Secrets for Secondary School Teachers: How to Succeed in Your First Year (2004)

Chapter 6. Developing Plans for Instruction and Assessment

“What are we going to do today?” This is often the question that students ask as they come into the classroom. And it is usually followed by, “Will we be doing anything different?” or “Are we having a test today?”

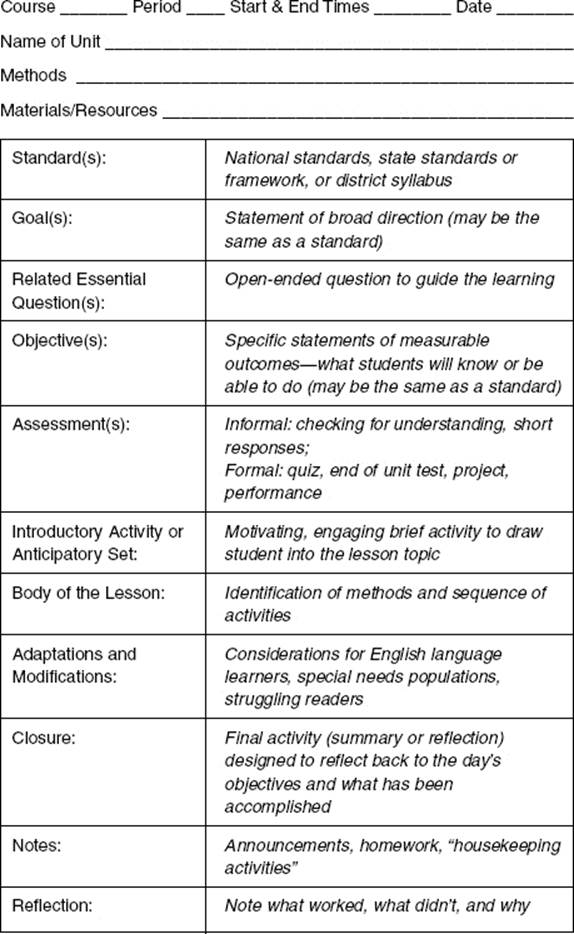

As the instructional leader in the classroom, you need to be ready. Once the students come in and the bell rings, the students’ eyes will be on you. It is the moment for you to take charge and commence the learning activities. A well-developed plan will be your guide. It will provide you with your selected objectives for the day, a sequence of activities, a list of needed resources, and assessments. While school districts or principals may request a particular format, there are common elements found in most lesson plans. A general daily lesson plan format follows in Figure 6.1 on page 61, after a short overview discussion on long-term and unit planning.

LONG-TERM PLANNING

Take a look at the entire curriculum for which you are responsible and do some preliminary curriculum mapping. This means look at the content standards and decide on the most appropriate sequencing of material. You will also want to estimate how much time will be needed for each topic or content area.

In your planning, note the dates of school vacations, standardized testing, school events, and final exams. This long-range planning gives you a global view of how you will proceed and points out the necessity of keeping a steady pace throughout the year. Most likely there will be adjustments to the plan along the way, but your initial outline will give you a good idea of how to proceed.

You may also be ready at this point to do a textbook correlation, that is, to identify which chapters or sections of chapters in your textbook match the standards. Or, you can examine the content of the textbook as you plan your units.

UNIT PLANNING

Now you are ready to break down the curriculum into units and go into more depth. Integrate concepts or skills together around a topic or theme. If you are using a textbook, you will see how the author or authors have chosen to do this by presenting material in chapter format. The teacher resource books and supplementary materials guides may even provide a number of scope and sequence charts for your consideration, based on the length of your semester. However, you do not have to follow this lead. You can pick and choose material from various chapters for a particular unit. You are not required to have the students tackle the text from “cover to cover.” (There is rarely enough time to do so.) Select the information that supports the content standards for your course. See what supplementary material, such as books or articles, will also support student learning.

Formulate Essential Questions

Today, many educators see the value of structuring learning based on questions. Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe suggest developing essential questions to engage students and guide their learning. The questions should reflect what you consider to be essential and enduring knowledge, reflect the heart of the discipline, and stimulate discussion. Questions should be open-ended and worded in a way that your students can understand them. By using essential questions, you help students make a personal connection to “the big picture.”

