SAT For Dummies

Part V

Where the Rubber Meets the Road: Practice Tests

Chapter 25

Practice Exam 3: Answers and Explanations

After you finish taking Practice Exam 3 in Chapter 24, spend some time checking your work by reading over the answers and explanations I provide in this chapter. Prop your eyelids open with toothpicks long enough to read every explanation — particularly for the questions you skipped or answered incorrectly but also for the questions you got right. You never know when I’ll include something that will help you increase your score on the real SAT! If you’re short on time, check out the abbreviated answer key I provide at the end of this chapter.

Note: To determine your score on this practice test, turn to the appendix.

Section 1: The Essay

This essay prompt asks you to think about ambition, effort, and goals. Is it better to aim high and risk falling flat on your face, or should you take a safer, surer shot? In horse-racing terms, should you bet your bank account on a long shot that might have a big payoff but also might put you in the poorhouse? Or should you select the favorite and limit your bet so you can’t win a fortune but can’t lose one either?

As always, you have 25 minutes to decide which position to take on this issue and to dig up some good historical, literary, or personal evidence to back up what you say. Here’s a sturdy outline that you can adapt to a variety of ideas:

![]() Introduction: State your thesis, quoting from Penn or Roosevelt if you wish. (You have two options: “Go for it!” or “Play it safe.”) Then plop in a couple of briefly stated supporting points. For example, in the go-for-it essay, you might explain how you took an honors course that no one thought you could handle, yet you succeeded. On the other hand, if you’re taking the play-it-safe position, you might write about the Greek myth of Icarus, a character who soared too close to the sun on wax wings, which melted, sending him plunging to his death. Two, maybe three, supporting examples are enough to get your point across to your audience.

Introduction: State your thesis, quoting from Penn or Roosevelt if you wish. (You have two options: “Go for it!” or “Play it safe.”) Then plop in a couple of briefly stated supporting points. For example, in the go-for-it essay, you might explain how you took an honors course that no one thought you could handle, yet you succeeded. On the other hand, if you’re taking the play-it-safe position, you might write about the Greek myth of Icarus, a character who soared too close to the sun on wax wings, which melted, sending him plunging to his death. Two, maybe three, supporting examples are enough to get your point across to your audience.

![]() Body paragraphs: Expand on the supporting points you briefly mentioned in the introduction — one in each paragraph. Be as specific as possible. Continuing with one of the examples from the preceding paragraph, if you’re explaining your success in a tough honors course, don’t just say that you studied hard. Explain how you left swimming practice every day at 4 p.m. and read your textbook under a plastic bag in the shower. Mention that you taped flash cards to the back of your sister’s head so you could study while she drove you to school. You get the idea: Provide plenty of details.

Body paragraphs: Expand on the supporting points you briefly mentioned in the introduction — one in each paragraph. Be as specific as possible. Continuing with one of the examples from the preceding paragraph, if you’re explaining your success in a tough honors course, don’t just say that you studied hard. Explain how you left swimming practice every day at 4 p.m. and read your textbook under a plastic bag in the shower. Mention that you taped flash cards to the back of your sister’s head so you could study while she drove you to school. You get the idea: Provide plenty of details.

![]() Conclusion: Here’s where you very slightly stretch the ideas you’ve covered thus far. In the play-it-safe essay, you may conclude that realistic, practical goals accomplish more for the world and society than flashier, reach-for-the-moon aspirations. In the go-for-it version, you may consider the world without daring visionaries; perhaps the human race would still be living in caves.

Conclusion: Here’s where you very slightly stretch the ideas you’ve covered thus far. In the play-it-safe essay, you may conclude that realistic, practical goals accomplish more for the world and society than flashier, reach-for-the-moon aspirations. In the go-for-it version, you may consider the world without daring visionaries; perhaps the human race would still be living in caves.

After you have a good idea of what a solid outline looks like for the ambition debate addressed in Practice Exam 3’s essay prompt, it’s time to score your own essay. Before you get started, turn to Chapter 8 and read the samples there. Then score your essay using the scoring rubric in Chapter 7; be honest with yourself as you determine how your essay measures up to the rubric.

Section 2: Critical Reading

1. E. The key word in this sentence is because, which tells you that you’re looking for cause and effect. The sentence reveals that Woody has established a pattern: always filming movies in New York City. What happens when someone breaks a pattern? Everyone is surprised — also known as Choice (E).

2. C. Go through the word pairs in order. The celebrity is shy, so if the fans believed she was outgoing (the opposite of shy), the verb you insert in the first blank must have an element of surprise in it. Amused doesn’t fill the bill, so Choice (A) is wrong. Choice (B) has the opposite problem. The verb amazed expresses extreme surprise, but diffident is a synonym for shy. Choices (D) and (E) make no sense. Why would fans be antagonized (irritated) or appalled (disgusted) by a celebrity who’s talented or celebrated? Choice (C), on the other hand, is a perfect match. The celebrity was smiling, which reassured worried fans who imagined that their star was depressed.

3. A. The sentence tells you that the resort’s advertisements hit both mega-millionaires and people who have to count every penny. That’s a broad range, making (A) the answer you’re looking for. The only other possibility is (C) because a good ad campaign is, by definition, effective.However, Choice (A) fits the sentence more specifically because it takes into account the wide span between the wealthy and those of limited means.

4. D. Think you’re on a lunch break? Think again, according to the sentence. Your boss can get you even as you munch on a double cheeseburger. Real-life experience helps here because I bet you see a phone call from the boss as a kind of tyranny, not divisiveness (causing separation), insignificance (unimportance), versatility (having many uses), or proliferation (expansion).

5. B. The subject is complex, and generalizations simplify. Hence, you need a verb that condemns generalizations. Okay, Choices (B) and (E) fill that bill because rejected means “not accepted,” and the word spouted has a negative connotation. (A connotation is a feeling associated with a word.) What sort of approach is favored instead of generalizations? A nuance is a “shade of meaning” or a “fine distinction.” Thus, Choice (B) works better than (E) because the subject is complex, not basic.

6. E. If technology is pervasive (all over the place), it’s bound to have an effect on just about everything, including society and culture. Choice (A) doesn’t work because innovative means “new,” and you don’t want to say that new technology is new. The other choices, redundant, (repetitive), lucrative (profitable), and versatile (useful in many ways) don’t fit the sentence because they don’t imply an essential study.

7. A. If your nose is always in a book, you have a fierce appetite for reading — in other words, a voracious appetite. (Good thing books aren’t fattening.) I don’t know of any reading competitions, so Choice (B) isn’t a good answer. The sentence doesn’t tell you anything about the subject’s approach to reading, so you have no way of knowing whether he was taught to enjoy reading or whether his habit was instinctive — Choice (C). Choices (D) and (E) — implausible (unbelievable) and sporadic (occurring from time to time) — just don’t fit the context of the sentence.

8. C. The but in this sentence tells you that you need opposites. At first glance, Choice (A) seems like a good candidate because education doesn’t happen suddenly. (Trust me. I’m a teacher and I know.) But the two words aren’t really opposites, so Choice (A) isn’t the best answer. Choice (C), on the other hand, has exactly what you’re looking for: Haphazardly is the term for things that are done without planning.

9. C. The author of this passage is shocked by the rapid mobilization of Belgian forces. One day they’re nowhere (at least in the author’s universe), and the next, they’re “passing the house all day” (Lines 7–8). Therefore, it’s reasonable to assume that the author didn’t see the army’s preparations for the march. Choice (A) doesn’t work because the author makes no comment on the quality of the troops in the passage. The passage flatly contradicts (B), as the author sees the troops on the road. You can dump Choice (D), too, because when you say as if by magic,you’re actually ruling out magic. Choice (E) is a close second to the correct answer, because as if by magic includes an element of surprise. However, (C) is better because it refers to the sudden appearance of the army, not the army’s general ability to mobilize.

10. E. Agog (Line 11) is a word that describes the mouth-open, I-can’t-believe-what-is-happening state of mind. The community may be agog for many reasons, including nondeadly ones, so you know Choice (A) is wrong. Choices (B), (C), and (D) are observations of relatively innocent activities, so you can drop them from consideration, too. Choice (E), on the other hand, hits the “deadly” button right on the mark because the line preceding deadly earnestness says “how one gives for one’s country” (Line 46). What do women give? According to the passage, their sons, who may die in defense of Belgium.

11. A. Just past the phrase “positively charged” (Lines 10–11) is a reference to the community as “agog” (Line 11), which means “filled with excitement.” Hence, positively charged is a metaphor for that human emotion. Choices (B), (C), and (D) are too negative. Choice (E) may have tempted you because of the word positively; however, optimistic doesn’t convey the feeling of anticipation so intense that it resembles an electric current. No doubt remains: Choice (A) is your answer.

