LSAT 2016

PART I All About the LSAT

CHAPTER 5 LSAT Reading Comprehension

In this chapter, you will learn:

![]() The importance of retrieval, not recall, in the Reading Comprehension section

The importance of retrieval, not recall, in the Reading Comprehension section

![]() How to apply annotative-reading techniques to the passages

How to apply annotative-reading techniques to the passages

![]() The six different types of questions you will encounter and techniques for working each one

The six different types of questions you will encounter and techniques for working each one

![]() How to approach the comparative reading passage

How to approach the comparative reading passage

![]() How to approach the Reading Comprehension section as a whole

How to approach the Reading Comprehension section as a whole

As noted in Chapter 1, each Reading Comprehension section contains four passages (one of which, the comparative reading passage, is actually a pair of two shorter passages). There will be one passage from each of the following general content areas: law, science, the arts, and social science/humanities. Examples of specific topics that you might encounter include:

![]() Law: international law, intellectual property, legal theory, legal history, courtroom practice

Law: international law, intellectual property, legal theory, legal history, courtroom practice

![]() Science: geology, botany, computer science, evolutionary biology, ecology, engineering, mathematics, animal behavior

Science: geology, botany, computer science, evolutionary biology, ecology, engineering, mathematics, animal behavior

![]() The arts: literature, painting, dance, theater, sculpture, music, film, poetry

The arts: literature, painting, dance, theater, sculpture, music, film, poetry

![]() Social science/humanities: economics, anthropology, history, urban planning, linguistics, archaeology, philosophy, psychology

Social science/humanities: economics, anthropology, history, urban planning, linguistics, archaeology, philosophy, psychology

The Reading Comprehension section is an open-book test; the correct answer to every question must be directly supported by the text of the passage. This chapter lays out a strategy that is designed to take advantage of that fact. That strategy requires you to take a particular approach both to reading the passage and to answering the questions. The first two cases in this chapter concentrate on reading. They introduce annotative reading, a technique that has been designed especially for the Reading Comprehension section of the LSAT. You’ll learn how to annotate the passage as you read it in a way that positions you to answer the questions quickly and with a high rate of accuracy.

Cases 3 through 8 introduce the six major types of questions you’ll encounter, while Case 9 discusses question types that are unique to the Comparative Reading passage.

You’ll use a three-step method in the Reading Comprehension section:

1. Read the question and identify your task.

2. Go back to the passage to find the answer.

3. Read every word of every answer choice.

The cases will demonstrate how this method should be applied to each major question type. As in the previous two chapters, the last case discusses section-wide strategy.

Three final notes before turning to the first case. First, you’ll be learning a particular, specialized way of reading that you probably haven’t employed before. You may start off reading slowly. That’s OK. With practice, you’ll get faster at employing the annotative-reading techniques, and eventually you’ll be able to work at a pace that is compatible with the Reading Comprehension section’s 35-minute time constraint. In the early stages of your study, take the time to apply the techniques correctly, even if it takes you a long time to do so. Practice only helps if you’re building good habits.

Second, as you work the practice Reading Comprehension passages and sections in this book, keep a log of the questions you miss and relevant details about each question. We all have different strengths and weaknesses as readers. You won’t be able to identify the areas in which you need improvement unless you’ve been tracking your performance. A sample performance log might look like this:

After you’ve worked through a few passages, look for trends among the questions you’re missing. This will help you focus your studying efforts. It may also be helpful to you as you’re developing your strategy for tackling the section as a whole; Case 10 will explore this possibility in greater detail.

Finally, much of the Reading Comprehension section’s difficulty stems from the fact that you’re probably unaccustomed to reading texts with the particular combination of length, density, and subject matter that you encounter on the LSAT. The more comfortable you can become reading this kind of material, the better you’ll fare on test day. Working practice questions is not the only way you can increase your comfort level. The articles in the weekly newsmagazine The Economist tend to be somewhat similar to the passages on the LSAT in their length, tone, purpose, and content. Reading a few such articles each day is a good way to improve your reading skills.

Case 1

Retrieval, Not Recall: How to Read on the LSAT

This case introduces the annotative-reading method you will use to read the passages in the Reading Comprehension section. This case focuses on the “why” and “what” of annotative reading (the rationale for using this technique and the tasks it will help you accomplish), while Case 2 explains the “how” (the tools and techniques you will use to implement it).

You will read each passage with two aims in mind: (1) attaining an understanding of the passage’s main idea; and (2) mapping the location of the various details, evidence, and examples so that you can quickly locate and review them as you’re working the questions.

The Reading Comprehension Section as an Open-Book Test

If one of your professors gave you an open-book exam, would you bring your book and class notes into the exam room only to leave them facedown on your desk as you attempted to answer all the questions from memory? Of course not. You would double-check your answers to the exam’s questions against the information in the textbook and your notes.

The Reading Comprehension section gives you the same opportunity to verify the correctness of your responses. It is effectively an open-book test. And every right answer must be objectively, demonstrably correct based solely on the information in the text. Outside information, subjective judgments, and debatable inferences can play no role in determining the correctness of an answer. Imagine a person who takes the LSAT and, upon receiving a disappointing score, decides to sue the LSAC (with a test that’s administered to would-be future lawyers, the possibility is not as far-fetched as it sounds). “I’m absolutely certain,” the test taker argues, “that the answers I selected to the Reading Comprehension questions were right and that the answers you identified as correct were wrong.” If the judge were to ask one of the test writers, “Why is B the correct answer to question 5?” the test writer would have to be able to point to a specific portion of the passage and say, “This is the portion of the passage that makes B the correct answer.” There can’t be room for debate; it can’t be a matter of interpretation.

This is the mind-set with which the LSAC writes Reading Comprehension questions. As a test taker, your job is to exploit that mind-set. Getting a good score on the Reading Comprehension section doesn’t require you to undertake a sophisticated analysis of the passage. You don’t have to come up with insightful, original things to say about it. You don’t have to contemplate its broader significance or implications. All the right answers are right there on the page, in the passage.

How to Read the Passage with an Eye Toward Answering the Questions

Typically when you read, it’s either for pleasure or to learn—that is, to be able to retain and recall the information in the text. Obviously you’re not reading for pleasure on the LSAT. Nor are you reading for long-term recall; odds are you’ll happily forget everything about the passages roughly 30 seconds after you finish the section. What may be less obvious is that you’re also not reading for short-term recall either.

That’s the key point: you’re not reading for recall at all. You’re reading the passages on the Reading Comprehension section for one purpose: to correctly answer as many questions as possible in 35 minutes. And the best way to correctly answer as many questions as possible is to not rely on recall, but to go back to the passage and find the answer to every question you work.

And yet the most common mistake that test takers make on this section is trying to answer the questions from memory instead of going back to the passage to retrieve the answer. Not only is it a common mistake, but it’s also the mistake the test is most designed to exploit. The test writers know you’re working under time pressure and will be tempted to rely on your recall. The wrong answers are carefully worded to look like right answers to test takers who are working from memory.

The answers are in the passage. You just have to find them.

After you read each question, don’t try to remember the answer. Go find it. All of the techniques in the later cases are derived from this single idea. By far the single most important element of an effective Reading Comprehension strategy is being able to quickly find the answer to each question. And in order to do that, you need to develop a new style of reading, an LSAT-specific reading style.

You will read each passage from start to finish just once before working any questions, annotating the passage using “upfront reading” techniques. Your annotations will allow you to quickly find the answers to the questions when you go back to the passage for your question-specific reading.

Upfront Reading

If the Reading Comprehension section were untimed, it wouldn’t especially matter how you read the passage. You could pore over every word, taking as long as you needed to understand its content, purpose, and structure. In reality, you only have 35 minutes to work all four passages. This time constraint requires you to be productive, but also efficient.

Your upfront reading of the passage will be narrowly focused on accomplishing two tasks: articulating the main point of the passage as a whole and mapping the location of details, evidence, and examples.

Articulating the Main Point of the Passage as a Whole. The upfront reading is the only time you’ll read the passage straight through, from start to finish. It is your chance to step back and see the whole forest. With each question, you’ll study a particular tree. Almost all Reading Comprehension passages have at least one question that asks you to identify the passage’s main point, and having a clear handle on the main point is a helpful tool in answering many small-picture questions, too.

You should use your upfront reading to identify the passage’s main point and map the location of the various details.

Mapping the Location of Details, Evidence, and Examples. During your upfront reading your goal is not to carefully study and absorb all of the facts, examples, evidence, and other details that the passage discusses. Instead, you should use a system of annotations to simply map their locations, which will streamline your question-specific reading. Once marked for easy reference, you’ll be able to return to them quickly.

If you pore over the details during your upfront reading, you will inevitably have to rush or even abandon some of your question-specific readings and instead rely on your recall. Doing that plays right into the traps that the test writers have laid for you.

Plus, closely studying all the details upfront will surely cause you to waste valuable time. Suppose a passage supported its main point by offering four examples. If none of the questions asked you about example number two, any time you spent memorizing it would be for naught. Why read a portion of the passage closely if doing so won’t help you get a better score? The guideline is this: know exactly where the details are, not exactly what they say. You’ll spend your time wisely by letting the questions guide you.

Case 2 will introduce you to the customized annotation system to mark up the passage as you read it—the nuts and bolts of annotative reading.

Case 2

The Mechanics of Annotative Reading

During annotative reading, you’ll mark up the passage and make notes about its key points as you read. The primary benefit of annotative reading is that it enhances your focus and concentration. The passages on the Reading Comprehension section aren’t exactly page-turners. Annotating them as you read forces you to pay attention and remain an active, engaged reader. If you’re reading passively, it’s all too easy to come to the end of a paragraph only to realize that you spaced out and didn’t absorb anything you read. Time is of the essence; you can’t afford to read the same paragraph two or three times. Annotative reading gives you a series of tasks to perform, and you can’t perform them if you’re not paying attention.

The system of annotative reading described in this case is tailor-made for the Reading Comprehension section. While there is room for some flexibility in how it is implemented, two aspects of it are indispensible. Whatever system of annotation you ultimately adopt must incorporate both of these aspects.

First, you are looking for three specific kinds of information in the passage:

1. The main point of each paragraph

2. Words that indicate connections between the paragraphs and the big ideas of the passage

3. Key components of factual details

Those first two bits of information will help you zero in on the passage’s main point as a whole. Annotating the factual details will pay dividends when it comes time to answer the questions. Mark up the passage for this information and nothing else.

Second, you must use the same system of symbols, marks, or notations for everything. Otherwise, it’s too easy to zone out and start mindlessly underlining or circling. Plus, having different annotations for different types of information will make it easier for you to locate each type quickly as you’re working the questions.