With the questions in mind, you can begin to identify the general types of learning experiences you want to provide, the resources you will need, and the best assessments to measure student achievement. For the day-by-day instruction, daily lesson plans are used.

DAILY LESSON PLANS AND ASSESSMENTS

Writing lesson plans serves several functions. The process helps you to organize your thinking about a course, in the short term, for a particular day or week, or in the long term, with a longer unit of study throughout the semester. Developing lesson plans also gives you the opportunity to consider the needs of the particular students in your course as you focus on their prior knowledge, abilities, cultural backgrounds, and levels of English language development in deciding how you will present new material and the forms of assessment you will use to determine if the objectives have been met. Having a set of lesson plans also has the benefit of giving you a sense of confidence as you start the day. It provides an agenda for you and your students to follow. And if the unexpected situation arises and you are not able to meet your class, such as a last-minute opportunity to attend a professional development activity, an unscheduled meeting, or you become ill, a prepared lesson plan will give the substitute a solid frame of reference.

Figure 6.1 Lesson Plan Format

Basic Information

Begin with the class reference information. Indicate the name of the course, the period, the date, the starting and ending times of the period, and the topic of study. Complete the sections on Methods and Materials/Resources after you have completed the rest of the lesson.

Select the Standard(s)

As most states have adopted content standards or state frameworks, the state standards will be your first reference point. There are also national standards developed for discipline areas that you can access as well. Your district may also have a curriculum in place that incorporates the state standards. These standards identify what students must know and be able to do. Districts may also have a set of benchmarks that identify timelines for meeting the objectives, which you will need to follow.

As the classroom teacher, you will have to do some preliminary inquiry with your students to determine whether they are ready to be introduced to grade-level standards. If not, you may have to incorporate activities based on lower level standards as a preview to the content you want to present.

Formulate Essential Questions

See section above under Unit Plans. If you have not done so earlier, you may want to develop essential questions at this point in your planning.

Goals

Some lesson plan formats include the identification of goals or statements of broad direction that facilitate the designing of curriculum. Goals use such terms as “understand,” “appreciate,” and “learn.” For example: “Students will appreciate the contributions of the impressionist painters.” “Students will understand Japanese poetry.” They are used for long-term, general planning.

Instructional Objectives

An instructional objective is a statement that defines the outcome or product of instruction in a way that can be measured and observed. It is a subset of a goal. For each content standard, you will need to identify one or more instructional objectives.

Whether you are writing for a daily lesson or a unit of study, the objectives will fall into three categories: cognitive or content; affective or feelings and attitudes; and psychomotor or skills. The emphasis will depend on the course. For example, keyboarding, physical education, band, and art will include many skill objectives; geography and economics will include more cognitive objectives.

In some cases, the objectives will follow a sequence such as in mathematics or language development; in other cases, they may follow a theme such as in social studies. Using Benjamin Bloom’s Taxonomy of Thinking Skills as a reference in content areas will ensure that you are including the high-level thinking skills of application, synthesis, and evaluation, as well as the basic skills of knowledge, comprehension, and application.

It is easiest to write objectives using sentences that begin with “The student will . . .” and follow with a verb that indicates performance, such as “define,” “identify,” “compare,” or “solve.” You will want to identify something that students can do that you can readily observe, so you can follow their progress. For example: “The student will describe the technique of the impressionist painters.” “The student will write a Japanese haiku.” Instructional objectives focus on what students will do.

At the start of each period, you can then share (orally and by posting on the board or an overhead) the day’s objective(s) with students. This not only allows students to know what is expected of them, but also helps them to measure their progress and prepare for tests or other forms of assessment.

Assessment

Now that you have written the objectives, the next step is to decide how you will determine the degree to which students have mastered the objectives. There are two categories of assessment: formative and summative.

Formative assessment takes place during instruction to see if students are progressing. Examples of formative assessment include checking for understanding by monitoring student work as it is completed in class or as homework. You may wish to ask questions as you present new material or demonstrate a new skill to make sure students comprehend what you are talking about or showing. Student responses might also be in the form of showing you answers on individual whiteboards, writing a summary at the end of a period for you to read, completing a graphic organizer that they submit for your review, or taking a quiz.