12. D. The soldiers in the third paragraph (Lines 27–38) aren’t serious figures in a fight to the death with the enemy. In this paragraph, they’re “boys” (Line 27) who have just awakened and are hungry, so Choice (D) is the answer you seek. Although “Monsieur X” (Line 28) helps out, he’s not presented as a model to others, so (A) is wrong. The passage doesn’t criticize him and the Government when the soldiers overrun his ability to provide food, so you can also eliminate (B) and (E). True, the cook’s patience does give out, but the author writes that “even Dutch patience was at last exhausted” (Lines 35–36), implying that most people would have balked sooner than the cook. Hence, (C) doesn’t fit either.

13. D. The selected lines explain that the Government has taken what it needs for the war, including livestock and personal possessions. Yet the writer doesn’t hint that these seizures are in any way unjustified. On the contrary, the writer lists them as examples of “how one gives for one’s country” (Line 46). Thus, you can drop (A) from your list of possible answers. Because the writer says that “men [give] their goods; the women [give] their sons” (Lines 46–47), you may have considered Choice (B) or (C). However, goods and sons aren’t equal, and, by giving their sons to the war effort, the women place patriotism above family. The declaration that the “spirit of the people is magnificent” (Lines 47–48) seals the deal, because all the sacrifices listed in the paragraph are, according to the writer, done in the right spirit — in other words,willingly, making (D) the answer you seek. You can reject (E) because these lines don’t express fear at all.

14. A. Passage I describes events in Belgium following Germany’s declaration of war on Russia. The “supply of things” (Line 56) and the fact that troops have already eaten some of the family’s food supply (Lines 37–38) suggest that strolling to the local supermarket to restock might not be possible. From this statement you can infer that the author of Passage I would endorse Choice (A). The only other answer that comes close is (E) because the family is preparing for “necessity” (Line 56). Nevertheless, the author doesn’t protest the fact that the “Government . . . is commandeering” (Lines 42–43) various items. Therefore, no family is independent but rather potentially part of the war effort.

15. C. Though the author mentions some deadly realities of war (the sacrifice of sons to the war effort), the overall tone is that of an excited observer, relating what occurred after war was declared. Her comment “what excitement all about” (Line 10) points you to Choice (C). Although (D) is a close second because the author seems a little dazzled by what she sees, the word amazed requires more of an I-can’t-believe-what-happened attitude than you see in the passage.

16. E. Here’s a straight factual question, checking to see whether you were paying attention at the beginning of Passage II. Lines 64–66 specifically state that “Europeans being comparatively close to their homes, were not in straits as severe as the Americans.” Bingo! Choice (E) rules.

17. A. This paragraph refers to “American refugees” who were traveling to London in “floating hells” (Lines 92–94). Anything that resembles hell may be described as dire, which means “in serious or desperate circumstances.” Londoners, on the other hand, were “excited over the war and holiday spirit” (Lines 94–95). Hence, Choice (A) is the best answer.

18. B. As always with vocabulary-in-context questions, turn to the sentence and plug in a word that makes sense to you. You already know that Americans were “pleading” for transportation home (Lines 95–98) and that they formed a “preliminary organization to afford relief” (Lines 106–107). What can “pinch” (Line 108) and require “relief” (Line 107)? Choices (B) and (C) are good candidates, but pinch already expresses discomfort, so (B) is the best answer.

19. A. Every paragraph of Passage II talks about Americans in Europe at the outbreak of World War I, so Choice (A) works perfectly here. True, money is mentioned frequently in Passage II and the Americans certainly weren’t having a good vacation, but Choices (B) and (C) are too general, as is (D). Choice (E) is too narrow; the formation of a self-help society is mentioned only in passing (Line 106).

20. C. Passage I is an account of an eyewitness, a Belgian, who describes the immediate neighborhood in the wake of Germany’s declaration of war. Passage II steps back a little, recounting the plight of Americans stranded in Europe during the same time period and providing an overview of their plight. Choice (C) is clearly your answer because eyewitness accounts are always personal.

21. D. Lines 3–12 state that “the problem” with water “usually becomes an individual one” and that the “country dweller knows less about his source” than a city dweller who “chooses to investigate.” The implication is that the country dweller faces a water problem alone, in a practical way, as illustrated in the last two questions in the passage (Lines 12–15). Thus, Choice (D) is the answer you seek.

22. A. Just about every line deals with water, and the passage begins with “The water question” — a sure sign that the writer is going to answer that question. Hence, Choice (A) makes the most sense.

23. D. You know something mysterious showed up because “what we had beheld” (Line 6) filled the observers with “mystery dread.” However, the narrator cites the “extraordinary atmospheric attributes” (Lines 7–8) as a probable cause of the mystery, not as the mystery itself. So you’re left with a vocabulary-in-context question. In this case, Choices (B) and (C) are probably too narrow, and (A) isn’t a quality of the atmosphere. Hence, Choice (D), the weather, is the answer you want.

24. C. This short passage hints that something (think a Halloween-scary sort of something) showed up one night, but the next day the narrator proved “almost” (Line 9) that whatever they “had beheld” (Line 6) was a trick of the “extraordinary atmospheric attributes of these highlands” (Lines 7–8). In other words, the weather in the highlands scared the pants off the narrator and Drake. Because Drake “was not convinced” (Line 10), you have to look for an opposing view, which is expressed only by Choice (C).

Section 3: Mathematics

1. C. Average speed equals total distance divided by total time, not just the average of the two speeds. The student traveled 20 feet over the first 2 seconds and 45 feet over the next 3, which makes 65 feet ÷ 5 seconds, or 13 feet per second.

2. E. Probably the easiest way to do this problem is to change the numbers to decimals: a = 1⁄2 = 0.5, b = 2⁄3 = 0.666. . . , and c = 5⁄8 = 0.625. Now that you have decimals, you can see that a < c < b.

3. A. The best way to solve this problem is to substitute each answer choice into the given equation. Lucky for you, (–2)3 = –8, which is less than –2, so you can stop checking the possibilities right there.

4. D. To get from point S to point P, you have to move n spaces to the left, so the same must be true to get from R to Q. That fact tells you that the x-coordinate of Q must be c – n.

5. B. Don’t fall into the old “odd-integers trap!” Even though the numbers are odd, they still must differ by 2. (If you don’t believe me, think of 3, 5, 7 . . . .) Because the question tells you that the second number is x, the first one must be 2 less than x, or x – 2.

6. D. The easiest approach to this question is to pick numbers. Remember: When you take this approach, don’t pick numbers that are too simple. Here, for example, you shouldn’t pick 12 and 20 themselves, nor should you just multiply each one by the same number. Instead, try doubling 12 to get 24 and tripling 20 to get 60. If you add them together, you get 84, which is divisible by 2 and 4, but not 32. This result makes sense because both 12 and 20 are divisible by 4. Therefore, you can expect your answer to be divisible by 4, too (and, thus, also by 2).

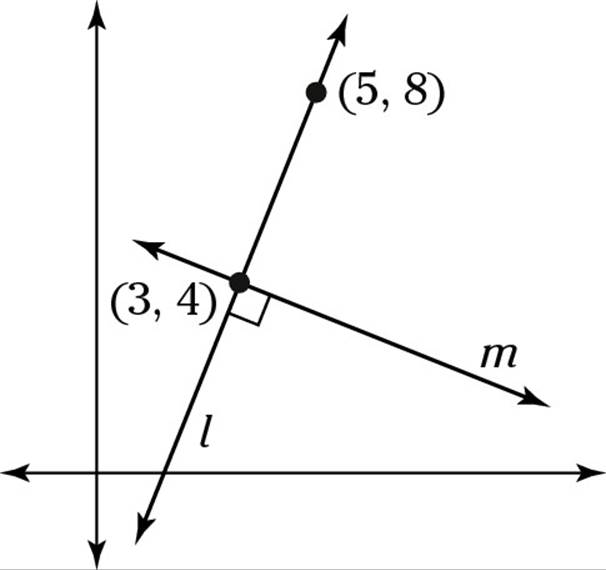

7. B. I’d start by making a quick sketch:

Perpendicular lines have slopes that are negative reciprocals, so first find the slope of l:

![]() . That means line m has a slope of –1⁄2. Now you can just put some of the given

. That means line m has a slope of –1⁄2. Now you can just put some of the given

points on the line by counting spaces on improvised graph paper (draw your own lines), or you can try plugging the answer choices into the slope formula, in which case plugging

in Choice (B) gives you ![]() .

.

8. B. This trapezoid has a rectangle in the middle, a 45-45-90 triangle on the left, and a 30-60-90 triangle on the right, so I suggest dividing it up into its three pieces. The rectangle’s area is just 4 × 10 = 40. The left triangle is isosceles, so its base and height are both 4, and its area is (4× 4) ÷ 2 = 8. In the triangle on the right, 4 is the shortest side, which makes the hypotenuse 8 and the base ![]() . Thus, its area is (4 ×

. Thus, its area is (4 × ![]() ) ÷ 2 =

) ÷ 2 = ![]() . Putting them all together gives you Choice (B).

