Hacking Assessment: 10 Ways to Go Gradeless in a Traditional Grades School (2015)

HACK 7. TRACK PROGRESS TRANSPARENTLY

Discard your traditional grade book

To follow imperfect, uncertain, or corrupted traditions, in order to avoid erring in our own judgment, is but to exchange one danger for another.

— RICHARD WHATELY, ENGLISH ECONOMIST

THE PROBLEM: USING THE TRADITIONAL GRADE BOOK TO TRACK LEARNING

TRACKING LEARNING THE usual way won’t work if you throw out grades: What would you write in the grade book? What grade books do is provide a space to write down letters and numbers, both arbitrary and useless, and by the time they are averaged for the report card, they are outdated and meaningless.

· Averaging grades diminishes student learning to one number.

· Traditionally, the teacher does all of the tracking privately.

· Students only have access to their progress a few times a year when report cards are issued.

· There isn’t adequate space in a grade book to write down important anecdotal information.

THE HACK: TRACK STUDENT PROGRESS TRANSPARENTLY

By changing the way we track progress, we re-emphasize the partnership of learning between students and teachers. If we truly want to empower our students to be in charge of their own growth, then keeping notes about progress tucked away in a grade book that only a teacher sees seems counterproductive. There are many different ways to encourage tracking progress, but starting simply is usually the best way.