Summative assessment takes place at the end of a unit. Examples of summative assessment include a unit test or an alternative assessment such as a product (the “proof is in the pudding” in family and consumer sciences) or performance (debating a piece of legislation in government, or playing an instrument in band). You will not be able to use all the various types of assessments for any given unit, but over the course of a semester or year, you can offer students a variety of assessment experiences. Remember, the more different methods you employ, the more different opportunities you give the students to demonstrate their achievements.

Alignment

Assessments need to align with the standards and objectives. They should cover the skills, vocabulary, and content you present. Some teachers also include an item or two from previous units of learning to encourage students to keep reviewing past topics.

Students’ responses vary based on the type of assessment they are given. Some students do well on essay tests, but poorly on multiple choice. Since they vary in their ability to perform well on a given type of test item, you will want to provide multiple ways for them to show you what they have learned.

Written Tests

Written objective, “paper and pencil” tests include true/false, multiple choice, and matching items. Remember, while these types of tests are quick to administer and easy to score, they tend to cover basic information only and depend on students being able to read and comprehend English. They do not measure performance skills or show problem-solving skills.

Tips for creating written test items include the following:

• Using a 12-point font with a type face that is familiar to the students

• Printing on a solid background

• Including all relevant text and graphics on a single page

• Providing clear space for responses

• Listing multiple-choice items vertically

• Avoiding negative words such as “not” or “never”

• Emphasizing words that are significant, such as “never” or “always” by putting them in italics or boldface type

• When using fill-in-the-blank questions, placing blanks at the end of the sentence (“The capital of the United States is ______________.”)

• Selecting choice items that are the same length, shorter than the introductory stem, and include plausible answers

• Having only one right answer

• Using the same vocabulary as used during instruction

Make sure as much of your content as possible is included in the items. Students expect to be tested on all the content presented. If you use publisher-created tests, check to see that the above guidelines have been followed. Many schools have scantron forms available to score such tests electronically. This type of testing will also give students practice for standardized testing.

Fill-in-the-blank and open-ended, short-answer questions will take more time to grade, but will give you a fuller picture of what students know. They provide students with the opportunity to use their own words, identify examples, and give analogies. There may be a variety of correct responses to open-ended questions.

Special-needs students and English-language learners will need modifications of the test and adaptations of procedures in order to be successful on these types of items. Depending on their abilities, you may choose to provide word banks, select fewer items, and/or include samples of correctly answered items.

Essay questions are closely tied to students’ writing skills and ability to communicate. Therefore, they may be difficult for special-needs and English-language learners. Again, modifications and adaptation may be needed. Because it is more difficult to cover all the content with essay tests, many teachers use a combination of items. Grading essays takes a long time, but using rubrics (see page 68) will help you do so efficiently and reliably.

Alternative Assessments

By using alternative assessments (see Box 6.1), you allow students to give you a fuller picture of their achievement. Alternative assessments are also greatly appealing to students. They can involve a performance or demonstration, such as a dance; or a presentation, such as a PowerPoint slide show of a research project or a speech; or a product, such as a ceramic bowl, or a newspaper created by hand or by using Publisher software. Whatever the assignment, alternative assessments involve a lot of time and preparation to implement, and performances and presentations take time to evaluate.

BOX 6.1 LIST OF ALTERNATIVE ASSESSMENTS

Advertisement, artifact replicas, animated stories

Brochure

Collage, children’s book

Dance, debate, demonstration, diorama, drawings

Editorial

Fashion show

Games

Historical portrayal of person or event

Interview

Journal entry

K-W-L Chart

Letter, learning log

Maps, mobiles, models, movie, museum

Newscast

Obituary

Photographic essay, play, poem, political cartoon, poster

Questionnaire and results analysis, quilt

Role play

Simulation, slide show, song, speech, storyboard

Television program, think-aloud

Unit summary with illustrations

Video documentary, virtual field trip

Web site, word wall

Xylograph-wood engraving or other artistic rendering

Yearbook or similar type documentary

Z to A or A to Z alphabet-type presentation

Rubrics

Checklists, rating scales, or rubrics facilitate the evaluation process. By using rubrics or scoring guides with writing assignments, you identify the characteristics of a project or performance that will be graded and how the grade will be determined. Both students and parents appreciate such detailed information. The mystery is taken out of grading as it becomes more objective. Students can be involved in creating the rubrics and can self-evaluate their work based on what has been developed. Scoring can be holistic or analytic. You will also find that rubrics enable you to grade student work more quickly. In both types of rubrics, you would include the skills and knowledge pertinent to the unit.

