, The Path to the Nest of Spiders (1947). In this work he revealed the war as seen through the eyes of an innocent young soldier, the first of many youthful or naive protagonists he would use to reflect life’s complexity and tragedy. Considered a member of the school of neorealism—a literary movement that sought to bring a feeling of authentic real-life events and emotion into writing—Calvino was encouraged by such writer friends as Natalia Ginzburg and Cesare Pavese to write another novel in this tradition. These friends also invited him to join the staff of their new publishing house, Einaudi. He accepted and remained affiliated with Einaudi all his life.

Parisian Relocation. By the middle of the 1950s, Calvino was spending most of his time in Rome, the literary as well as political hub of Italian life. Tired of writing tracts for communist periodicals and, like many European intellectuals, disillusioned by the spread of dogmatic Stalinism—which shared many of the same ideals as communism, but in practice resulted in a murderous dictatorship—he resigned from the Communist Party. His disillusionment with Stalinist tyranny and perversion of communist ideals was sealed with the crushing of the Hungarian revolt in 1956 by forces of the Warsaw Pact. Indeed, as the years passed, Calvino became increasingly skeptical of politics in general.

In 1959, Calvino visited America for six months, and in the early 1960s, he moved to Paris. While living in Paris, he met Chichita Singer, an Argentinian woman who had been working for years as a translator for UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization). They were married in 1964. Also in the 1960s, Calvino joined the OuLiPo, or Ouvroir de Litterature Potentielle (Workshop of Potential Literature), an experimental workshop founded by Raymond Queneau. His association with this group would influence his subsequent work.

International Recognition and Honors. The 1970s saw the publication of three of Calvino’s most highly regarded novels: Invisible Cities, The Castle of Crossed Destinies, and If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler. During this period he and Chichita became the parents of a daughter whom they named Giovana.

After his move to Paris, Calvino’s work began to show a wider range of influences. A reconciliation with his father, which is treated in the short story ‘‘La strada di San Giovanni’’ (1990; translated in The Road to San Giovanni, 1993), gave him the freedom to explore and embrace a scientific perspective more vigorously, honing it into an attitude that blended humanist innocence and scientific wonder.

Calvino worked on the bookThe Castle of Crossed Destinies periodically for several years. In the 1973 postscript to The Castle of Crossed Destinies, Calvino writes about the double origin of the work. The idea first came to him in 1968 while he was attending an international seminar in which one of the participants spoke of fortune telling with cards. Publisher Franco Maria Ricci decided to bring out an art book employing the Visconti tarot cards illustrated by Bonifazio Bembo and asked Calvino to provide the commentary.

Calvino first won international recognition as a major writer with Invisible Cities, which some critics consider to be his most perfect work. The book has a carefully defined mathematical structure that displays its author’s abiding interest in symmetries and parallels. The book is ostensibly a conversation between Marco Polo and Kublai Khan, in which Polo enumerates the various cities of the Khan’s empire. Yet it can hardly be called fiction, for it does not resemble a narrative, nor does it tell a story.

Calvino’s readers had to wait six years for his next book, If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler (1979). As if to mockingly reassure his public of the authenticity of the book, he begins by stating, ‘‘You are about to begin reading Italo Calvino’s new novel, If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler. Relax ...’’ Described by Salman Rushdie as ‘‘the most outrageous fiction about fiction ever conceived,’’ the novel comprises the beginnings of ten other novels to emerge as a constantly mutating parody of literary genres.

Final Years. Calvino’s last novel was published after he returned to Rome. The protagonist in the novel Mr. Palomar (1985) is a visionary who quests after knowledge. Named for the telescope at Mount Palomar in Southern California, he is a wise and perceptive scanner of humanity’s foibles and mores. While the scheme of Mr. Palomar is less complex than that of Invisible Cities, Calvino again employs ideas borrowed from science, set theory, semiotics, linguistics, and structuralism.

In 1975, Calvino became an honorary member of the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters; in 1980, his Italian Folktales was included on the American Library Association’s Notable Booklist; in 1984, he was awarded an honorary degree by Mount Holyoke College; and in 1985, he was to have delivered the Norton Lectures at Harvard. However, Calvino died at age sixty-one on September 19, 1985, in Siena, Italy following a cerebral hemorrhage.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Calvino's famous contemporaries include:

Salvador Dali (1904-1989): A Spanish surrealist painter.

Pablo Neruda (1904-1973): Nobel Prize-winning Chilean poet also known for his outspoken communism.

Roland Barthes (1915-1980): French literary critic and philosopher.

Claude Levi-Strauss (1908- ): French anthropologist who developed the idea of structuralism as a method for understanding society.

Joseph Stalin (1878-1953): General secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1922 to his death in 1953; his brutal authoritarianism alienated many intellectuals affiliated with the Communist Party outside the Soviet Union.