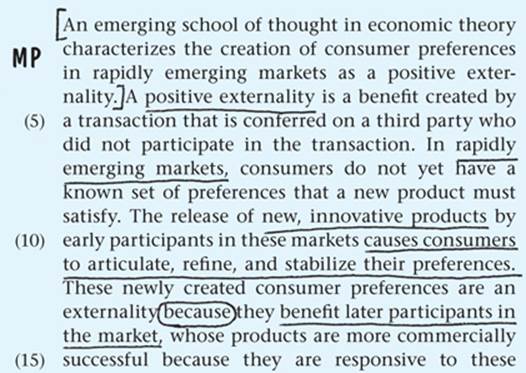

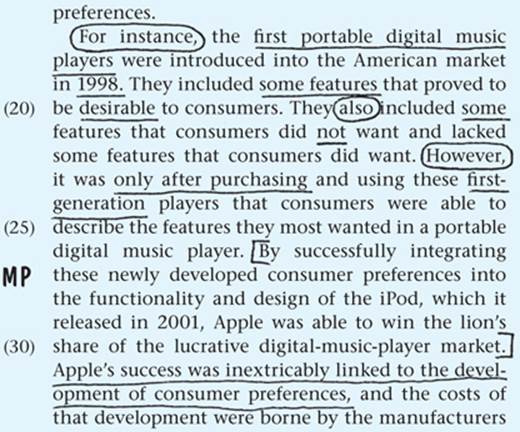

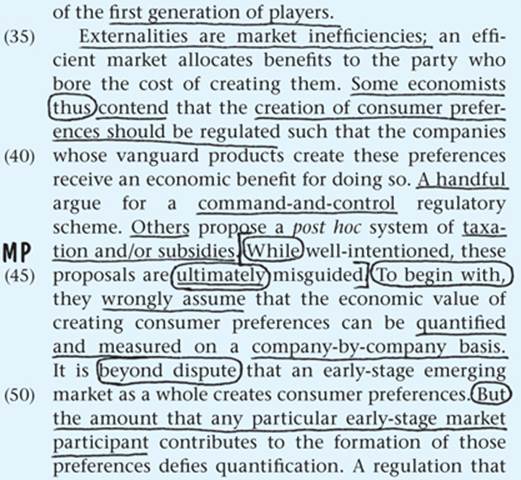

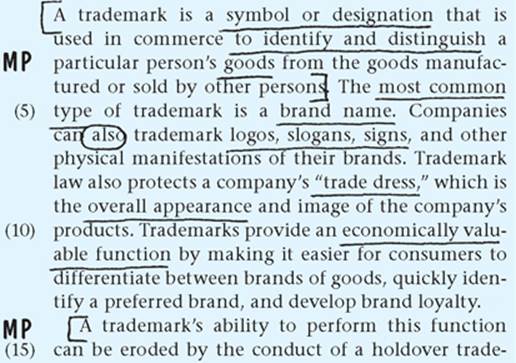

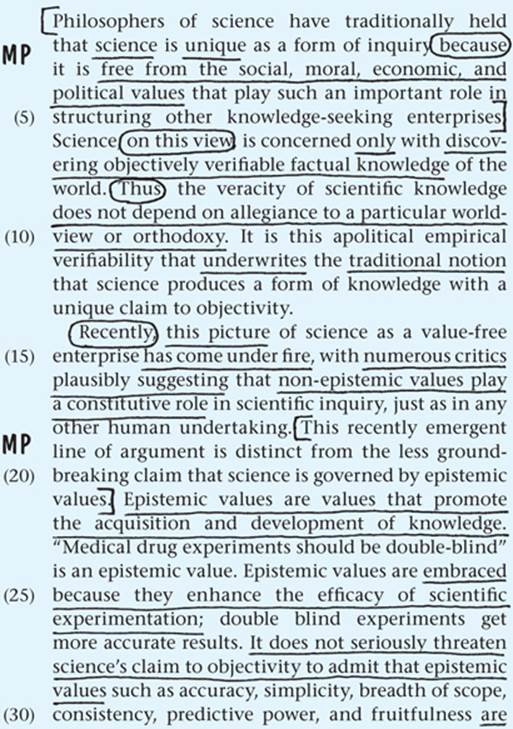

This case recommends that you put brackets around each paragraph’s main point, draw circles around words that indicate connections between the paragraphs, and underline the key snippets of factual detail. It also recommends making notes in the margins using the same letters or symbols. If you have a different system that works for you, feel free to use it, but do so consistently.

Understanding the Main Idea

Arriving at an understanding of the passage’s main point is a three-step process. First, as you read you’ll identify the main point of each paragraph. Second, you’ll identify the logical relationships between the main points of each paragraph. Third, when you’re done reading, you’ll summarize the passage by stringing together the main points of each paragraph. Summarizing the passage will help you home in on its main point.

Identify the Main Point of Each Paragraph. To identify the main point of each paragraph, you’ll draw on the skills you learned in Case 1 of Chapter 4, the discussion of Conclusion questions in the Arguments section. Each Argument contains background information, premises, and conclusions. The same is true of the Reading Comprehension passages; they’re basically just longer versions of that. This is also true of each paragraph within the passage. Zeroing in on each paragraph’s core idea is the first step toward identifying the main point of the passage as a whole.

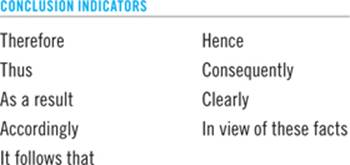

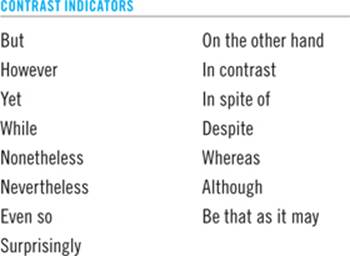

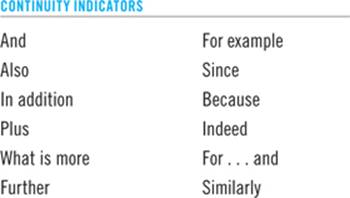

To identify the main point of a paragraph, use the same two techniques you learned in Chapter 4 for identifying the conclusion of an argument. First, keep an eye out for conclusion indicators, words whose function it is to introduce a conclusion. If you see one of the words listed below, circle it.

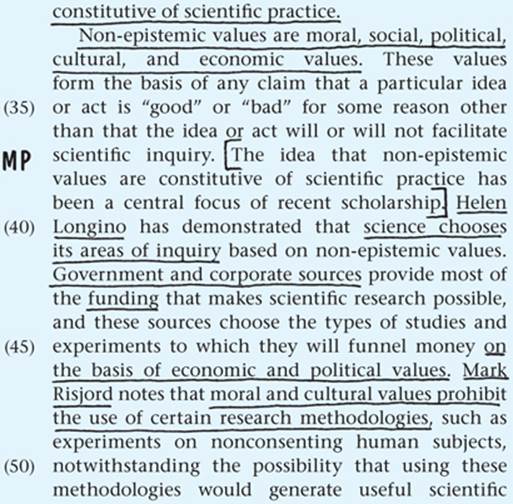

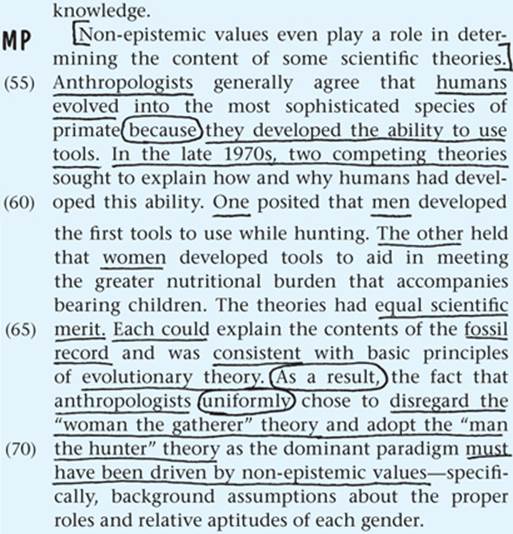

Second, the main point of the paragraph will typically use normative language (language that says something is “good” or “bad”) to express an opinion, evaluation, solution, proposal, explanation, assessment, or prediction. However, this is not always the case. Sometimes the purpose of an individual paragraph is to simply provide factual context, offer background information, or summarize a recent development. The main point of such a paragraph will simply be the fact that all of the other details fit under.

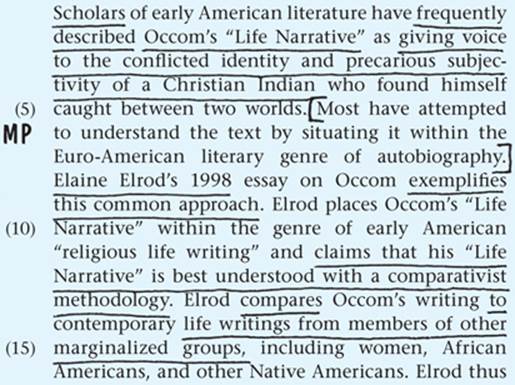

Once you’ve identified the main point of the paragraph, put brackets around the sentence, and make a note next to it in the margin. You can note “MP” for “main point,” “T” for “thesis,” or simply use an asterisk (*) to indicate importance. If you determine that the main point isn’t contained in any one sentence, you can either bracket the two sentences that it’s drawn from or jot a very brief summary of it in the margin. If you take this later tack, keep it short (three to five words); making extensive notes consumes a lot of time. You’ll repeat this process for every paragraph in the passage.

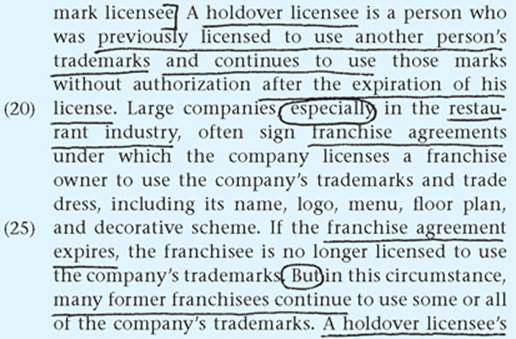

Circle the Connections Between Ideas. You’ll also look for words that indicate the connections between the ideas contained in each paragraph. For example, authors use certain words to indicate that what they are about to say will stand in contrast to what they just said. The following list offers some of the most common contrast indicators.

If you see these words or words like them, circle them. They indicate that the passage’s reasoning is changing direction.

Conversely, certain words indicate that an upcoming thought is consistent with and builds on the thought that preceded it. Circle these as well.

These words indicate that the passage’s argument is continuing along the same course.

Finally, circle any words of emphasis that communicate to the reader that a given portion of the passage is particularly significant to its overall argument.

Circling these words will remind you later that this was a point at which the passage built to one of its big ideas.