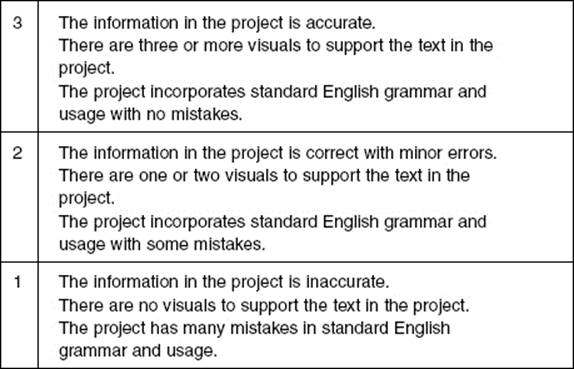

Holistic Scoring

A holistic rubric gives an overall picture by grouping together the characteristics being evaluated. A continuum of proficiency is developed from high to low and a point value assigned to each category. Figure 6.2 is a general example of a holistic scoring guide. A score is given according to the category that best matches the quality of the work. With such a guide, students know exactly what is expected. Teachers can quickly give feedback to the students, but it tends to be general rather than specific in nature.

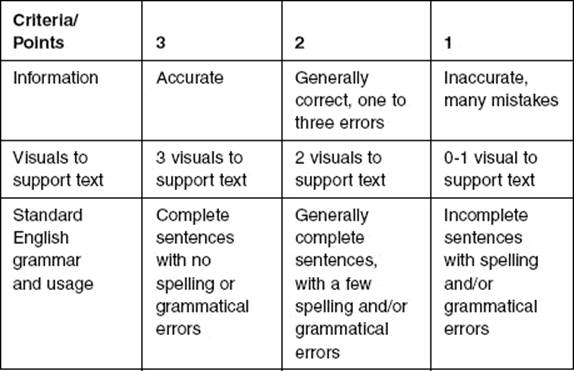

Analytic Scoring

Analytic scoring gives points for specific criteria. (See Figure 6.3.) It therefore gives more detailed feedback to the students. The criteria may or may not be grouped in categories. Points are totaled for a grade.

Introductory Activity

After your goals, essential questions, objectives, and assessments have been determined, you are ready to plan the lesson. Whether you have a traditional 45- to 55-minute period, or a block session that is longer, you will want to start with an introductory activity that is engaging and motivating. Effective introductions link to prior knowledge and stimulate the senses. You can use art, music, video, poetry, quotes, present an interesting question, or perform a brief demonstration. Movement is also important since children, much more than adults, get impatient with sitting still.

Figure 6.2 General Example of Holistic Scoring Guide

There are 3 points possible using this rubric. Additional criteria can be added to each level as desired.

Figure 6.3 General Example of Analytic Scoring Guide

There are 9 points possible using this guide. Other criteria to consider include organization, use of references, creativity, presentation, and neatness.

When I (Jeffrey) was teaching a lesson with Bushman children in Namibia, I quickly learned that anything we did together had to take place within a context of movement, whether that involved pantomime, dance, or exercise. My first thought was that in this so-called primitive culture, the children had never learned the skills of what it takes to be successful students. Then I realized that in our culture, we have actually unlearned the skills of what it takes to have fun while learning. The whole idea of learning by sitting motionless in seats while being talked to is antithetical to everything we know and understand about how learning takes places. The more active we can structure our lessons, the more likely that students will remain truly engaged.

Above all else, the introductory activity should be designed to capture student attention and set the stage for the day’s lessons. This opening activity is sometimes referred to as the “anticipatory set.” It should be followed with a statement of objectives and explanation of why this is important. Then you are ready to proceed.