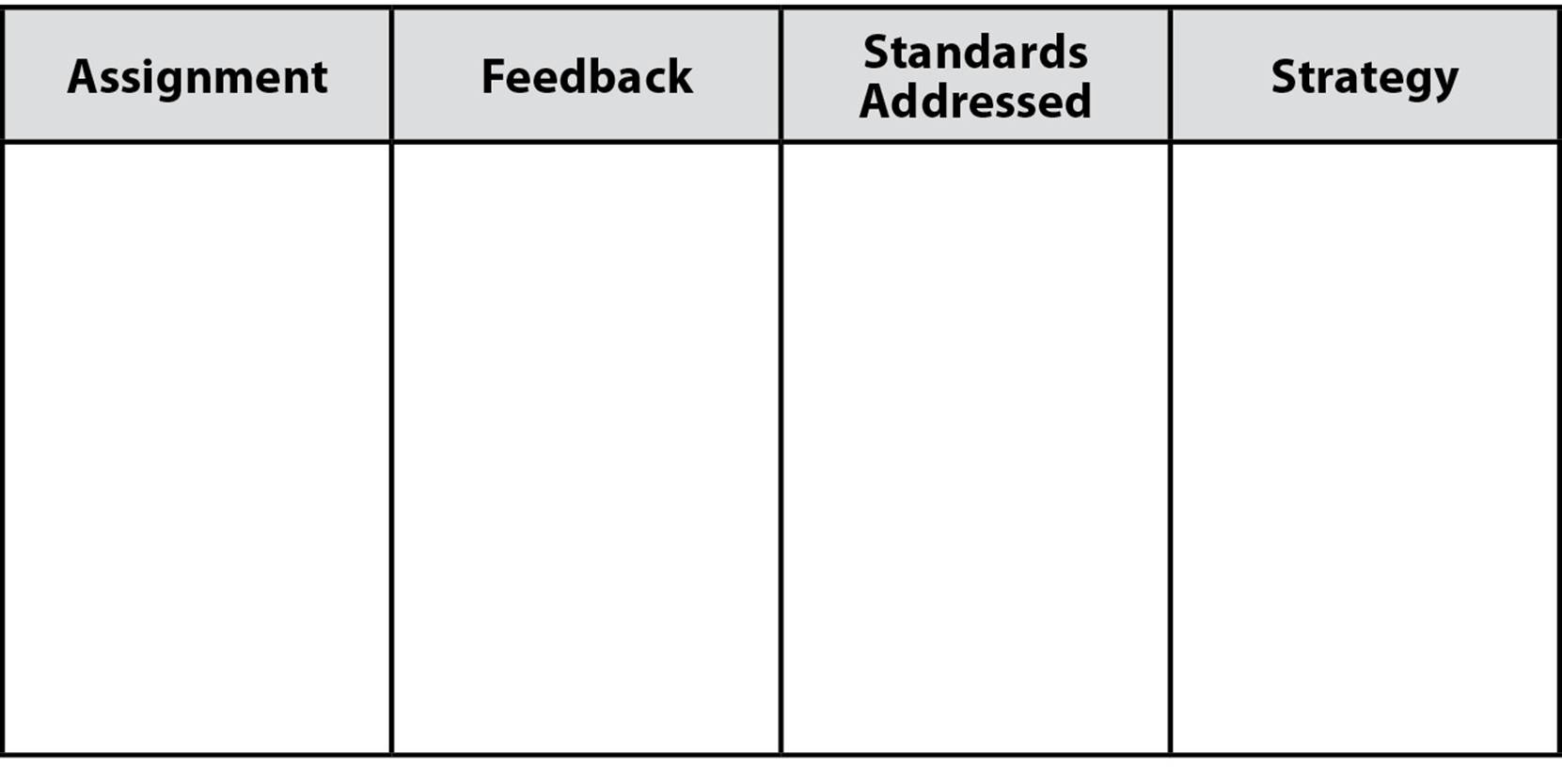

In a notebook, Google document, or spreadsheet, whichever the student prefers, ask students to generate a chart of four columns:

Column headers may vary depending on what you want your students to track, but this is a good start. Put students in charge of recording the feedback they receive. This may be written or verbal feedback that has been communicated one-on-one or in a small group. It will take time to establish a routine, but one way to help students is to allow them to record verbal feedback on their phones or take pictures of written feedback so it is stored for future reference.

Your old grade book is a waste of space and time. Don’t hesitate; just throw it out.

Eventually, students will be tracking all of the feedback they receive in class. When we put the power in their hands to record and remember, to work and improve, we relinquish the responsibility of tracking what every child needs all the time. This saves time and energy the teacher needs to help all students, and the person who most needs to know about a student’s progress—the student—does know. Students can keep the teacher informed as they progress.

WHAT YOU CAN DO TOMORROW

· Throw out your paper grade book. There is no need to keep it if students are taking on the responsibility for record keeping. As a matter of fact, your old grade book is a waste of space and time. Don’t hesitate; just throw it out.

· Make the purpose clear. Decide on the items that are appropriate for your students, depending on the content and the skills you want them to track.

· Determine the best record-keeping method for your class—with or without technology. Every learning environment is different, so you must select what will work best for you and your class, based on students’ ages, mastery levels, and access to technology.

· Conduct a test run. No matter what point it is in your school year, it’s important to immediately begin to develop a transparent system of tracking progress and feedback, even if it’s only a test run. Although it will be easier to completely overhaul record keeping in August or September, you can begin adapting your system in January or even after spring break. Limit the risk by experimenting with one unit and call it a “beta test,” in order to help “sell” it to students, parents, and administration.

A BLUEPRINT FOR FULL IMPLEMENTATION

It will take time to let go of the old and find the right system for your students. You may find that different students require different tracking methods, and as time goes on adjustment will be necessary. Exercise flexibility as you go.

Step 1: Generate two to three methods to share with your students to track their learning.

Create basic models to share with students based on their needs and the specifications of the unit. For example, if students are working on the scientific method, you’d want to have a different format for gathering feedback than if you were talking about solving math equations. Perhaps you have different T-charts or double-entry journal headings you want to use or maybe your visual learners need to track progress in a Venn diagram. Rather than letting them generate their own tracking methods at first, you may want to provide a selection of graphic organizers. As they become more proficient, encourage students to adjust their methods. This will be easier than allowing every child to create one of his or her own right away.

Step 2: Invite students to try a variety of methods to see which works best.

The first organizer may not work as well as the students or the teacher would like. Allow students the freedom to use a trial and error approach to finding the best tracking method. Since every child will have different needs, it’s a good idea to let each of them decide which method is the best fit. You may want to put students with similar needs in pairs or threes at first. Then they will be able to work together the same way they do with peer feedback.