As noted above, understanding the passage’s main point requires you to be able to answer two questions: what does each paragraph say, and how do the paragraphs relate to each other? Bracketing the big-picture statements in each paragraph will help you answer the former question. Circling all of the indicator words will help you answer the latter.

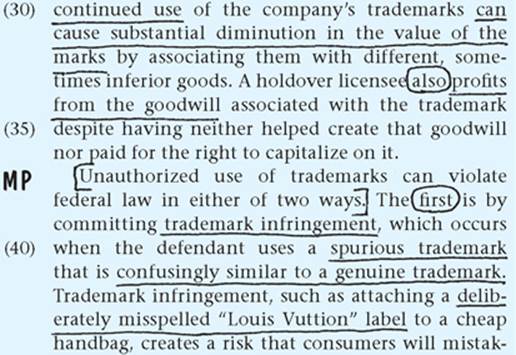

Summarize the Passage. Once you’ve finished reading, your focus shifts from the paragraph level to the passage level. The passage is nothing more than the sum of its parts. To understand the main point of the passage, you’ll figure out how the main points of its paragraphs fit together.

Start with the main points of the first two paragraphs. Is the second paragraph more of the same, or is it something different? Connect the two main points of each paragraph using a simple indicator word that captures their logical relationship, such as “and,” “because,” or “but.”

Once you’ve connected the main ideas of the first two paragraphs, repeat the process for each remaining paragraph. By doing so you’ll create a synopsis of the whole passage that encapsulates all of its key ideas and how they fit together.

Also keep a lookout for normative statements that are framed in sweeping, big-picture terms. Every so often, an author will come right out and state the main point of the passage in a single sentence. When you see language that looks like it’s trying to synthesize, reconcile, or explain a big idea, make sure you mark it. That language is likely one of the most important portions of the passage.

In the early stages of your Reading Comprehension practice, write out this summary using complete sentences. Doing so will help you build your reading and annotating skills, and it’s a good way to double-check your understanding of the passage. As you become more comfortable with the technique, use shorter summaries. Write down a few key words or phrases that capture each paragraph’s main idea. Given the 35-minute time limit, you won’t be able to write out full-sentence summaries of each paragraph on the day of the test. Instead, jot these shorter summaries in themargins beside each paragraph. Add an “and,” “but,” “because,” or other appropriate connector in the margin where the next paragraph begins. These shorthand summaries will help ensure that you don’t lose track of the passage’s big picture as you’re working through the questions.

Mapping the Location of the Details

When it comes to the details, your goal is to know exactly where they are, not exactly what they say. If one of the questions asks you about the work of a particular scholar, for example, you need to be able to scan the passage, find that scholar’s name, and review what the passage says about her work. By marking the location of key factual details, your annotation system will expedite this scan-and-retrieve process.

Underline the Key Facts. Specifically, you should underline the key portion of each discrete factual topic within the passage. As you read, mark:

![]() The names of people (scholars, researchers, authors, critics, etc.) whose work is discussed

The names of people (scholars, researchers, authors, critics, etc.) whose work is discussed

![]() The subject or findings of any experiments, studies, reports, illustrative examples, or other data

The subject or findings of any experiments, studies, reports, illustrative examples, or other data

![]() The names of key concepts, theories, techniques, or terms of art

The names of key concepts, theories, techniques, or terms of art

![]() Pluses and minuses, pros and cons, or strengths and weaknesses attributed to a proposal, theory, or explanation (these frequently appear in numbered lists)

Pluses and minuses, pros and cons, or strengths and weaknesses attributed to a proposal, theory, or explanation (these frequently appear in numbered lists)

Underline judiciously. Limit yourself to only the essential portion of each topic. Being disciplined about what you underline will force you to think critically about the text. Visually, you want to create a user-friendly map so that when you read a question and think, “Where did I read about that?” you can quickly glance back to the passage and find it. You won’t be able to do that if you’ve cluttered up the page by underlining half of the words in the passage.

In short, you want to use a “Goldilocks” amount of underlining. Mark just enough of the key terms, names, words, and phrases to jog your memory about each topic. But don’t mark so much that you can’t easily find what you’re looking for. It’s rarely helpful to underline an entire sentence. It’s never helpful to underline two entire sentences consecutively.

Putting Annotative Reading into Practice

Here’s a summary of your annotative-reading strategy:

1. Identify the main point of each paragraph.

![]() Be on the lookout for normative language.

Be on the lookout for normative language.

![]() Circle any conclusion indicators.

Circle any conclusion indicators.

![]() Once you’ve identified the main point, put brackets around it and make a note in the margin.

Once you’ve identified the main point, put brackets around it and make a note in the margin.

2. Determine the connections between paragraphs. Draw circles around contrast indicators, continuity indicators, and emphasis indicators.

3. Underline key factual details. Use a “Goldilocks” approach.

4. Summarize the passage’s contents by stating each paragraph’s main point and, where possible, connecting them with a conjunction that captures their logical relationship.

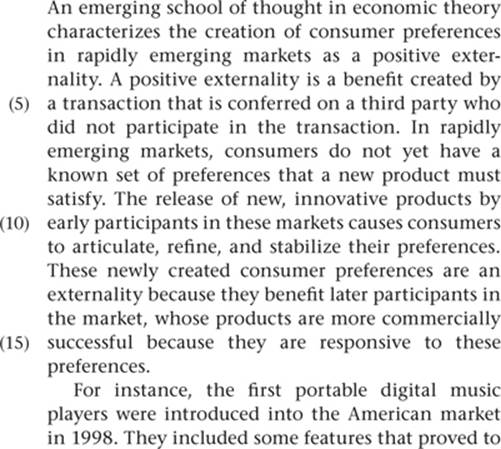

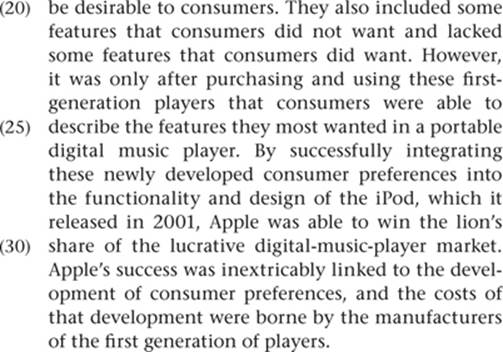

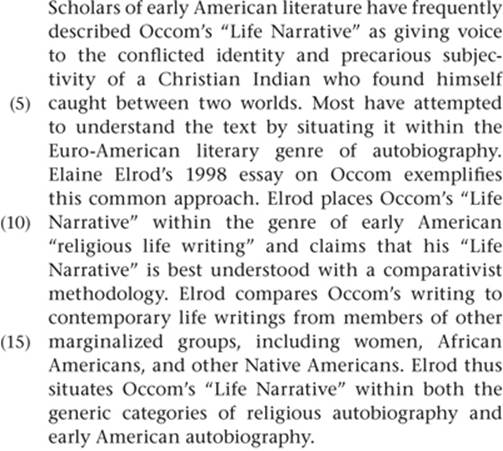

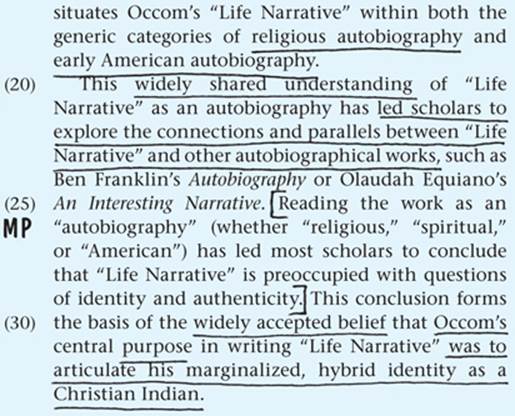

Practice

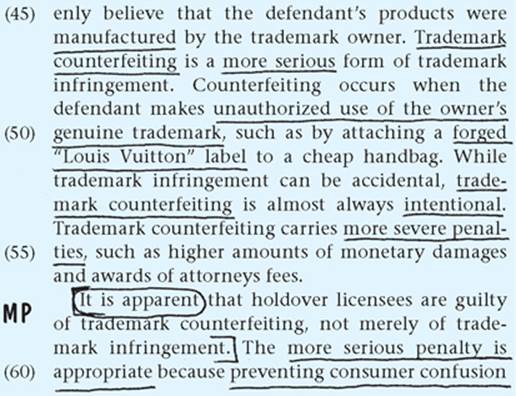

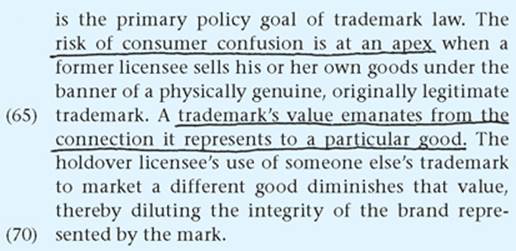

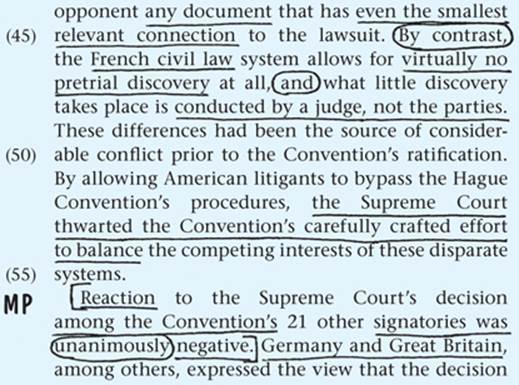

A sample passage follows. Read it and annotate it using the tools and techniques you’ve just learned. Don’t worry about how long it takes you to finish; take the time to do it right.

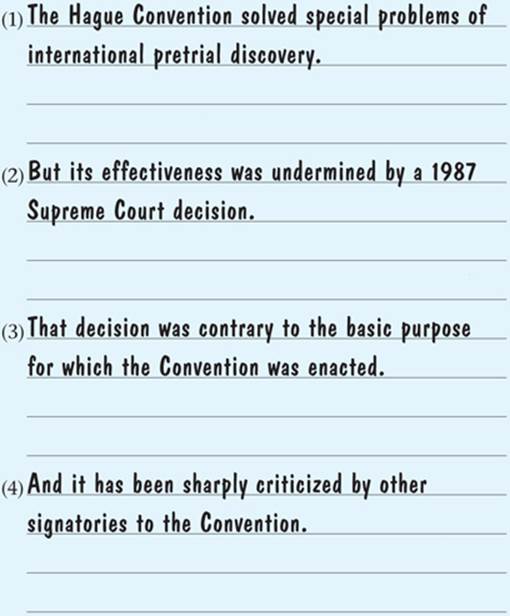

Before you continue reading, write down the main points of each of the passage’s four paragraphs in the space below. Connect them using a simple conjunction that captures the logical relationship between the ideas.

