Hacking Education: 10 Quick Fixes for Every School (2015)

HACK 4. TRACK RECORDS

Make Classroom Management Enduring and Real with a Simple Notebook

The content of your character is your choice. Day by day, what you choose, what you think and what you do is who you become.

—HERACLITUS, GREEK PHILOSOPHER

THE PROBLEM: MANAGING MINOR MISBEHAVIORS

CLASSROOM MANAGEMENT IS one of the most challenging aspects of teaching. If a teacher can’t get students to stay on task, treat each other civilly, follow basic instructions, and behave in a way that permits others to learn, there’s little else they can do. Forget about innovative teaching practices; if students are climbing the walls and throwing shoes at each other, all you can focus on is getting them to stop throwing those shoes.

Okay, so maybe they’re not throwing shoes. Maybe they’re just tardy. Or they forget to bring supplies. Their homework is incomplete, late, or missing. They’re whispering. Texting. Not following through. It’s these little things that create problems for you as a teacher. What’s worse, they will ultimately cause problems for the students. If students regularly make unproductive, disruptive, or careless choices, they are likely to struggle for the rest of their academic and professional careers, and they may never really understand why.

So what do you do about it? Many teachers use token or reward systems, or another kind of carrot, in an attempt to extrinsically motivate students to make good choices. Others are big proponents of the long lecture. Some teachers assign detention, take away privileges, and send kids to the office. Others just yell.

Regardless of the approach you take, one persistent question remains: Are we permanently changing behavior, or are students simply responding to punishments and rewards? Is there any way to teach students how to make good choices—both academic and non-academic—in a way that helps them internalize those habits? And can it be done without consuming tons of class time?

THE HACK: REPLACE PUNISHMENT AND REWARD WITH A TRACK RECORD

Instead of setting up a system of consequences for poor choices and rewards for good ones, let a student’s track record become the motivator: Using a basic notebook, allowing one page for each student, simply document any student behaviors that are noteworthy. If a student comes to class five minutes late, record that on his page along with the date. If a student does not turn in her homework, write that on her page.

Keep track of good choices too: If a student holds a door open for his peers to walk through, make a note of this. If someone else disagrees with a classmate during a discussion in a way that is respectful and productive, record it. The “Track Record” notebook is not just for documenting poor choices. It’s exactly what its name says: a track record—an accumulation of behaviors that constitute a person’s general reputation.

After an observation is recorded, you can share your documentation with that student privately. This could involve pulling her aside for a moment, giving her a peek at her page, and saying, “Thank you for staying focused during silent reading today. I added that to your track record.” Or, “Take a look at this. You’ve been tardy four times in the past week. What has changed? What’s going on?” If an incident doesn’t warrant an immediate conversation, you could set up a regular time (weekly, monthly, or once per marking period) to let students see their pages and discuss them with you.

This system is more reflective of what adults often refer to as the “real world,” where making bad choices doesn’t always result in immediately observable punishment. Adults who regularly interrupt others in conversation don’t get put in detention for talking out of turn. Their consequences are more subtle: When it comes time to invite people for an intimate dinner, the interrupter’s invitation may get lost in the mail. An employee who always arrives within a millisecond of her scheduled start time may not face disciplinary action, but she may be passed over when her boss is looking for someone to promote. By contrast, a driver with a spotless record who is pulled over for speeding is more likely to be let off with a warning than the person who has a glovebox full of parking violations. In all aspects of life, your track record—whether in writing or just stored in people’s memories—speaks to your character. The sooner students start to see the big picture on this, the better off they’ll be.

Using a Track Record to simply document student activity as it happens is a surprisingly effective way to encourage students to make better choices. Despite the fact that in most cases, the students receive no other consequence besides having their conduct recorded, many are bothered enough by having something negative written about them that they will naturally try to avoid it in the future. And the cumulative effect of multiple incidents being recorded together can be powerful: It’s one thing to complain that a student is talking too much, but it’s another matter entirely to tally the number of times you have to redirect that student back to her work and show her a grand total at the end of a class period. Or better yet, tell her you’re going to be taking the tallies, and watch how drastically those incidents are reduced.

The Track Record has other benefits: For one, it provides necessary evidence of ongoing problematic behavior in cases where a student needs to be referred for disciplinary action. Administrators like to know that you have done everything you could to solve smaller problems in your own classroom before sending students to the office. By documenting behavior in a Track Record, you have proof that the problem has been ongoing.