Step 3: Check in with students to ensure they are using effective learning strategies.

It’s not enough to give students learning tools—teachers must follow up to see that the tools are being used. Put a procedure in place to ensure that students are using the learning strategies discussed in the feedback and adjusting them as needed. It’s a good idea to have students explain how they are implementing suggestions from the feedback when they write reflections about their process (see Hack 8). This way the teacher will be able to follow up with more specific feedback regarding how well the strategies are working.

Step 4: Teach students to set goals based on feedback.

After students receive feedback and track it, they should set new goals based on their progress. Using strategies the teacher provides and the specific standards that the work addresses, students should set a manageable number of goals (three to five) that can be tracked through the next assignment. Short-term goals work best for student tracking; the collection of shorter goals will establish a pattern and show growth for the year.

Step 5: Use the goals to establish appropriate strategies with students.

Based on the new goals, adjust the strategies appropriately, according to student need. What kinds of strategies have worked before? Can they be adjusted and re-used in this particular situation? Do new ones need to be employed?

Perhaps you taught students how to highlight and annotate their writing as a revision technique and it was successful. You might use the same strategy for a new challenge that addresses a different standard. Or maybe you abandon the highlighters and move to sticky notes, or introduce ways to pose questions in marginal annotations for the new challenge. Whatever the issue, the new goals should dictate the strategies.

Step 6: As goals are reached, teach students to develop new ones.

Since students are tracking their own progress, there should be a formal way of acknowledging success once a student reaches a goal. Then it’s time to develop a new goal based on the student’s current needs. Have students record when they achieved each goal using a checkmark or a date and write down the evidence that shows how they knew it was achieved so it is accessible later. From there, students can consider where they need more growth. If a student needs help with this step, it’s a good time for a conference to look at the work together.

OVERCOMING PUSHBACK

Students, in many cases, will be reluctant to take on more responsibility. Here are some issues people may raise and how to confront them.

If students can see their progress online, they will hyper-focus on feedback. While students have access to their learning progress via the online communication system, it doesn’t have to become the focal point of daily learning. The same students who would have been hyper-focused on grades may want to rush the process of improvement, but you’ll just need to have an open dialogue with these students about moving forward from wherever they are now.

Parents will have too many questions. Knowing this means we must be prepared with reasonable responses. Stick to the facts when talking to parents and use the work as talking points, but don’t allow parental bullying to force you to change your practice. Depending on the district you work in and the level of parent involvement, some parents may be used to getting their way. They may even go above your head and try to get administration to strong-arm you into changing your practice. Administrators who understand the shift will support you and should back you in these situations. Make sure there is a plan in place in case the situation escalates.

Administration will expect all teachers to do this. Why wouldn’t administration want all teachers to do something that is working for students? Some teachers may not want to change old practices because they are comfortable, but that doesn’t mean their way is the best way. Administrators should broach the suggestion to change when teachers have a sufficient amount of time to get used to the new system. They should provide training to ease anxiety about the change in the technology so fewer teachers will be uneasy about changing their practice.

THE HACK IN ACTION

The way we track learning should suit the students and the teacher. Here is one example of how high school teacher Adam Jones tracks student progress.

Teaching is an art form. It is a delightful dance of perspective-taking and feedback.

Paradoxically, the most impactful teaching is often invisible to the learner. The teacher exists in the background to listen attentively and offer feedback when necessary. When this is done effectively, students learn how to learn. Increasingly complex adaptive challenges help develop learner curiosity, passion and efficacy. As a teacher, you’ve succeeded when you walk into the classroom and you know the students no longer need you. Independence has to be the supreme goal.

The path to this end is rarely straight. It is a dance with each student to understand the starting point and investigate the role of feedback in the learning process. And that is why teaching is so dynamic, fluid, and fun. It is a chance to co-create a beautiful piece of art that, ultimately, the learner owns.