(1) ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

(2) ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

(3) ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

(4) ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

A sample annotation of this passage follows. Before you compare your annotation to that sample, review your work and ask yourself the following questions:

1. Have I used conclusion indicators and normative language to identify each paragraph’s main point?

2. Have I used contrast indicators, continuity indicators, and emphasis indicators to identify the logical relationship between each paragraph?

3. Have I created a summary of the passage that uses appropriate conjunctions to connect the main points of each paragraph?

4. Have I used a “Goldilocks” amount of underlining to highlight the key words and phrases that signal the location of the various factual details discussed in the passage?

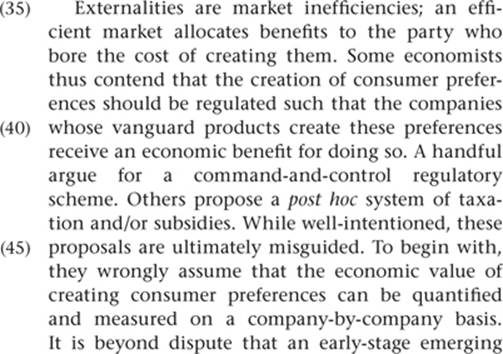

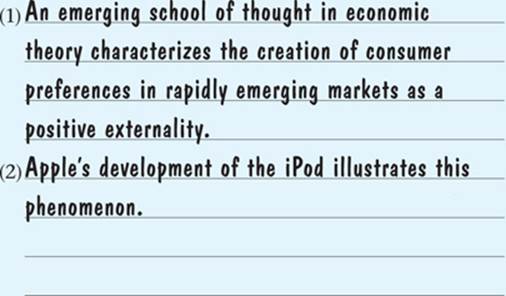

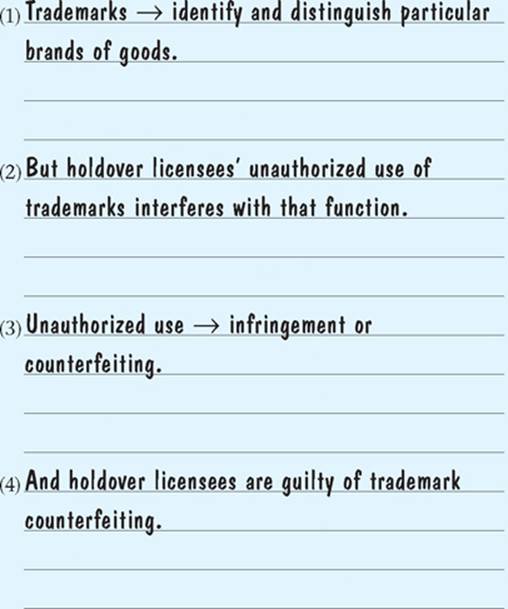

Your summary of the passage should look something like this:

The amount of text that is circled, bracketed, and underlined in this passage is a good indicator of about how much of the passage you should be marking up as you read. This passage also demonstrates the need to be flexible as you read. Notice there is more text underlined and circled in the last two paragraphs than there is in the first two paragraphs. That’s because the first two paragraphs are there to provide context and background information. The argument doesn’t really gain steam until paragraphs three and four.

If you had a hard time identifying each paragraph’s main point or deciding what to underline, don’t despair. Annotative reading takes practice. Each of the next eight cases includes a practice passage as well as sample annotations and summaries. Take the time to fully annotate and summarize each of these passages. Everything you do in the Reading Comprehension section begins with annotative reading.

Finally, it’s worth pointing out that this was not an easy passage to read. It was conceptually dense, featured a number of long sentences, and used a lot of technical terms. If it appeared on an LSAT, it would be one of the two more difficult passages in the section. In Case 10, we’ll discuss how to quickly rank the passages based on difficulty so that you’ll work the easier passages first. As you read and annotate the passages in the next eight cases, make notes to yourself about how difficult you find each passage and why. Those notes will help you put your section-wide strategy into practice.

A key component of that section-wide strategy is pacing. Case 10 will discuss in greater detail how you should pace yourself as you work the Reading Comprehension section. For now, all you need to know is that your goal is to eventually be able to complete your upfront reading of the passage—including making annotations and creating a summary—in somewhere between three and four minutes. In the early stages of your practice, don’t worry too much about timing. But as you become more comfortable with the techniques, keep track of how long it takes you to read and annotate each passage. Gradually accelerate the process so that you are moving toward a reading pace that you can employ on test day.

Case 3

Main Idea Questions

Main Idea questions, as the name suggests, require you to pick the answer choice that most accurately states the main point of the passage as a whole. Almost every passage in the Reading Comprehension section includes a Main Idea question. The annotative-reading strategy you learned in the previous case will help you answer these questions quickly and with a high rate of accuracy.

STEP 1: Read the Question and Identify Your Task

A Main Idea question will be worded in one of the following ways:

![]() Which of the following most accurately expresses the main point of the passage?

Which of the following most accurately expresses the main point of the passage?

![]() Which of the following most accurately summarizes the main idea of the passage?

Which of the following most accurately summarizes the main idea of the passage?

![]() The passage most helps to answer which one of the following questions?

The passage most helps to answer which one of the following questions?

STEP 2: Go Back to the Passage and Find the Answer

By creating a summary of the passage as part of your annotative-reading process, you’ve done the hard work of finding the answer to a Main Idea question. That said, it’s important to recognize that a summary is not the same thing as the main point. The main point of the passage is the core idea that it’s trying to persuade you of. The summary contains the main point, but it also contains background information and evidence or arguments offered in support of the main point.

STEP 3: Read Every Word of Every Answer Choice

The right answer to a Main Idea question will be the portion of your summary of the passage that embodies the key takeaway from the passage. The right answer will usually borrow or quote some language directly from the passage itself. Since Main Idea questions ask you about a big-picture concept, it can be tempting to go beyond what you’ve read and speculate about the passage’s significance or implications. As you work through the answer choices, keep in mind that the correct answer must be objectively, demonstrably correct based solely on the material in the passage.

COMMON TYPES OF WRONG ANSWERS

1. Too broad in scope. This is the most common type of wrong answer on Main Idea questions. Several of the incorrect answer choices are likely to go beyond the scope of the passage. They might discuss new information about a related topic. They might make a comparison between the topic of the passage and an outside topic that was not discussed in the passage. In particular, keep an eye out for the word only, which subtly makes the strongest possible comparative claim about the content of the passage.

2. Too narrow in scope. At least one of the wrong answers to a Main idea question is usually the main point of one paragraph. Such answer choices are designed to trick you, since they are focused on too small a portion of the passage.

3. In the right direction, but too strong. Finally, some wrong answers to Main Idea questions will express an idea that is similar to the one expressed in the passage but that is stated in overblown, amplified terms. The passages are excerpted from academic writing; they are cautious and precise. Watch out for answers that take the basic point of the passage and state it a little too categorically or forcefully.

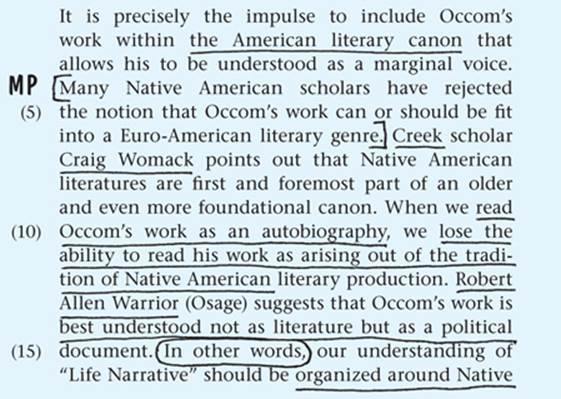

Practice

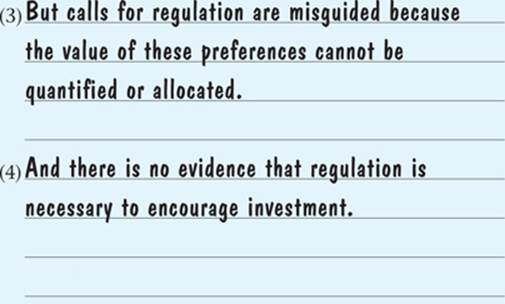

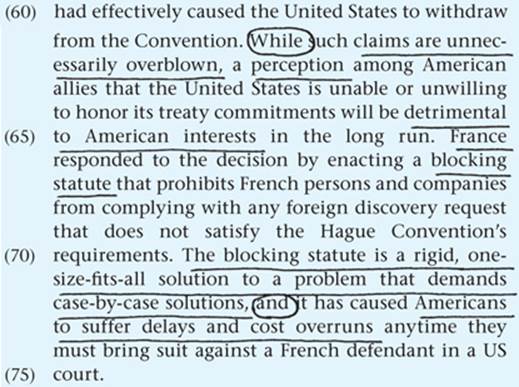

Read and annotate the passage that appears on the following page. Write down the summary you create in the blanks that appear at the end of the passage. Once you’re finished, compare your annotations and summary to the example on the following page.

SUMMARY

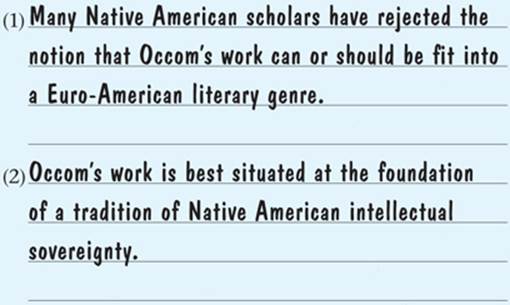

(1) ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

(2) ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

(3) ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

SUMMARY

Practice Question

Which of the following most accurately expresses the main point of the passage?

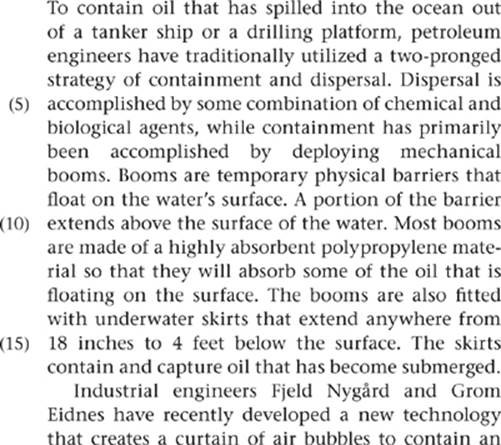

(A) Despite its limitations, the use of air-bubble curtains has proven to be more effective than any other method of containing oil spills.

(B) Two industrial chemists have made a valuable contribution to the field of petroleum engineering with their development of air-bubble curtains, a compressor-based technology for containing oceanic oil spills.