. Putting them all together gives you Choice (B).

9. 100. Just subtracting x from each side gives you the answer here.

10. 4. You can solve this problem by using trial and error or by letting l = 2w, writing (2w)(w) = 32, and then solving for w.

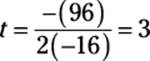

11. 144. When I took the SAT, graphing calculators weren’t in existence, so I had to work this one out by hand. Luckily, times have changed, and you can just plug the numbers into your calculator to find the answer. If you don’t have such a magical device, rely on the

formula that says the vertex of a parabola occurs at ![]() , where b is the x-coefficient and

, where b is the x-coefficient and

a is the x2-coefficient (although here you’re using t, not x). Plugging in here tells you that

the vertex occurs when  , and plugging this result into the original equation gives you h = 144.

, and plugging this result into the original equation gives you h = 144.

12. 170. 20 percent is one-fifth, and one-fifth of one-half is one-tenth, so the original number was 10 × 17 = 170.

13. 400. The graph tells you that 65% of the students take either French or Spanish, so you can

use the old is-of formula: ![]() . Here, the number you know, 260, is 65% of the number

. Here, the number you know, 260, is 65% of the number

you’re looking for, so you can write ![]() . Cross-multiplying gives you 65x = 26,000,

. Cross-multiplying gives you 65x = 26,000,

and, thankfully, 65 goes into 26,000 a nice, even 400 times.

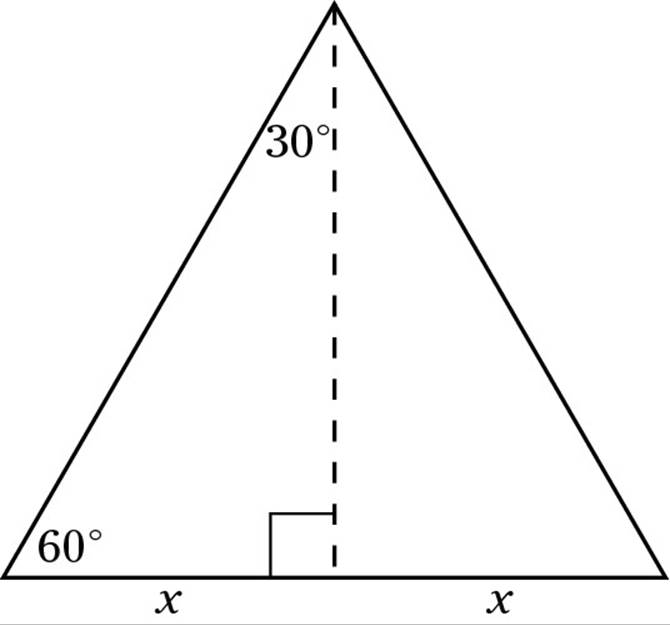

14. 16. To solve this problem, I recommend creating a simple sketch:

An equilateral triangle can be divided into two 30-60-90 triangles, as you can see in my sketch. If you let each side of the base equal x, then the height equals ![]() . Because the area is half the base times the height, the area is

. Because the area is half the base times the height, the area is ![]() , which means that x2 = 64, and x = 8. But wait! xwas half the base, not the whole base, so your answer is 16.

, which means that x2 = 64, and x = 8. But wait! xwas half the base, not the whole base, so your answer is 16.

15. 12. The expression w2 – v2 is a difference of two squares, which factors into (w – v)(w + v) = 54. Because you know that w – v = 9 and that the whole thing equals 54, you can say that w + v = 6, so 2w + 2v = 12. Notice that you don’t know what w and v are individually but that you don’t really care, either. This reminds me of a story about a student who was both ignorant and apathetic . . . oh, never mind. (For more information on finding the difference of two squares, turn to Chapter 14.)

16. 60. You can actually ignore the 2 and 3 here because every number that’s divisible by both of them is also divisible by 6. Now, because the number is divisible by 4 and 5, it must also be divisible by 20 (because 4 and 5 have no common factors). If you try out multiples of 20, you see that 20 and 40 aren’t divisible by 6, but that 60 is divisible by 6, so 60 is your answer.

17. 27. Imagine that you have only the 9 vertices, and none of them are connected yet. Pick a vertex and connect it to each of the others, drawing 8 lines. Now pick another vertex and connect it to all the vertices. It was already connected to the first vertex, so you draw 7 new lines. The third vertex will already be connected to the first and third, so it needs only 6 new lines. After all the vertices are completely connected, you will have 8 + 7 + 6 + 5 + 4 + 3 + 2 + 1 = 36 lines. The original drawing already has 9 of those lines drawn in, so you need 36 – 9 = 27 more lines.

18. 400. Car A costs 80d + 0.25m, where d is days and m is miles. Car B costs 100d + 0.10m. If you plug in 3 for d and make the equations equal, you get 240 + 0.25m = 300 + 0.10m. Combining like terms gives you 0.15m = 60, and dividing gives you m = 400.

Section 4: Critical Reading

1. D. If people are debating, they don’t agree. So what hasn’t emerged? An agreement, otherwise known as a consensus. Therefore, Choices (A), (B), and (C) are out because they imply disagreement — the reverse of what you need in this sentence. Choice (E) seems possible at first, but plan implies action, and nothing in the sentence refers to action. In fact, a constitution is more of a theoretical structure by which actions are measured. Thus, (D) is the answer you’re looking for.

2. B. To “trust and depend upon each other” is another way of saying that the group will stick together and work as a team, a quality best expressed by Choice (B) — cohesive. Choice (C) may have fooled you, but an adhesive is the glue or substance that sticks one thing to another, a meaning that doesn’t fit with depend upon each other. Choice (D) is tempting, too, because groups should communicate. However, communication isn’t enough to justify trust and depend, especially when the communication runs along the lines of “You’re fired!” or “Don’t look for a raise during this century.”

3. E. If your boss wants to know what you think, he’s inclusive. In other words, he pulls everyone into the inner circle. A close second, but not the correct answer, is (B), because the “let’s all sit and talk as equals” sort of boss is probably idealistic. However, the sentence specifically mentions that subordinates are supposed to share their thoughts with the boss, a statement that tips the scale toward inclusive. Hierarchical, by the way, is a system characterized by levels of power — the type of system in which subordinates’ ideas are generally not welcome.

4. C. The very first word of the sentence sets up a comparison between negotiations resembling war (lawsuits and ill will) and something else. So you’re looking for a contrast, and Choice (C) fills the bill. The only other possibility is (B) because law suits take forever, and swiftexpresses the opposite. However, harmonious works as a contrast to both lawsuits and ill will, making (C) the best answer.

5. A. This one is pure vocabulary. If you know the answer choices, you’re in. If they puzzle you, you’re better off skipping this question. Quotidian means “everyday” and refers to the day-to-day activities that fill your time. The question mentions daily strolls, so this answer fits perfectly. The other choices simply don’t work; exemplary is “ideal; the standard model,” inexplicable is “unexplainable,” as in all those strangely plotted TV shows involving flying islands and time travel, tenacious is a fancy way of saying “stubborn,” and estranged is “separated; not speaking,” as in an estranged spouse who is headed for divorce court.

6. C. When an author says that “the radicals would have us believe,” you know that the author doesn’t believe whatever comes next in the sentence or paragraph. The rest of the excerpt is devoted to explaining the position of “the radicals” (Line 1), which is that the “man’s world” (Line 4) should become “a human world” (Line 5) and, “with the single exception of childbearing” (Line 9), all work should be open to the “[human] race” (Line 11), instead of to only one gender. After you decode the paragraph, all you need to do is find a statement that contradicts the radicals’ position, which is (C).

7. A. The introduction to these passages (the text in italics that appears before the passages) helps you out with this question. The bank makes loans to poor women, not to poor people. Clearly, this bank supports female financial independence. Even if you skipped the introduction — something you should never do — you still see evidence in the passage that supports Choice (A). The bank wants to know whether a woman can stand up for herself and not “turn over money” (Line 18) “to her husband” (Line 19) as a “lifetime of oppression” (Lines 15–16) may have taught her to do.

8. D. Though several answers here are synonyms for race, only Choice (D) fits the sentence, which emphasizes neither man’s work nor woman’s work (Line 10) but the work of the human race.

9. B. Lines 21–23 state that the screening process checks whether a woman, faced with a demand from her husband for money, would “alert her group members and center chief and ask them to intervene.” Thus, Choice (B) is the answer you’re looking for.

10. D. This passage, an excerpt from David Copperfield by Charles Dickens, displays Dickens’s famous ability to create a character with just a few words. Miss Murdstone’s “very heavy eyebrows” (Line 4) are described as the whiskers (facial hair) she would have on her chin and cheeks if she were a man. The wording is a little confusing, so this question is really testing whether or not you can decode old-fashioned and complicated expressions. Here’s the translation: Miss Murdstone is “disabled by the wrongs of her sex” (Lines 5–6) (women don’t, in general, have whiskers!), and she “carried” (Line 7), or wore, the eyebrows “to that account,” which in modern terms would be on account of that fact or because of that fact.