Ernesto ''Che'' Guevara (1928-1967): Marxist revolutionary and guerrilla leader.

Works in Literary Context

Inspired by the legacies of such Italian luminaries as Renaissance poet Ludovico Ariosto and revolutionary scientist Galileo Galilei, Calvino interwove an ironic and allegorical use of fantasy with a profound interest in the phenomena of science and mathematics.

Neorealism. Calvino began his writing career in the mid-1940s, when neorealism was becoming the dominant literary movement. The dilemma for the young author coming of age at this time of cultural flux was whether to follow the accepted standard of social realism promoted by Marxist ideology or to move beyond literary convention on his own. For a while, Calvino was able to maintain a healthy balance and satisfy both his political commitment and evolving literary aspirations.

Folklore. During the 1950s, Calvino began to move away from neorealism. His ‘‘Our Ancestors’’ trilogy is markedly different from his earlier works. In The Cloven Viscount (1952), Calvino depicts a soldier halved by a cannonball during a crusade. His two halves return to play opposing roles in his native village. The Nonexistent Knight (1959) details the adventures of a suit of armor occupied by the will of a knight who is otherwise incorporeal. And The Baron in the Trees (1957) recounts the saga of a boy who, rebelling against the authority of his father, spends the rest of his life living in the branches of a forest. All three works, set in remote times, rely on fantasy, fable, and comedy to illuminate modern life.

Calvino frequently acknowledged that much of his fantastic material was indebted to traditional folklore. In 1956, he published his reworking of Italian fables, Italian Folktales, which has achieved an international reputation as a classic comparable to the work of the Brothers Grimm.

Science and Mathematics. Calvino continued to ‘‘search for new forms to suit realities ignored by most writers.’’ In the comic strip, he found the inspiration for both t zero (1967) and Cosmicomics (1968). In these pieces, which resemble science fiction, a blob-like being named Qfwfq, who variously exists as an atomic particle, a mollusk, and a dinosaur, narrates the astronomical origins of the cosmos as well as the development of the species over millennia. Calvino made further use of mathematics and logic in t zero, a collection of stories in which he fictionalized philosophical questions concerning genetics, cybernetics, and time.

Postmodernism. Much of Calvino’s later works are considered to be postmodernist, a sometimes vague and imprecise category. Postmodern literature relies on such techniques as the use of questionable narrators, fragmentation, and metafiction—the deliberate tweaking of narrative conventions. Postmodernist writers tend to reject the quest for finding order amid chaos that characterized earlier modernist works, instead often reveling in creating a sense of paradox or deconstructing the traditional narrative structure, as in Invisible Cities.

Influences and Legacy. Long an admirer of classical literature, Calvino’s earliest influences were drawn from the likes of fellow countrymen Dante and Ariosto, as well as Honore de Balzac, Miguel de Cervantes, and William Shakespeare. After his relocation to Paris, he built on this core of the Italian narrative tradition and classical studies, by looking to writers such as Vladimir Nabokov, James Joyce, and Robert Musil.

Italo Calvino continues to influence modern writers such as Aimee Bender and Amanda Filipacchi, both of whom explore similar fantastic, surreal, postmodern landscapes.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

In Invisible Cities, Calvino explores the emotional potential of imagining strange and distant lands, prompting readers to imagine their own world in new ways. Other works that allow readers a window into unusual worlds include:

Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of America during the Years 1799-1804 (c. 1814), a travelogue by Alexander von Humboldt. Brilliant German naturalist and explorer Humboldt records his observations of South America in this substantial work.

The Man Who Would Be King (1975), a film directed by John Huston. Based on a Rudyard Kipling short story, this adventure movie features Sean Connery and Michael Caine as former British soldiers who have a fantastic adventure in exotic lands not seen by Westerners in centuries.

On the Road (1957), a novel by Jack Kerouac. This classic of the Beat Generation chronicles a wild cross-country trip by fictionalized versions of Kerouac and his friends. Though it takes place in the United States of the 1950s, the landscape is both strange and familiar, much like the cities described by Calvino.

The Abyssinian (2000), a novel by Jean-Christophe Rufin. Rufin's debut novel tells of an adventurous doctor in seventeenth-century Cairo who, through a strange turn of events, is ordered on a dangerous diplomatic mission to the king of Abyssinia.

Works in Critical Context

Calvino’s essays on literature, collected in The Uses of Literature and Six Memos for the Next Millennium, clearly define his aesthetic criteria and philosophical temperament. In Six Memos, he states that his goal was to achieve a clarity and lightness of language that would allow him to conduct ‘‘a search for knowledge... extended to anthropology and ethnology and mythology ...a network of connections between the events, the people and the things of the world.’’

