World Literature

Camilo Jose Cela

BORN: 1916, Iria Flavia, Padron, Galicia, Spain

DIED: 2002, Madrid, Spain

NATIONALITY: Spanish

GENRE: Drama, fiction, poetry

MAJOR WORKS:

The Family of Pascual Duarte (1942)

Journey to the Alcarria (1948)

The Hive (1951)

Secret Dictionary (1968)

San Camilo, 1936 (1969)

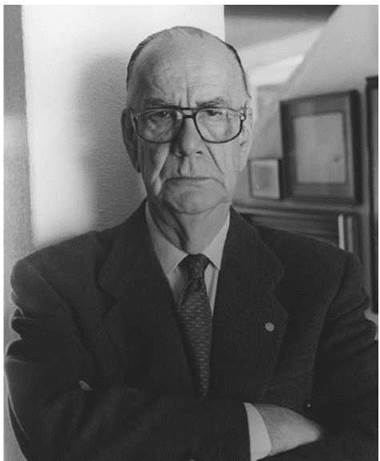

Camilo Jose Cela. Cela, Camilo Jose, photograph. © Jerry Bauer. Reproduced by permission.

Overview

A pivotal figure in twentieth-century Spanish literature, Camilo Jose Cela is best known for his stylistically diverse works of fiction that convey the social legacy of the Spanish Civil War. His first major novel, The Family of Pascual Duarte (1942), signaled the revival of Spain’s tradition of literary excellence, and Spanish culture’s gradual recovery from the civil war of 1936-1939. Throughout the repressive regime of General Francisco Franco, Cela suffered from governmental censorship. Nevertheless, he remained in Spain rather than going into exile and expressed himself audaciously in more than seventy works of literature, including essays, travelogues, short stories, dramas, and poetry. He won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1989.

Works in Biographical and Historical Context

Wounded in Civil War. Camilo Jose Manuel Juan Ramon Cela y Trulock was born in Iria Flavia (O Coruna), Spain, on May 11, 1916, to a Spanish father and English mother. His father worked as a customs official, and in 1933 the family moved permanently to Madrid. His eccentricities began to take root in his university years (1933-1936 and 1939-1943), during which he began and abandoned studies in philosophy, medicine, and law, without earning a degree. In 1934 a severe bout with tuberculosis changed his life. During his recovery, he read a seventy-one-volume collection of Spanish literature, fostering his literary aspirations.

Cela began writing poetry. His first collection was written in 1936, the first year of the Spanish Civil War, but not published until 1945. After war broke out in Spain, he was drafted into Franco’s Nationalist army, and wounded in battle. Franco defeated his antifascist opponents and established a dictatorship in April 1939. World War II started five months later.

Discharged from the military in 1939, Cela worked as a bullfighter, a painter, an actor, a civil servant in Franco’s government—and even, briefly, as a censor. From 1940, when he began to frequent the literary soirees at Madrid’s Cafe Gijon, the way was paved for the prolific output of his next six decades.

The Family of Pascual Duarte and Early Acclaim. Cela earned critical acclaim at age twenty-six with his first novel, The Family of Pascual Duarte. The novel relates, in the form of a memoir written to a friend, the life of a convicted murderer awaiting execution. Pascual responds to a life of poverty and frustration by killing his dog, his horse, his wife’s lover, and finally, his mother. He continually proclaims his repentance, but ultimately the reader must question Pascual’s sincerity and the cause of his murderous acts. Contradictions, gaps, and ambiguities plague the narrative.

The brutal atmosphere of this novel resonated with a nation recovering from a brutal conflict. Upon publication, however, its shocking and sordid details were condemned by censors and critics alike. Government censors, deeming Pascual Duarte the product of a depraved mind, seized the novel’s second edition in 1943 and held it for two years until it was again published in Spain. Since then, however, the book has gone through more than 250 editions, making it the second most widely read Spanish novel of all time, after Miguel de Cervantes’s Don Quixote.