11. A. Miss Murdstone is literally covered with metal. Choice (B) is wrong because her “hard black boxes” (Lines 8–9) have “her initials on the lids in hard brass nails” (Lines 9–10). Choice (C) is out because her purse is made of “hard steel” (Line 11). You can eliminate (D) and (E) because the purse is kept in a “jail of a bag” (Line 12) and suspended by a “chain” (Line 13). Jails are characterized by metal bars, and chains are usually made of metal. All that’s left is her disposition, or tendency, which is certainly nasty but not made of metal.

12. B. The narrator has just heard Miss Murdstone say, “Generally speaking . . . I don’t like boys” (Lines 20–21), followed by the social formula, “How d’ye do” (Line 22), which is “How do you do?” in modern terms. It’s not surprising that the narrator’s response, hoping that Miss Murdstone is well, doesn’t have a lot of sincerity in it. She starts the social formality of asking how you’re doing, and he finishes it in a mediocre (so-so or unexceptional) way.

13. D. According to the narrator, Miss Murdstone’s room is “from that time forth a place of awe and dread” (Lines 29–30). Dread is another word for extreme fear, so (D) wins the gold medal for this question. Did (E) catch your eye? The SAT-makers like to throw in an answer that appears in the passage but doesn’t answer the question they’re asking. Miss Murdstone is supposed to “help” (Line 40) the narrator’s mother, but the narrator’s relationship with Miss Murdstone isn’t included in that statement. Besides, as the next question points out, “help” isn’t exactly what Miss Murdstone supplies.

14. E. Most of the time, quotation marks signal that you’re reading the exact words of a character (or, in nonfiction, of a real person). However, quotation marks can also indicate a gap between intention and reality. Miss Murdstone is supposed to be helping, and she may even have used that word in describing her own actions. But later in the sentence, the narrator says that she made “havoc in the old arrangements” (Lines 42–43) by moving things around. Havoc means “chaos,” and creating chaos doesn’t help anyone. Thus, Choice (E) is the best answer.

15. A. When Peggotty says that Miss Murdstone “slept with one eye open” (Line 57), Peggotty is describing Murdstone’s vigilance, or watchfulness, in fanciful terms (with a figure of speech). The narrator says that he “tried it” (Line 58) and “found it couldn’t be done” (Line 60) because he accepted Peggotty’s words as the literal, or actual, truth. His confusion comes from his ignorance; he’s just too young to separate a figure of speech from reality. The only other possibility is Choice (E) because the narrator does experiment with his own sleep. However, (A) is better because the narrator isn’t questioning Peggotty’s comment (and inquisitive means “tending to ask questions”). Instead, he’s trying to duplicate what he believes is Miss Murdstone’s habit.

16. B. If you know that advent means “arrival or beginning” and inception means “a start or foundation,” you’re all set for this one. The passage states that “the advent of cultivated grains in human society is closely associated with the inception of the city and civilization” (Lines 6–8). The very next sentence tells you that “around 10,000 B.C. grain began to be cultivated” (Lines 8–9). Put those two thoughts together, and you see that Choice (B) is correct.

17. D. Lines 11–22 list the many places that rice grows, and a quick glance reveals that rice plants may be found along rivers (A), in the mountains (B), in the desert (C), and in the tropics (E). What’s left? A statement about rice and other grains, (D), which tells you nothing about theadaptability, or flexibility, of the plant.

18. E. The passage refers to the “durability in storage” (Lines 17–18) of rice. So if you dump a ton of rice into your kitchen closet, it’s not likely to spoil because of its hardiness (ability to endure and survive). The other choices, all synonyms of durability, are best used in other situations. If you’re purchasing a chair for your three-ton elephant to sit on, go for (A), (C), or (D). When you buy an engagement ring, you hope that the relationship has the sort of durability expressed by (B).

19. C. Even if the word stagnation is unfamiliar to you, you can still answer this question by putting on your detective hat and searching for clues. The last sentence of Paragraph 1 mentions “thousands of years of sameness and virtual stagnation” (Lines 24–25). Right away you know that Choice (E) is out because you’re looking for something related to sameness. What didn’t change? Check out the next paragraph, which begins by explaining that “agriculture” (Line 28) replaced “hunting and gathering” (Line 30) — hello, Choice (C)! Did Choice (D) trick you? Because stagnation came before the cultivation of other food sources, (D) is a no-go.

20. A. According to Paragraph 2, “the primary economic endeavor” (Line 31) is cultivation, which “prescribed a revolutionary new social order — the city” (Lines 31–33). When cultivation (another word for agriculture) was invented, cities arose. The other choices illustrate a favorite SAT torture — sorry, I mean trick. Everything listed in Choices (B) through (E) appears in Paragraph 2, but all those facts serve to explain the cause-and-effect statement given in Choice (A).

21. E. This passage talks about rice, and rice is food. (Yup. There’s some in my refrigerator right now.) Because Choice (E) asserts that getting and eating food is a big part of human endeavor, or effort, rice is important and, therefore, has a prominent (important) place in history. Choices (A), (B), and (C) all discuss the rise of agriculture, but they provide reasons or time spans and don’t deal with the significance of rice. Choice (D) is close, but not correct, because “differentiating one civilization from another” (Lines 55–56) is less directly related to the importance of rice than (E).

22. C. A paragraph’s title is an umbrella that covers all the ideas in the paragraph but nothing beyond the paragraph. Using that standard, Choices (A) and (B) are too wide, and (D) and (E) are too narrow. Choice (C) covers all the areas mentioned in the paragraph — from Asia to Africa to Europe — and all the time periods (2800 b.c., 1000 b.c., and right now, when Americans pelt newly married couples with the uncooked grain).

23. B. What do an infant and a man who has been married for only a few minutes have in common? Both are beginning a new life, as Choice (B) states.

24. D. According to Lines 83–85, the “written character for cooked rice is . . . also the word for food” — pretty good evidence that eating rice is as basic as, well, eating.

Section 5: Mathematics

1. A. This question relies on old-fashioned algebra: subtracting 6 from both sides gives you 4n = 28, and dividing both sides by 4 gives you n = 7.

2. E. The missing angle in the triangle must be 30°. And because a and this angle make a straight line (180°), a must be 150° (the difference of 180 – 30). In case you’re interested, the great world of geometry has also come up with a rule for this sort of problem: The exterior angle of a triangle is always equal to the sum of the two remote interior angles.

3. D. Four even numbers are possible (2, 4, 6, and 8), so his chance of choosing 8 is just 1⁄4.

4. B. The total number of pets is 5 × 0 + 8 × 1 + 4 × 2 + 2 × 3 + 1 × 4 = 26. The total number of students is 5 + 8 + 4 + 2 + 1 = 20. There you have it: 26 ÷ 20 = 1.3.

5. B. The key here is being able to tell your dollars from your sense (sorry, I mean cents). You want an expression in cents, and a dollar is 100 cents, so your answer is 100 – 5n.

6. B. In a ratio problem, the total number of things involved (in this case, people) must always be divisible by the sum of the ratios. Here, 4 + 5 = 9, and all the numbers except 400, are divisible by 9.

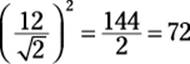

7. C. This question is a tricky case of the 45-45-90 triangle. The 12 on the triangle’s base is actually its hypotenuse, and the helpful formula list at the start of each math section tells you that the hypotenuse of this special type of triangle is ![]() , where x is the length of a

, where x is the length of a

leg. That means each leg must be ![]() , which is just an annoying number. But no fear! The

, which is just an annoying number. But no fear! The

leg of the triangle is also the side of the square, which means that the square’s area is

.

.

8. A. You can do this one by picking numbers, but you can also reason it out: If both numbers are odd, then xy is odd, but x + y is even, so (xy) – (x + y) is odd. But if one is even and one is odd, then the opposite happens, so the result is still odd. Only if both numbers are even will the result be even.

9. D. On a graph, f(x) just means the y-value for a given x. Looking at the graph, you can see that y = 2.5 when x = 1.

10. B. According to the Pythagorean Theorem, the hypotenuse equals ![]()

![]() . To find the perimeter, just add up the sides: 9 + 12 + 15 = 36. By the way, if you answered 54, you found the triangle’s area, not its perimeter.

. To find the perimeter, just add up the sides: 9 + 12 + 15 = 36. By the way, if you answered 54, you found the triangle’s area, not its perimeter.

11. C. Usually, factors come in pairs. For example, in the case of 10 you have 1 × 10 and 2 × 5. The only way to end up without a pair is if one of the factors involves the same number twice. You have the same number twice only if the number is a perfect square. Take 16, for example. You have 1 × 16, 2 × 8, and 4 × 4, which makes only 5 factors, an odd number. So how many positive perfect squares are less than 50? There are 7 such numbers: 49, 36, 25, 16, 9, 4, and 1.

