SAT 2016

CHAPTER 6

THE SAT ESSAY: ANALYZING ARGUMENTS

1. Understand the Analytical Task

2. Use the “Three-Pass Approach”

3. Organize Your Thoughts

4. Write the Essay

Sample Essay

The SAT Essay

What is the SAT Essay?

The SAT includes an optional 50-minute Essay assignment designed to assess your

proficiency in writing a cogent and clear analysis of a challenging rhetorical essay written for a broad audience.

Should you choose to accept the challenge, the SAT Essay will be the fifth and final section of your test.

The SAT Essay assignment asks you to read a 650–750 word rhetorical essay (such as a New York Times op-ed about the economic pros and cons of using biofuels) and to write a well-organized response that

• demonstrates an understanding of the essay”s central ideas and important details

• analyzes its use of evidence, such as facts or examples, to support its claims

• critiques its use of reasoning to develop ideas to connect claims and evidence

• examines how it uses stylistic or persuasive elements, such as word choice or appeals to emotion, to add power to the ideas expressed

How is it used?

Many colleges use the SAT Essay in admissions or placement decisions. Many also regard it as an important indicator of essential skills for success in college, specifically, your ability to demonstrate understanding of complex reading assignments, to analyze arguments, and to express your thoughts in writing.

Sound intimidating? It”s not.

If you have mastered the analytical reading skills discussed in Chapter 5, you already have a strong start on tackling the SAT Essay, since strong active reading of the source text is the first and most important step in the analytical writing task. There are four rules to success on the SAT Essay, and the 13 lessons in this chapter will give you the knowledge and practice you need to master all of them.

Understand the Analytical Task

Lesson 1: Fifty minutes

The SAT Essay assesses your proficiency in reading, analysis, and writing. You are given 50 minutes to read an argumentative essay and write an analysis that demonstrates your comprehension of the essay”s primary and secondary ideas and your understanding of its use of evidence, language, reasoning, and rhetorical or literary elements to support those ideas. You must support your claims with evidence from the text and use critical reasoning to evaluate its rhetorical effectiveness.

So what should you do with those 50 minutes?

Reading: 15–20 minutes

Although 15–20 minutes may seem like a long time to devote to reading a 750-word essay, remember that you must do more than simply read the essay. You must comprehend, analyze, and critique it. In other words, you must master the “Three-Pass Approach” that we will practice in lessons 4–6. This is a fairly advanced reading technique, and you will need to devote substantial time to practicing it. Even once you”ve mastered it, you will still need to set aside 15–20 minutes on the SAT Essay section to read and annotate the passage thoroughly.

Organizing: 10–15 minutes

Your next task is to gather the ideas from your analyses and use them to formulate a thesis and structure for a five- or six-paragraph essay. If you have performed your first task properly and have completed your “Three-Pass” analysis, creating an outline will be much easier. We will discuss these tasks in lessons 7 and 8.

Your thesis should summarize the thesis of the essay and its secondary ideas, describe the author”s main stylistic and rhetorical elements, and provide an insightful critique of the essay.

Take your time with this process, too. Don”t make the mistake of writing your essay before you have articulated a thoughtful guiding question and outlined the essay as a whole.

Writing: 20–25 minutes

Next, of course, you have to write your easy. To get a high score, your essay must provide an eloquent introduction and conclusion, articulate a precise central claim about the essay, be well organized, show a logical and cohesive progression of ideas, maintain a formal style and an objective tone, and show a strong command of language. But if you”ve followed these steps, which we will explore in more detail below, the essay will flow naturally and easily from your analysis and outline.

Lesson 2: Learn the format of the SAT Essay

The passages you are asked to analyze present a point of view on a topic in the arts, sciences, politics, or culture. They address a broad audience, express nuanced views on complex subjects, and use evidence and logical reasoning to support their claims.

The Essay, should you choose to take it, is the fifth and final portion of the SAT. Here is a sample essay and prompt (from the diagnostic test in Chapter 2). Read it carefully to familiarize yourself with the instructions and format.

You have 50 minutes to read the passage and write an essay in response to the prompt provided below.