(C) The use of air-bubble curtains is a new method for containing oil spills that has distinct advantages over the use of mechanical booms.

(D) Mechanical booms, an unreliable method used to contain past oil spills, can finally be abandoned now that air-bubble-curtain technology has been developed.

(E) Most petroleum engineers today have rejected the use of mechanical booms and are embracing the use of air-bubble curtains as the most effective method for containing oil spills.

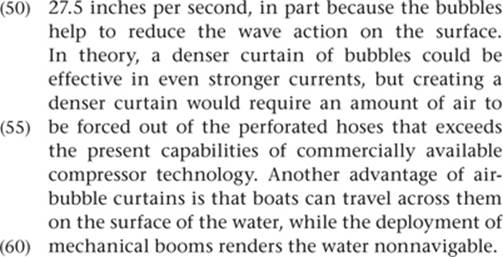

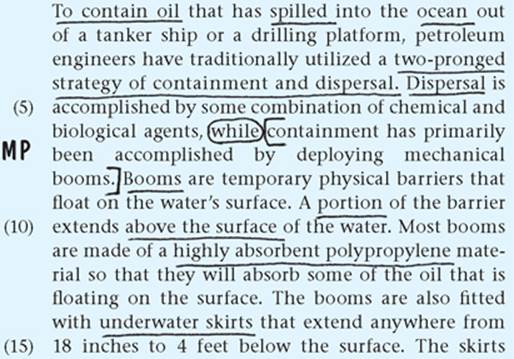

Answer and Analysis. The correct answer is choice C. Note how choice C tracks sentences two and three of the summary of the passage and quotes language from the topic sentence of the third paragraph. Even on Main Idea questions, the answer is in the passage; you just have to find it. Choice C doesn’t say much about paragraph one, but that’s OK; the purpose of paragraph one was to provide background information, so its content can be omitted from a statement of the passage’s main point. That’s the difference between a main point and a summary.

Choices A and E are wrong for the same reason: they go beyond the scope of the passage to compare air-bubble curtains to all other spill-containment technologies; the only other technology to which the passage compares air-bubble curtains is mechanical booms. Choice B accurately states the main point of paragraph two, but it omits any discussion of the opinion expressed in paragraph three. Finally, choice D takes the basic idea of the passage—which is that air-bubble curtains have some advantages over mechanical booms—and states it too strongly. Nowhere does the passage say that booms are “unreliable” or should “finally be abandoned.”

Variation: Primary Purpose Questions. Consider the following question:

The author’s main purpose in the passage is to

(A) defend a new technology against criticism

(B) identify the major shortcomings of the field of petroleum engineering and suggest how they should be remedied

(C) support the view that a new technology will actually be worse than the technology it was intended to replace

(D) show that the effectiveness of a new oil-spill-containment technology cannot be accurately gauged without further study

(E) explain the benefits of a new technology as compared to an existing technology

A question like this might also be worded to read, “Which one of the following most accurately states the primary function of the passage?”

These questions are just Main Idea questions that have been restated at one higher level of generality. Answering these questions requires you to (1) summarize the content of the passage; (2) describe that content in slightly more general terms; and (3) find the answer choice that matches your description. In comparing each answer choice to your description, you may find it helpful to draw on the technique you learned for answering Principle questions in Case 3 of Chapter 4: break each answer choice down into its constituent parts, and compare the parts to your description one at a time.

Here, we’ve already summarized the passage as part of the annotative-reading strategy. To restate that summary at one higher level of generality, you might say, “The passage describes an old technology, then it describes a new technology, and finally it explains two advantages that the new technology has over the old technology.” Now you can compare the answer choices to that description. You can eliminate choice A because the passage does not criticize the air-bubble-curtain technology. Choice B is too broad in scope; the passage is about two specific technologies, not the entire field of petroleum engineering. Choice C is wrong for the same reason choice A is wrong; the passage argues that air-bubble curtains may be superior to booms, not inferior. And choice D falls short because the passage does not call for further study. Choice E is the correct answer; it is a slightly less-thorough version of the description just articulated.

Case 4

Line ID Questions

This case addresses Line ID questions, which are questions that direct your attention to a particular line or lines in the passage. Over the past five years, there has been an average of about one Line ID question per passage. The skills you build in learning how to work these questions will also come in handy as you work the single most common type of question in the Reading Comprehension section, Information Retrieval questions, which are discussed in the next case.

STEP 1: Read the Question and Identify Your Task

Line ID questions require you either to determine the meaning of a word or phrase in context or to describe the purpose or function served by a particular portion of the text. The hallmark of these questions is that they include a parenthetical notation that tells you exactly what portion of the passage the question pertains to. Below are some examples of the more common wordings of Line ID questions (the blanks would be filled in with content from the passage, and the Xs and Ys would be replaced by numbers):

![]() In saying _________ (lines X–Y), the author most likely means which one of the following?

In saying _________ (lines X–Y), the author most likely means which one of the following?

![]() Which one of the following terms most accurately conveys the sense of the word “_______” as it is used in line X?

Which one of the following terms most accurately conveys the sense of the word “_______” as it is used in line X?

![]() The phrase “_______” (lines X–Y) is most likely intended by the author to mean:

The phrase “_______” (lines X–Y) is most likely intended by the author to mean:

![]() The author of the passage uses the term “______” (line X) primarily in order to:

The author of the passage uses the term “______” (line X) primarily in order to:

STEP 2: Go Back to the Passage and Find the Answer

Line ID questions make the process of going back to the passage easy. The question tells you where the relevant material appears; you don’t have to rely on your annotations to know where to go. But the portion of the passage that you reread should be broader than just the single line to which the question refers. Once you’ve located the word or phrase that’s the subject of the question, you should also read the sentence that immediately precedes it and the sentence that’s immediately after it. By reading these three sentences, you’ll get a fuller sense of the context in which the word is used.

Pay especially careful attention to the sentence that follows the word or phrase under review. Line ID questions frequently ask about terms of art or technical phrases about which the passage offers some explanation. That explanation is usually not offered until after the word has been introduced.

Some Line ID questions ask the author’s reason for using a particular term. Here, your annotations and your summary of the passage can help you get a handle on the function of a particular word or phrase. What is the main point of the paragraph in which the word or phrase appears? Did you circle any indicator words in the vicinity? The purpose for which a word or phrase is used depends heavily on the broader argumentative context.

STEP 3: Read Every Word of Every Answer Choice

Right answers to Line ID questions are wholly context-dependent. To make it easier to identify the right answer, you should come up with your own answer to the question before you leave the passage to start reviewing the answer choices. Generate a synonym or a definition to which you can compare each answer choice. This will help prevent you from losing your train of thought as you’re reviewing all five answer choices.

COMMON TYPES OF WRONG ANSWERS

1. A second meaning of the word. Many of the words and terms that appear in Line ID questions carry multiple meanings. Thus, it’s common for one of the wrong answer choices to list a meaning that can be correct but is inappropriate in context. For example, if the question asked about the word reflective and the passage used that word to mean “capable of reflecting light,” one of the answer choices would probably read “thoughtful or contemplative.” You can avoid these choices by reading the sentences immediately before and after the word or phrase in question so that you have a full sense of context.

2. An idea from a different portion of the passage. Many wrong answers to Line ID questions recite a phrase or concept that is drawn directly from a different portion of the passage. To a test taker who is relying solely on her recall of what she read, such choices can be tempting because they accurately restate something that the test taker remembers reading. Going back to the relevant portion of the passage will help you avoid falling for this type of wrong answer.

Practice

Read and annotate the passage that appears on the following page. Write down the summary you create in the blanks that appear at the end of the passage. Once you’re finished, compare your annotations and summary to the example that follows. Then work the two Line ID questions that appear on the page after the example annotation.

SUMMARY

(1) ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

(2) ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

(3) ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

(4) ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

SUMMARY

Practice Question 1

Which one of the following is closest to the meaning of the word “spurious” as used in line 40?

(A) inauthentic

(B) accidental

(C) alternative

(D) clandestine

(E) debatable

Answer and Analysis. Returning to the passage and reviewing the three sentences surrounding the word spurious in line 40 reveals that, in context, the passage is contrasting “spurious” trademarks with “genuine” trademarks. As the example of the deliberately misspelled “Louis Vuttion” label illustrates, you’re looking for an answer choice that captures the idea that a spurious trademark is a knockoff or an imposter. Therefore, the correct answer is choice A.

Practice Question 2

The passage discusses consumer confusion (lines 59–65) most likely in order to:

(A) explain the purpose for which trademark protection extends to a company’s trade dress

(B) support the claim that holdover trademark licensees are guilty of trademark counterfeiting

(C) call into question the assumption that a holdover licensee will profit from the goodwill associated with a trademark

(D) criticize large companies in the restaurant industry for failing to require franchisees to sign more restrictive franchise agreements

(E) provide an example of the ways in which trademarks make it easier for consumers to distinguish between different brands of goods

Answer and Analysis. The correct answer is choice B. This question illustrates the value of identifying the main point of each paragraph during your upfront reading of the passage. The summary identified the notion that holdover licensees are guilty of trademark counterfeiting as the main point of paragraph four, which is the paragraph in which lines 59–65 appear. Choice B directly connects the discussion of consumer confusion to paragraph four’s main point. Choices A and E each refer to topics that were discussed in the first paragraph, and they also add embellishments that go beyond the content of the passage. Choices C and D both misstate a topic that was discussed in paragraph two.

Case 5

Information Retrieval Questions

This case discusses Information Retrieval questions. Information Retrieval questions require you to select an answer choice that correctly restates one of the factual details presented in the passage. Over the past five years, this has been the single most common type of Reading Comprehension question; each passage has featured an average of between two and three Information Retrieval questions. That means that about 30 percent of the questions you answer will be Information Retrieval questions. Learning how to approach these questions is critical to your success on the Reading Comprehension section.

STEP 1: Read the Question and Identify Your Task

The test writers use a wide variety of wordings to ask Information Retrieval questions. The basic idea that the question will get across is, “What did the passage say about_______?” Some of the more common phrasings include:

![]() According to the passage, _______?

According to the passage, _______?

![]() The passage states (or “asserts,” “indicates,” “claims,” “mentions”) which one of the following about ______?

The passage states (or “asserts,” “indicates,” “claims,” “mentions”) which one of the following about ______?

![]() In the passage, the author makes which one of the following claims about _______?

In the passage, the author makes which one of the following claims about _______?

![]() Based on the passage, which one of the following is the author most likely to believe about _______?

Based on the passage, which one of the following is the author most likely to believe about _______?

![]() Given the information in the passage, _______?

Given the information in the passage, _______?

A few variations of this question type tend to be particularly time-consuming. For instance:

![]() The passage provides information sufficient to answer which one of the following questions?

The passage provides information sufficient to answer which one of the following questions?