12. A. The expression ![]() means “the distance between x and a.” In this case, you must be no more than 10 inches from a height of 60 inches. Another way to see that this is the right answer is to plug in 70 and 50 for h. Doing so eliminates all choices except for (A) and (E). Choice (E), however, gives you numbers on the “outside” of 50 and 70, but (A) gives you numbers on the “inside,” so (A) is right.

means “the distance between x and a.” In this case, you must be no more than 10 inches from a height of 60 inches. Another way to see that this is the right answer is to plug in 70 and 50 for h. Doing so eliminates all choices except for (A) and (E). Choice (E), however, gives you numbers on the “outside” of 50 and 70, but (A) gives you numbers on the “inside,” so (A) is right.

13. C. The hamster seems to grow between 4 and 8 grams per day, which means that 6 is a reasonable slope for the function. Because it weighed 15 grams after 1 day, it’s also reasonable for it to have weighed 10 grams or so at 0 days (although I have to admit that’s a pretty big hamster).

14. D. Here’s the deal: ![]() and

and ![]() , so

, so ![]() . Taking the cube root of both sides gives you

. Taking the cube root of both sides gives you ![]() , and taking both sides to the fourth power gives you x = 24 = 16.

, and taking both sides to the fourth power gives you x = 24 = 16.

15. B. The first equation factors to x(x – 9) = 0, the second to (x + 4)(x – 3) = 0, and the third to (x + 3)(x + 3) = 0. Therefore, the first has solutions of 0 and 9, the second of –4 and 3, and the third of –3 and –3. Two traps await you here. First, lots of people accidentally factor the first equation into (x + 3)(x – 3), but that’s x2 – 9, not x2 – 9x. The second trap is forgetting that the roots are the opposite of the factors, so 3 isn’t a solution to the third equation.

16. B. By the time you get to the 20th number, you’ve added three 19 times (not 20). Thus, you’ve added 19 × 3 = 57. Because you’re now at 55, you must have started at 55 – 57 = –2.

17. A. Because the circle’s diameter is 10, its radius is 5, and its area is πr2 = 25π. The square’s diagonal cuts it into two 45-45-90 triangles, so just like in Question 7, one side of the square

must measure ![]() , and its area must be

, and its area must be  . The shaded area just equals the

. The shaded area just equals the

circle’s area minus the square’s.

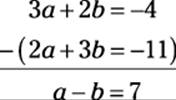

18. E. You can choose from a bunch of ways to do this problem, but the best is to notice that you can subtract the two given equations like so:

So 5a – 5b = 35.

19. A. The rule in this case says that if two figures are similar, the ratio of their areas is the square of the ratios of their sides. This rule holds true for any two-dimensional figure, whether it’s a triangle, a circle, or whatever. Because the ratio of the sides is 6:10, the ratio of the areas must be 36:100, and 36⁄100 × 50 = 18.

20. B. Let the wind’s speed equal x. Because the cyclist bikes 30 miles per hour without any wind, his speed was 30 + x with the wind, and 30 – x against the wind. With the wind, the trip took 40 minutes, but you have to convert this to 2⁄3 of an hour because you’re measuring speed in miles per hour. Similarly, against the wind, the trip took one hour exactly. The distance was the same both times, and distance equals speed times time. Bingo: 2⁄3(30 + x) = 1(30 – x). Distributing gives you 20 + (2⁄3)x = 30 – x, and regrouping gives you (5⁄3)x = 10. Finally, you can multiply both sides by 3⁄5, and x = 6. As befits the last problem in the section, this one is pretty hard!

Section 6: Multiple-Choice Writing

1. C. In grammar world, using the phrase equally as equals a felony. Justin’s coat may be equally ripped, but it can’t be equally as ripped. Therefore, Choice (A) is wrong. The second issue in this sentence is what you’re comparing. Choices (B), (D), and (E) compare Justin’s coat — an item of clothing — to Anthony, a person. You know that’s not the intended meaning. You can rip a coat but not a person. You’re left with Choice (C), the right answer.

2. E. The original, as well as Choice (C), joins two complete sentences with a comma. Uh oh — no can do! Commas are very useful punctuation marks, but they’re not strong enough to link sentences. Choice (B) avoids the comma problem by throwing in a pronoun (which). However, the combination of the two pronouns together (which it) isn’t Standard English. Choice (D) isn’t wrong grammatically, but it’s wordy and thus not as good as (E).

3. D. By definition, a grandfather is a relative. All the answer choices, except for (D), exclude Libby’s grandfather from the category of relative. The crucial word other keeps Grandpa in the family, though it doesn’t help him with the metal detector.

4. D. You don’t need had unless you’re placing one event before another in the past. In this question, the wobbling and the destroying are simultaneous, so (A) is wrong. Choice (B) solves the tense problem but creates a pronoun error. Which may not refer to a subject/verb combo. In Choice (B), which refers to “the spotlights wobbled a little.” Penalty box! Choice (C) adds an unnecessary it, and (E) distorts the meaning with because. Choice (D) correctly pairs the subject spotlight with two verbs, wobbled and destroyed.

5. B. When a sentence begins with a descriptive verb form, the verb form has to describe the subject of the sentence. In the original sentence, “selecting a new chief executive” describes problems. But the problems aren’t selecting anything; the trustees are the ones selecting. Now that you’ve dumped (A) and (C), go for the shortest and most fluid expression, which is (B).

6. A. The verb is functions as an equal sign in this sentence, so whatever is in front of the equal sign must have more or less the same grammatical identity as what follows it. Reason is a noun, and “that the operating system code contains an error” is a noun clause. Don’t worry about the English-teacher lingo. Just flip the sentence to see if it still makes sense. If it does, chances are it’s correct.

The reason is because or the problem is because or just about any noun followed by is because is all wrong, all the time.

The reason is because or the problem is because or just about any noun followed by is because is all wrong, all the time.

7. D. SAT questions are created by teachers, and teachers don’t enjoy marking papers. The faster we finish, the happier we are. If you plop unnecessary words into your sentences, we mark them out with a red pencil. Choice (D) does the same basic job as (A), but (D) is shorter; therefore, it’s the answer the SAT writers want.

8. C. This sentence begins with a descriptive verb form (rushing), which must describe the subject of the sentence. The seat can’t be rushing, so Choices (A) and (B) are nonstarters. Of the other three choices, only (C) and (D) make a complete sentence. Because (C) is more concise, it edges out (D).

9. D. Parallel lines look the same, and so should elements of the sentence that do the same job. This principle of grammar is called parallelism, which is often a hot topic on the SAT. Choice (A) isn’t correct because to ski doesn’t match knowing karate. (You absolutely have to know the grammar terms? Fine: To ski is an infinitive and knowing karate is a gerund. Happy now?) Choice (B) looks okay at first because the to may be understood. However, you can’t say to karate. Thus, (D) is the only answer with three matching items.

10. B. Why repeat lived and living? Go for Choice (B), which expresses everything you need to know without adding any extra words.

11. A. This sentence — along with, come to think of it, all English sentences — requires agreement. Singular subjects have to pair with singular verbs, and plural subjects with plural verbs. The subject of the sentence is reporter, which is a singular word, so the singular verb has is correct. The long interrupter (“as well as many other representatives of the media”) appears to add people and, therefore, to create a plural subject. But appearances, as Internet daters know, may be deceiving. Grammatically, as well as doesn’t have anything to do with reporter. Thus, Choice (B), the plural verb have, is a trap the SAT makers set up to make sure you’re paying attention.

12. D. Tense is the quality of the verb that expresses time. You can’t switch tenses without a reason, just as you can’t set your teacher’s clock two hours ahead in order to get out of school early. The sentence begins in past tense (with began and entered) and then switches to present tense (with repeats). Penalty box!

13. E. Yup. This one has no error. Did (B) or (D) trick you? The commas are correct because they set off the false statements from the true ones.

14. B. Neither pairs with nor and either with or. Don’t mix and match!

15. D. Which object has a roomy interior — the box or the chest? The pronoun its doesn’t tell you, and the first goal of writing is communication. Change the pronoun to a noun (either the box’s or the chest’s) and the meaning is unmistakable.

16. B. Milo isn’t attempting two separate actions: trying and arriving. Instead, he’s going to try to arrive — one action.

17. A. The contraction who’s means who is. The word needed in this sentence is the possessive whose.

18. A. The first verb in the sentence (is) is in present tense, but the rest of the sentence employs past-tense verbs (was committed, convinced, and was). Grammar rules prohibit littering, talking in class . . . sorry, wrong list. Grammar rules prohibit unnecessary shifts in tense, so Choice (A) contains the error.

19. B. The SAT sometimes checks basic knowledge — whether you know some common expressions that are correct simply because they’re the way people speak and write. Question 19 falls into this category. Standard English calls for accidents in which, not accidents to which.