What’s more, recording positive behaviors can make well-behaved (and often ignored) students finally feel noticed, and it reinforces good choices in students who struggle with behavior. Adopting this practice will help you develop a more positive attitude toward a class that might, at first glance, appear to be out of control.

WHAT YOU CAN DO TOMORROW

Clearly, the value of a Track Record is its accumulation of observations over time, but you can start enjoying some of its benefits right away:

· Grab a notebook. As soon as you’ve gotten students started on a task that does not require your sustained involvement, pick up a notebook and open it to a fresh page. Draw a line right down the center. On the left side, begin recording observations of the positive behaviors you observe. On the right, record less desirable behaviors. For this first time, you can just keep the whole class on one chart. Tell students you’re just going to keep track of what happens today, because you want to make sure you’re noticing the good choices people are making as well as the problems.

· Write what you see. As you go about your normal routine, stop occasionally to jot down observations. If nothing noteworthy is happening, just write “Focused” and record the names of a few students who are really staying on task.

· Share your notes. If students ask what you are writing, feel free to share your notes with the individuals you are writing about, but if this detracts from class work too much, tell students you will discuss your notes with them at another time.

· Reflect. At the end of the day, look for patterns: Did you record more negative than positive behaviors? Did certain names appear more than once? This document can be used to set goals (such as “notice more positive behaviors”) and to plan brief conversations with key students the following day.

A BLUEPRINT FOR FULL IMPLEMENTATION

Step 1: Set up your Track Record.