As you read the passage below, consider how Steven Pinker uses

• evidence, such as facts or examples, to support his claims

• reasoning to develop ideas and connect claims and evidence

• stylistic or persuasive elements, such as word choice or appeals to emotion, to add power to the ideas expressed

Adapted from Steven Pinker, “Mind Over Mass Media.” ©2010 by The New York Times. Originally published June 10, 2010.

New forms of media have always caused moral panics: the printing press, newspapers, paperbacks and television were all once denounced as threats to their consumers” brainpower and moral fiber.

So too with electronic technologies. PowerPoint, we”re told, is reducing discourse to bullet points. Search engines lower our intelligence, encouraging us to skim on the surface of knowledge rather than dive to its depths. Twitter is shrinking our attention spans.

But such panics often fail reality checks. When comic books were accused of turning juveniles into delinquents in the 1950s, crime was falling to record lows, just as the denunciations of video games in the 1990s coincided with the great American crime decline. The decades of television, transistor radios and rock videos were also decades in which I.Q. scores rose continuously.

For a reality check today, take the state of science, which demands high levels of brainwork and is measured by clear benchmarks of discovery. Today, scientists are never far from their e-mail and cannot lecture without PowerPoint. If electronic media were hazardous to intelligence, the quality of science would be plummeting. Yet discoveries are multiplying like fruit flies, and progress is dizzying. Other activities in the life of the mind, like philosophy, history and cultural criticism, are likewise flourishing.

Critics of new media sometimes use science itself to press their case, citing research that shows how “experience can change the brain.” But cognitive neuroscientists roll their eyes at such talk. Yes, every time we learn a fact or skill the wiring of the brain changes; it”s not as if the information is stored in the pancreas. But the existence of neural plasticity does not mean the brain is a blob of clay pounded into shape by experience.

Experience does not revamp the basic information-processing capacities of the brain. Speed-reading programs have long claimed to do just that, but the verdict was rendered by Woody Allen after he read War and Peace in one sitting: “It was about Russia.” Genuine multitasking, too, has been exposed as a myth, not just by laboratory studies but by the familiar sight of an SUV undulating between lanes as the driver cuts deals on his cell phone.

Moreover, the evidence indicates that the effects of experience are highly specific to the experiences themselves. If you train people to do one thing, they get better at doing that thing, but almost nothing else. Music doesn”t make you better at math; conjugating Latin doesn”t make you more logical; brain-training games don”t make you smarter. Accomplished people don”t bulk up their brains with intellectual calisthenics; they immerse themselves in their fields. Novelists read lots of novels; scientists read lots of science.

The effects of consuming electronic media are also likely to be far more limited than the panic implies. Media critics write as if the brain takes on the qualities of whatever it consumes, the informational equivalent of “you are what you eat.” As with primitive peoples who believe that eating fierce animals will make them fierce, they assume that watching quick cuts in rock videos turns your mental life into quick cuts or that reading bullet points and Twitter postings turns your thoughts into bullet points and Twitter postings.

Yes, the constant arrival of information packets can be distracting or addictive, especially to people with attention deficit disorder. But distraction is not a new phenomenon. The solution is not to bemoan technology but to develop strategies of self-control, as we do with every other temptation in life. Turn off e-mail or Twitter when you work, put away your BlackBerry at dinner time, ask your spouse to call you to bed at a designated hour.

And to encourage intellectual depth, don”t rail at PowerPoint or Google. It”s not as if habits of deep reflection, thorough research and rigorous reasoning ever came naturally to people. They must be acquired in special institutions, which we call universities, and maintained with constant upkeep, which we call analysis, criticism and debate. They are not granted by propping a heavy encyclopedia on your lap, nor are they taken away by efficient access to information on the Internet.

The new media have caught on for a reason. Knowledge is increasing exponentially; human brainpower and waking hours are not. Fortunately, the Internet and information technologies are helping us manage, search, and retrieve our collective intellectual output at different scales, from Twitter and previews to e-books and online encyclopedias. Far from making us stupid, these technologies are the only things that will keep us smart.

Write an essay in which you explain how Steven Pinker builds an argument to persuade his audience that new media are not destroying our moral and intellectual abilities. In your essay, analyze how Pinker uses one or more of the features listed in the box above (or features of your own choice) to strengthen the logic and persuasiveness of his argument. Be sure that your analysis focuses on the most relevant features of the passage.