20. B. Either and or are a pair. Whatever elements of the sentence they join must have the same grammatical identity. In the original sentence, a complete sentence (“the sewing machine is defective”) comes after the either, but only a partial sentence (“cleaned . . . water”) follows theor. The correct version, by the way, is “Either the sewing machine is defective or it was cleaned improperly with an oil-based solution instead of soap and water.”

21. B. The pronoun I works for subjects, not objects. In this sentence, you need an object because you have a preposition, to, and all prepositions require objects.

When you have a combination of a noun and a pronoun, take your finger and cover the noun. Read the sentence again. Often the right answer becomes obvious. For example, in Question 21, you’d hear “given to I.” It sounds wrong, doesn’t it? That’s because it iswrong.

When you have a combination of a noun and a pronoun, take your finger and cover the noun. Read the sentence again. Often the right answer becomes obvious. For example, in Question 21, you’d hear “given to I.” It sounds wrong, doesn’t it? That’s because it iswrong.

22. D. Who hadn’t yet recovered from a cold? George or Chester? It might be George because George had laryngitis and, therefore, sounded odd. Or it might be Chester, whose ears were stuffed. The pronoun he is the issue here. Insert a name, and you know what’s going on. Without a name, you’re lost.

23. E. Ignore the interruption between the commas, and you see that the singular verb has been matches the singular subject editor.

24. C. Some descriptions — those that aren’t essential to the meaning of the sentence — are set off by commas. To set off a description that lies in the middle of the sentence, you need two commas, and in Question 24, one comma is missing. You need to insert a second comma aftergreenhouse.

25. D. This sentence presents a comparison problem. Hardest compared to what? Hardest of all the designers? Hardest in the company? The sentence doesn’t say, so the comparison is incomplete. You may be wondering about the hyphen in Choice (B). When two words combine to form one description, they’re joined by a hyphen.

26. D. I have no idea why between you and I is such a popular (but incorrect) expression. The preposition between calls for an object, and I can serve as a subject, not an object.

27. C. The subject of the sentence is bandage, a singular noun, so you have to pair it with the singular verb was. In case you’re wondering, further means “more intense or additionally.” Farther refers to distance.

28. B. In 99 percent of all English sentences, the subject comes before the verb. (Okay, I made the number up. I have no idea what the percentage is; I just know that most of the time, you see the subject and the verb in that order.) In Question 28, the usual pattern is reversed, and the subject of the sentence follows the verb. The compound subject (“the eyewitness testimony and the fingerprints”) is plural, so you need the plural verb were, not the singular was.

29. B. The expression real important is fine for conversation, but in Standard English, you need really important. Why? Because real is an adjective and may describe a noun, as it does in phrases like the real reason or a real test. Really, on the other hand, is an adverb, and its job is to describe a verb or a descriptive word, such as important.

30. C. All three sentences in Paragraph 1 deal with the type of food served in school cafeterias and the way in which teenagers relate to that food (although if this were a realistic essay, food fights would be in there somewhere). The first sentence of that paragraph needs to establish the author’s point of view. Of the five given answers, Choice (C) best expresses that point of view: Give teens more appropriate choices, and they’ll eat in a healthier way.

31. A. In Paragraph 2, the author explains how both economics and taste matter when cafeteria menus are created. Paragraph 1 asserts that school lunches aren’t always healthful. The goal of Question 31 is to join these two ideas with a transition. Choice (A) refers to the ideas in Paragraph 1 and the ideas in Paragraph 2, making it a fine transitional sentence. Although Choice (B) is attractive at first glance, it’s too general to be an effective transition. Economics and taste where? In what context? Choice (B) doesn’t say. Choices (C) and (D) are just plain wrong, and (E), although true, isn’t the topic of this essay.

32. E. When you combine sentences, your goal is a smooth, concise result. Of course, you also need to include all the relevant ideas. The two best candidates here are (A) and (E). Choice (A) loses out to (E) because (A) uses passive voice — is bought, grown by. Choice (E), which employs active verbs — comes, buys, distributes — is your winner.

33. B. The original version of Sentence 8 matches the noun student (which is singular) with the plural pronouns their and they. Penalty box. In the world of grammar, you must pair singular with singular and plural with plural. Also illegal is a shift in person. Choice (A) starts out in third person, talking about the student, and then shifts to second person (you). Choice (B) is consistent: the third-person plural students matches third-person plural pronouns.

34. C. Subjunctive voice, a grammar term you don’t have to know, is what they’re testing in this question. I won’t go into technical detail; all you have to know is that when you have an if sentence that expresses something untrue, you don’t want to insert a would into the if portion of the sentence. Instead, go for were, as in “if I were the Queen of Grammar.” Choice (C) acknowledges that junk food is offered, so subjunctive is appropriate.

35. D. The last paragraph is the author’s recommendation for change. Sentences 12 and 13 talk about crops and taste — topics covered in Paragraph 2. Repeating them in the third paragraph serves no purpose.

Section 7: Critical Reading

1. A. The sentence hinges on the word but, which signals a change in direction. The verb pretends is another clue; George creates an appearance, but the reality doesn’t match it. Okay, what’s the reality? He practices many hours each day. The appearance must be different from this reality, so you’re looking for a talent that just shows up and doesn’t have to be learned (in other words, an innate talent). Choices (B) and (E) also refer to qualities that are hardwired, not taught. However, instinctive usually refers to actions that have to do with survival (eating, running from danger, and the like), and intuitive describes information, not talent.

2. C. When you read the sentence, did a little picture pop up in your mind? Probably, which is why vivid, a word meaning “producing strong or clear mental images,” is right on target.

3. B. The key to this sentence lies at the end — the possessive phrase his opponent’s punches. The boxer’s hopping isn’t aimed at the opponent; it’s aimed at the punches. You can’t confound, or confuse, a punch. Nor can you distract one. Therefore, cross out Choices (A) and (E). The hopping doesn’t counter (oppose) or resist the punches either, so (C) and (D) are also out. The act of hopping simply moves the boxer around so he can evade, or avoid, getting a broken nose from the opponent’s punches.

4. E. The word quaint refers to something charming and a little out-of-date, as in the sentence I hear all the time: “You don’t have a cellphone? How quaint!” The cottage falls into that category easily. Did Choice (C) fool you? Simplistic doesn’t mean “simple.” It means something that’s overly simplified — a quick and easy route that can’t substitute for something more complex.

5. B. Because of the pairing of the words not just and but, the sentence implies a progression or an intensification. The only answer that falls into this category is (B). If you’re assertive, you don’t hesitate to put yourself forward, as in “You should listen to what I have to say.” If you’reaggressive, you approach violence, as in “Listen to what I have to say or you’ll regret it!”

6. B. When the temperature drops, ice generally forms or, if it’s already there, continues to exist. The word despite in the sentence alerts you to the need for an unusual occurrence — a break in the pattern. Choice (B) is the only answer that moves away from existence toward nonexistence.

7. A. The narrator says that she’s “not there” (Line 11) and that she pays little “attention” (Lines 18–19) to family members as they walk in and out of the room. Choice (A) expresses the sense of solitude that the narrator implies when she says she sits “on the floor in the middle of the living room” (Line 3), almost like an island. True, Choice (B) expresses the events that are on the television screen — “demonstrators and police” (Lines 8–9) — but those events don’t capture the narrator’s attention; she’s disconnected. Hence, Choice (A) works better. Choice (C) fails because the narrator seems in control at this point. The decision to leave has been made, and any alterations are up to her, as confirmed in the father’s statement, “You don’t have to go” (Lines 87–88). Choices (D) and (E) aren’t even in the running.

8. D. Choice (D) is a statement of fact, an observation. The other choices all revolve around the narrator’s feelings of detachment or alienation from the family. Choice (E) is a runner-up because the narrator comments on her family (“I want them to go away”), but (D) is more impersonal and, therefore, the better choice.

9. E. You can use the process of elimination to find this answer. Choice (A) can’t be correct because the father’s statement in Lines 87–88 (“You don’t have to go”) shows that at least one other family member doesn’t want the narrator to leave. However, you don’t know anything about Bobby’s opinion, so you can’t select (B) either. Choice (D) doesn’t work because, although the mother is worried about toothpaste and shampoo (Lines 28–30), a lack of toiletries hardly qualifies as danger. Choices (C) and (E) are opposites. The mother’s preparations and her statement that “these things are from home” (Lines 32–33) show that the narrator’s interpretation is correct, making (E) the right answer.

10. C. The full statement from the mother concludes with “these things are from home” (Lines 32–33). Taken together, you have a comment on the unknown (“you don’t know what you can buy there” — Lines 30–31) and a tie to familiar places (home). So Choice (C) makes a lot of sense. Any of the other responses might be true, but the passage gives you no evidence to support them. The passage doesn’t mention either money or the quality of European shampoo and toothpaste. Because the reader has no way to figure out how much the mother has traveled, (D) isn’t correct.