Cela later called his second novel the antithesis of his first. Rest Home (1944) examines the private anguish of tuberculosis patients confined to a sanatorium; the work admittedly stems from the author’s firsthand experience with the illness. Even critics of Cela’s first novel praised this one for its sensitivity and lyricism. Rest Home illustrates Cela’s delight in structural symmetry: the novel is divided into two equal parts, each subdivided into seven chapters that correspond to the seven dying patient- narrators, six of whom are identified only by numbers.

Radical Nonconformity. Following the publication of his second novel, Cela entered a period of great productivity. He published a modern update of a famous sixteenth-century picaresque novel, New Adventures and Misfortunes of Lazarillo de Tormes (1944), and rapidly produced several collections of short stories. Journey to the Alcarria (1948) was the first of several collections of travel sketches recounting his vagabundajes (vagabond journeys) through the Iberian Peninsula. It won accolades for its atypical approach to the travel genre.

The Hive (1951) is generally considered Cela’s greatest work. It was first published in Argentina, because Spanish censors objected to its themes of depravity, hunger, and oppression. Set in Madrid in 1940, a time of severe wartime shortages, it is a social panorama chronicling three days in the lives of some three hundred characters who frequent a seedy cafe. Plunged midstream into the mundane conversations of Madrid’s teeming masses, one gets the impression of overhearing clandestine sexual encounters, illicit propositions, and other private matters, amid the nervousness of a society just getting used to a regime in which suspicious behavior or criticism of the new government warranted prosecution. A dead body turns up the first evening, and various incidents and bits of information begin to form story lines that might unravel the murder.

Cela’s works, starting with Pascual Duarte, confirm his radical nonconformity. The repression and censorship that became a way of life under Franco’s regime were catalysts for Cela’s artistic boldness and penchant for scandal. Cela intentionally fashioned the public persona of a literary outlaw, and his work continually pushed the boundaries of propriety. The novel Mrs. Caldwell Speaks to Her Son (1953) shocked the Spanish reading public with its taboo-driven theme. In two hundred short chapters, an elderly Englishwoman’s rambling letters to her dead son reveal her incestuous love for him.

Upholder of Obscenity. Cela was now a leading literary figure. He moved to the island of Majorca in 1956, and founded a journal, Papers from Son Armadans, which became a vital outlet for young anti-Franco writers. In 1957, he was inducted into the Royal Spanish Academy of Language. He befriended artists such as Joan Miro and Pablo Picasso; the latter contributed drawings to Cela’s Bundle of Loveless Fables (1962).

During the 1960s and 1970s, Cela furthered his iconoclastic departure from literary conventions and Catholic moral codes with works such as his Secret Dictionary (1968), a book of slang and obscene words, and Encyclopedia of Eroticism (1977). His innovative works, increasingly sexual and scatological, nevertheless received critical acclaim. As the Franco dictatorship waned, his topical essays began appearing in Spanish newspapers; these were later republished in numerous collections, into the 1990s.

Stylistic Experiments. His later novels were consistently experimental, starting with Eve, Feast, and Octave ofSt. Camillus’s Day 1936 in Madrid (1969; commonly called San Camilo, 1936). This work employs a hallucinatory, paragraph-free stream-of-consciousness narrative to examine the start of the Spanish Civil War. No capital letters appear in office of darkness 5 (1973); Christ versus Arizona (1988) consists of one single sentence, over a hundred pages long.

Two years after Franco’s death in 1975, Cela was appointed to the Spanish parliament by King Juan Carlos I. During the transition to democracy, he helped draft the Spanish constitution of 1978. He won several prestigious literary prizes in the 1980s and 1990s, culminating with the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1989. In his later years, his private life and scandalous behavior drew more attention than his writing, which continued at a prolific rate. He died in 2002, at the age of eighty-five.