![]() The information in the passage most strongly supports which one of the following statements?

The information in the passage most strongly supports which one of the following statements?

![]() According to the passage, each one of the following _______ EXCEPT:

According to the passage, each one of the following _______ EXCEPT:

The reason these variations are more time-consuming is that the question does not limit itself to a single topic. The topic varies from answer choice to answer choice, and typically the answer choices address five different topics, each of which was discussed at a different place in the passage.

STEP 2: Go Back to the Passage and Find the Answer

Your approach to Information Retrieval questions is substantively identical to the approach you took to answering Line ID questions: you’ll go back to the relevant portion of the passage, review what it says about the topic of the question, and then compare each answer choice to the passage. The primary difference between the two question types is that on Information Retrieval questions, it’s up to you to find the line or lines in the passage where the relevant information is located.

It’s on this front that annotative reading really pays dividends. By underlining key words as you read, you mapped the location of all of the facts, details, and examples discussed in the passage. Instead of having to reread the whole passage, you can scan through your annotations until you find an underlined word or phrase that is connected to the topic of the question. Your annotations will enable you to quickly locate the discussion of any given topic.

Once you’ve found the relevant portion of the passage, review what it says about the topic of the question. You’ll undertake this initial review at different times depending on the nature of the question. If the question limits itself to a particular topic, you should quickly review the relevant portion of the passage before you turn to the answer choices. But if you’re working one of the more time-consuming types of Information Retrieval question, where the topic at issue is determined solely by the content of the answer choices, your first rereading of the passage will not take place until after you’ve read the first answer choice.

Your rereading process will be iterative. In other words, you won’t just go back to the passage once. Instead, you’ll review the relevant portion of the passage multiple times as you work your way through the answer choices. After you read each answer choice, you’ll go back to the passage to see if the answer choice matches what was said in the passage. You’ll go back and forth between the passage and the answer choices multiple times.

Expediting the process of finding the relevant portion of the passage on Information Retrieval questions is the primary reason you underline the facts and details during your upfront reading. As you work the practice Reading Comprehension passages in this section, as well as the practice sections at the back of this book, make sure that your annotation system is serving the purpose of expediting your scan-and-retrieve process on Information Retrieval questions. It may take you some time before you can consistently recognize when a passage has moved onto a new topic, or determine how much of each topic you need to underline. Adjust your annotating process as you practice so that it serves its most important function: streamlining the process of going back to the passage on Information Retrieval questions.

STEP 3: Read Every Word of Every Answer Choice

The right answer to an Information Retrieval question will be drawn directly from the passage with no substantive modifications. But the answer is unlikely to be a direct quote from the passage. Instead, the test writers use synonyms and paraphrasing to make the right answer harder to recognize. For example, if the passage states that a technical breakthrough “will help overcome previous limitations on computing speed,” the answer might offer the paraphrase that the breakthrough “promises faster computing.”

COMMON TYPES OF WRONG ANSWERS

1. Introduces outside information on a related topic. Some wrong answers will introduce topics that are related to the topic of the passage but were not discussed in the passage. These answers are designed to take advantage of the fact that when you read, ordinarily you’re supposed to think about the broader implications of what you’ve read. Not so here. Anything from outside the passage is off-limits. For example, if the passage focused on a painting’s aesthetic value, an answer choice might ask you about its financial value. It doesn’t matter if an answer choice is true to the best of your knowledge. If it’s not explicitly stated in the passage, it can’t be the answer to an Information Retrieval question.

2. Directly contradicts information in the passage. There is usually at least one answer choice on each Information Retrieval question that states the exact opposite of something that was stated in the passage. Typically such a choice will include language that is quoted directly from the passage. These choices are designed to “sound right” to test takers who are relying on their recall of the passage. Going back to the passage to compare each answer choice to the content of the passage will enable you to easily recognize that these choices are incorrect.

3. In the right direction, but too strong. You’ve seen this category of wrong answer before, on Main Idea questions. Answer choices that take an idea from the passage and state a more extreme version of it are commonplace on Information Retrieval questions, too. If the passage points out two shortcomings of a proposal, a wrong answer might say that the proposal has no value. If the passage says that a solution is unlikely, a wrong answer might say that a solution is impossible. The right answer to an Information Retrieval question will mirror the passage’s content, tone, and precision.

4. Attributes an idea to the wrong person. In most Reading Comprehension passages, the author will not only state her own views but also recount and summarize the views of third parties. For instance: “Behavioral economists believe X. Classical economists believe Y. In my view, Z.” Wrong answers to Information Retrieval questions frequently attribute a view stated in the passage to the wrong person.

Practice

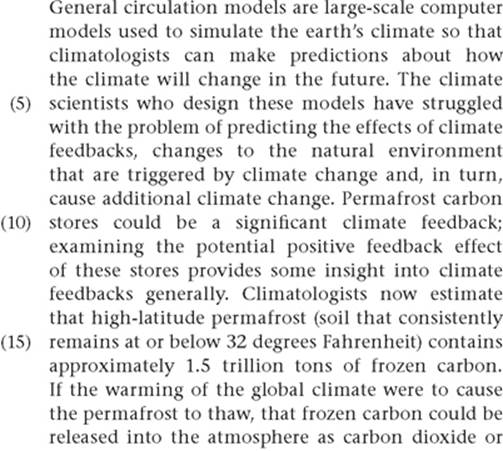

Read and annotate the passage that appears on the following page. Write down the summary you create in the blanks that appear at the end of the passage. Once you’re finished, compare your annotations and summary to the example that follows. Then work the two practice questions that appear on the following page.

SUMMARY

(1) ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

(2) ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

(3) ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

SUMMARY

Practice Question 1

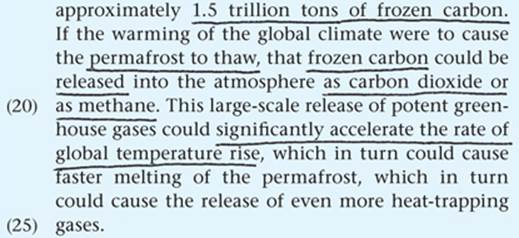

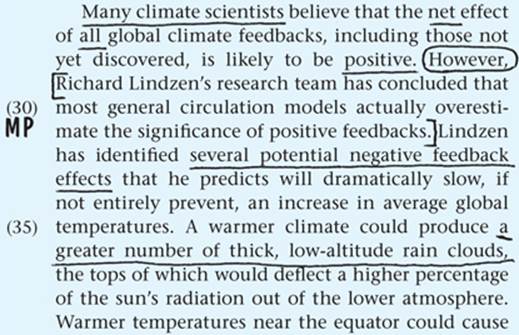

According to the passage, greenhouse gases released by the thawing of the permafrost

(A) both reflect heat back into space and also trap heat that has been emitted from the surface

(B) could cause global temperatures to increase at a substantially faster rate

(C) is one of the potentially significant negative climate feedbacks identified by Richard Lindzen’s research team

(D) would probably be in the form of methane rather than carbon dioxide

(E) could cause an increase in the frequency and severity of wildfires

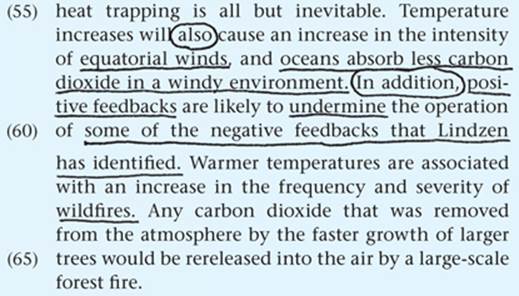

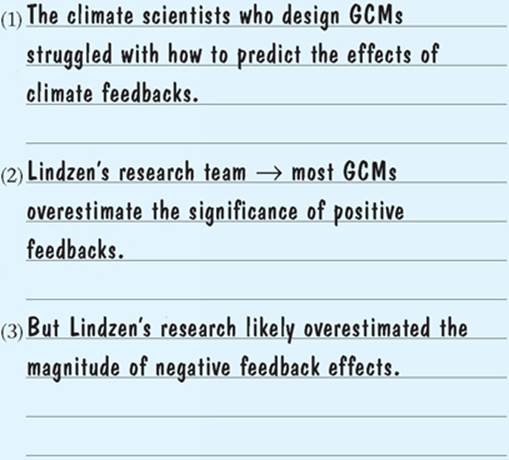

Answer and Analysis. The question asks about the thawing of the permafrost. The annotations show that this topic was discussed in the first paragraph. After quickly reviewing the discussion at lines 10–25, you turn to the answer choices. As for choice A, nothing in the first paragraph talks about the reflecting and trapping of heat; this choice is taken from the discussion of clouds at lines 51–55. Choice B looks good; it paraphrases the content contained in lines 17–23 of the passage. Choice C contradicts lines 11–12, which state that permafrost carbon stores are a potentialpositive feedback. Plus, the permafrost is not mentioned in paragraph two’s discussion of the findings made by Lindzen’s research team. Choice D is a distortion of the statement at lines 19–20 that carbon released by the thawing of the permafrost would be either in the form of carbon dioxide or methane. The passage does not take a position on which of those gases would be more prevalent. Choice E references the discussion of wildfires that appears at lines 63–66. The passage states that warmer temperatures could cause more frequent and severe wildfires, and the passage also states that the thawing of the permafrost could cause warmer temperatures. It might seem reasonable to connect those two ideas. But the passage itself never makes that connection. Choice B is closely and directly tethered to the passage’s content, so it is the correct answer.

Practice Question 2

The passage states that climate scientists:

(A) have concluded that most large-scale climate models overestimate the significance of positive feedbacks

(B) share the view that regulation is needed to slow the rate at which greenhouse gases are emitted into the atmosphere

(C) use the results of climate models to predict future changes to the earth’s climate

(D) have made no progress in their efforts to predict the effects of climate feedbacks

(E) generally believe that the net effect of all global climate feedbacks will be negative

Answer and Analysis. The correct answer is choice C, which restates the opening sentence of the passage (lines 1–4); its substitution of “climate scientists” for “climatologists” is supported by the sentence that begins on line 4. Choice A attributes an idea from the passage to the wrong person. This is an accurate statement of Richard Lindzen’s view (lines 28–31), but that view is in direct contrast to the view of “many climate scientists” expressed in lines 26–28. Choice B introduces new, outside information that is related to the topic of the passage. Choice B may well be a true statement, but since it’s not discussed anywhere in the passage it can’t be the correct answer. Choice D goes in the right direction, but it is too strong. Lines 5–6 say only that climate scientists have “struggled with” how to predict the effects of climate feedbacks; to say they “have made no progress” is an overstatement. Choice E directly contradicts the information in the passage. Lines 26–28 state that many climate scientists believe that the net effect of all global climate feedbacks is likely to be positive, not negative.