Your essay should NOT explain whether you agree with Pinker”s claims, but rather explain how Pinker builds an argument to persuade his audience.

Lesson 3: Understand the scoring rubric

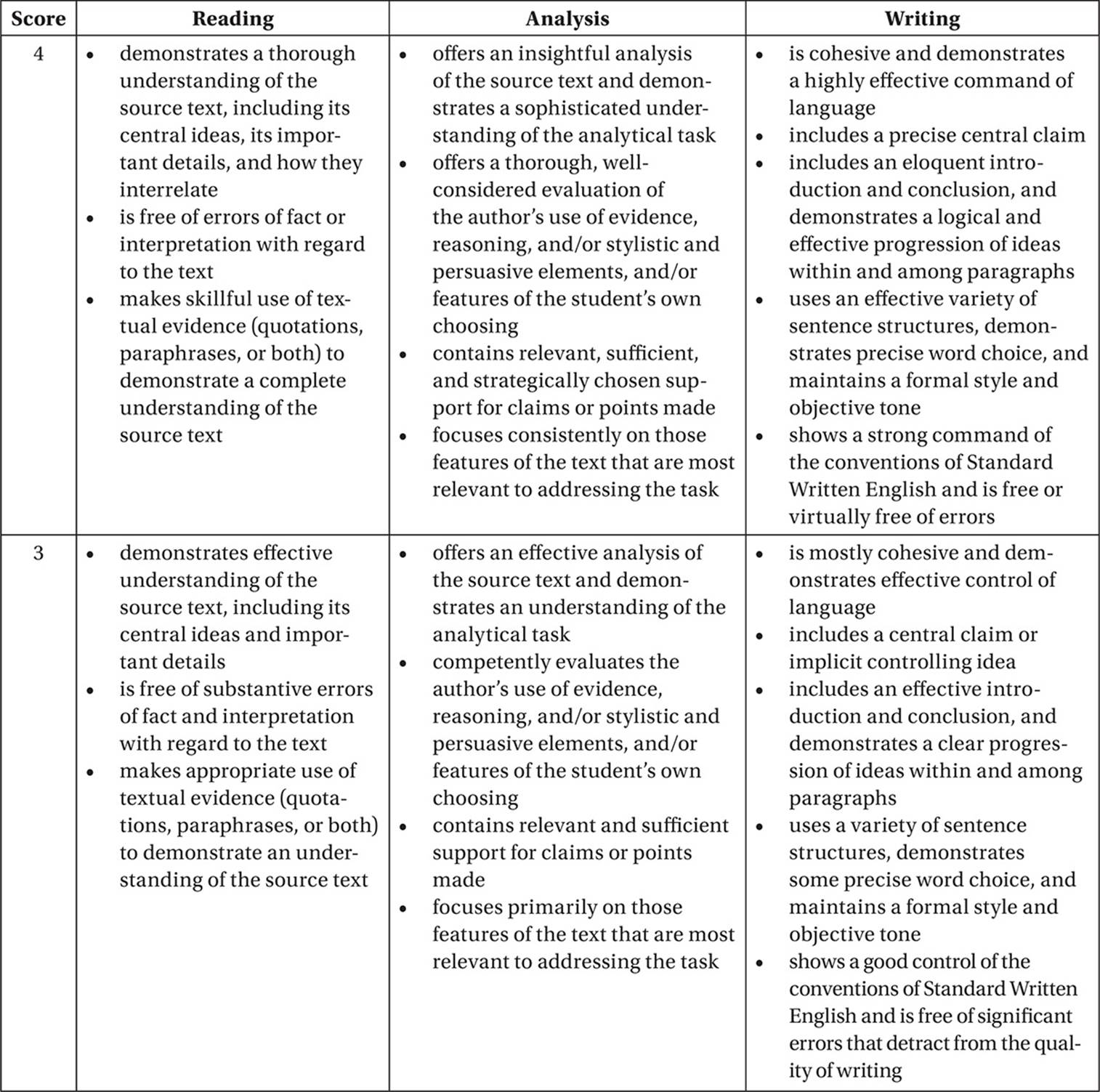

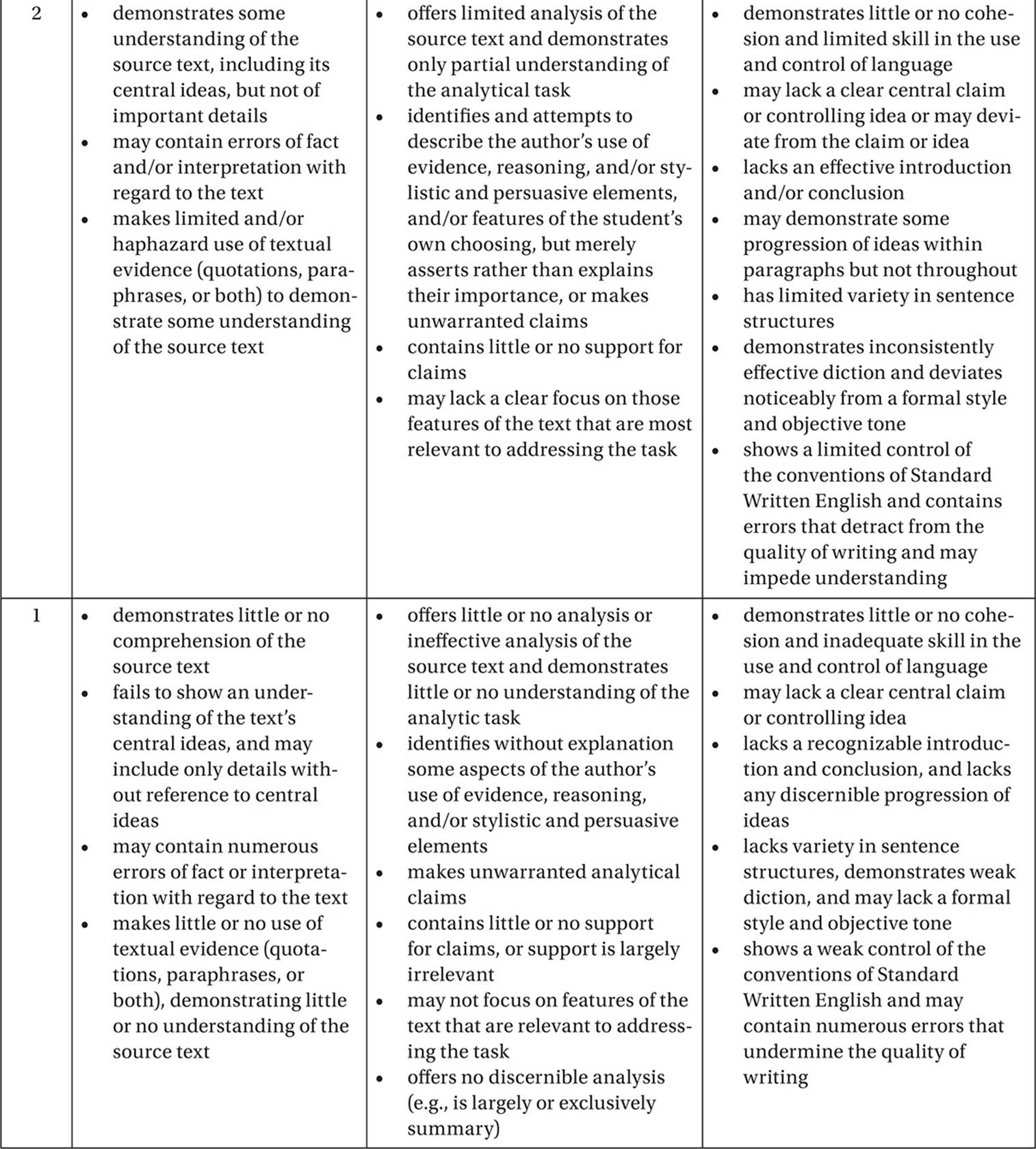

Your essay will be scored based on three criteria: reading, analysis, and writing. Two trained readers will give your essay a score of 1 to 4 on these three criteria, and your subscore for each criterion will be the sum of these two, that is, a score from 2 to 8. Here is the official rubric for all three criteria.

SAT Essay Scoring Rubric