LITERARY AND HISTORICAL CONTEMPORARIES

Cela's famous contemporaries include:

Alejo Carpentier (1904-1980): Cuban novelist and musicologist who was an early practitioner of magic realism.

Octavio Paz (1914-1998): Mexican poet and essayist; Nobel Prize winner (1990).

Albert Camus (1916-1960): French/Algerian existentialist novelist and philosopher.

Augusto Roa Bastos (1917-2006): Paraguayan novelist; author of the classic 'dictator novel,' I the Supreme.

Jose Saramago (1922- ): Portuguese writer known for his subversive political and religious perspectives; Nobel Prize winner (1988).

Joan Miro (1893-1983): Spanish painter whose surrealist works challenged bourgeois cultural norms.

Francisco Franco (1892-1975): Spanish dictator, 1936-1975.

Works in Literary Context

Camilo Jose Cela’s bold literary style is rooted in European realism of the nineteenth century, and especially in Spain’s Generation of 1898, who attacked the moral hypocrisy of Spanish society after the nation’s defeat in the Spanish-American War. The Family of Pascual Duarte was also inspired by the Spanish tradition of the picaresque— satirical adventure novels with roguish heroes, such as the sixteenth-century novella Lazarillo de Tormes. Critics also frequently compare Cela with American writer John Dos Passos; both wrote cinematic novels with shifting time sequences and a panoply of characters.

Tremendismo. Cela’s grotesque portrayal of illicit and repulsive aspects of Spanish society initiated a literary trend in Spain later called tremendismo. The term is vague, but it seems to denote a type of fiction that dwells on the darker side of life. For Cela, this emphasis on cruelty and graphic vulgarity, and subject matter that would customarily be off-limits for Spanish readers, reflects his commitment to defying Spain’s traditionalist, Catholic moral codes. This devotion to free expression led to censorship trouble and charges of indecency within Spain, but was an essential characteristic of his body of work, in fiction and nonfiction alike.

Patterns. Stylistic experimentation is a constant feature of Cela’s fiction. His later work features a decreasing emphasis on plot—the sequence of cause and effect is largely discarded—and an increasing emphasis on artificial patternings of events. The fragmented narrative of The Hive and the short micro-chapters of San Camilo, 1936 are examples. In his prologue to Mrs. Caldwell Speaks to Her Son, titled ‘‘A Few Words to Whoever Might Read This,’’ Cela speaks of the ‘‘clock novel... made of multiple wheels and tiny pieces which work together in harmony.’’ With this mechanical approach to constructing fiction, Cela imposes order upon what he perceives as a chaotic universe.

Spain’s Debt to Cela Cela has had an enormous impact on succeeding generations of Spanish writers. Much of the Spanish intelligentsia fled into exile as Franco came to power; Cela stayed and revived the nation’s literary tradition in a repressive era. At first, he collaborated with the regime, but later he served the cause of artistic freedom through his publication of Papers from Son Armadans and through his own literary provocations. The literature and art of contemporary, democratic Spain are indebted to the free expression Cela exercised.

COMMON HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Camilo Jose Cela's novel The Family of Pascual Duarte is a modern version of the picaresque, a genre incorporating social satire in an adventure format. The word picaresque comes from the Spanish word picaro (rogue); the protagonist of a picaresque novel is frequently a rascal, or denizen of the lower ranks of society. It is an enduring literary genre, as these titles from the contemporary era attest.

On the Road (1957), a novel by Jack Kerouac. The story of Sal Paradise and Dean Moriarty (Jack Kerouac and Neal Cassady) is the definitive work of the Beat generation and an influential piece of Americana.

Eva Luna (1985), a novel by Isabel Allende. This story of a poor orphan is both a romance and a portrait of a South American society undergoing revolution.

Harlot's Ghost (1992), a novel by Norman Mailer. A fourteen-hundred-page novel that sets one man's story against the early history of the Central Intelligence Agency.