These two practice questions illustrate two fundamental points about Information Retrieval questions. First, it would be difficult to overstate the extent to which the correct answer must be drawn directly from the text of the passage. Before you select an answer, you should be able to point to the particular portion of the passage that makes the answer you’re picking the right answer. Second, the more thorough you are in comparing each answer choice to the passage, the better you will do on Information Retrieval questions. It’s the best way to ensure that you’re evaluating each answer with the necessary specificity and precision.

Case 6

Inference Questions

The focus of this case is Inference questions. On average, each passage in the Reading Comprehension section includes one Inference question. Don’t let the name mislead you; even on an Inference question, the right answer will be drawn directly from the passage. For that reason, Inference questions are very similar to Information Retrieval questions. You’ll utilize many of the same techniques you learned in the previous case to tackle Inference questions.

STEP 1: Read the Question and Identify Your Task

Below are some examples of typical Inference questions:

![]() Which one of the following inferences is most strongly supported by the passage?

Which one of the following inferences is most strongly supported by the passage?

![]() It can be inferred from the passage that which one of the following _______?

It can be inferred from the passage that which one of the following _______?

![]() It can be inferred from the passage that the author would be most likely to agree with which one of the following statements?

It can be inferred from the passage that the author would be most likely to agree with which one of the following statements?

![]() The passage most strongly suggests which one of the following about _______?

The passage most strongly suggests which one of the following about _______?

STEP 2: Go Back to the Passage and Find the Answer

The term inference carries a very particular meaning on the Reading Comprehension section. Ordinarily you think of inferences as conclusions that, while not definitively true, are very probably true based on a particular set of facts. For example, suppose that you walked into a room and saw that a fish tank had been overturned, there was water on the floor, no fish were anywhere in sight, and a cat was sitting next to the fish tank with water on its face licking its lips. You might infer that the cat knocked over the tank and then ate the fish. That conclusion is an example of what is normally meant by calling something an inference: a reasonable but probabilistic conclusion.

That meaning goes out the window on the Reading Comprehension section. Even though the question uses the term inference, the correct answer to the question will still be a statement that must be true based solely on the information in the passage. On the LSAT, if you were presented with the above set of facts, you could “infer” that any fish that were once in the tank are no longer in the tank, or that there is at least one animal in the room. Don’t read the term inference as an invitation to draw on outside knowledge of the topic or speculate about the significance of the content of the passage. Even on an Inference question, the answer is already there on the page; you just have to find it.

There are two main types of “inferences” you’ll be asked to draw in the Reading Comprehension section. The first one is a necessary-implication inference. For example, suppose that a passage argued that a poem written in 1820 was a particularly impressive artistic accomplishment because its originality of expression inaugurated a new rhyming technique that was previously unknown to nineteenth-century writers. Based on that argument, you could infer that the author of the passage believes that the historical circumstances surrounding the creation of a work of art are important in assessing its artistic value. The passage doesn’t come right out and say it, but based on what was said in the passage it necessarily must be true.

The second main type of inference you’ll be able to make is a detail-combination inference. For example, suppose that line 15 of the passage characterized a certain mathematician’s work as providing an exhaustive and comprehensive account of chaos theory. Suppose that line 37 of the same passage stated that the mathematician’s work did not include a discussion of Feigenbaum constants. You could combine these two statements to infer that Feigenbaum constants are not part of chaos theory. Where Information Retrieval questions required you to find the line on which one topic was discussed, detail-combination Inference questions require you to combine the lines on which two topics are discussed.

In the end, your approach to working Inference questions is virtually identical to your approach to working Information Retrieval questions. After reading each answer choice, you’ll reread the relevant portion (or portions) of the passage to see if the answer choice is either a combination of two statements from the passage or a necessary implication of something said in the passage. And you’ll go back to the passage multiple times, once for each answer choice.

STEP 3: Read Every Word of Every Answer Choice

As discussed above, the right answer will either be a combination of two details from the passage or a statement that is necessarily true based on a particular piece of information in the passage. With Inference questions, just as with Information Retrieval questions, the test writers are likely to disguise the correct answer by using synonyms and paraphrasing.

Common Types of Wrong Answers. The test writers use the same kinds of wrong answers on Inference questions that they use on Information Retrieval questions. So be on the lookout for answers that introduce outside information on a related topic, directly contradict information from the passage, are in the right direction but too strong, or attribute an idea to the wrong person.

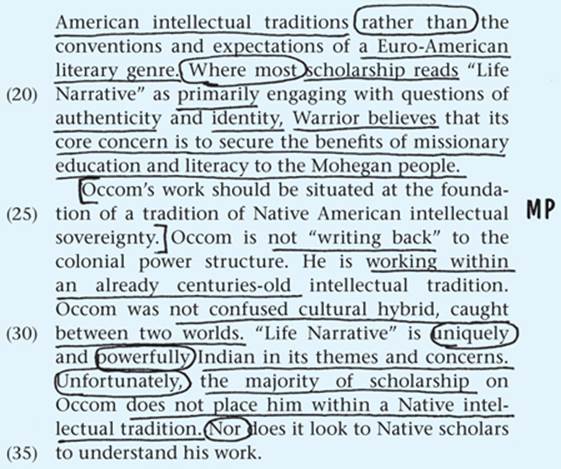

Practice

Read and annotate the passage that appears on the following page. Write down the summary you create in the blanks that appear at the end of the passage. Once you’re finished, compare your annotations and summary to the example that follows. Then work the practice question that appears on the following page.

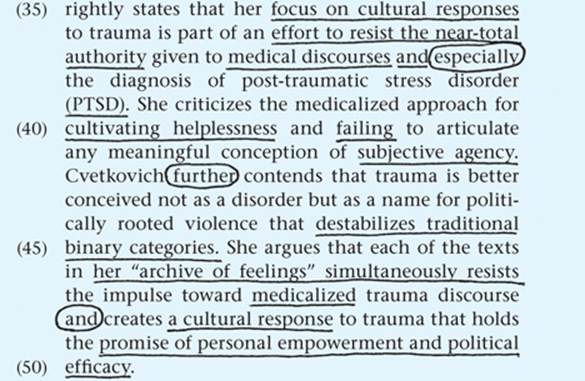

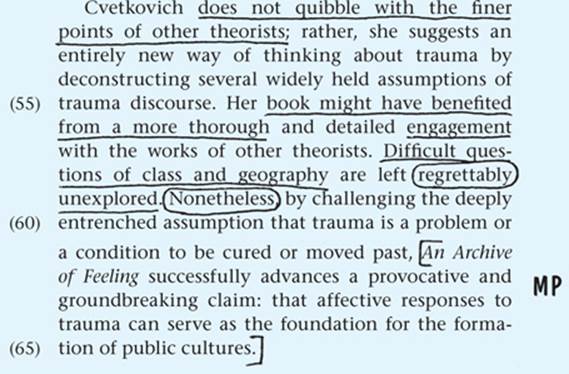

SUMMARY

(1) ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

(2) ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

(3) ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

SUMMARY

Practice Question

It can be inferred from the passage that Cvetkovich would be most likely to agree with which one of the following statements?

(A) The core principles of traditional trauma theory include the notion that trauma engenders public culture.

(B) The diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder has no role to play in trauma discourse.

(C) The idea that trauma is a productive force has been accepted by a majority of the field’s most well-established critics.

(D) Michelle Tea’s novels create a cultural response to trauma that has the potential to engender political efficacy.

(E) The investigative work of Margaret Randall exemplifies the dichotomous public–private approach to understanding trauma.

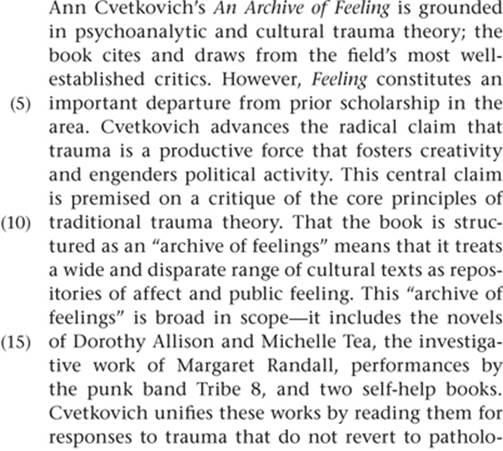

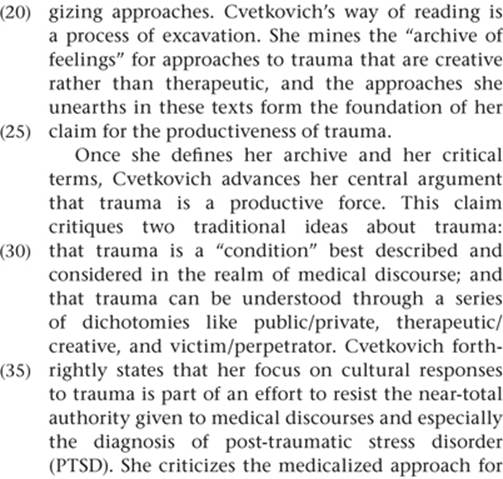

Answer and Analysis. The correct answer is choice D. This is a detail-combination inference. Lines 13–17 state that Tea’s novels are part of Cvetkovich’s “archive of feelings,” and lines 45–50 state that Cvetkovich believes that each of the texts in her “archive of feelings” holds the promise of political efficacy.

Choice A directly contradicts information from the passage: lines 4–10 and 59–65 establish that the notion that trauma engenders public culture is a radical departure from traditional trauma theory. Choice B is in the right direction, but it goes too far: lines 34–39 establish that Cvetkovich wants to “resist the near-total authority” given to the diagnosis of PTSD, but the passage does not go so far as to say that medical diagnosis should play no role whatsoever in trauma theory. Choice C goes beyond the scope of the passage. The passage discusses the content of Cvetkovich’s new theory, but it does not discuss that theory’s critical reception. Finally, choice E misstates the content of the passage. The passage draws no connection between its discussions of Randall’s investigative work (line 16) and the public–private dichotomy (line 33). If anything, the statement at lines 45–50 suggests that Cvetkovich’s view of the relationship between the two would be the opposite of what’s stated in choice E.

Case 7

Tone Questions

This case addresses Tone questions. Tone questions ask you to describe the author’s attitude toward a particular topic that is discussed in the passage. They will not ask you to describe the tone of the passage as a whole. Tone questions are not especially commonplace; there is an average of about one Tone question per Reading Comprehension section (that’s per section, not per passage).

STEP 1: Read the Question and Identify Your Task

You’ll know you’re dealing with a Tone question when you see any of the following question stems:

![]() The author’s attitude toward _______ is most accurately described as:

The author’s attitude toward _______ is most accurately described as:

![]() Which one of the following best characterizes the author’s attitude toward _______?