11. B. The information about the trunk’s drawings is the key here. They appear “cartoonish” (Line 34), similar to a child’s drawings. The trunk description is tucked into a paragraph listing what the narrator hasn’t done – flown on a plane, eaten alone in a restaurant, and so forth. Lack of experience is associated with youth (yes, I know, sometimes this association is unfair or just plain wrong), so Choice (B) is bubble-worthy.

12. C. Throughout the passage, the narrator scatters some clues about her alienation from her family, and this phrase — as well as the paragraph it appears in — is a big one. The narrator wants to be in a land where she isn’t “the youngest, weakest link” (Lines 56–57). In the real world, therefore, she is the youngest and weakest. The language no one else understands is a way to be different, to have her own place separate from her family, an idea expressed in Choice (C).

13. A. This one is easy. Some of the answers are just plain wrong because information in the passage clearly contradicts them. You can drop (C) because French, not Spanish, is cited by the narrator’s mother as being “cultured” (Lines 58–59). Lines 48–49 tell you that the summer course was not remedial; thus, (D) is also incorrect. The narrator didn’t make it to South America because “Mom said no” (Line 68), so (E) is wrong, too. The only choices left are (A) and (B). Because this is the narrator’s first trip to Spain and she says nothing about the country itself, (B) isn’t a good option. Bingo: One order of teen rebellion coming right up.

14. C. “Then” (Line 84) is the key to this question. First, the narrator tells you what she thought at the time: “He hardly ever asked me for anything” (Lines 83–84). Next, the narrator qualifies this statement with a time clue, “I thought then” (Line 84). Clearly, the narrator’s idea of her father changed, which leads you to Choice (C). Choice (A) is too general; the whole passage explains how the narrator thinks. Choice (B) is tricky: Yes, the narrator implies that she feels obligated, but the words implying this idea come from the part of the sentence preceding the phrase in Question 14.

15. B. The words that the narrator says aloud are placed in quotation marks and the given phrase isn’t punctuated that way, so Choice (A) can’t be correct. After all, you can’t reassure someone without words. Choices (C), (D), and (E) aren’t even in the running, as the passage supplies no evidence for these answers. Choice (B) draws upon a childlike habit: You tell yourself that everything will be okay, and then you tell yourself again (and maybe again!) to convince yourself that everything will be okay. So repeat after me: I will ace the SAT. I will.

16. D. Lines 90–100 describe the time period just before the narrator leaves for Spain. Most of the paragraph focuses on the future (“I want them to go away so I can begin” — Lines 93–94). When popcorn pops, a hard kernel changes into a tasty snack. The narrator is ready to change — to go abroad — and to start a new life; Choice (D) expresses this message.

17. A. By definition, islands are cut off from the mainland. The narrator’s “in the middle of the living room” (the island) and sitting “on the floor” (Line 3) instead of on the sofa or a chair (the discomfort).

18. E. The narrator doesn’t “turn around” (Lines 98–99), but she knows that her family is shrinking. She’s not talking about art lessons — Choice (A). Instead, she’s describing her relationship to her family. She says that she’s “laboring to leave, not enter, the family” (Line 97). Leaving the family diminishes their influence over her, an idea expressed in Choice (E).

19. B. Throughout the passage, the narrator sprinkles little hints that all is not well. Her leaving “at least for [her] mother” (Line 19) is difficult, but what about the other two family members mentioned? The narrator says, “I’m getting out” (Line 42), the sort of comment you’d expect from a prisoner. Her rebellion when her mother suggests French also displays conflict. Choice (B) fits this level of unease better than either (C) or (E), which are more extreme choices. After all, the narrator cries (Line 81) and hugs (Line 94).

Section 8: Mathematics

1. C. The largest that k could be is 7, and 2(7) – 1 = 13.

2. C. Yes, you could just add up all the odd numbers from 3 to 11, but it’s easier to take them in pairs: 3 plus 11 is 14, and so is 5 + 9. That’s two 14s, which is 28; now you just have to include 7, which makes a total of 35.

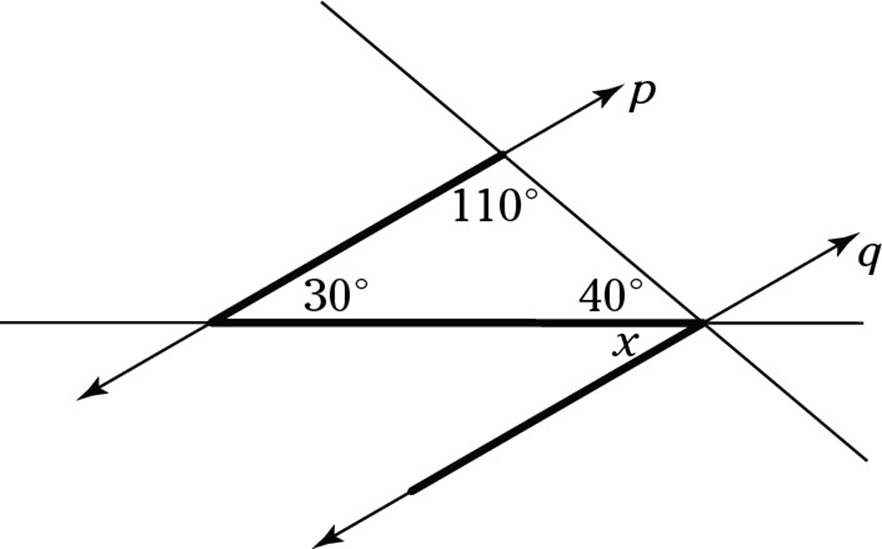

3. A. Because 110° and 40° are two angles of a triangle, the sum of the three angles has to be 180°, which means the third angle must be 30°. The third angle makes a Z with x, and, because the original lines are parallel, these angles are congruent. (Officially, the 30° angle in the triangle and x are alternate interior angles.)

4. B. Because the two numbers are directly proportional, you can set up a proportion:

![]() . Doing that wacky cross-multiplying thing gives you 10x = 90, so x = $9.00. (For

. Doing that wacky cross-multiplying thing gives you 10x = 90, so x = $9.00. (For

more information on proportions, check out Chapter 12.)

5. D. This one isn’t too tough if you’re careful with the negative signs: (–2)2 – 3(–4) = 4 + 12 = 16.

6. C. Don’t plug in 25 for x; you want the whole function to equal 25. So, ![]() , and

, and ![]() must equal 4. Therefore,

must equal 4. Therefore, ![]() equals 9, which is true when x = 81.

equals 9, which is true when x = 81.

7. B. The figure contains 12 squares, so each one has an area of 48 ÷ 12 = 4 and, thus, each side has a length of 2. Because AB covers 5 sides, its length is 10.

8. E. Yes, this one is a trick question. If (like me) you think fractions are cool, you solved this question this way: 1⁄4 goes to the first child, which leaves 3⁄4. One-third of that equals 1⁄3 × 3⁄4 = 1⁄4, so 1⁄4 goes to the second child, too, with 1⁄2 of the candy still left. Because the third child takes half of the half that’s left, that’s another 1⁄4, and the fourth child gets the 1⁄4 that remains. Of course, you can also do this problem by picking a nice number (say, 100) and working it out that way, a method you might like better.

9. B. Because the whole circle has a diameter of 8, its radius is 4 and its area is πr2, or 16π. (Don’t fall into the common trap of squaring the diameter by accident.) Each smaller circle has half the radius of the large one, which is 2, so each one has an area of 4π. There you go: The shaded area is 16π – (2 × 4π) = 16π – 8π = 8π.

10. D. Performing this transformation doubles all the y-coordinates and then adds 4 to them, without changing the x-coordinates. Doing so with each of the five points on the original graph gives you (–1, 4), (0, –2), (1, –4), (2, –2), and (3, 4). Only Choice (D) is in the list.

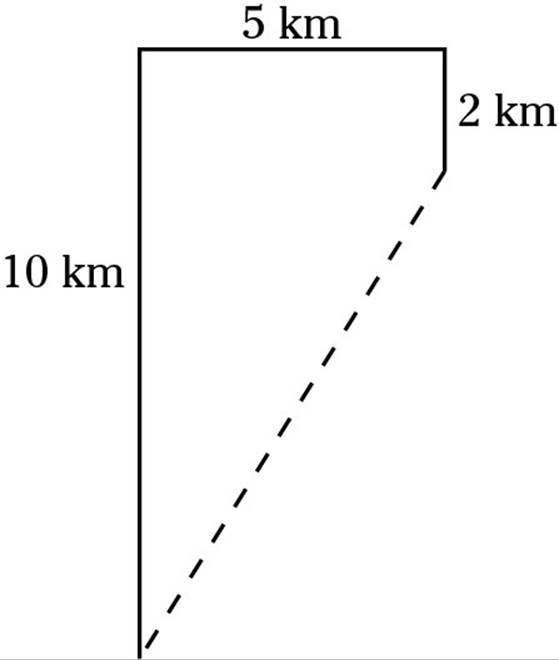

11. C. As is often the case, drawing a diagram like this one can help you solve this problem:

The dotted line shows the student’s distance from home, which is the hypotenuse of a right triangle with legs 5 and 8 (from 10 – 2). That ol’ Pythagorean Theorem tells you that ![]() .