Tipping the Velvet (1998), a novel by Sarah Waters. A young ''oyster girl'' falls for a music-hall male impersonator, and discovers her lesbianism, in this rollicking novel set in Victorian England.

Madonna from Russia (2005), a novel by Yuri Druzhnikov. In this recent novel by a respected emigre novelist, the character Lily Bourbon starts out as a Petrograd streetwalker, becomes a leading Soviet poet, then escapes to America.

Works in Critical Context

Despite the huge size of Camilo Jose Cela’s body of work, his reputation rests on his two most celebrated novels, The Family of Pascual Duarte and The Hive. Both faced censorship in Spain, yet achieved critical and commercial success—phenomenal success in the case of Pascual Duarte.

Many of his other works were popular with readers, including his travelogues and the novel Mazurka for Two Dead Men (1983), which won Spain’s National Prize.

Spanish Conservatism. The conservative nature of Spanish culture, which has persisted into the nation’s democratic era, affected critical reception to Cela at home. As Christopher Maurer wrote in the New Republic, ‘‘Cela has long been a household word in Spain, though not a polite one.’’ Beyond the issues of censorship, Spanish conservatives condemned Pascual Duarte and tremendismo as offensive to the nation’s moral sensibilities. A significant minority of critics continued to take offense to the rebellious and uninhibited nature of Cela’s voice. Outside Spain, critics tended to view tremendismo as a legitimate attempt to depict the corrupt and violent nature of life under fascist dictatorship.

Later Reception. Reaction to Cela’s later books was also varied. Their stylistic innovations, while praised by postmodern critics, made them less accessible to the general reader; meanwhile, their ever-escalating obscenity, and Cela’s controversial public behavior, led conservatives to declare him an embarrassment. Conservatives were not the only Spaniards unenthusiastic about Cela’s winning the Nobel Prize. Some political leftists never forgave Cela for his early support for Franco and his regime. His political commitments were somewhat ambiguous, but his allegiance to moral and artistic freedom was unstinting. Many non-Spaniards familiar with his work view it as almost an embodiment of Spain’s experience in the twentieth century.

Responses to Literature

1. Do some reading about the Spanish Civil War. Reflecting on Cela’s fiction, write about the different ways he presents the war’s impact on Spanish society.

2. Why do you think The Family of Pascual Duarte was banned in Spain? Conversely, why do you think its popularity has proven so enduring there?

3. Do you think Cela’s fascination with obscenity represents a simple pursuit of shock value, or does it have a larger purpose?

4. Some critics say that the main character of The Hive is the city of Madrid itself. Do you agree, and in what respect does the novel portray Madrid as a character?

5. What do Cela’s stylistic experiments, like the book-length sentence of Christ versus Arizona, contribute to the experience or meaning of his work?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books

Charlebois, Lucile C. Understanding Camilo Jose Cela. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1998.

Foster, William David. Forms of the Novel in the Work of Camilo Jose Cela. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 1967.

Kirsner, Robert. The Novels and Travels of Camilo Jose Cela. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1964.

Perez, Janet. Camilo Jose Cela Revisited. New York: Twayne, 2000.

Periodicals

Foster, David William. “Camilo Jose Cela: 1989 Nobel Prize in Literature.’’ World Literature Today 64 (Winter 1990): 5-8.

Ilie, Paul. ‘‘The Politics of Obscenity in San Camilo, 1936.’’ Anales de la novela de posguerra 1 (1976): 25-63.

Kronik, John. ‘‘Pascual’s Parole.’’ Review of Contemporary Fiction 4 (1984): 111-18.

Maurer, Christopher. ‘‘The Tremendist.’’ New Republic, September 3, 1990.

Miles, Valerie. ‘‘Camilo Jose Cela: The Art of Fiction CXLV.’’ Paris Review 139 (Summer 1996): 124-63.

Ugarte, Michael. ‘‘Cela Vie.’’ Nation, November 27, 1989.