Which one of the following best characterizes the author’s attitude toward _______?

![]() The author’s stance toward _______ can best be described as:

The author’s stance toward _______ can best be described as:

![]() Which one of the following best describes the author’s opinion of _______?

Which one of the following best describes the author’s opinion of _______?

STEP 2: Go Back to the Passage and Find the Answer

Per usual, your first step in working a Tone question is to return to the portion of the passage that discusses the topic identified in the question. Use your underlining and annotation to quickly locate the topic. Reread the entirety of the pertinent portion of the passage. If the topic is discussed in more than one place in the passage, reread each of the discussions. As you read, try to come up with a rough formulation of the tone or attitude with which the author treats the topic.

On the LSAT, you can think about tone as having three component parts: valence, intensity, and content. Valence refers to the general direction or tenor of the author’s attitude. There are three basic tonal valences: positive, neutral, and negative. Intensity is a more specific description of the valence of the author’s attitude. If the tone is generally positive, how positive is it? A positive tone could be cautious, qualified, measured, enthusiastic, or unbridled, to name a few. Finally, content refers to the object or target of the author’s tone. This will be a specific, discrete aspect of the topic heading identified by the question.

STEP 3: Read Every Word of Every Answer Choice

The right answer to a Tone question will apply the same combination of valence and intensity that the passage did to the relevant content. Tone is similar to purpose in that it is a restatement or description of the passage’s content at a higher level of generality. As a result, you should treat Tone answer choices the same way you treat the answer choices to the Purpose questions discussed at the end of Case 3. Break them down into pieces. Each piece of the right answer will correspond to a specific piece of the passage.

COMMON TYPES OF WRONG ANSWERS

1. Wrong valence. Eliminating choices based on valence is the easiest way to narrow the field of answer choices. If the author’s attitude toward the topic in question is generally negative, any choice that is neutral or positive can be eliminated. Sometimes this technique will be enough to eliminate most of the wrong answers. But on more difficult Tone questions, four or even all five of the answer choices will correctly capture the tone’s valence.

2. Wrong intensity. Tone questions won’t require you to parse the fine-grained distinctions between, for example, a tone that is “persuasive” versus “satisfied” versus “assured.” The difference will be substantial, something like “unbridled” versus “qualified.” You can select between those answers based on whether the relevant text of the passage contains any caveats or notes of caution.

Practice

Read and annotate the passage that appears on the following page, summarizing the passage in the blanks at the end of the passage. Sample annotations and a sample summary follow, and a practice Tone question appears on the page following the annotated passage.

SUMMARY

(1) ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

(2) ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

(3) ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

(4) ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

SUMMARY

Practice Question

The author’s attitude toward the international reaction to the Supreme Court’s 1987 decision is most accurately described as

(A) disdain for the parochial interests that drove that reaction coupled with a dismissal of its significance

(B) acceptance of the policy reasons necessitating that reaction mitigated by a concern with the dangerous precedent it set

(C) anger over the unlawful nature of that reaction tempered by a grudging respect for the interests it advanced

(D) criticism of the force and nature of that reaction accompanied by an acknowledgment of its detrimental consequences to the United States

(E) approval of the decisive and forceful nature of that reaction tempered by a pessimistic outlook about the resolution of similar future disputes

Answer and Analysis. The correct answer is choice D. The best way to identify it as such is to break it into parts. The first portion of the answer, “criticism of the force and nature of that reaction,” corresponds to the “unnecessarily overblown” characterization in lines 62–63 and the “rigid, one-size-fits-all solution to a problem that demands case-by-case solutions” language in line 72. And the second portion of the answer, “acknowledgment of [the international reaction’s] detrimental consequences to the United States,” corresponds to the discussion of American interests at lines 61–65 and to the discussion of costs and delays at lines 72–75.

Each of the remaining choices has a valence problem. Choices B and E are both incorrect to say that the passage characterizes the international reaction in a generally positive manner. And choices A and C each misstate the passage’s attitude toward the consequences of this international reaction. The passage’s attitude is one of concern or dismay. That attitude is generally negative, not unconcerned or approving.

Case 8

Arguments-Style Questions

This case discusses a group of three different question types that give you new information and ask you to apply it to the passage in a specified manner.

The question might ask you to pick an answer choice that strengthens a portion of the passage, that weakens a portion of the passage, or that is most similar or closely analogous to a portion of the passage. The common thread between these question types is that you’ve seen them before in the Arguments section. You’ll use the same techniques you learned in Chapter 4 when you encounter Strengthen and Weaken questions in the Reading Comprehension section. This case briefly reviews those techniques. Parallel questions, on the other hand, require a slightly different approach in the Reading Comprehension section than in the Arguments section. This case introduces you to that approach.

STEP 1: Read the Question and Identify Your Task

Each passage will contain, on average, one Arguments-style question; the most common variation is a Parallel question. Following are some representative examples of how these questions will be worded. The language in these questions closely tracks the language used to ask the same kinds of questions in the Arguments section.

WEAKEN

![]() Which one of the following, if true, would most weaken the author’s argument as expressed in the passage?

Which one of the following, if true, would most weaken the author’s argument as expressed in the passage?

![]() Which one of the following, if true, would most weaken the position that the passage attributes to _______?

Which one of the following, if true, would most weaken the position that the passage attributes to _______?

![]() Which one of the following, if true, most seriously undermines the author’s claim that ________?

Which one of the following, if true, most seriously undermines the author’s claim that ________?

STRENGTHEN

![]() Which one of the following, if true, would most strengthen the contention in the passage that _______?

Which one of the following, if true, would most strengthen the contention in the passage that _______?

![]() Which one of the following, if true, would provide the most support for the ______ mentioned in lines X–Y?

Which one of the following, if true, would provide the most support for the ______ mentioned in lines X–Y?

PARALLEL

![]() As described in the passage, ______ is most closely analogous to which one of the following?

As described in the passage, ______ is most closely analogous to which one of the following?

![]() Suppose that ________ [a new factual scenario of some kind]. Which one of the following responses to that situation would be most consistent with the views expressed at lines X–Y of the passage?

Suppose that ________ [a new factual scenario of some kind]. Which one of the following responses to that situation would be most consistent with the views expressed at lines X–Y of the passage?

![]() As it is described in the passage, ______ would be best exemplified by which one of the following?

As it is described in the passage, ______ would be best exemplified by which one of the following?

![]() Which one of the following is most analogous to _______?

Which one of the following is most analogous to _______?

STEP 2: Go Back to the Passage and Find the Answer

By definition, these questions will give you new information to work with. So your task here is to find the pertinent information in the passage and then compare to it to the information in the question and answer choices. The nature of that comparison and how you’ll go about making it will depend on what type of question you’re working.

No matter what kind of comparison you’re asked to make, you should start by reviewing the portion of the passage from which the claim is taken. The question itself usually doesn’t recount all the relevant information from the passage. Use the same techniques you learned in Cases 4 and 5. Read the surrounding portions of the passage to get a sense of context, and use your summary of the passage to remind yourself of how the content of the question fits into the overall argument of the passage.

STEP 3: Read Every Word of Every Answer Choice

Your approach to Strengthen questions will mirror the approach you learned in Case 5 of the Arguments chapter. The question will present a claim (some kind of a statement of opinion) that’s taken from the passage. The claim will be phrased in general terms. The correct answer will provide a specific, concrete example that is consistent with that general claim. Common types of wrong answers include choices that weaken the claim, provide irrelevant information, make a general statement about a related topic, or offer support for a different but related claim.

Weaken questions, too, closely track their Arguments counterparts, which were discussed in Case 7 of Chapter 4. The question will present a broad-sweeping claim from the passage. The correct answer will either introduce new facts that are inconsistent with that claim or undermine the connection between the claim and any evidence offered in the passage to support it. Common types of wrong answers include choices that strengthen the claim, weaken a straw man, offer a generic background statement, or invite you to make an inference.

It’s only when you encounter a Parallel question that you’ll need to take a different approach. In the Arguments section, Parallel questions revolved around working with conditional statements. In the Reading Comprehension section, Parallel questions require you to take a general principle from the passage and apply it to a new situation. Sometimes the general principle will be explicitly stated in the passage. Other times you will have to extract or derive it by describing the relevant portion of the passage in general terms. Parallel questions typically involve (1) a particular person or type of person (or other actor) (2) taking an action, making a decision, or arriving at a judgment (3) for a specific reason or based on specific evidence.

Among the questions you worked in the Arguments section, it is Principle questions that are most similar to Parallel-style questions in the Reading Comprehension section. Finding the right answer to a Parallel question is a step-by-step process of breaking each answer choice down into pieces and matching each piece to the relevant portion of the passage. Work with the pieces of each answer choice one at a time. The actor, action, and reason all need to match. Here, as on Information Retrieval questions, you’ll go back and forth between the passage and the answer choices multiple times.

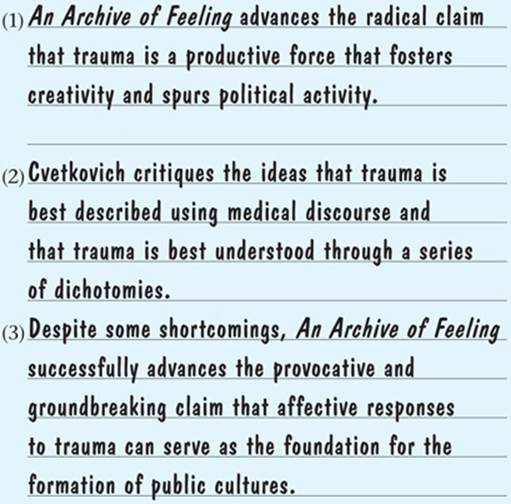

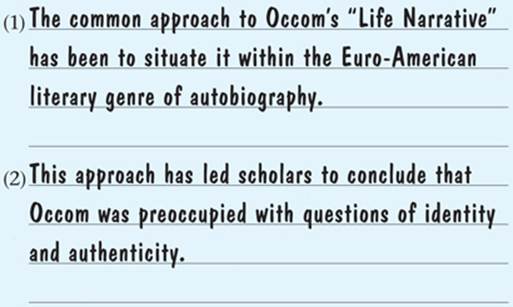

Practice

Read and annotate the passage that appears on the following page, summarizing the passage in the blanks at the end of the passage. Sample annotations and a sample summary follow. Two practice questions appear on the page following the annotated passage.

SUMMARY

(1) ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

(2) ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

(3) ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

(4) ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

SUMMARY

Practice Question 1

Which one of the following, if true, would most strengthen Longino’s contention that science chooses its areas of inquiry based on non-epistemic values?

(A) A public university issues a grant to an engineer’s proposed study of liquid coolants because the university believes the study has the potential to be quite lucrative.