Note: Many teachers begin the period with a “bellringer” or an initial “sponge” activity to get students involved as soon as the bell rings. This activity may or may not be related to the lesson of the day. A review “question of the day,” “warm-up” problem, or the copying of objectives and homework assignment, all of which are not related to the lesson and do not serve a motivating purpose, should not be considered as an introductory activity. We suggest listing these activities under the “Notes” section of the lesson plan.

Learning Activities

The body of the lesson follows. Now, you select the methods (for example, direct instruction, inquiry, or cooperative learning) and identify the corresponding activities for students, including time to practice what they have learned. Remember to consider learning styles as well as multiple intelligences in order to give students the opportunity to function in their areas of preference and strength, as well as to give exposure to and build confidence in their less-preferred and weaker areas. Some teachers try to estimate how much time each activity will take, structuring time for students to practice individually and in groups under their guidance. Include time for cleaning up material and supplies and putting books and resources away. Don’t forget to list the supplementary materials and supplies you will need in the “Materials/Resources” section of the lesson plan. With this list in hand, you will be able to gather quickly the items you need for the period. Some teachers like to list the Web sites they will access if using the Internet during class.

Adaptations and Modifications

Given the mix of students’ English language development, reading abilities, and cultural backgrounds, lessons need to be differentiated when and where it is possible to accommodate the various learners in the classroom. Moreover, reading strategies need to be incorporated into each class.

• Special-Needs Students. This population of students will have Individualized Education Plans (IEPs) indicating modifications and adaptations to be made for those who qualify. Some of the changes you may need to implement include the following: breaking assignments into small chunks, using graphic organizers, narrowing the focus to key terms and concepts, allowing extra time for completion of tasks, using a computer or other assistive technologies, having someone else write for them. Their assessments will have to be similarly modified. Each student will have an IEP, which will give you guidance.

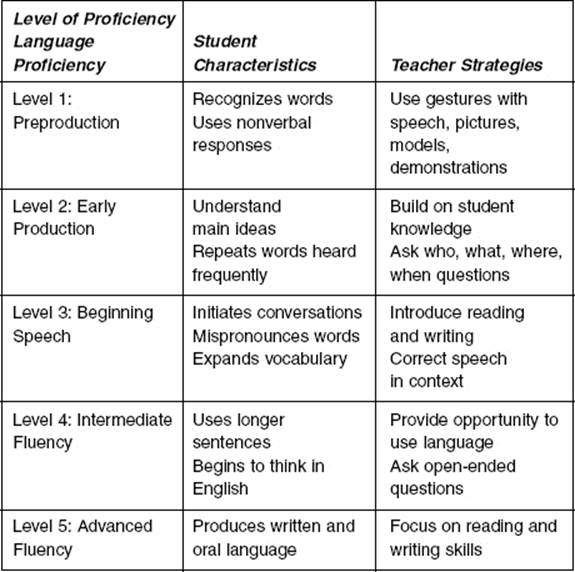

Figure 6.4 Brief Overview of Language Development Proficiency Levels and Student Characteristics With Corresponding Teacher Strategies

• English-Language Learners. These students present their own challenges. It may be helpful to look at the level of language ability and then design activities and assessments accordingly. A brief overview of five levels of language proficiency, characteristics of students, and a few corresponding suggested teacher strategies are found in Figure 6.4.

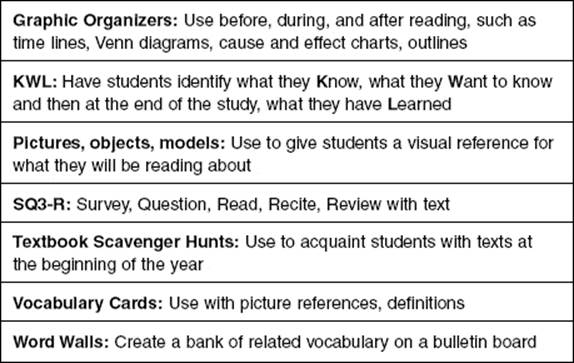

Figure 6.5 Literacy Strategies

The assessments for English-language learners will also require changes. You may decide to include a word bank and/or allow for drawings or other visual representations, outlines, or graphic organizers.