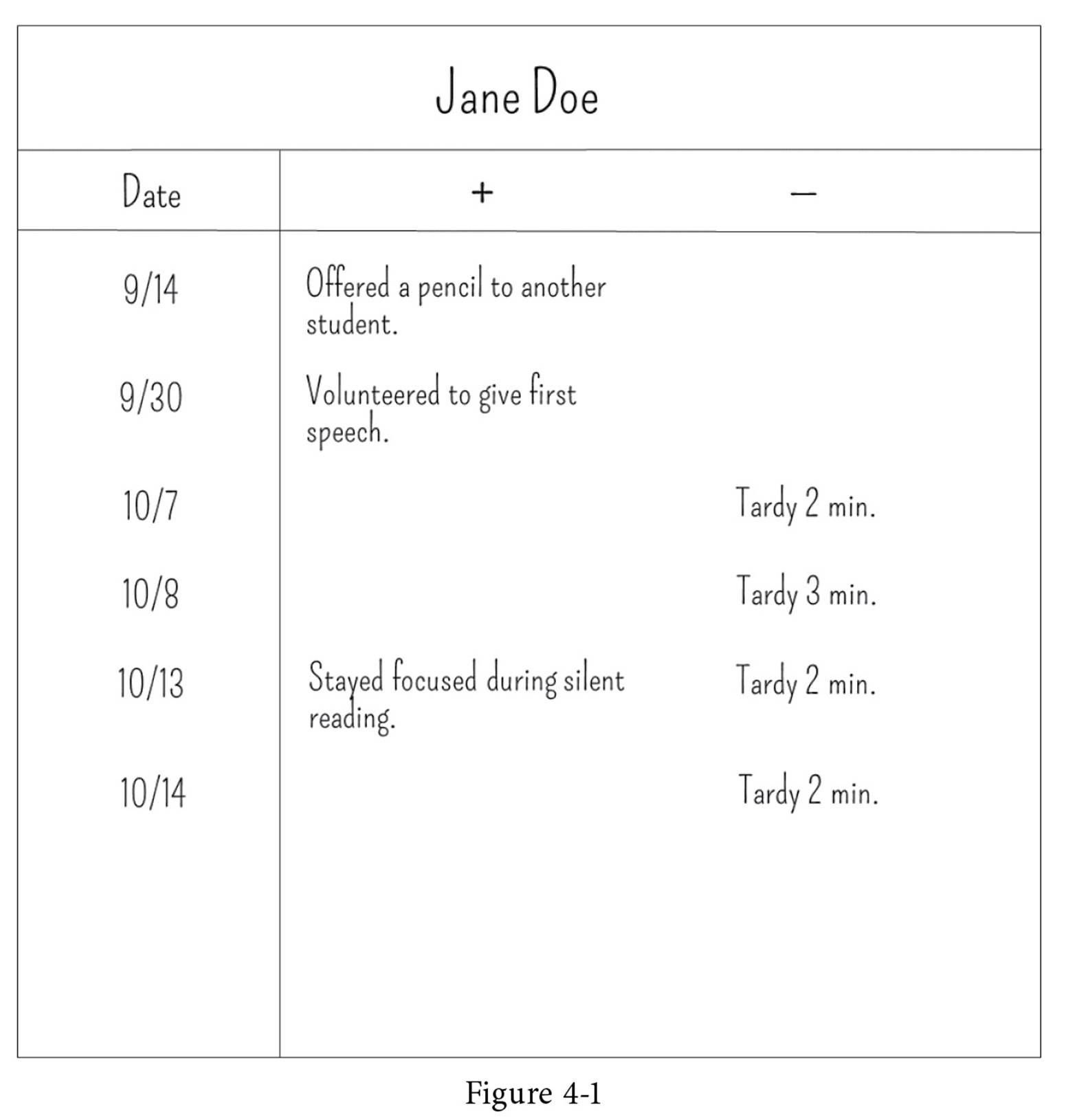

Create a system that will work best for you: Some teachers may prefer a full 3-ring binder, divided by class period if you are teaching the upper grades, where all students have their own page (like the one pictured in Figure 4.1). This system is nice for its symbolism: If students are accumulating a lot of negative incidents, you could have a talk with them about the patterns they have gotten into and then “wipe the slate clean” with a fresh, empty sheet, filing away the old one in a separate location. For other teachers, a table or chart may work better, where each student has his or her own row. One column in the chart would be reserved for positive behaviors (indicated by the plus symbol), and the other for poor choices (the minus symbol).

If plusses and minuses or the terms “positive” and “negative” don’t feel right to you, use whatever terminology or scale you like. You might choose to simply record observations without categorizing them as helpful or not. Just keep in mind that once you have recorded more than a few items, it will be more difficult to determine which choices were healthy, productive ones and which choices were not; having some kind of visual sorting system helps both you and the student recognize patterns right away.

Your Track Record can be kept on paper or in digital form, such as a Microsoft Word table, an Excel chart, or on a note-taking platform like Evernote—whatever works best for you.

Step 2: Choose your shortcut.

Whether you keep all your permanent notes in a binder or record them in an online document, quickly writing down events as they happen may require a more lightweight vehicle. This can be accomplished with a small notepad, a stack of post-it notes, a sheet of paper on a clipboard, or even your smartphone, where you can make shorthand notes to yourself, then transfer them to the Track Record later.

Step 3: Explain the system to students.

Doing this will make keeping the Track Record far more impactful than if students don’t know about it. Start by explaining how in many situations in life, we don’t receive small punishments or rewards for our behavior. Instead, we just develop a reputation, a track record that follows us wherever we go and influences how people judge us. You might even share the fable of the Boy Who Cried Wolf, in which a boy who played the same trick too often was not believed when he finally told the truth—his track record spoke for him.

Show students your record-keeping system—the chart or set of pages that have each of their names on them. Point out how the record is currently a blank slate —a “fresh start” that can be filled with positive or negative choices. Talk about the idea of a person’s character being the sum total of his or her choices, and how everyone makes mistakes, but a pattern of poor choices suggests bigger problems.

Step 4: Record behaviors in neutral, objective terms.

Because the purpose of this record is to illustrate how repeated behaviors cumulatively form a person’s general character, try not to add judgmental language when recording them. For example, instead of writing Disruptive in class today, which sounds like an opinion, write exactly what the student did: Drummed fingers on desk 8 different times in one hour. Similarly, for positive behaviors, instead of writing Helpful in group work, write Spent 20 minutes teaching Prezi to another student. Specific feedback, whether positive or negative, is far more instructive than general feedback.

Step 5: Be chill when documenting.

Calling a lot of attention to the act of recording a student’s behavior—positive or negative—can backfire. An embarrassed student may actually start behaving worse in order to save face, resulting in a game where the student does something, you write it down, then they do something else, wait for you to write it down, and so on. Don’t turn the Track Record into a sideshow. The point is to record observations without disrupting the flow of class, so make notes to yourself, then discuss them with the student later.

Step 6: Invite students to view their Track Records.

You might do this in regularly scheduled, brief conferences, or only on an as-needed basis. Use the Track Record as a tool for managing habits. For example, with a student who has recently developed a pattern of tardiness, show her the documentation, talk about the root cause of the lateness, and brainstorm some solutions. Then, to switch things up and change your focus to the positive, tell her you’re going to track how many times she arrives on time for the next few weeks.