Calvino has long earned favor among literary critics. From his early works, Calvino’s narrative is highly personalized, exhibiting the enduring duality most critics find in his writing. Jay Schweig, on the other hand, has called Calvino’s later works “postmodernism at its most frustrating.’’

The Our Ancestors Trilogy. The three books that make up the Our Ancestors trilogy were widely praised when they were first published in the 1950s. Helene Cantarella, in the New York Times Book Review, calls the first book, The Cloven Viscount, ‘‘a dark-hued Gothic gem which transports us into the mysterious late medieval world of Altdorfer’s teeming battle scenes and Bosch’s hallucinating grotesques.’’ Gore Vidal has described the philosophical theme of The Cloven Viscount as a witty and refreshing parody of the Platonic Ideal. Regarding the final book, The Baron in the Trees, Frederic Morton, writing for the New York Times Book Review, states, ‘‘Mr. Calvino... seems to have intended nothing less than the deliberate transmutation of fantastic notion into universal allegory. Since he is not Cervantes he does not succeed—yet we are frequently entertained and even incidentally instructed.’’ Similarly, John Updike has claimed that Calvino’s novels ‘‘can no longer be called novels; they are displays of mental elegance, bound illuminations.’’

Responses to Literature

1. Italo Calvino’s collection of Italian folktales was a contribution on par with the works of the Brothers Grimm. Using Calvino’s work as a base, research and summarize five well-known Italian folktales.

2. The later works of Italo Calvino juxtapose fantastic narratives with rigorous applications of mathematical patterns. Note the appearance of numbers, patterns, sequences, and mathematics in general in such works as Invisible Cities, t zero, Cosmicomics, and If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler and explain their function.

3. As a young man, Italo Calvino was insulated from, and later revolted against, the rigid and dogmatic policies of Mussolini’s Italy. What was the state-approved art and literature of fascist Italy like? Can you compare fascist art to movements in art and literature that are popular today? Why do you think Calvino’s parents would have wanted to protect him from such influences?

4. Italo Calvino’s early writings are considered part of the Italian neorealist movement. What were the goals and objectives of this movement? Using your library and the Web, find out more about literary realism and neorealism. How do the two styles differ? How are they the same?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Adler, Sara Maria. Calvino: The Writer as Fablemaker. Potomac, Md.: Ediciones Jose Porrua Turanzas, 1979.

Contemporary Literary Criticism. Gale, Volume 5, 1976, Volume 8, 1978, Volume 11, 1979, Volume 22, 1982, Volume 33, 1984, Volume 39, 1986, Volume 73, Farmington Hills, Mich.: Gale, 1993.

Gatt-Rutter, John. Writers and Politics in Modern Italy. New York: Holmes & Meier, 1978.

‘‘Italo Calvino (1923-1985).’’ Short Story Criticism. Ed. Sheila Fitzgerald. vol. 3. Detroit: Gale Research, 1989.

Mandel, Siegfried, ed. Contemporary European Novelists. Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 1986.

Pacifici, Sergio. A Guide to Contemporary Italian Literature: From Futurism to Neorealism. Cleveland, Ohio: World, 1962.

Re, Lucia. Calvino and the Age of Neorealism: Fables of Estrangement. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1990.

Tamburri, Anthony Julian. A Semiotic of Re-reading: Italo Calvino’s ‘‘Snow Job.’’ New Haven, Conn.: Chancery Press, 1998.

Woodhouse, J. R. Italo Calvino: A Reappraisal and an Appreciation of the Trilogy. Hull, U.K.: University of Hull, 1968.

Periodicals

Newsweek, February 14, 1977; November 17, 1980; June 8, 1981; November 28, 1983; October 8, 1984; October 21, 1985.

New Yorker, February 24, 1975; April 18, 1977; February 23, 1981; August 3, 1981; September 10, 1984; October 28, 1985, pp. 25-27; November 18, 1985; May 30, 1994, p. 105.

New York Review of Books, November 21, 1968; January 29, 1970; May 30, 1974; May 12, 1977; June 25, 1981; December 6, 1984; November 21, 1985; October 8, 1987, p. 13; September 29, 1988, p. 74; July 14, 1994, p. 14.

New York Times Book Review, November 8, 1959; August 5, 1962; August 12, 1968; August 25, 1968; October 12, 1969; February 7, 1971; November 17, 1974; April 10, 1977; October 12, 1980; June 21, 1981; January 22, 1984, p. 8; October 7, 1984; March 20, 1988, pp. 1, 30; October 23, 1988, p. 7; October 10, 1993, p. 11; November 26, 1995, p. 16.

Times Literary Supplement, April 24, 1959; February 23, 1962; September 8, 1966; April 18, 1968; February 9, 1973; December 14, 1973; February 21, 1975; January 9, 1981; July 10, 1981; September 2, 1983; July 12, 1985; September 26, 1986; March 11, 1994, p. 29.