.

12. A. Ah, yes, an old trap from my algebra classes. To solve this problem, you can use a formula I explain in Chapter 14: (a + b)2 = (a + b)(a + b) = a2 + 2ab + b2. I’d memorize that formula, if I were you. But, if your memory freezes, just use the FOIL method by writing (x – 5)(x – 5). Now follow the FOIL steps. Multiply the first terms (x · x = x2). Now multiply the outer terms (x · –5 = –5x). Next, multiply the inner terms (–5 · x = –5x). Now multiply the last terms (–5 × –5 = 25). Combine the results, and you end up with Choice (A).

Check out Chapter 14 for more details about factoring and using the FOIL method.

Check out Chapter 14 for more details about factoring and using the FOIL method.

13. D. You know that 5~7 equals 10 because b > a, and you’re told to add 3 to b when that happens. Also, 7~8 equals 11 for the same reason. Moving on, 7~7 equals 5 because a = b. And 7~5 equals 2 × 7, which is 14, because a > b. You have your answer, but checking the last one just for safety tells you that 11~7 equals 2 × 11, which is 22.

14. A. To solve this problem, I’ll pick pretty numbers and say that 10 widgets makes a thingumajig and that a thingumajig can produce 2 whatchamacallits. So it takes 5 widgets, or x⁄y, to make one whatchamacallit. To make n whatchamacallits, you have to multiply by n, which is what Choice (A) tells you to do.

15. D. The 12 cards have a total of 24 sides, and symbols A and B represent 13 of them. Because you want C to show up as much as possible, the easiest way to do so is to have only As and Bs on 6 cards (12 sides), with one more on a side of another card. Now you can put a C on the other side of that card and another C on some other card. You’ve taken care of the rule that each symbol must appear on at least two cards, and you’ve used a total of 8 cards. Thus, you’re left with a maximum of 4 cards that could be all Ds.

16. C. Because you know QR, your goal is to find either RS or PQ. Now, PS must be the same as QR, so PS = 7 and the Pythagorean Theorem tells you that ![]() . The next key step is to realize that triangles APS and DSR are similar, because angles A and D are both right angles, while APS and DSP are also congruent. Thus, triangle DSR is exactly three times as big as triangle APS, so SR is just three times bigger than PS, and SR = 21. Finally, the area of PQRS is 7 × 21 = 147.

. The next key step is to realize that triangles APS and DSR are similar, because angles A and D are both right angles, while APS and DSP are also congruent. Thus, triangle DSR is exactly three times as big as triangle APS, so SR is just three times bigger than PS, and SR = 21. Finally, the area of PQRS is 7 × 21 = 147.

Section 9: Multiple-Choice Writing

1. C. Got a watch? This sentence is mostly about timing. Only two choices, (A) and (C), are serious contenders. The word immediately tells you that the two actions in the sentence (hearing about the chariot and claiming ownership) took place more or less at the same time. Choice (A) is wrong because it places the hearing before the unearthing. Choice (C), on the other hand, expresses a simultaneous situation. Therefore, (C) is the right answer.

2. E. In the question’s original sentence, explore is in present tense and the second verb, included, shifts to past tense. As you may recall from past grammar lessons, you should never change tense unnecessarily in a sentence. Thus, you know Choice (E) is the winner because it aligns the second verb with the first by changing included to includes.

3. A. Sometimes I feel sorry for nor. It’s a perfectly respectable conjunction (a word that joins equal elements of a sentence), but people tend to ignore it in favor of and, but, and or — also conjunctions. The sentence is correct as written because nor links two complete thoughts. Did Choice (B) fool you? It’s wrong because you don’t need a semicolon to join the sentences because nor has already done the job.

4. B. Were intended is the main verb in the sentence, but if you stop there, the thought is incomplete. An infinitive, the to-plus-a-verb form, generally follows the main verb. Two choices, (B) and (E), supply an infinitive, but (E) throws in the unnecessary pronoun they.

5. B. Short and sweet works here. The underlined portion of the sentence is the definition of desks. “Their cloth kilts stretched tightly across their knees” is all you need for that definition. Case closed.

6. C. About a gazillion years ago, English teachers decided that every sentence must express a complete thought. The original sentence in Question 6 doesn’t, because which appear to start slowly leaves you hanging. The pronoun which generally begins a description, and when a whichstatement follows a subject, it usually interrupts the subject/verb pair. In the original sentence, you have no subject/verb pair. Choice (C) creates a subject/verb pair, projects appear, and turns a fragment into a complete thought.

7. D. When you see a list in a sentence, everything in it should have the same grammatical identity. The original sentence lists three things: “is good at detail,” “calm during interactions with customers,” and “knows about the devices the company sells.” The first and third items begin with verbs, but the second item begins with an adjective. Choice (D) adds a verb, so you’re all set.

8. B. In the original sentence, the pronoun it refers to a whole bunch of words — everything that precedes the comma. Problem! A pronoun can’t substitute for any expression containing a subject/verb combo. Choice (B) takes care of the problem by dumping the pronoun. Choice (C) is close but has two flaws: When you’re presenting two alternatives, whether is better than if. Also, you don’t need a comma after the word danger. Choice (D) is clumsy, and (E) is illogical because controversially, a description, has nothing to describe.

9. A. Logic tells you that Eleanor is fluent now because of something that happened before now. Having learned, the descriptive verb form in Choice (A), places the learning before the fluency — exactly what you want. Choice (D) begins with a descriptive verb form, too, and the past tense places it before the fluency. However, (D) is wordy, and (A) is concise. No doubt about it: (A) is better.

10. E. The sentence (which, by the way, describes a scene I actually witnessed), implies cause and effect. The philosopher is discussing lofty ideas and ignoring little details like walls. Choice (E) has cause and effect built into it with the so . . . that pair, making (E) the right answer.

11. C. Not only pairs with but also to join together similar things. In the original sentence, you have the noun symbol right after not only. But after the conjunction but, you have the subject/verb pair it also attracts. Choice (C) solves the problem by placing the noun tourist attractionafter the second conjunction. Now the conjunction pair links nouns and their descriptors.

12. E. The answer choices fiddle with several verb tenses, but this question actually presents a description problem. Who’s viewing the elephants, lions, and tigers? In the original sentence, the sea lions are viewing them, because a verb statement at the beginning of a sentence automatically attaches itself to the subject of the sentence. Only Choices (D) and (E) insert viewers. Choice (D) doesn’t make the grade because person is singular and them is plural. Choice (E) solves the description problem nicely.

13. C. Sometimes simplest is best, and this sentence is one of those times. If you’ve got exotic and common, the reader already knows that the park has variety.

14. A. This sentence contrasts what tourists like and what artists do. Although generally presents a condition and explains what happened despite that condition. The original sentence expresses that idea perfectly.

Answer Key for Practice Exam 3

Section 2

1. E

2. C

3. A

4. D

5. B

6. E

7. A

8. C

9. C

10. E

11. A

12. D

13. D

14. A

15. C

16. E

17. A

18. B

19. A

20. C

21. D

22. A

23. D

24. C

Section 3

1. C

2. E

3. A

4. D

5. B

6. D

7. B

8. B

9. 100

10. 4

11. 144

12. 170

13. 400

14. 16

15. 12

16. 60

17. 27

18. 400

Section 4

1. D

2. B

3. E

4. C

5. A

6. C

7. A

8. D

9. B

10. D

11. A

12. B

13. D

14. E

15. A

16. B

17. D

18. E

19. C

20. A

21. E

22. C

23. B

24. D

Section 5

1. A

2. E

3. D

4. B

5. B

6. B

7. C

8. A

9. D

10. B

11. C

12. A

13. C

14. D

15. B

16. B

17. A

18. E

19. A

20. B

Section 6

1. C

2. E

3. D

4. D

5. B

6. A

7. D

8. C

9. D

10. B

11. A

12. D

13. E

14. B

15. D

16. B

17. A

18. A

19. B

20. B

21. B

22. D

23. E

24. C

25. D

26. D

27. C

28. B

29. B

30. C

31. A

32. E

33. B

34. C

35. D

Section 7

1. A

2. C

3. B

4. E

5. B

6. B

7. A

8. D

9. E

10. C

11. B

12. C

13. A

14. C

15. B

16. D

17. A

18. E

19. B

Section 8

1. C

2. C

3. A

4. B

5. D

6. C

7. B

8. E

9. B

10. D

11. C

12. A

13. D

14. A

15. D

16. C

Section 9

1. C

2. E

3. A

4. B

5. B

6. C

7. D

8. B

9. A

10. E

11. C

12. E

13. C

14. A