• Grouping. Some children enjoy working in groups, while others like to work alone. Different groupings should be facilitated. You may want to assign group members based on their diversity and learning needs or you may decide to have homogeneous groups and change group membership periodically so that all students have a chance to work with and get to know each other.

For some activities, the class may participate as a whole; for other activities, partner work may be most appropriate; and a third structure is to have students work individually. Or, you can use a combination with differentiated learning, that is, having students work on different tasks related to a given objective according to their abilities. This is an effective way of meeting the needs of all students in your class. In particular, it provides a structure for gifted students to work on challenging content at their own pace.

Teaching Reading

With the No Child Left Behind emphasis on literacy, all teachers need to be responsible for developing literacy skills. The literacy strategies listed in Figure 6.5 will help get you started.

Carefully selected supplementary reading material will often capture students’ attention and engage them on a given topic, where students often get lost in the monotony of textbooks.

Students often fail to see the practical value of what they are reading. I (Cary) remember thinking all the time, “What does this stuff have to do with anything?” or “Why will I ever need to know about this?” Well, my Government teacher had a unique solution to combat this problem. She had each of the students in her class get a subscription to Newsweek magazine. They offered a student rate so it wasn’t very expensive. Each week we were required to read the articles relating to American and world politics. We took a short quiz each Friday on how the articles related to the areas of government we were studying at the time. Not only was it more fun and interesting to read than the textbook, it also let us know what was going on in the world.

Closure

At the end of the period, take a few minutes to relate the learning activities back to the objectives. This can take place in the form of a brief summary (such as a whole-class, small-group, or partner discussion), or writing a reflection (such as a journal response in which students contemplate what they learned or experienced during the period), or a culminating activity that demonstrates mastery (such as integrating new vocabulary or performing a new skill).

Notes

At the beginning or at the end of the period, there may be various “housekeeping” activities you may want to list. Such items might include general school announcements and attendance at the beginning of the period, and directions for homework and other reminders related to your class at the end of the period.

Reflection

It is a good idea to spend some time reflecting each day after class to evaluate how the class went as compared to the plan. Some questions to ask yourself might include the following:

• How did the students respond to the introductory activity? Did they become engaged? Did it serve the inspirational or motivational purpose you intended?

• Were students able to progress successfully through the lesson? If not, what obstacles can you identify?

• How was the pacing? Too fast? Too slow? Just right?

• Were there any materials or references that should have been included?

• Were there any questions that the students asked that could have been addressed differently?

• Was the sequencing appropriate?

• Did students need additional scaffolding?

• What other changes would you make in the future? Is there anything you would do differently?

INTEGRATING INPUT FROM TESTING

At some point, and hopefully sooner rather than later, you will receive additional information on your students to help you with your planning. As the data from standardized testing become available, the results will be given to you. Criterion-referenced tests are designed to measure what students have learned against a set of standards (criteria) such as the district objectives. They are locally developed. The tests you give at the end of a semester, for example, will likely be criterion-referenced tests. Your district may have course exit exams. This type of test tells you whether or not your students have mastered identified objectives. You receive specific feedback from this kind of evaluation. You will see how well your students did in the past and whether any gaps exist that you will need to address. This information on your students will enable you to identify areas for re-teaching.

The other type of information you will receive is from the norm-referenced tests that are receiving much national attention. (They are being used as the basis for school accountability.) These tests measure students against like students, usually across the nation. For example, the achievement of a second-semester, 11th-grade student in your school is compared to all second-semester, 11th-grade students who took the test. You will receive information on how students did on various tasks included in the test; however, information from the task analysis tends to be general rather than specific. Also, these tests are highly dependent on reading ability, which can be a problem. Unfortunately, there is often a lag time of weeks or months between the date the test is submitted for scoring and the date the received results are shared with teachers.

FINAL THOUGHTS ON PLANNING

We encourage you to be as thorough as time permits in writing your initial lesson plans. For some activities, you will want to be very complete, perhaps even scripting what you want to say. For other activities, a brief outline will suffice. You may be able to follow a lesson plan from another source, such as the teacher’s resource kit for your textbook, a plan you received from another teacher, or one you found on the Internet. Sometimes you will be able to attach an already-developed lesson to the form you use; however, most likely you will have to make adjustments for your students. As time goes on, you will become more efficient in developing your plans.