I love being a learner. Consistently exercising those muscles feels really important when taking the perspective of my students. I am in touch with what it means to be taught, and therefore I understand what I need to unlock my intrinsic motivation. For example, time to explore, examples to examine, opportunities to practice/fail, and access to the feedback of experts. Unsurprisingly, when I design a new class I am primarily focused on the perspective of the learner. These questions routinely come to mind:

· Would I be able to learn in this class?

· Would I be challenged, held accountable and discover a sense of ownership?

· What form(s) of ongoing feedback would most support my skill development?

· How could I effectively demonstrate that I’ve grown and developed a critical eye for the places I still need to grow?

Designing a class that adequately answers these questions and encourages learning is challenging. Never mind the more difficult challenge of actually tracking and making that learning visible. Detailed below is a description of what I’ve discovered are essential components of a class that encourages curiosity, passion and efficacy.

Accountability

In recent years, I have moved away from assigning numerical grades to my students’ work. Instead we focus on levels of proficiency (no information, advancing toward the goal, meeting goal, excelling past goal) when talking about their demonstration of learning. In addition to the marker of proficiency comes consistent and copious amounts of feedback. A numerical grade or a description of one’s level of proficiency means next to nothing without explanatory feedback.

At the start of the term, I create a master Google Spreadsheet that lists all of our assignments on the horizontal axis and our learning goals (Reading, Writing, Speaking, and Listening) and their subcategories on the vertical axis. Students make a copy of the document, share it with me, and we work together throughout the term to track their progress. Despite the simplicity of this system, it has assisted in keeping everyone aimed in the correct direction.

Additionally, students create Google Drive Digital Portfolios and share the folder with me. This cloud-based home serves as the visible headquarters for all their work—draft and final. I am eager to explore more integrated evidence-based learning information and tracking systems such as Chalkup and FreshGrade this year.

Feedback

Learning is all about feedback. Aside from setting the structure and expectations of the class, the most leverage for growth a teacher can consistently offer a learner is feedback. All assignments are opportunities to practice, receive feedback, and refine. I use the audio messaging app Voxer to maintain an open line of verbal feedback throughout the term. Whether I am providing verbal feedback on their speaking skills after a class-led discussion or summarizing, with particular emphasis, the narrative comments left on one of their Google Doc drafts, Voxer is an invaluable tool for personalization and relationship building.

I utilize the text messaging app Remind to send general announcements and after-class public praise to highlight examples of student learning. I regularly jump at the opportunity to use the formative assessment toolsSocrative and Kahoot, to check for understanding, provide feedback, and course correct. Additionally, all students in my class create content to be published on their blog which has the potential to provide an authentic audience ready to offer feedback in the comments section.

Self-Reflection

It is an essential component of enduring learning that students revisit their work and communicate insights from their progress. Creating scaffolding for students to experiment with this type of meta-thinking is critical for them to understand where they started, where they are presently, and what work is left to complete to reach their learning goals.

Students in my class complete a weekly (exit ticket) self-reflection Google Form. The information from this form serves as the mind-jogging catalyst for the midterm and end-of-term reflection interviews with me. These recorded conversations last between 10-20 minutes per student and typically take two days of class time. Additionally, I have been experimenting with the screencasting app Explain Everything as a self-reflection tool as an alternative to the more narrative approach with Google Forms.

The starting point for effective class design and teaching is one’s capacity to take the perspective of the learner and skillfully offer feedback. Further, if a transparent system of accountability is established; feedback is consistent, copious, and varied; and students develop a critical self-reflective eye, all the ingredients are present for learner independence to develop by way of curiosity, passion, and efficacy.

As we put kids in charge of their own learning, it is essential to remember that transparency is key. Teachers should no longer track the progress of students in isolation, adding marks for arbitrary things or recording homework completion. Nothing important fits in a grade book, so discard the grade book. Consider how you currently use your grade book and what might work more efficiently. Get kids involved in this process too; partner up to track the goals and progress of every child. Ask, “What can I do to make learning transparent?”

by STARR SACKSTEIN