Step 7: Allow for “fresh starts.”

If a student has accumulated a lot of negative documentation and wants a fresh start, let her have it. Replace crowded, blemished records with clean, blank ones and file the old ones away somewhere out of sight. This small gesture can be hugely symbolic to a student who is still figuring out who she is.

OVERCOMING PUSHBACK

I’m doing so many things already; I don’t have time to add one more record-keeping system! If this system is put into place with good intentions, it is likely to reduce behavior problems, which will ultimately give you more time for instruction and other classroom activities. Still, you can create shortcuts that will reduce the amount of time you spend recording.

One way to do this is to create codes for frequent behaviors. For example, if a student is five minutes late, you could simply record the date and the code 5T for “five minutes tardy.” Another way to save time is to use small post-it notes for your initial recording, then just stick them on the student’s page at the end of the day, allowing you to skip the step of rewriting them. You might even have students record their actions on the post-it notes themselves, then sign them, building in another level of accountability.

What if kids see each other’s pages? Privacy is an issue with all student records and documents, so treat your Track Record the same way you’d treat the rest of your private documents. If you are using a chart system rather than individual pages and want to show a student his or her record, simply zoom in the view on your computer screen so that only that student’s row is visible. If this is too difficult, consider resizing the chart cells to make this process easier.

This sounds too negative and nit-picky; I’m not interested in keeping track of every little mistake my students make. Fair enough. If you already have a classroom management system that effectively deals with negative behavior, then you don’t need this. Also, bear this in mind: You can record anything you want in this record. If you decide you only want to keep track of positive, constructive choices, you can do that. If you only want to record the most serious incidents rather than track many things every day, you can do that. What makes the Track Record different from other classroom management systems is that it is flexible.

What about really unacceptable behavior? I’m not going to walk away from a fistfight to write in a notebook! When faced with extreme or urgent misbehavior, handle it according to your school’s discipline guidelines. Call the office, or write a referral, whatever is required for serious incidents. The Track Record is meant to manage smaller infractions.

THE HACK IN ACTION

Jennifer Gonzalez: I used this system when I taught college freshmen and sophomores. Part of my role teaching introductory education courses was to recommend students for entry into the education major. For each student, I had to complete a form evaluating them on academic skills, ethical behavior, punctuality, and other qualities that were viewed as important contributors to success in teaching.

At the end of each semester, when it came time to complete these forms, I sometimes struggled. Over the term, I had formed a general opinion about each student’s habits and behaviors based on my experiences with them, but I hadn’t always kept track of those things. When making decisions that could impact their careers, I wanted something more substantial to back up my ratings.

In my third year I created a record-keeping system like the one described in this hack. Using a simple chart created in Microsoft Word similar to the one pictured in Figure 4-1, I recorded late arrivals, early departures (which turned out to be quite frequent for some students), late or incomplete assignments, excessive socializing at inappropriate times, and occasions when students demonstrated a lack of attention to written instructions or e-mail communication. I also recorded times when students showed great enthusiasm for a class activity, took initiative by contacting me in advance if they were going to miss class, offered an especially relevant comment in a discussion, or requested additional clarification on an assignment. Each of these behaviors contributed to success in school and in life but are not always quantified in a student’s grades.

When it came time to complete recommendation forms, I found these records to be incredibly useful in helping me make decisions about how to rate students. Later, when some of these same students came back to me requesting letters of recommendation for jobs, I was able to return to my chart and find specific examples of times when these students showed initiative or demonstrated the kinds of characteristics an employer would value.

The chart served another purpose as well: Because I told students about my system ahead of time, I found them to be more diligent about communicating with me than they had been in previous semesters. One student always seemed to have some kind of special event or activity causing her to miss class or to leave early, and I was able to pull up my record and show her that she had repeated similar requests multiple times over the semester. Seeing these incidents recorded one after another had an impact on her, and when I expressed concern that she didn’t seem committed to the course, there was evidence to support this opinion. Had I not set up a Track Record, my observations could easily come across as an unfair bias against her.

Sometimes the best solution to a complex problem is the simplest. If setting up a system of consequences and rewards, tokens and demerits isn’t a good fit for you, try the straightforward act of recording noteworthy incidents and showing your students that, ultimately, who we are really is the sum of the choices we make.